Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Official Protest Thread...

- Thread starter Camille

- Start date

Directed by Frank E. Abney III and produced by Paige Johnstone, CANVAS tells the story of a Grandfather who, after suffering a devastating loss, is sent into a downward spiral and loses his inspiration to create. Years later, he decides to revisit the easel, and pick up the paint brush… but he can't do it alone.

@playahaitian

The black female guard who got punched by the white woman and defended herself

Hello. My name is Ashanti. I am a 28-year-old Black woman who lives in the DMV AREA. I recently was assaulted, attacked and harassed by a group of Trump supporters on Black Lives Matter Plaza in DC on January 5th, 2021. A video has surfaced where I was surrounded by a group of Trump extremists, and I honestly feared for my life. The video makes me look like I am the aggressor, but it does not show what happened prior to my defending myself. People shoved me, tried to take my phone and keys, yelled racial epithets at me, and tried to remove my mask. I asked them to social distance and stay out of my personal space due to COVID. They refused, and I was afraid of being hurt and harmed. After being assaulted, I defended myself. I am now facing criminal charges. I have also been relieved from my employment pending an investigation, which places me in a hardship. I am asking for support and help with funds for my legal fees and to maintain the essential things that I need to survive during this time. Any amount of help is truly appreciated.

Thank you in advance.

https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-ash...&utm_medium=copy_link_all&utm_source=customer

Hello. My name is Ashanti. I am a 28-year-old Black woman who lives in the DMV AREA. I recently was assaulted, attacked and harassed by a group of Trump supporters on Black Lives Matter Plaza in DC on January 5th, 2021. A video has surfaced where I was surrounded by a group of Trump extremists, and I honestly feared for my life. The video makes me look like I am the aggressor, but it does not show what happened prior to my defending myself. People shoved me, tried to take my phone and keys, yelled racial epithets at me, and tried to remove my mask. I asked them to social distance and stay out of my personal space due to COVID. They refused, and I was afraid of being hurt and harmed. After being assaulted, I defended myself. I am now facing criminal charges. I have also been relieved from my employment pending an investigation, which places me in a hardship. I am asking for support and help with funds for my legal fees and to maintain the essential things that I need to survive during this time. Any amount of help is truly appreciated.

Thank you in advance.

https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-ash...&utm_medium=copy_link_all&utm_source=customer

LDF Launches Groundbreaking Scholarship Fund and Pipeline Program to Create Next Generation of Civil Rights Attorneys to Dismantle Racial Injustice and Inequality in the South

Today, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) launched the groundbreaking Marshall-Motley Scholars Program (MMSP), an innovative educational and training opportunity that will produce the next generation of civil rights attorneys to serve Black communities in the South. As LDF...

Marshall-Motley Scholars Program

The Marshall-Motley Scholars Program is a groundbreaking commitment to endow the South with the next generation of civil rights lawyers.

This past Saturday, about a dozen people from across the United States and Canada held a Zoom memorial for a man whose remains have been lying in an unmarked grave in Nova Scotia since last spring.

He was Charles R. Saunders, and his lonely death in May belied his status as a foundational figure in a literary genre known as sword and soul. Some 40 years ago, Mr. Saunders reimagined the white worlds of Tarzan and Conan with Black heroes and African mythologies in books that spoke especially to Black fans eager for more fictional champions with whom they could identify.

Some of those on the Zoom call knew Mr. Saunders as a copy editor and writer for The Daily News of Halifax, a newspaper that went under in 2008. One first met him in the 1970s, when he was teaching at Algonquin College in Ontario. Most had been profoundly influenced by his fiction, especially his book series that features a warrior hero named Imaro, who battles enemies both human and supernatural and does it as part of a rich, vibrant Black civilization that contrasted sharply with the “Dark Continent” view of Africa that had long been served up by white writers.

All of them wanted, by the small gesture of the Zoom memorial and larger gestures yet to come, to make sure that Mr. Saunders’s death did not go unnoticed, and that his contributions do not go unremembered.

“Charles gave us that fictional hero that looked like us and existed in a world based on our origins,” Milton J. Davis, a Black writer of speculative fiction who acted as host of the Zoom memorial, said by email the next day. “He did it without using the ‘struggle’ narrative that traditional publishers seem to require from Black authors. Imaro’s struggles and triumphs were personal, not ‘racial,’ which for me was a breath of fresh air.”

Taaq Kirksey, another organizer of the memorial, first became enamored of Mr. Saunders’s fiction in 2004 while in his final semester at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and ever since he has been working to turn the Imaro stories into a movie or television series, an effort he said is close to bearing fruit.

Mr. Kirksey had corresponded with the reclusive Mr. Saunders on and off for years but had met him face to face only once, in June 2019, when he traveled to Nova Scotia and presented him with his first check from their long-simmering collaboration.

“I had always been afraid that his living situation was suboptimal,” Mr. Kirksey said, “and when I got up there to see him, those fears were validated.”

Mr. Saunders’s health was not good; he had diabetes, among other problems.

“My instinct told me he didn’t have much time,” Mr. Kirksey said.

