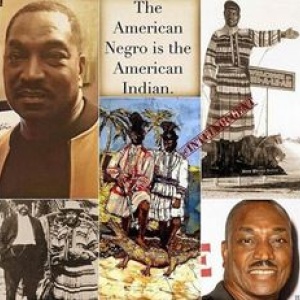

White Immigrants ($5 Indians) Stole Money And Land From Indigenous Aboriginals Now Owed To Their Descendants Called “African-Americans”

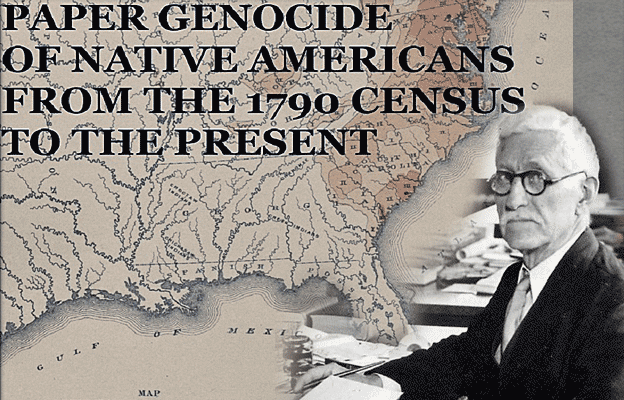

The actual Indians, or rather known as the American Aborigines, have since blamed the government for the mismanagement of a trust in their names, for well over 120 years, and now the US Goverment owes them tens of billions of dollars.

The dispute dates back to 1887, when Congress made the Interior Department the trustee for approximately 145 million acres of Indian lands in America.

