Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Official Protest Thread...

- Thread starter Camille

- Start date

From Slavery to the White House: The Extraordinary Life of Elizabeth Keckly

In 1868, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Hobbs Keckly (also spelled Keckley) published her memoir Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House. This revealing narrative reflected on Elizabeth’s fascinating story, detailing her life experiences from slavery to her successful career as First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker. At the time of its publication, the book was controversial. It soured her close relationship with Mrs. Lincoln and destroyed the reputation of both women. Although the American public was not prepared to read the story of a free Black woman assuming control of her own life narrative at the time of publication, her recollections have been used by many historians to reconstruct the Lincoln White House and better understand one of the nation’s most fascinating and misunderstood first ladies. Her story is integral to White House history and understanding the experiences of enslaved and free Black women.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly was born in February 1818 in Dinwiddie County, Virginia. The circumstances surrounding her birth were complex. Sometime during the spring of 1817, while plantation owner Colonel Armistead Burwell’s wife, Mary, was pregnant with the couple’s tenth child, an enslaved woman named Agnes (Aggy) Hobbs became pregnant by Colonel Burwell. Although it is unknown how this pregnancy came to be and the nature of the relationship between Aggy and Burwell, it is likely the pregnancy was the result of rape or a non-consensual encounter. Despite her parentage, Elizabeth Hobbs was born enslaved. Aggy’s husband, George Pleasant Hobbs, was an enslaved man that worked on a nearby plantation. Even though Elizabeth was not his child, George remained devoted to Agnes and Elizabeth and she considered him her father. Her mother gave her the last name of George’s family, a direct sign of autonomy and resistance. Elizabeth also did not know the truth behind her parentage until later in life. Her name and birth were recorded in a plantation commonplace book by Colonel Burwell’s mother Anne, “Lizzy--child of Aggy/Feby 1818.”

Elizabeth grew up with other enslaved children and assisted her mother in her work as an enslaved domestic servant. Aggy was highly valued by the Burwells. She was well liked by the Burwell children and the family even permitted her to read and write. Aggy also sewed clothing for the family, a skill she taught her daughter.

According to Elizabeth, her first duty as an enslaved five-year-old child was to take care of Burwell's infant daughter, also named Elizabeth. Keckly was very fond of the baby, calling her “my earliest and fondest pet.” She also recalled a severe punishment administered surrounding her care of the baby:

My old mistress encouraged me in rocking the cradle, by telling me that if I would watch over the baby well, keep the flies out of its face, and not let it cry, I should be its little maid. This was a golden promise, and I required no better inducement for the faithful performance of my task. I began to rock the cradle most industriously, when lo! out pitched little pet on the floor. I instantly cried out, "Oh! the baby is on the floor;" and, not knowing what to do, I seized the fire-shovel in my perplexity, and was trying to shovel up my tender charge, when my mistress called to me to let the child alone, and then ordered that I be taken out and lashed for my carelessness. The blows were not administered with a light hand, I assure you, and doubtless the severity of the lashing has made me remember the incident so well. This was the first time I was punished in this cruel way, but not the last.

As Elizabeth grew up, she became increasingly aware of slavery’s cruel practices. In addition to lashings for misbehavior, she remembered Mary Burwell as a “hard task master” and Colonel Burwell for an incident regarding George Hobbs. When Elizabeth was around seven years old, Burwell decided to “reward” Aggy by arranging for George Hobbs to come live with them. According to Elizabeth, her mother was very happy about the move; “The old weary look faded from her face, and she worked as if her heart was in every task.”

Elizabeth (Lizzy) Hobbs Keckly circa 1861.

Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

Unfortunately, these happy moments were short-lived. One day, Colonel Burwell went to the Hobbs’ cabin, and presented the couple with a letter stating that George must join his enslaver in the West. George was given two hours to say goodbye to his family. Elizabeth related the details of the painful separation in her memoir:

The announcement fell upon the little circle in that rude-log cabin like a thunderbolt. I can remember the scene as if it were but yesterday;--how my father cried out against the cruel separation; his last kiss; his wild straining of my mother to his bosom; the solemn prayer to Heaven; the tears and sobs--the fearful anguish of broken hearts. The last kiss, the last good-by; and he, my father, was gone, gone forever.

The separation of the Hobbs family was not unique. Very few enslaved families survived intact and family separations through sale occurred frequently. Enslaved parents lived in persistent fear that either themselves or their children could be sold away at any moment. These separations were usually permanent, as was the case with George Hobbs. Agnes and Elizabeth never saw him again, although he continued to correspond with them. This was a rarity for enslaved people because most were barred from learning to read and write, let alone send letters. One letter read:

Dear Wife: My dear beloved wife I am more than glad to meet with opportunity writee thes few lines to you by my Mistress...I hope with gods helpe that I may be abble to rejoys with you on the earth and In heaven lets meet when will I am detemnid to nuver stope praying, not in this earth and I hope to praise god In glory there weel meet to part no more forever. So my dear wife I hope to meet you In paradase to prase god forever * * * * * I want Elizabeth to be a good girl and not to thinke that becasue I am bound so fare that gods not abble to open the way.

Photograph of Elizabeth Keckly taken circa 1870.