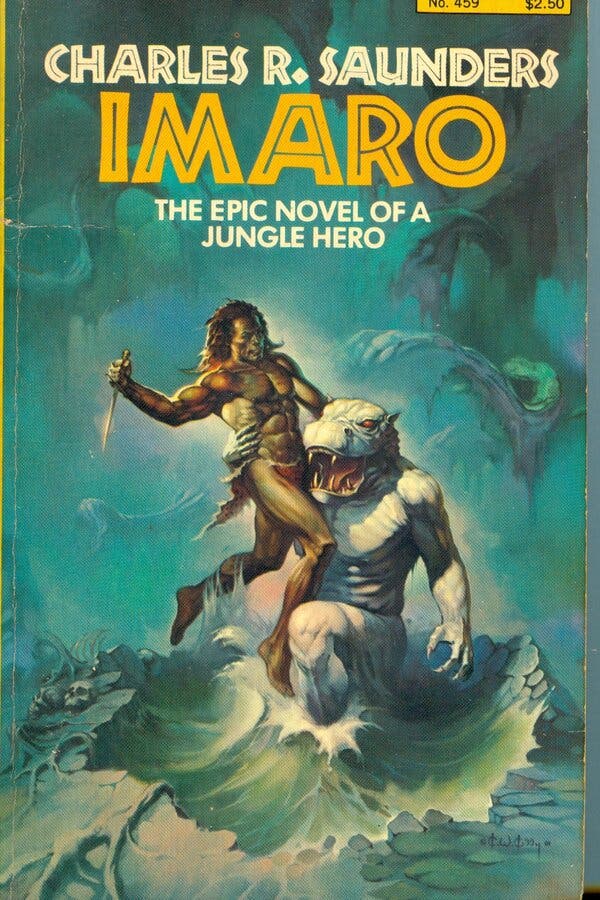

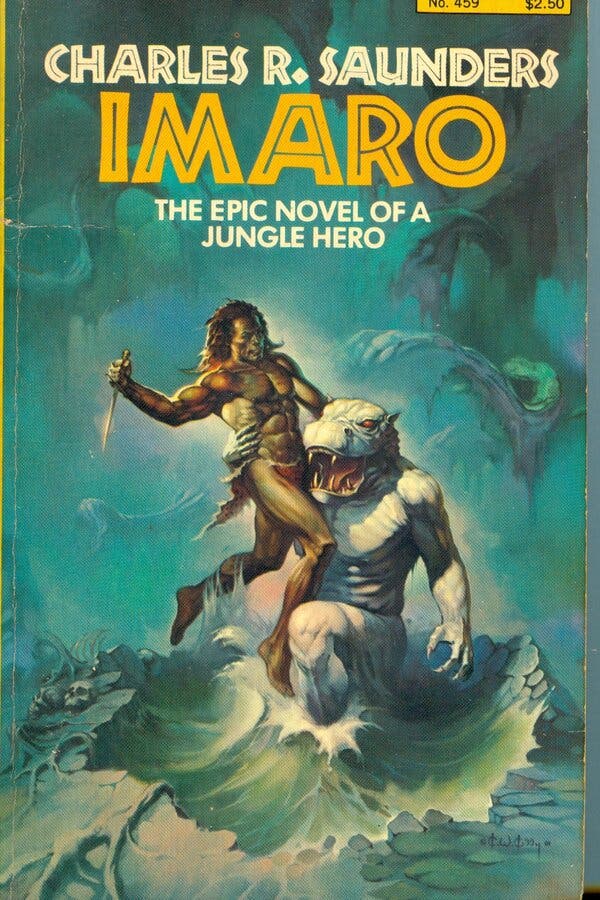

Image

Mr. Saunders began writing speculative fiction in the 1970s and published his first novel, “Imaro,” in 1981.Credit...via Taaq Kirksey