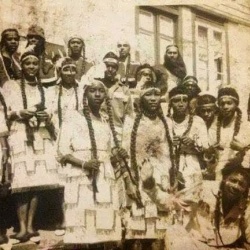

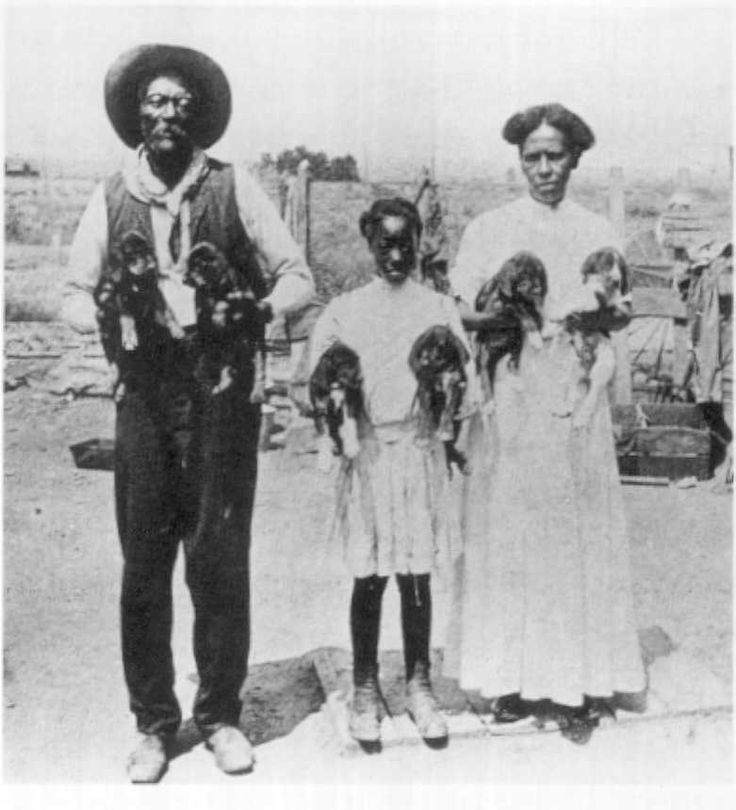

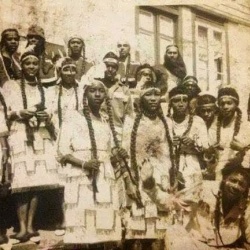

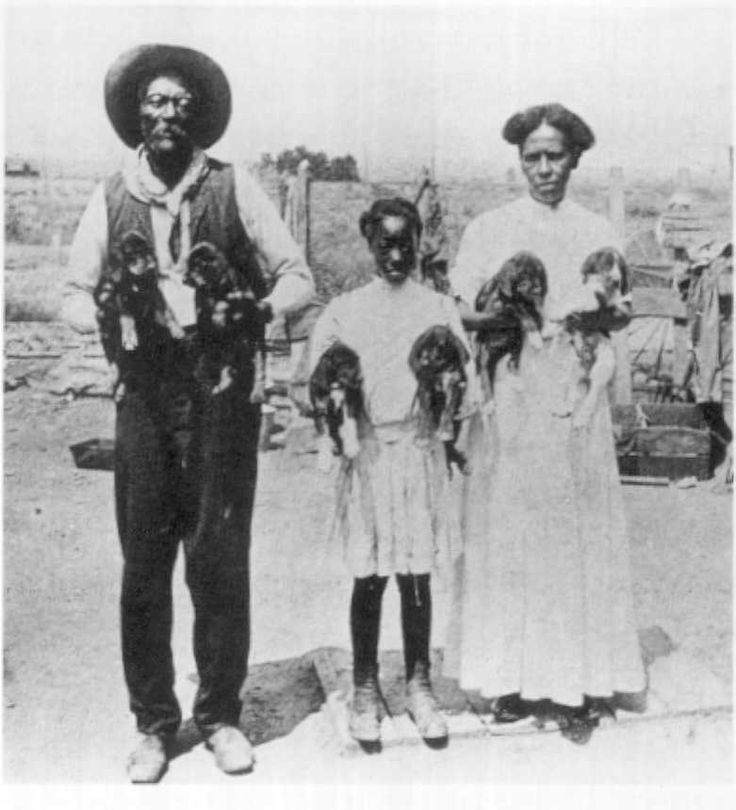

Black Indians, or rather Aborigines of America, were supposed to benefit but the government gave the majority of the land, legal tenders, tax reliefs and other federal specialized benefits to white settlers; who paid-off the citizenship administrative organizations, in order to become members of what is known as the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory by Congress.

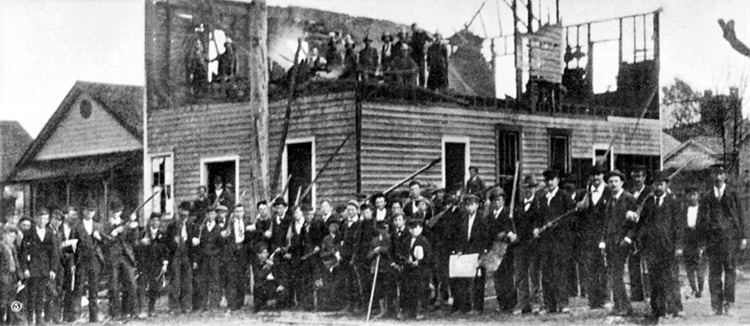

White settlers sought to reap the benefits of the Aborigines. In fact, one example of that would be the complexity of how successful, but so openly fraudulent they did it.

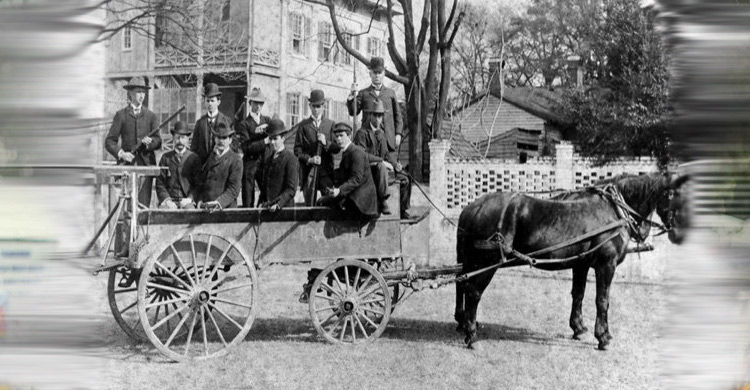

In 1895, the white settlers were informed of what benefits the Indians were entitled to, so they traveled to the Dawes Roll Commission to inquire about having their names enlisted on the roll cards for full blooded and/or Freedman Indians of America lands.