Wikimedia Commons

When Elizabeth was fourteen years old, she was sent to North Carolina to work for Burwell’s son Robert and his new wife. Robert was a Presbyterian minister and made very little money, meaning that Elizabeth was initially their only enslaved servant.

She did not recall her experiences there fondly. Elizabeth was severely whipped, often with no discernible provocation. She was also repeatedly raped by local white store owner Alexander McKenzie Kirkland for four years, beginning in 1838. One of these rapes resulted in a pregnancy and the birth of her only son, George, named after the man she believed to be her father, George Hobbs. Her words about his birth reveal the deep pain that came from her experience: “If my poor boy ever suffered any humiliating pangs on account of birth, he could not blame his mother, for God knows that she did not wish to give him life; he must blame the edicts of that society which deemed it no crime to undermine the virtue of girls in my then position.”

Elizabeth’s painful time in North Carolina came to an end in 1842 when she returned to Virginia. By this time Armistead Burwell had died, and Elizabeth and her son were sent to live with her former mistress, Mary, and her daughter and son-in-law Anne and Hugh A. Garland. At this point she reunited with her mother. Due to financial hardships, Hugh Garland found himself on the brink of bankruptcy in 1845, placing all of his property as collateral against his debts including his enslaved people. Searching for a new opportunity, Garland set out for St. Louis, Missouri in 1846 and the rest of the family, including Agnes and Elizabeth, followed a year later. When the family joined Garland in St. Louis, they found that his fortunes had not improved. Initially, the family planned to hire out Aggy, but Elizabeth strongly objected: “My mother, my poor aged mother, go among strangers to toil for a living! No, a thousand times no!” She confronted Garland and she offered to use her skills as a seamstress in order to make the family money. Elizabeth was soon taking dress orders from “the best ladies in St. Louis.”

With the advantage of the Garland’s connections to white society and Elizabeth’s ability to successfully promote her business and network, she soon became a highly successful businesswoman. She worked in St. Louis for twelve years. It was there that she first caught the attention of a midwestern white woman named Mary Lincoln.

In 1850, a free Black man named James Keckly, who Elizabeth had met back in Virginia, traveled West and asked for her hand in marriage. At first, she refused to consider the proposal because she did not want to be married as an enslaved woman, knowing that any future children would be enslaved. She decided to pursue her freedom, asking Mr. Garland if he would allow her to purchase herself and her son. Although he initially refused, when pressed, he handed Elizabeth a silver dollar and told her: “If you really wish to leave me, take this: it will pay the passage of yourself and boy on the ferry boat.” Elizabeth was shocked by this offer and refused. The recent Compromise of 1850 had resulted in the passage of a strengthened fugitive slave act. Elizabeth knew the offer was hollow and that unless she legally obtained her freedom, she would not be truly free and subject to capture. After discussion, Garland agreed to accept $1,200 for Elizabeth and George. It is likely Garland agreed because she had faithfully served the family for many years and he knew how difficult it would be for her to raise that sum of money.

With a price set for her family’s freedom, she agreed to marry James Keckly. Mr. Garland walked her down the aisle and the entire family celebrated. However, married life soon soured for Keckly. She discovered that her new husband was not a free man but likely a fugitive slave. Elizabeth mentioned him sparingly in her memoir and he quickly faded from her life story. She wrote: “With the simple explanation that I lived with him eight years, let charity draw around him a mantle of silence.”

She found it was quite hard to raise the $1,200 dollars for her freedom. Although she supported the family with her seamstress business, she was still forced to keep up with the household chores for the Garlands and found it difficult to accumulate any savings. Eventually, Mr. Garland died and Anne Garland’s brother, Armistead, arrived in St. Louis to settle his debts. Armistead agreed to honor her original agreement with Hugh Garland. She still needed the money, so she decided to travel to New York in an attempt to raise the funds by appealing to vigilance committees, groups that existed in the North providing assistance to those hoping to achieve their freedom. As she prepared to leave, Mrs. Garland insisted that Keckly obtain the support of six men who could vouch for her and make up the lost money if she failed to return. She obtained the support of five men but could not convince a sixth. Luckily for Elizabeth, her loyal patrons stepped forward. With the help of a Mrs. Le Bourgois, she raised the money for her freedom and on November 13, 1855, Anne Garland signed her emancipation papers: “Know all men that I, Anne P. Garland, of the County and City of St. Louis, State of Missouri, for and in consideration of the sum of $1200, to me in hand paid this day in cash, hereby emancipate my negro woman Lizzie, and her son George…”

After obtaining her freedom, Elizabeth decided to separate from her husband. She continued working in St. Louis as a seamstress for several years, raising money to pay back the loans used to purchase her freedom. During this time, her mother died. Aggy had moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi to live with other Burwell relatives. After paying her debts, Elizabeth left St. Louis in the spring of 1860 and moved to Washington, D.C. where District laws made it difficult to establish herself. She was required to obtain a work permit and also had to find a white person to vouch that she was indeed a free woman. With a limited network in Washington, Elizabeth reached out to a client who started connecting her with many prominent southerners, including Varina Davis, wife of Mississippi Senator and future Confederate President Jefferson Davis. In her memoir, she recounts a conversation with Varina where she asked Elizabeth to accompany her back to the South, telling Elizabeth that there would be a war between the North and the South. Elizabeth agreed to think over the proposal. In the end she chose not to accompany Varina Davis to the South, preferring the North’s chances in the impending conflict: “I preferred to cast my lost [sic] among the people of the North.”