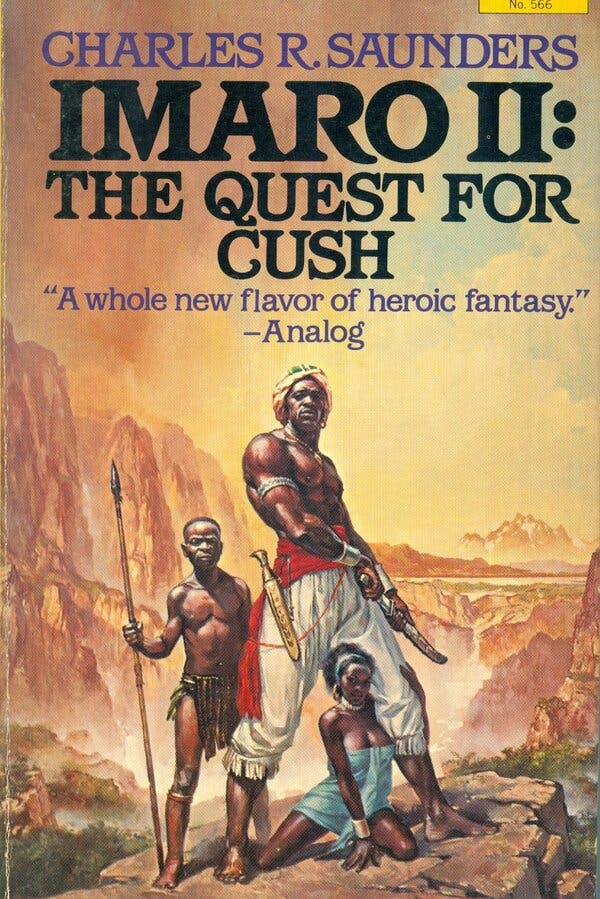

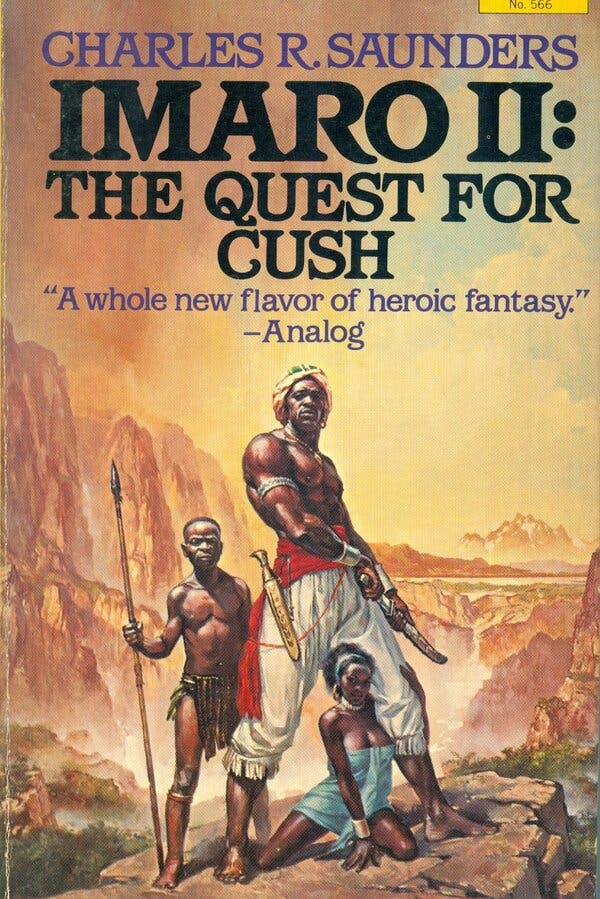

Image

“Imaro II: The Quest for Cush” was published in 1984. The Imaro books, Mr. Kirksey said, reclaimed a continent and a heritage for Black readers.Credit...via Taaq Kirksey

Mr. Saunders had no phone or internet service, and was in the habit of going to the local library once a week or so to keep up with friends by email. Early last year, when Covid-19 caused the province to lock down, his access to the library was cut off. Another long-distance friend, Dale Armelin, who lives in Colorado, became concerned when Mr. Saunders’s emails stopped. In early May he asked local officials to check on his friend at his apartment in the Dartmouth section of Halifax. He was fine.

But then, as Mr. Kirksey put it, “somewhere between May 2 and May 15, he wasn’t fine” — a crew doing work on Mr. Saunders’s apartment building found him dead. The cause wasn’t clear. He was 73.

Mr. Armelin eventually got a call from Nova Scotia officials, who told him that they had his name only because of his request for a wellness check. The officials could find no local friends or relatives. When a body goes unclaimed in the province, the office of the Public Trustee of Nova Scotia takes over. It arranged for Mr. Saunders to be buried on a hillside in Dartmouth Memorial Gardens.

Jon Tattrie, a journalist who had worked with Mr. Saunders for two years at The Daily News, pieced together what had happened in an article published by CBC News in September.

“By law,” he wrote, “the public purse covers the cost of the plot, and of the burial. But it doesn’t cover a headstone.”

And so Mr. Tattrie and others, including Mr. Kirksey and Mr. Davis, created a GoFundMe page to raise money for a headstone as well as a stone monument representing Imaro, Mr. Saunders’s best-known fictional creation. They will be installed in the next few months, Mr. Tattrie said during the Zoom memorial, and he hopes to organize a graveside service in May around the anniversary of the death.

It fell to Mr. Kirksey to put together a sparse biography of Mr. Saunders for the Zoom memorial.

Charles Robert Saunders was born on July 3, 1946, in Elizabeth, Pa., near Pittsburgh, and grew up there and in Norristown, Pa. In 1968 he earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology at Lincoln University, west of Philadelphia.

The next year, he moved to Canada to avoid the draft and became a teacher. At the Zoom memorial, Janet LeRoy recalled the first time she saw him, when she was a student at Carleton University in Ontario in the 1970s and glimpsed him through a doorway, talking to his students. His physical stature — he was 6-foot-4 or so — made a distinct impression, as did his Afro and dashiki top.

“He looked like he’d stepped off the TV show ‘The Mod Squad,’” she said.

Three years later, she finally met him when they were both teaching at Algonquin College. They became fast friends.

“He was a giant of a man, but he had such a tender, quiet voice,” she said. “We could talk about the deepest, darkest moments in our lives, and Charles would find a way to say something that would make us both chuckle.”

At some point Mr. Saunders moved to Nova Scotia, and in 1989 he began working at The Daily News, editing and sometimes writing, including about issues facing the Black community there.

“He was so quiet,” Mr. Tattrie, speaking at the Zoom memorial, recalled of his presence in the newsroom. “He would never draw attention to himself. But you noticed him. You could just tell there was a depth to him, a richness, that you don’t find in many other people.”