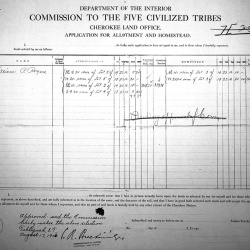

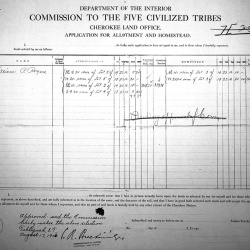

In 1898, the Dawes Roll acted as a census responsible for documenting records of one’s ethnic backgrounds, in order to determine one’s association with specific American Indian tribes.

Also, it played an important role with determining which Indian tribes would get land allotments and other benefits that I detailed earlier, in return for abolishing their tribal governments and recognizing Federal laws. In order to receive the land, individual tribal members first had to apply, and then be deemed eligible by the Commission.

The Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes was appointed by President Grover Cleveland in 1893 to negotiate land with the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole tribes. It is commonly called the Dawes Commission, after its chairman, Henry L. Dawes.

In a 1963 episode of the Andy Griffith Show, the main character’s son named Opie was profoundly decisive with informing his Great Aunt, whos name is Aunt Bee, of some very intricate persuasive details that he overheard from a white settler standing nearby.

Aunt Bee knew that the white settlers’ story was inaccurate and very deceiving, but what is true is that white settlers utilized this same exact reasoning in order to acquire the approval of Indian Enrollment eligibility for their personal gain.

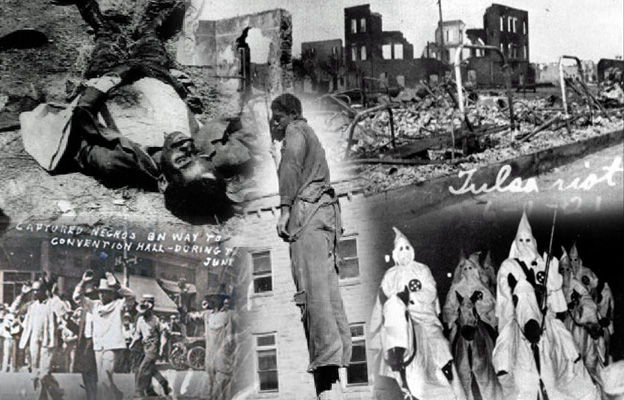

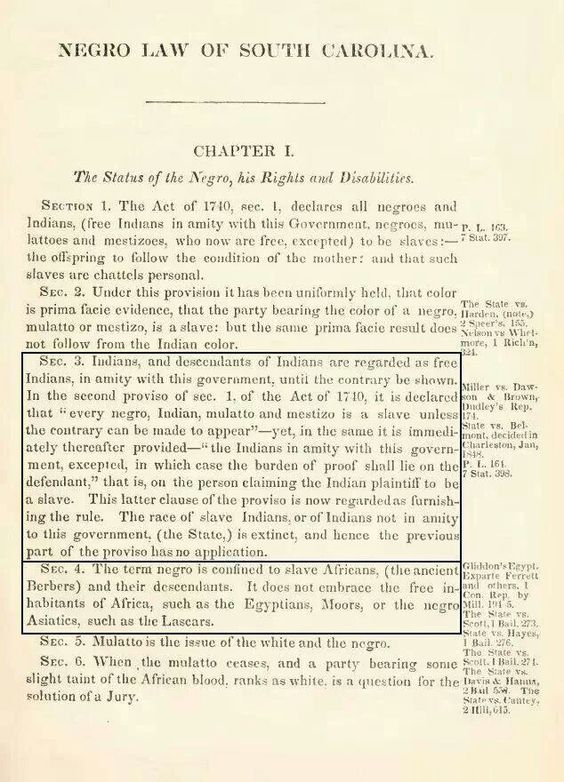

During the early part of the year 1902, the US Government reacted with malicious intent, in developing a separate Freedmens list specifically designed to rule out all ‘copper colored’ Indians from receiving these newly established benefits by way of the Federal Government.