As Varina Davis departed for the South, President-elect Abraham Lincoln arrived in Washington. In the weeks leading up to Lincoln’s inauguration, Keckly was approached by one of her patrons, Margaret McClean. McClean wanted Elizabeth to make a dress for the following Sunday when she would be joining the Lincolns at the Willard Hotel. After Elizabeth refused the offer because of the short notice, Mrs. McClean told her: “I have often heard you say that you would like to work for the ladies of the White House. Well, I have it in my power to obtain you this privilege. I know Mrs. Lincoln well, and you shall make a dress for her provided you finish mine in time to wear at dinner on Sunday.”

Spurred by the potential opportunities of sewing for the White House, Elizabeth worked furiously to finish the dress on time. Mrs. McClean was very pleased with the result and recommended Elizabeth to Mrs. Lincoln. She was already familiar with Elizabeth after hearing about her years earlier from friends in St. Louis. They met before the inauguration at the Willard Hotel and Mrs. Lincoln instructed Elizabeth to go to the White House the day after the inauguration at 8:00 am. When Elizabeth arrived, she discovered three other dress makers. One-by-one the others were dismissed and finally Mrs. Lincoln greeted Elizabeth. The women discussed Keckly’s employment and then she took Mrs. Lincoln’s measurements for a new dress.

Elizabeth returned to the White House ahead of the event for which Mrs. Lincoln wanted the dress. When she arrived, Mrs. Lincoln was enraged, claiming that Elizabeth was late and that she could not go down to the event because she had nothing to wear. After some reasoning, Mrs. Lincoln agreed to wear the dress. President Lincoln entered the room with their sons and declared: “You look charming in that dress. Mrs. Keckley has met with great success.”

Pleased with her work, Mrs. Lincoln continued to employ Elizabeth. Over the course of that spring, Elizabeth sewed fifteen or sixteen dresses for the first lady. When Mary returned to Washington in the fall, she continued to employ Keckly, establishing a strong business relationship. Over time, the women became confidants and Keckly noted that Mrs. Lincoln began calling her “Lizabeth” after she “learned to drop the E.” In her role as Mrs. Lincoln’s seamstress, Elizabeth had a unique view of the White House as the Civil War progressed. She interacted with the Lincolns closely, divulging details of their wartime life in her memoir. When Willie Lincoln passed away on February 20, 1862, Keckly was present. She wrote:

I assisted in washing him and dressing him, and then laid him on the bed, when Mr. Lincoln came in. I never saw a man so bowed down with grief. He came to the bed, lifted the cover from the face of his child, gazed at it long and earnestly, murmuring, "My poor boy, he was too good for this earth. God has called him home. I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!"

Willie’s death bonded the two women as they both mourned the loss of their sons. Elizabeth’s son, George, had joined Union forces and was killed in a bloody skirmish at Wilson’s Creek in Missouri six months earlier. It was his first battle. In the aftermath of Willie’s death, Mrs. Lincoln collapsed, grieving the loss of her son. Her sister stayed with her for a time, but after she left, Mrs. Lincoln wanted a companion and invited Elizabeth to join her on an extended trip to New York and Boston. Mrs. Lincoln wrote to her husband of the trip, “A day of two since, I had one of my severe attacks, if it had not been for Lizzie Keckley, I do not know what I should have done.” Keckly wrote about Mrs. Lincoln’s grief in her memoir, believing the grief changed Mrs. Lincoln while providing detailed accounts. These descriptions later shaped historical analyses of Mary Lincoln and her reaction to the tragic death. In one memorable passage, Keckly recalled a moment where President Lincoln led his wife to the window and pointed towards an asylum saying, “Mother, do you see that large white building on the hill yonder? Try and control your grief, or it will drive you mad, and we may have to send you there.”

African-American refugees at Camp Brightwood in Washington, D.C. As the Civil War progressed, Elizabeth Keckly found time to help found a relief society called the Contraband Relief Association to aid contraband camps in the summer of 1862. President Lincoln donated money to the cause.

Library of Congress

In addition to her dress-making business, Elizabeth found the time to help found a relief society called the Contraband Relief Association to aid

in the summer of 1862. The camps were home to enslaved refugees that flooded into the nation’s capital. Their legal status was unclear. Although they were considered “contrabands of war,” it was not determined whether they were enslaved, free, or something else. After establishing the Association, Keckly approached Mrs. Lincoln about donating to the organization. She wrote to her husband on November 3, 1862:

Elizabeth Keckley, who is with me and is working for the Contraband Association, at Wash[ington]--is authorized...to collect anything for them here that she can….Out of the $1000 fund deposited with you by Gen Corcoran, I have given her the privilege of investing $200 her, in bed covering….Please send check for $200...she will bring you on the bill.