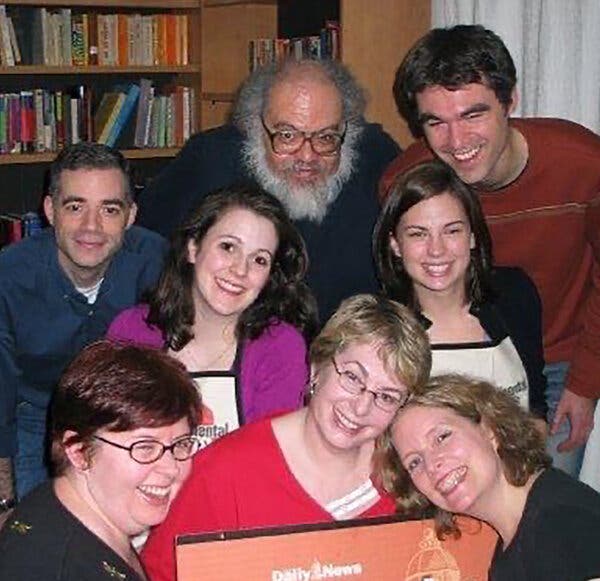

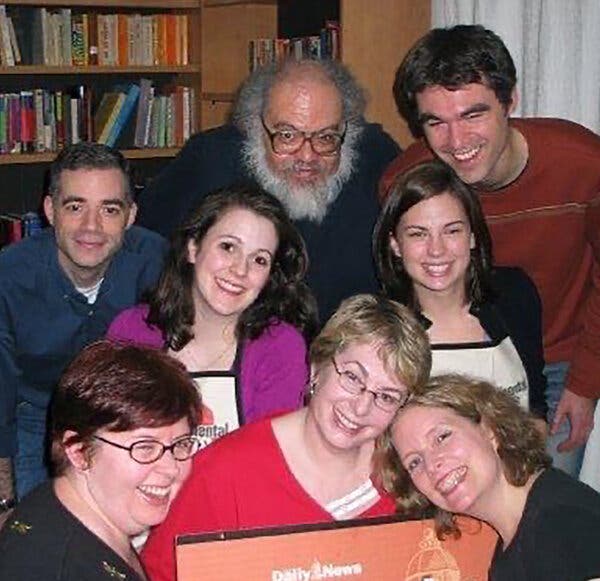

Mr. Saunders in 2008 with colleagues from the staff of The Daily News of Halifax, Nova Scotia, shortly after it shut down. He had been a copy editor and writer there since 1989.Credit...via Jon Tattrie

He was so good at not calling attention to himself that many at the newspaper didn’t realize that he had a whole other life as an author of speculative fiction, the umbrella genre that encompasses fantasy, science fiction and other strains of literature that deal in imagined worlds.

He had begun writing speculative fiction in the 1970s and published his first novel, “Imaro,” in 1981. As a child he had been enthralled by the fantasies spun by white writers like Robert E. Howard, who created Conan the Barbarian, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, who created Tarzan, the white African figure embodied most famously on the screen by Johnny Weissmuller. But he came to recognize the racism inherent in such works. Imaro was the result.

“I think he was born when I watched a Tarzan movie and fantasized a Black man jumping up and beating the hell out of Johnny Weissmuller,” Mr. Saunders told the journal Black American Literature Forum in 1984.

“Imaro II: The Quest for Cush” appeared in 1984, and “Imaro III: The Trail of Bohu” came out the next year. The books, Mr. Kirksey said, reclaimed a continent and a heritage for Black readers.

“For Tarzan to be the king of mythical Africa,” he said, “it’s an utter slap in the face to a young Black child who is looking for a place in his imagination where he can be indomitable, where he can be the king or the queen.”

Though Marvel Comics had introduced the character Black Panther and other Black heroes in its comics before Mr. Saunders’s “Imaro” books, only more recently have Black heroes and Black worlds become more common on bookshelves and on the big and small screens. The hit 2018 film “Black Panther” won three Oscars. Mr. Kirksey said that overdue progress rests in part on Mr. Saunders’s shoulders.

“It’s easy to look at the success of the movie ‘Black Panther’ and think that was always there,” he said. “That’s a very short memory speaking. Charles set that in motion in his own quiet way.”

Mr. Armelin said that though he had never met Mr. Saunders in person, “I consider him my best friend.” The two began corresponding in the mid-1970s, after Mr. Saunders had reached out when he saw a letter Mr. Armelin had written to Marvel commending the company for removing racist elements from a Conan tale it had republished.

During the Zoom memorial, Mr. Armelin confessed that, as a Black youth at an almost all-white Roman Catholic high school, he had “become an Uncle Tom.” Mr. Saunders, through his stories and his counsel, led him to embrace his heritage.

“What Charles did was, he gave me back my Blackness,” he said.

Mr. Kirksey said he believed that Mr. Saunders had married twice and that the marriages had ended in divorce. Whether he has any survivors remains unclear.

But his stories remain. Mr. Saunders created other fantasy worlds in books like “Abengoni,” published by Mr. Davis’s MVmedia in 2014. In the 1984 interview, he said that the possibilities for Imaro and the other characters who populated his imagination were endless.

“There is so much source material available on African culture and folklore,” he said, “that I would have to live indefinitely to do justice to it all.”

www.nytimes.com

www.nytimes.com

He was Charles R. Saunders, and his lonely death in May belied his status as a foundational figure in a literary genre known as sword and soul. Some 40 years ago, Mr. Saunders reimagined the white worlds of Tarzan and Conan with Black heroes and African mythologies in books that spoke especially to Black fans eager for more fictional champions with whom they could identify.

Some of those on the Zoom call knew Mr. Saunders as a copy editor and writer for The Daily News of Halifax, a newspaper that went under in 2008. One first met him in the 1970s, when he was teaching at Algonquin College in Ontario. Most had been profoundly influenced by his fiction, especially his book series that features a warrior hero named Imaro, who battles enemies both human and supernatural and does it as part of a rich, vibrant Black civilization that contrasted sharply with the “Dark Continent” view of Africa that had long been served up by white writers.

All of them wanted, by the small gesture of the Zoom memorial and larger gestures yet to come, to make sure that Mr. Saunders’s death did not go unnoticed, and that his contributions do not go unremembered.

“Charles gave us that fictional hero that looked like us and existed in a world based on our origins,” Milton J. Davis, a Black writer of speculative fiction who acted as host of the Zoom memorial, said by email the next day. “He did it without using the ‘struggle’ narrative that traditional publishers seem to require from Black authors. Imaro’s struggles and triumphs were personal, not ‘racial,’ which for me was a breath of fresh air.”

Taaq Kirksey, another organizer of the memorial, first became enamored of Mr. Saunders’s fiction in 2004 while in his final semester at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and ever since he has been working to turn the Imaro stories into a movie or television series, an effort he said is close to bearing fruit.

Mr. Kirksey had corresponded with the reclusive Mr. Saunders on and off for years but had met him face to face only once, in June 2019, when he traveled to Nova Scotia and presented him with his first check from their long-simmering collaboration.