What is also important to note, the US Government listed all full blooded Indigenous Aborigines of America, mainly all of the Indians who they thought had African like features, as “Colored” as their classification of race documented inside of the 1900 Census.

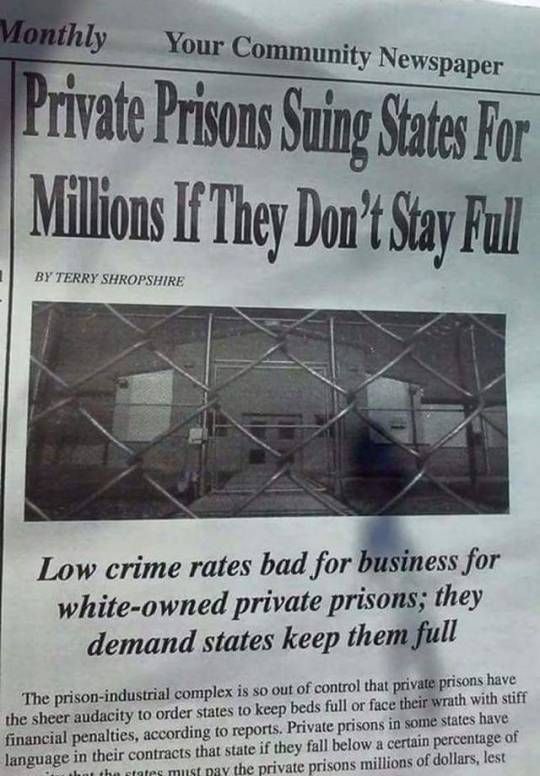

Simultaneously, white U.S. citizens were allowed to become identified as Indians by paying the Dawes Commission a whopping total of just five dollars for each white adult and child to be listed on the Dawes Roll.

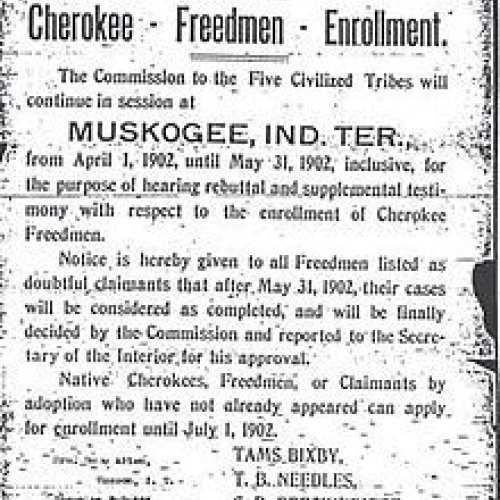

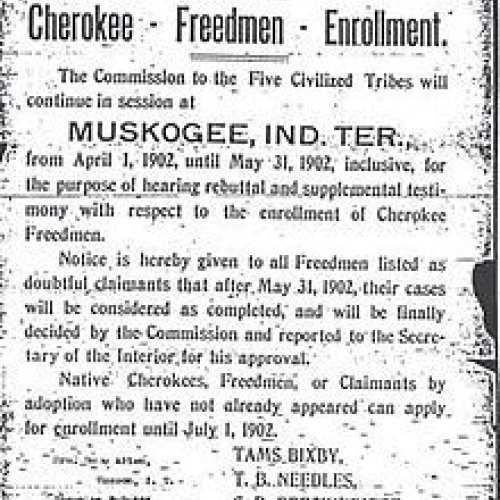

On April 1st, 1902, public notices were passed around, detailing that other “claimants” can legally make their cases for Freedman Enrollment.