Keckly remained a keen observer of White House life up until President Lincoln’s violent death on April 15, 1865, less than a week after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House. The morning of April 15, a messenger arrived at Keckly’s door and took her by carriage immediately to the White House to console Mrs. Lincoln. Later Elizabeth learned that when the first lady was asked who she would want to have by her side in her grief she responded, “Yes, send for Elizabeth Keckley. I want her just as soon as she can be brought here.” Mrs. Lincoln remained in the White House for several weeks before finally departing. She convinced Keckly to accompany her to Chicago for a short time before Elizabeth returned to Washington with Mrs. Lincoln’s “best wishes for my success in business.”

In 1866, Mary Lincoln, drowning in debt, reached out to Elizabeth Keckly, asking her to meet in New York in September “to assist in disposing of a portion of my wardrobe.” In New York, Elizabeth attempted to find buyers for Mrs. Lincoln’s wardrobe, but the trip was disastrous. In the end, Mrs. Lincoln gave permission to a man named William Brady to stage a public exposition to sell her wardrobe, a decision much discussed and derided in the media. After the trip, Mrs. Lincoln corresponded frequently with Elizabeth who did her best to support and publicly defend the former first lady. She wrote letters to prominent friends in the Black community, asking them to take up offerings for Mrs. Lincoln in churches. She even asked Frederick Douglass to take part in a lecture to raise money, although the lecture ultimately did not come to fruition.

However, Elizabeth also made decisions regarding Mary’s possessions that strained their relationship. She donated Lincoln relics without Mary’s knowledge and granted Brady permission to display the clothing in a traveling exhibition. Mary Lincoln was not pleased as she had been attempting to have the dresses returned. Their relationship frayed and faltered. Elizabeth could not keep up with Mrs. Lincoln’s letters and demands and started to back away from the relationship.

Photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln taken in 1861 by photographer Matthew Brady

Library of Congress

At the same time, Elizabeth was working on her memoir. She published Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House in 1868, detailing her life story, but also including details of the disastrous dress selling saga. Keckly believed that writing this story would redeem her own character as well as Mrs. Lincoln’s. Unfortunately, the book was not well received for several reasons. By writing down the story of her enslavement, her intimate conversations with Washington’s elite women, and her relationship with Mary Lincoln, Keckly violated social norms of privacy, race, class, and gender. Although other formerly enslaved people like Frederick Douglass wrote generally well received memoirs during the same time period, Keckly’s was more divisive. Her choice to publish correspondence between herself and Mary Lincoln was seen as an infringement on the former first lady’s privacy. Keckly attempted to address this critique in the preface to her memoir:

If I have betrayed confidence in anything I have published, it has been to place Mrs. Lincoln in a better light before the world. A breach of trust--if breach it can be called--of this kind is always excusable. My own character, as well as the character of Mrs. Lincoln, is at stake, since I have been intimately associated with that lady in the most eventful periods of her life. I have been her confidante, and if evil charges are laid at her door, they also must be laid at mine, since I have been a party to all her movements. To defend myself I must defend the lady that I have served. The world have judged Mrs. Lincoln by the facts which float upon the surface, and through her have partially judged me, and the only way to convince them that wrong was not meditated is to explain the motives that actuated us.

The media began attacking her directly, with some groups arguing that the book was an example of why Black women should not be educated. Her position in society as a free Black woman writing a memoir that disclosed personal information about Washington’s white elite was simply unacceptable at the time. Keckly fought back against these attacks arguing that nothing she wrote about Mrs. Lincoln compared to the consistent abuse she suffered at the hands of the newspapers in the wake of the dress selling scandal. Although the book caused quite a stir upon its publication, it soon faded to the background. The book did not sell many copies and Elizabeth believed that may have been successful in suppressing its publication.

Cover page of Elizabeth Keckly's controversial memoir, Behind the Scenes, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House.

Documenting the American South

Mary Lincoln read the memoir a few weeks after its release. She felt betrayed by the intimate details and conversations described and refused to mention Keckly’s name again. Elizabeth Keckly continued sewing after the book’s publication, but some of her customers disappeared. She later began training Black seamstresses and passed on her knowledge. In 1892, she accepted a position as the head of Wilberforce University’s Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts and moved to Ohio before returning to Washington after suffering a possible stroke. She died in 1907 at the age of eighty-nine, after living an extraordinary and remarkable life.

www.whitehousehistory.org

www.whitehousehistory.org

The announcement fell upon the little circle in that rude-log cabin like a thunderbolt. I can remember the scene as if it were but yesterday;--how my father cried out against the cruel separation; his last kiss; his wild straining of my mother to his bosom; the solemn prayer to Heaven; the tears and sobs--the fearful anguish of broken hearts. The last kiss, the last good-by; and he, my father, was gone, gone forever.