“I had always been afraid that his living situation was suboptimal,” Mr. Kirksey said, “and when I got up there to see him, those fears were validated.”

Mr. Saunders’s health was not good; he had diabetes, among other problems.

“My instinct told me he didn’t have much time,” Mr. Kirksey said.

Image

Mr. Saunders began writing speculative fiction in the 1970s and published his first novel, “Imaro,” in 1981.Credit...via Taaq Kirksey

Image

“Imaro II: The Quest for Cush” was published in 1984. The Imaro books, Mr. Kirksey said, reclaimed a continent and a heritage for Black readers.Credit...via Taaq Kirksey

Mr. Saunders had no phone or internet service, and was in the habit of going to the local library once a week or so to keep up with friends by email. Early last year, when Covid-19 caused the province to lock down, his access to the library was cut off. Another long-distance friend, Dale Armelin, who lives in Colorado, became concerned when Mr. Saunders’s emails stopped. In early May he asked local officials to check on his friend at his apartment in the Dartmouth section of Halifax. He was fine.

But then, as Mr. Kirksey put it, “somewhere between May 2 and May 15, he wasn’t fine” — a crew doing work on Mr. Saunders’s apartment building found him dead. The cause wasn’t clear. He was 73.

Mr. Armelin eventually got a call from Nova Scotia officials, who told him that they had his name only because of his request for a wellness check. The officials could find no local friends or relatives. When a body goes unclaimed in the province, the office of the Public Trustee of Nova Scotia takes over. It arranged for Mr. Saunders to be buried on a hillside in Dartmouth Memorial Gardens.

Jon Tattrie, a journalist who had worked with Mr. Saunders for two years at The Daily News, pieced together what had happened in an article published by CBC News in September.

“By law,” he wrote, “the public purse covers the cost of the plot, and of the burial. But it doesn’t cover a headstone.”

And so Mr. Tattrie and others, including Mr. Kirksey and Mr. Davis, created a GoFundMe page to raise money for a headstone as well as a stone monument representing Imaro, Mr. Saunders’s best-known fictional creation. They will be installed in the next few months, Mr. Tattrie said during the Zoom memorial, and he hopes to organize a graveside service in May around the anniversary of the death.

It fell to Mr. Kirksey to put together a sparse biography of Mr. Saunders for the Zoom memorial.

Charles Robert Saunders was born on July 3, 1946, in Elizabeth, Pa., near Pittsburgh, and grew up there and in Norristown, Pa. In 1968 he earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology at Lincoln University, west of Philadelphia.

The next year, he moved to Canada to avoid the draft and became a teacher. At the Zoom memorial, Janet LeRoy recalled the first time she saw him, when she was a student at Carleton University in Ontario in the 1970s and glimpsed him through a doorway, talking to his students. His physical stature — he was 6-foot-4 or so — made a distinct impression, as did his Afro and dashiki top.

“He looked like he’d stepped off the TV show ‘The Mod Squad,’” she said.

Three years later, she finally met him when they were both teaching at Algonquin College. They became fast friends.

“He was a giant of a man, but he had such a tender, quiet voice,” she said. “We could talk about the deepest, darkest moments in our lives, and Charles would find a way to say something that would make us both chuckle.”

At some point Mr. Saunders moved to Nova Scotia, and in 1989 he began working at The Daily News, editing and sometimes writing, including about issues facing the Black community there.

“He was so quiet,” Mr. Tattrie, speaking at the Zoom memorial, recalled of his presence in the newsroom. “He would never draw attention to himself. But you noticed him. You could just tell there was a depth to him, a richness, that you don’t find in many other people.”

Mr. Saunders in 2008 with colleagues from the staff of The Daily News of Halifax, Nova Scotia, shortly after it shut down. He had been a copy editor and writer there since 1989.Credit...via Jon Tattrie

He was so good at not calling attention to himself that many at the newspaper didn’t realize that he had a whole other life as an author of speculative fiction, the umbrella genre that encompasses fantasy, science fiction and other strains of literature that deal in imagined worlds.

He had begun writing speculative fiction in the 1970s and published his first novel, “Imaro,” in 1981. As a child he had been enthralled by the fantasies spun by white writers like Robert E. Howard, who created Conan the Barbarian, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, who created Tarzan, the white African figure embodied most famously on the screen by Johnny Weissmuller. But he came to recognize the racism inherent in such works. Imaro was the result.

“I think he was born when I watched a Tarzan movie and fantasized a Black man jumping up and beating the hell out of Johnny Weissmuller,” Mr. Saunders told the journal Black American Literature Forum in 1984.

“Imaro II: The Quest for Cush” appeared in 1984, and “Imaro III: The Trail of Bohu” came out the next year. The books, Mr. Kirksey said, reclaimed a continent and a heritage for Black readers.

“For Tarzan to be the king of mythical Africa,” he said, “it’s an utter slap in the face to a young Black child who is looking for a place in his imagination where he can be indomitable, where he can be the king or the queen.”

Though Marvel Comics had introduced the character Black Panther and other Black heroes in its comics before Mr. Saunders’s “Imaro” books, only more recently have Black heroes and Black worlds become more common on bookshelves and on the big and small screens. The hit 2018 film “Black Panther” won three Oscars. Mr. Kirksey said that overdue progress rests in part on Mr. Saunders’s shoulders.

“It’s easy to look at the success of the movie ‘Black Panther’ and think that was always there,” he said. “That’s a very short memory speaking. Charles set that in motion in his own quiet way.”

Mr. Armelin said that though he had never met Mr. Saunders in person, “I consider him my best friend.” The two began corresponding in the mid-1970s, after Mr. Saunders had reached out when he saw a letter Mr. Armelin had written to Marvel commending the company for removing racist elements from a Conan tale it had republished.