Singlehandedly allowing all white citizens the rights to legally steal the Indian lands of America (again), reparations, and optimized benefits set fourth by Federal law. Ironically, this was officially announced on the day most people would tell their very best April Fool’s jokes.

The actual Indians, or rather known as the American Aborigines, have since blamed the government for the mismanagement of a trust in their names, for well over 120 years, and now the US Goverment owes them tens of billions of dollars.

The dispute dates back to 1887, when Congress made the Interior Department the trustee for approximately 145 million acres of Indian lands in America.

Black Indians, or rather Aborigines of America, were supposed to benefit but the government gave the majority of the land, legal tenders, tax reliefs and other federal specialized benefits to white settlers; who paid-off the citizenship administrative organizations, in order to become members of what is known as the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory by Congress.

White settlers sought to reap the benefits of the Aborigines. In fact, one example of that would be the complexity of how successful, but so openly fraudulent they did it.

In 1895, the white settlers were informed of what benefits the Indians were entitled to, so they traveled to the Dawes Roll Commission to inquire about having their names enlisted on the roll cards for full blooded and/or Freedman Indians of America lands.

In 1898, the Dawes Roll acted as a census responsible for documenting records of one’s ethnic backgrounds, in order to determine one’s association with specific American Indian tribes.

Also, it played an important role with determining which Indian tribes would get land allotments and other benefits that I detailed earlier, in return for abolishing their tribal governments and recognizing Federal laws. In order to receive the land, individual tribal members first had to apply, and then be deemed eligible by the Commission.

The Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes was appointed by President Grover Cleveland in 1893 to negotiate land with the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole tribes. It is commonly called the Dawes Commission, after its chairman, Henry L. Dawes.

In a 1963 episode of the Andy Griffith Show, the main character’s son named Opie was profoundly decisive with informing his Great Aunt, whos name is Aunt Bee, of some very intricate persuasive details that he overheard from a white settler standing nearby.

Aunt Bee knew that the white settlers’ story was inaccurate and very deceiving, but what is true is that white settlers utilized this same exact reasoning in order to acquire the approval of Indian Enrollment eligibility for their personal gain.

During the early part of the year 1902, the US Government reacted with malicious intent, in developing a separate Freedmens list specifically designed to rule out all ‘copper colored’ Indians from receiving these newly established benefits by way of the Federal Government.

What is also important to note, the US Government listed all full blooded Indigenous Aborigines of America, mainly all of the Indians who they thought had African like features, as “Colored” as their classification of race documented inside of the 1900 Census.

Simultaneously, white U.S. citizens were allowed to become identified as Indians by paying the Dawes Commission a whopping total of just five dollars for each white adult and child to be listed on the Dawes Roll.

On April 1st, 1902, public notices were passed around, detailing that other “claimants” can legally make their cases for Freedman Enrollment.

Singlehandedly allowing all white citizens the rights to legally steal the Indian lands of America (again), reparations, and optimized benefits set fourth by Federal law. Ironically, this was officially announced on the day most people would tell their very best April Fool’s jokes.

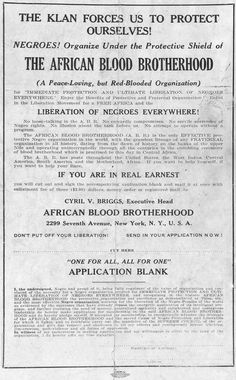

NOTICE

Cherokee • Freedmen • Enrollment

The Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes will continue in session at

MUSKOGEE, IND. TER., from April 1, 1902, until May 31, 1902, inclusive, for the purpose of hearing rebuttal and supplemental testimony with respect to the enrollment of Cherokee Freedman.

Notice is hereby given to all Freedmen listed as doubtful claimants that after May 31, 1902, their cases will be considered as completed, and will be finally decided by the Commission and reported to the Secretary of the Interior for his approval.

Native Cherokees, Freedman, or Claimants by adoption who have not appeared can apply for enrollment until July 1, 1902.

TAMS BIXBY,

T. B. NEEDLES,

C. R. BRECKINRIDGE,

Commissioners