The separation of the Hobbs family was not unique. Very few enslaved families survived intact and family separations through sale occurred frequently. Enslaved parents lived in persistent fear that either themselves or their children could be sold away at any moment. These separations were usually permanent, as was the case with George Hobbs. Agnes and Elizabeth never saw him again, although he continued to correspond with them. This was a rarity for enslaved people because most were barred from learning to read and write, let alone send letters. One letter read:

Dear Wife: My dear beloved wife I am more than glad to meet with opportunity writee thes few lines to you by my Mistress...I hope with gods helpe that I may be abble to rejoys with you on the earth and In heaven lets meet when will I am detemnid to nuver stope praying, not in this earth and I hope to praise god In glory there weel meet to part no more forever. So my dear wife I hope to meet you In paradase to prase god forever * * * * * I want Elizabeth to be a good girl and not to thinke that becasue I am bound so fare that gods not abble to open the way.

Photograph of Elizabeth Keckly taken circa 1870.

Wikimedia Commons

When Elizabeth was fourteen years old, she was sent to North Carolina to work for Burwell’s son Robert and his new wife. Robert was a Presbyterian minister and made very little money, meaning that Elizabeth was initially their only enslaved servant.

She did not recall her experiences there fondly. Elizabeth was severely whipped, often with no discernible provocation. She was also repeatedly raped by local white store owner Alexander McKenzie Kirkland for four years, beginning in 1838. One of these rapes resulted in a pregnancy and the birth of her only son, George, named after the man she believed to be her father, George Hobbs. Her words about his birth reveal the deep pain that came from her experience: “If my poor boy ever suffered any humiliating pangs on account of birth, he could not blame his mother, for God knows that she did not wish to give him life; he must blame the edicts of that society which deemed it no crime to undermine the virtue of girls in my then position.”

Elizabeth’s painful time in North Carolina came to an end in 1842 when she returned to Virginia. By this time Armistead Burwell had died, and Elizabeth and her son were sent to live with her former mistress, Mary, and her daughter and son-in-law Anne and Hugh A. Garland. At this point she reunited with her mother. Due to financial hardships, Hugh Garland found himself on the brink of bankruptcy in 1845, placing all of his property as collateral against his debts including his enslaved people. Searching for a new opportunity, Garland set out for St. Louis, Missouri in 1846 and the rest of the family, including Agnes and Elizabeth, followed a year later. When the family joined Garland in St. Louis, they found that his fortunes had not improved. Initially, the family planned to hire out Aggy, but Elizabeth strongly objected: “My mother, my poor aged mother, go among strangers to toil for a living! No, a thousand times no!” She confronted Garland and she offered to use her skills as a seamstress in order to make the family money. Elizabeth was soon taking dress orders from “the best ladies in St. Louis.”

With the advantage of the Garland’s connections to white society and Elizabeth’s ability to successfully promote her business and network, she soon became a highly successful businesswoman. She worked in St. Louis for twelve years. It was there that she first caught the attention of a midwestern white woman named Mary Lincoln.

In 1850, a free Black man named James Keckly, who Elizabeth had met back in Virginia, traveled West and asked for her hand in marriage. At first, she refused to consider the proposal because she did not want to be married as an enslaved woman, knowing that any future children would be enslaved. She decided to pursue her freedom, asking Mr. Garland if he would allow her to purchase herself and her son. Although he initially refused, when pressed, he handed Elizabeth a silver dollar and told her: “If you really wish to leave me, take this: it will pay the passage of yourself and boy on the ferry boat.” Elizabeth was shocked by this offer and refused. The recent Compromise of 1850 had resulted in the passage of a strengthened fugitive slave act. Elizabeth knew the offer was hollow and that unless she legally obtained her freedom, she would not be truly free and subject to capture. After discussion, Garland agreed to accept $1,200 for Elizabeth and George. It is likely Garland agreed because she had faithfully served the family for many years and he knew how difficult it would be for her to raise that sum of money.

With a price set for her family’s freedom, she agreed to marry James Keckly. Mr. Garland walked her down the aisle and the entire family celebrated. However, married life soon soured for Keckly. She discovered that her new husband was not a free man but likely a fugitive slave. Elizabeth mentioned him sparingly in her memoir and he quickly faded from her life story. She wrote: “With the simple explanation that I lived with him eight years, let charity draw around him a mantle of silence.”

She found it was quite hard to raise the $1,200 dollars for her freedom. Although she supported the family with her seamstress business, she was still forced to keep up with the household chores for the Garlands and found it difficult to accumulate any savings. Eventually, Mr. Garland died and Anne Garland’s brother, Armistead, arrived in St. Louis to settle his debts. Armistead agreed to honor her original agreement with Hugh Garland. She still needed the money, so she decided to travel to New York in an attempt to raise the funds by appealing to vigilance committees, groups that existed in the North providing assistance to those hoping to achieve their freedom. As she prepared to leave, Mrs. Garland insisted that Keckly obtain the support of six men who could vouch for her and make up the lost money if she failed to return. She obtained the support of five men but could not convince a sixth. Luckily for Elizabeth, her loyal patrons stepped forward. With the help of a Mrs. Le Bourgois, she raised the money for her freedom and on November 13, 1855, Anne Garland signed her emancipation papers: “Know all men that I, Anne P. Garland, of the County and City of St. Louis, State of Missouri, for and in consideration of the sum of $1200, to me in hand paid this day in cash, hereby emancipate my negro woman Lizzie, and her son George…”