During the Zoom memorial, Mr. Armelin confessed that, as a Black youth at an almost all-white Roman Catholic high school, he had “become an Uncle Tom.” Mr. Saunders, through his stories and his counsel, led him to embrace his heritage.

“What Charles did was, he gave me back my Blackness,” he said.

Mr. Kirksey said he believed that Mr. Saunders had married twice and that the marriages had ended in divorce. Whether he has any survivors remains unclear.

But his stories remain. Mr. Saunders created other fantasy worlds in books like “Abengoni,” published by Mr. Davis’s MVmedia in 2014. In the 1984 interview, he said that the possibilities for Imaro and the other characters who populated his imagination were endless.

“There is so much source material available on African culture and folklore,” he said, “that I would have to live indefinitely to do justice to it all.”

A Black Literary Trailblazer’s Solitary Death: Charles Saunders, 73 (Published 2021)

His speculative fiction was built on Black heroes and African themes. He died alone and unrecognized, but friends are trying to make amends.

The Difference Between First-Degree Racism and Third-Degree Racism

Only when people align on what racist behavior looks like will we be able to take practical steps to make those behaviors costly.

The unrelenting protests, the supportive statements from white leaders nationwide, and the early momentum behind policing policy changes are all indications that this might be a turning point in our nation’s battle against racism. Will we seize this opportunity or will we lose momentum, showing once again that America can be “a 10-day nation” that moves on too easily to the next crisis, as Martin Luther King Jr. warned a fellow civil-rights activist in 1963?

My father, Emmett Rice, and I had hundreds of conversations about race and racism from the time I was a boy until a few weeks before he died, in 2011, at 91 years old. He was the most intellectually curious person I have ever known. He grew up in South Carolina in the Jim Crow era of the 1920s and ’30s. Despite losing his father when he was only 7, he graduated from college, served in World War II with the Tuskegee Airmen, earned a doctorate in economics, and became one of the seven governors of the Federal Reserve Board in the 1980s. Racism still chased him and burdened him every day of his life. So he armed me with the knowledge he’d amassed, in hopes I could do even more.

www.linkedin.com

www.linkedin.com

www.theatlantic.com

www.theatlantic.com

Only when people align on what racist behavior looks like will we be able to take practical steps to make those behaviors costly.

The unrelenting protests, the supportive statements from white leaders nationwide, and the early momentum behind policing policy changes are all indications that this might be a turning point in our nation’s battle against racism. Will we seize this opportunity or will we lose momentum, showing once again that America can be “a 10-day nation” that moves on too easily to the next crisis, as Martin Luther King Jr. warned a fellow civil-rights activist in 1963?

My father, Emmett Rice, and I had hundreds of conversations about race and racism from the time I was a boy until a few weeks before he died, in 2011, at 91 years old. He was the most intellectually curious person I have ever known. He grew up in South Carolina in the Jim Crow era of the 1920s and ’30s. Despite losing his father when he was only 7, he graduated from college, served in World War II with the Tuskegee Airmen, earned a doctorate in economics, and became one of the seven governors of the Federal Reserve Board in the 1980s. Racism still chased him and burdened him every day of his life. So he armed me with the knowledge he’d amassed, in hopes I could do even more.

Thirty years ago, my dad gave me his playbook to put racism to rest, and it inspired me to dedicate my career to executing his vision. Dad’s playbook included one insight that all Americans should hear, at least those who hope that when it comes to addressing racism, we can do better. As an economist, he told me that we have to “increase the cost of racist behavior.” Doing so, he said, would create the conditions for black people to harness the economic power essential to changing the narrative in white America’s mind about race.

We can ratchet up that cost in several ways, starting today. The first step is to clarify what constitutes racist behavior. Defining it makes denying it or calling it something else that much harder. There are few things that white Americans fear more than being exposed as racist, especially when their white peers can’t afford to come to their defense. To be outed as a racist is to be convicted of America’s highest moral crime. Once we align on what racist behavior looks like, we can make those behaviors costly.

The most well-understood dimension involves taking actions that people of color view as overtly prejudiced—policing black citizens much differently than whites, calling the police on a black bird-watcher in Central Park who is asking you to obey the law, calling somebody the N-word to show them who is boss. This is racism in the first degree. If officers anticipated that they would be held fully accountable for bad policing, they would do more good policing and we could begin healing the wounds they’ve inflicted on black people for centuries.

Then there is opposing or turning one’s back on anti-racism efforts, often justified by the demonization of the people courageously tackling racist behavior. I call this racism in the second degree, akin to aiding and abetting. George Floyd’s death under yet another police officer’s knee exposed the NFL’s four-year effort to avoid confronting racist policing by way of demonizing Colin Kaepernick. When the NFL’s sponsors could no longer stay silent and its star players (both black and white) spoke out, the costs were so high that the commissioner felt compelled to apologize—though notably not to Kaepernick himself.

The final, most pernicious category undergirds the everyday black experience. When employers, educational institutions, and governmental entities do not unwind practices that disadvantage people of color in the competition with whites for economic and career mobility, that is fundamentally racist—not to mention cancerous to our economy and inconsistent with the American dream. For example, the majority of white executives operate as if there is a tension between increasing racial diversity and maintaining the excellence-based “meritocracies” that have made their organizations successful. After all, who in their right mind would argue against the concept of meritocracy?