After obtaining her freedom, Elizabeth decided to separate from her husband. She continued working in St. Louis as a seamstress for several years, raising money to pay back the loans used to purchase her freedom. During this time, her mother died. Aggy had moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi to live with other Burwell relatives. After paying her debts, Elizabeth left St. Louis in the spring of 1860 and moved to Washington, D.C. where District laws made it difficult to establish herself. She was required to obtain a work permit and also had to find a white person to vouch that she was indeed a free woman. With a limited network in Washington, Elizabeth reached out to a client who started connecting her with many prominent southerners, including Varina Davis, wife of Mississippi Senator and future Confederate President Jefferson Davis. In her memoir, she recounts a conversation with Varina where she asked Elizabeth to accompany her back to the South, telling Elizabeth that there would be a war between the North and the South. Elizabeth agreed to think over the proposal. In the end she chose not to accompany Varina Davis to the South, preferring the North’s chances in the impending conflict: “I preferred to cast my lost [sic] among the people of the North.”

As Varina Davis departed for the South, President-elect Abraham Lincoln arrived in Washington. In the weeks leading up to Lincoln’s inauguration, Keckly was approached by one of her patrons, Margaret McClean. McClean wanted Elizabeth to make a dress for the following Sunday when she would be joining the Lincolns at the Willard Hotel. After Elizabeth refused the offer because of the short notice, Mrs. McClean told her: “I have often heard you say that you would like to work for the ladies of the White House. Well, I have it in my power to obtain you this privilege. I know Mrs. Lincoln well, and you shall make a dress for her provided you finish mine in time to wear at dinner on Sunday.”

Spurred by the potential opportunities of sewing for the White House, Elizabeth worked furiously to finish the dress on time. Mrs. McClean was very pleased with the result and recommended Elizabeth to Mrs. Lincoln. She was already familiar with Elizabeth after hearing about her years earlier from friends in St. Louis. They met before the inauguration at the Willard Hotel and Mrs. Lincoln instructed Elizabeth to go to the White House the day after the inauguration at 8:00 am. When Elizabeth arrived, she discovered three other dress makers. One-by-one the others were dismissed and finally Mrs. Lincoln greeted Elizabeth. The women discussed Keckly’s employment and then she took Mrs. Lincoln’s measurements for a new dress.

Elizabeth returned to the White House ahead of the event for which Mrs. Lincoln wanted the dress. When she arrived, Mrs. Lincoln was enraged, claiming that Elizabeth was late and that she could not go down to the event because she had nothing to wear. After some reasoning, Mrs. Lincoln agreed to wear the dress. President Lincoln entered the room with their sons and declared: “You look charming in that dress. Mrs. Keckley has met with great success.”

Pleased with her work, Mrs. Lincoln continued to employ Elizabeth. Over the course of that spring, Elizabeth sewed fifteen or sixteen dresses for the first lady. When Mary returned to Washington in the fall, she continued to employ Keckly, establishing a strong business relationship. Over time, the women became confidants and Keckly noted that Mrs. Lincoln began calling her “Lizabeth” after she “learned to drop the E.” In her role as Mrs. Lincoln’s seamstress, Elizabeth had a unique view of the White House as the Civil War progressed. She interacted with the Lincolns closely, divulging details of their wartime life in her memoir. When Willie Lincoln passed away on February 20, 1862, Keckly was present. She wrote:

I assisted in washing him and dressing him, and then laid him on the bed, when Mr. Lincoln came in. I never saw a man so bowed down with grief. He came to the bed, lifted the cover from the face of his child, gazed at it long and earnestly, murmuring, "My poor boy, he was too good for this earth. God has called him home. I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!"

Willie’s death bonded the two women as they both mourned the loss of their sons. Elizabeth’s son, George, had joined Union forces and was killed in a bloody skirmish at Wilson’s Creek in Missouri six months earlier. It was his first battle. In the aftermath of Willie’s death, Mrs. Lincoln collapsed, grieving the loss of her son. Her sister stayed with her for a time, but after she left, Mrs. Lincoln wanted a companion and invited Elizabeth to join her on an extended trip to New York and Boston. Mrs. Lincoln wrote to her husband of the trip, “A day of two since, I had one of my severe attacks, if it had not been for Lizzie Keckley, I do not know what I should have done.” Keckly wrote about Mrs. Lincoln’s grief in her memoir, believing the grief changed Mrs. Lincoln while providing detailed accounts. These descriptions later shaped historical analyses of Mary Lincoln and her reaction to the tragic death. In one memorable passage, Keckly recalled a moment where President Lincoln led his wife to the window and pointed towards an asylum saying, “Mother, do you see that large white building on the hill yonder? Try and control your grief, or it will drive you mad, and we may have to send you there.”

African-American refugees at Camp Brightwood in Washington, D.C. As the Civil War progressed, Elizabeth Keckly found time to help found a relief society called the Contraband Relief Association to aid contraband camps in the summer of 1862. President Lincoln donated money to the cause.

Library of Congress

In addition to her dress-making business, Elizabeth found the time to help found a relief society called the Contraband Relief Association to aid

in the summer of 1862. The camps were home to enslaved refugees that flooded into the nation’s capital. Their legal status was unclear. Although they were considered “contrabands of war,” it was not determined whether they were enslaved, free, or something else. After establishing the Association, Keckly approached Mrs. Lincoln about donating to the organization. She wrote to her husband on November 3, 1862:

Elizabeth Keckley, who is with me and is working for the Contraband Association, at Wash[ington]--is authorized...to collect anything for them here that she can….Out of the $1000 fund deposited with you by Gen Corcoran, I have given her the privilege of investing $200 her, in bed covering….Please send check for $200...she will bring you on the bill.

Keckly remained a keen observer of White House life up until President Lincoln’s violent death on April 15, 1865, less than a week after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House. The morning of April 15, a messenger arrived at Keckly’s door and took her by carriage immediately to the White House to console Mrs. Lincoln. Later Elizabeth learned that when the first lady was asked who she would want to have by her side in her grief she responded, “Yes, send for Elizabeth Keckley. I want her just as soon as she can be brought here.” Mrs. Lincoln remained in the White House for several weeks before finally departing. She convinced Keckly to accompany her to Chicago for a short time before Elizabeth returned to Washington with Mrs. Lincoln’s “best wishes for my success in business.”

In 1866, Mary Lincoln, drowning in debt, reached out to Elizabeth Keckly, asking her to meet in New York in September “to assist in disposing of a portion of my wardrobe.” In New York, Elizabeth attempted to find buyers for Mrs. Lincoln’s wardrobe, but the trip was disastrous. In the end, Mrs. Lincoln gave permission to a man named William Brady to stage a public exposition to sell her wardrobe, a decision much discussed and derided in the media. After the trip, Mrs. Lincoln corresponded frequently with Elizabeth who did her best to support and publicly defend the former first lady. She wrote letters to prominent friends in the Black community, asking them to take up offerings for Mrs. Lincoln in churches. She even asked Frederick Douglass to take part in a lecture to raise money, although the lecture ultimately did not come to fruition.

However, Elizabeth also made decisions regarding Mary’s possessions that strained their relationship. She donated Lincoln relics without Mary’s knowledge and granted Brady permission to display the clothing in a traveling exhibition. Mary Lincoln was not pleased as she had been attempting to have the dresses returned. Their relationship frayed and faltered. Elizabeth could not keep up with Mrs. Lincoln’s letters and demands and started to back away from the relationship.

Photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln taken in 1861 by photographer Matthew Brady

Library of Congress

At the same time, Elizabeth was working on her memoir. She published Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House in 1868, detailing her life story, but also including details of the disastrous dress selling saga. Keckly believed that writing this story would redeem her own character as well as Mrs. Lincoln’s. Unfortunately, the book was not well received for several reasons. By writing down the story of her enslavement, her intimate conversations with Washington’s elite women, and her relationship with Mary Lincoln, Keckly violated social norms of privacy, race, class, and gender. Although other formerly enslaved people like Frederick Douglass wrote generally well received memoirs during the same time period, Keckly’s was more divisive. Her choice to publish correspondence between herself and Mary Lincoln was seen as an infringement on the former first lady’s privacy. Keckly attempted to address this critique in the preface to her memoir:

If I have betrayed confidence in anything I have published, it has been to place Mrs. Lincoln in a better light before the world. A breach of trust--if breach it can be called--of this kind is always excusable. My own character, as well as the character of Mrs. Lincoln, is at stake, since I have been intimately associated with that lady in the most eventful periods of her life. I have been her confidante, and if evil charges are laid at her door, they also must be laid at mine, since I have been a party to all her movements. To defend myself I must defend the lady that I have served. The world have judged Mrs. Lincoln by the facts which float upon the surface, and through her have partially judged me, and the only way to convince them that wrong was not meditated is to explain the motives that actuated us.

The media began attacking her directly, with some groups arguing that the book was an example of why Black women should not be educated. Her position in society as a free Black woman writing a memoir that disclosed personal information about Washington’s white elite was simply unacceptable at the time. Keckly fought back against these attacks arguing that nothing she wrote about Mrs. Lincoln compared to the consistent abuse she suffered at the hands of the newspapers in the wake of the dress selling scandal. Although the book caused quite a stir upon its publication, it soon faded to the background. The book did not sell many copies and Elizabeth believed that may have been successful in suppressing its publication.

Cover page of Elizabeth Keckly's controversial memoir, Behind the Scenes, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House.

Documenting the American South

Mary Lincoln read the memoir a few weeks after its release. She felt betrayed by the intimate details and conversations described and refused to mention Keckly’s name again. Elizabeth Keckly continued sewing after the book’s publication, but some of her customers disappeared. She later began training Black seamstresses and passed on her knowledge. In 1892, she accepted a position as the head of Wilberforce University’s Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts and moved to Ohio before returning to Washington after suffering a possible stroke. She died in 1907 at the age of eighty-nine, after living an extraordinary and remarkable life.

From Slavery to the White House: The Extraordinary Life of Elizabeth Keckly

In 1868, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Hobbs Keckly (also spelled Keckley) published her memoir Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a...

6 Myths About the History of Black People in America

Six historians weigh in on the biggest misconceptions about Black history, including the Tuskegee experiment and enslaved people’s finances.