When these executives are challenged on hiring practices, their first excuse is always “The pipeline of qualified candidates is too small, so we can only do so much right now.” Over the past 20 years, I have not once heard an executive follow up the “pipeline is too small” defense with a quantitative analysis of that pipeline. This argument is lazy and inaccurate, and it attempts to shift the responsibility to fix an institution’s problem onto black people and the organizations working to advance people of color. When asked why they have so few minorities in senior leadership roles, executives’ most common response is “There are challenges with performance and retention.” To reinforce their meritocracy narrative, white leaders point to the few black people they know who have made it to the top, concluding inaccurately that they were smarter and worked harder than the rest.

Organizations cannot be meritocracies if their small number of black employees spend a third of their mental bandwidth in every meeting of every day distracted by questions of race and outcomes. Why are there not more people like me? Am I being treated differently? Do my white colleagues view me as less capable? Am I actually less capable? Will my mistakes reflect negatively on other black people in my firm? These questions detract from our energy to compete for promotions with white peers who have never spent a moment distracted in this way. I wager that 90 percent of the white executives who read these last sentences are now asking, particularly after recent events, “How did we miss that?” This dimension of racism is particularly hard to root out, because many of our most enlightened white leaders do not even realize what they are doing. This is racism in the third degree, akin to involuntary manslaughter: We are not trying to hurt anyone, but we create the conditions that shatter somebody else’s future aspirations. Eliminating third-degree racism is the catalyst to expanding economic power for people of color, so it merits focus at the most senior levels of education, government, and business.

Employers whose efforts to increase diversity lack the same analytical and executional rigor that is taken for granted in every other part of their business engage in practices that disadvantage black people in the competition for economic opportunity. By default, this behavior protects white people’s positions of power. The nonprofit organization that I have built over the past 20 years, Management Leadership for Tomorrow, has advanced more than 8,000 students and professionals of color toward leadership positions, and we partner with more than 120 of the most aspirational employers to support their diversity strategy, as well as their recruiting and advancement efforts. Yet I have not seen 10 diversity plans that have the foundational elements that organizations require everywhere else: a fact-based diagnosis of the underlying problems, quantifiable goals, prioritized areas for investment, interim progress metrics, and clear accountability for execution. Expanding diversity is not what compromises excellence; instead, it is our current approach to diversity that compromises excellence and becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

We can increase the cost of this behavior by calling on major employers to sign on to basic practices that demonstrate that black lives matter to them. These include: (1) acknowledging what constitutes third-degree racism so there is no hiding behind a lack of understanding or fuzzy math, (2) committing to developing and executing diversity plans that meet a carefully considered and externally defined standard of rigor, and (3) delivering outcomes in which the people of color have the same opportunities to advance.

Companies that sign on will be recognized and celebrated. Senior management teams that decline to take these basic steps will no longer be able to hide, and they will struggle to recruit and retain top talent of all colors who will prefer firms that have signed on. The economic and reputational costs will increase enough for behavior and rhetoric to change. Then more people of color will become economically mobile, organizations will become more diverse and competitive, and there will be a critical mass of black leaders whose institutional influence leads to more racially equitable behavior. These leaders will also have the economic power to further elevate the cost of all other types of racist behavior, in policing, criminal justice, housing, K–12 education, and health care—systems that for decades have been putting knees on the necks of our most vulnerable citizens and communities.

Third-degree racism can be deadly. For at least the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mandated that in order to get tested, you had to go to a primary-care doctor to get a prescription and then, in some areas, also get a referral to a specialist who could approve a test, because they were in limited supply. That process made it much harder for minorities to access tests, because they are much less likely to have primary-care physicians. This is one of several reasons the hospitalization and death rates for minorities are disproportionately higher than those for whites. If the people who designed that process knew up front that they would be exposed as racist, fired, and ostracized if their approach put minorities at a greater health risk than white people, they would have designed it differently and saved black lives. Just having a critical mass of minorities in decision-making roles regarding that test-qualification process would have also saved many lives.

Rooting out third-degree racism is what will ultimately change the narrative about race. When white people see more black people on the same path as they are, when white people are working in diverse organizations, and when they are proximate to black leaders beyond athletes and entertainers, only then will they stop fearing and feeling superior to the black people they don’t know.

This is the path that will finally lift racism’s enormous burden off the backs of black people—the burden that my dad spent his nine decades working to shed, and that he hoped to avoid passing down to me, and that I am trying not to pass down to my 18-year old son as he graduates from high school and moves away. But if I am fortunate enough to someday have a grandson, and if he can grow up in a world where he can dedicate his full energy to becoming the best American he can be—as white people have been doing for 400 years—then my dad, so many other black fathers, and maybe even George Floyd will be able to rest in peace.

We can ratchet up that cost in several ways, starting today. The first step is to clarify what constitutes racist behavior. Defining it makes denying it or calling it something else that much harder. There are few things that white Americans fear more than being exposed as racist, especially when their white peers can’t afford to come to their defense. To be outed as a racist is to be convicted of America’s highest moral crime. Once we align on what racist behavior looks like, we can make those behaviors costly.

The most well-understood dimension involves taking actions that people of color view as overtly prejudiced—policing black citizens much differently than whites, calling the police on a black bird-watcher in Central Park who is asking you to obey the law, calling somebody the N-word to show them who is boss. This is racism in the first degree. If officers anticipated that they would be held fully accountable for bad policing, they would do more good policing and we could begin healing the wounds they’ve inflicted on black people for centuries.

Then there is opposing or turning one’s back on anti-racism efforts, often justified by the demonization of the people courageously tackling racist behavior. I call this racism in the second degree, akin to aiding and abetting. George Floyd’s death under yet another police officer’s knee exposed the NFL’s four-year effort to avoid confronting racist policing by way of demonizing Colin Kaepernick. When the NFL’s sponsors could no longer stay silent and its star players (both black and white) spoke out, the costs were so high that the commissioner felt compelled to apologize—though notably not to Kaepernick himself.

The final, most pernicious category undergirds the everyday black experience. When employers, educational institutions, and governmental entities do not unwind practices that disadvantage people of color in the competition with whites for economic and career mobility, that is fundamentally racist—not to mention cancerous to our economy and inconsistent with the American dream. For example, the majority of white executives operate as if there is a tension between increasing racial diversity and maintaining the excellence-based “meritocracies” that have made their organizations successful. After all, who in their right mind would argue against the concept of meritocracy?

When these executives are challenged on hiring practices, their first excuse is always “The pipeline of qualified candidates is too small, so we can only do so much right now.” Over the past 20 years, I have not once heard an executive follow up the “pipeline is too small” defense with a quantitative analysis of that pipeline. This argument is lazy and inaccurate, and it attempts to shift the responsibility to fix an institution’s problem onto black people and the organizations working to advance people of color. When asked why they have so few minorities in senior leadership roles, executives’ most common response is “There are challenges with performance and retention.” To reinforce their meritocracy narrative, white leaders point to the few black people they know who have made it to the top, concluding inaccurately that they were smarter and worked harder than the rest.

Organizations cannot be meritocracies if their small number of black employees spend a third of their mental bandwidth in every meeting of every day distracted by questions of race and outcomes. Why are there not more people like me? Am I being treated differently? Do my white colleagues view me as less capable? Am I actually less capable? Will my mistakes reflect negatively on other black people in my firm? These questions detract from our energy to compete for promotions with white peers who have never spent a moment distracted in this way. I wager that 90 percent of the white executives who read these last sentences are now asking, particularly after recent events, “How did we miss that?” This dimension of racism is particularly hard to root out, because many of our most enlightened white leaders do not even realize what they are doing. This is racism in the third degree, akin to involuntary manslaughter: We are not trying to hurt anyone, but we create the conditions that shatter somebody else’s future aspirations. Eliminating third-degree racism is the catalyst to expanding economic power for people of color, so it merits focus at the most senior levels of education, government, and business.

Employers whose efforts to increase diversity lack the same analytical and executional rigor that is taken for granted in every other part of their business engage in practices that disadvantage black people in the competition for economic opportunity. By default, this behavior protects white people’s positions of power. The nonprofit organization that I have built over the past 20 years, Management Leadership for Tomorrow, has advanced more than 8,000 students and professionals of color toward leadership positions, and we partner with more than 120 of the most aspirational employers to support their diversity strategy, as well as their recruiting and advancement efforts. Yet I have not seen 10 diversity plans that have the foundational elements that organizations require everywhere else: a fact-based diagnosis of the underlying problems, quantifiable goals, prioritized areas for investment, interim progress metrics, and clear accountability for execution. Expanding diversity is not what compromises excellence; instead, it is our current approach to diversity that compromises excellence and becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

We can increase the cost of this behavior by calling on major employers to sign on to basic practices that demonstrate that black lives matter to them. These include: (1) acknowledging what constitutes third-degree racism so there is no hiding behind a lack of understanding or fuzzy math, (2) committing to developing and executing diversity plans that meet a carefully considered and externally defined standard of rigor, and (3) delivering outcomes in which the people of color have the same opportunities to advance.

Companies that sign on will be recognized and celebrated. Senior management teams that decline to take these basic steps will no longer be able to hide, and they will struggle to recruit and retain top talent of all colors who will prefer firms that have signed on. The economic and reputational costs will increase enough for behavior and rhetoric to change. Then more people of color will become economically mobile, organizations will become more diverse and competitive, and there will be a critical mass of black leaders whose institutional influence leads to more racially equitable behavior. These leaders will also have the economic power to further elevate the cost of all other types of racist behavior, in policing, criminal justice, housing, K–12 education, and health care—systems that for decades have been putting knees on the necks of our most vulnerable citizens and communities.

Third-degree racism can be deadly. For at least the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mandated that in order to get tested, you had to go to a primary-care doctor to get a prescription and then, in some areas, also get a referral to a specialist who could approve a test, because they were in limited supply. That process made it much harder for minorities to access tests, because they are much less likely to have primary-care physicians. This is one of several reasons the hospitalization and death rates for minorities are disproportionately higher than those for whites. If the people who designed that process knew up front that they would be exposed as racist, fired, and ostracized if their approach put minorities at a greater health risk than white people, they would have designed it differently and saved black lives. Just having a critical mass of minorities in decision-making roles regarding that test-qualification process would have also saved many lives.

Rooting out third-degree racism is what will ultimately change the narrative about race. When white people see more black people on the same path as they are, when white people are working in diverse organizations, and when they are proximate to black leaders beyond athletes and entertainers, only then will they stop fearing and feeling superior to the black people they don’t know.

This is the path that will finally lift racism’s enormous burden off the backs of black people—the burden that my dad spent his nine decades working to shed, and that he hoped to avoid passing down to me, and that I am trying not to pass down to my 18-year old son as he graduates from high school and moves away. But if I am fortunate enough to someday have a grandson, and if he can grow up in a world where he can dedicate his full energy to becoming the best American he can be—as white people have been doing for 400 years—then my dad, so many other black fathers, and maybe even George Floyd will be able to rest in peace.

The Difference Between First-Degree Racism and Third-Degree Racism

This summer, we witnessed a new chapter in our nation’s fight against racism, as citizens marched together in protest against multiple extrajudicial killings of Black Americans. It was an “aha” moment felt across the country, and around the world.

The Difference Between First-Degree Racism and Third-Degree Racism

Only when people align on what racist behavior looks like will we be able to take practical steps to make those behaviors costly.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 105

- Views

- 7K

- Replies

- 58

- Views

- 866

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 116