6 Myths About the History of Black People in America

Six historians weigh in on the biggest misconceptions about Black history, including the Tuskegee experiment and enslaved people’s finances.

To study American history is often an exercise in learning partial truths and patriotic fables. Textbooks and curricula throughout the country continue to center the white experience, with Black people often quarantined to a short section about slavery and quotes by Martin Luther King Jr. Many walk away from their high school history class — and through the world — with a severe lack of understanding of the history and perspective of Black people in America.

In the summer of 2019, the New York Times’s 1619 Project burst open a long-overdue conversation about how stories of Black Americans need to be told through the lens of Black Americans themselves. In this tradition, and in celebration of Black History Month, Vox has asked six Black scholars and historians about myths that perpetuate about Black history. Ultimately, understanding Black history is more than learning about the brutality and oppression Black people have endured — it’s about the ways they have fought to survive and thrive in America.

But many also had money. Enslaved people actively participated in the informal and formal market economy. They saved money earned from overwork, from hiring themselves out, and through independent economic activities with banks, local merchants, and their enslavers. Elizabeth Keckley, a skilled seamstress whose dresses for Abraham Lincoln’s wife are displayed in Smithsonian museums, supported her enslaver’s entire family and still earned enough to pay for her freedom.

Free and enslaved market women dominated local marketplaces, including in Savannah and Charleston, controlling networks that crisscrossed the countryside. They ensured fresh supplies of fruits, vegetables, and eggs for the markets, as well as a steady flow of cash to enslaved people. Whites described these women as “loose” and “disorderly” to criticize their actions as unacceptable behavior for women, but white people of all classes depended on them for survival.

Illustrated portrait of Elizabeth Keckley (1818-1907), a formerly enslaved woman who bought her freedom and became dressmaker for first lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In fact, enslaved people also created financial institutions, especially mutual aid societies. Eliza Allen helped form at least three secret societies for women on her own and nearby plantations in Petersburg, Virginia. One of her societies, Sisters of Usefulness, could have had as many as two to three dozen members. Cities like Baltimore even passed laws against these societies — a sure sign of their popularity. Other cities reluctantly tolerated them, requiring that a white person be present at meetings. Enslaved people, however, found creative ways to conduct their societies under white people’s noses. Often, the treasurer’s ledger listed members by numbers so that, in case of discovery, members’ identities remained protected.

During the tumult of the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of Black people sought refuge behind Union lines. Most were impoverished, but a few managed to bring with them wealth they had stashed under beds, in private chests, and in other hiding places. After the war, Black people fought through the Southern Claims Commission for the return of the wealth Union and Confederate soldiers impounded or outright stole.

Given the resurgence of attention on reparations for slavery and the racial wealth gap, it is important to recall the long history of black people’s engagement with the US economy — not just as property, but as savers, spenders, and small businesspeople.

Shennette Garrett-Scott is an associate professor of history and African American Studies at the University of Mississippi and the author of Banking on Freedom: Black Women in US Finance Before the New Deal.

Painting of the 1770 Boston Massacre showing Crispus Attucks, one of the leaders of the demonstration and one of the five men killed by the gunfire of the British troops. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

First off, Black revolutionary soldiers did not fight out of love for a country that enslaved and oppressed them. Black revolutionary soldiers were fighting for freedom — not for America, but for themselves and the race as a whole. In fact, the American Revolution is a case study of interest convergence. Interest convergence denotes that within racial states such as the 13 colonies, any progress made for Black people can only be made if that progress also benefits the dominant culture — in this case the liberation of the white colonists of America. In other words, colonists’ enlistment of Black people was not out of some moral mandate, but based on manpower needs to win the war.

In 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia who wanted to quickly end the war, issued a proclamation to free enslaved Black people if they defected from the colonies and fought for the British army. In response, George Washington revised the policy that restricted Black persons (free or enslaved) from joining his Continental Army. His reversal was based in a convergence of his interests: competing with a growing British military, securing the slave economy, and increasing labor needs for the Continental Army. When enslaved persons left the plantation, this caused serious social and economic unrest in the colonies. These defections were encouragement for many white plantation owners to join the Patriotic cause even if they previously held reservations.

Washington also saw other benefits in Black enlistment: White revolutionary soldiers only fought in three- to four-month increments and returned to their farms or plantation, but many Black soldiers could serve longer terms. The need for the Black soldier was essential for the war effort, and the need to win the war became greater than racial or racist ideology.

Interests converged with those of Black revolutionary soldiers as well. Once the American colonies promised freedom, about a quarter of the Continental Army became Black; before that, more Black people defected to the British military for a chance to be free. Black revolutionary soldiers understood the stakes of the war and realized that they could also benefit and leave bondage. As historian Gary Nash has said, the Black revolutionary soldier “can best be understood by realizing that his major loyalty was not to a place, not to a people, but to a principle.”

Black people played a dual role — service with the American forces and fleeing to the British — both for freedom. The notion of the Black Patriot is a misused term. In many ways, while the majority of the whites were fighting in the American Revolution, Black revolutionary soldiers were fighting the “African Americans’ Revolution.”

LaGarrett King is an education professor at the University of Missouri Columbia and the founding director of the Carter Center for K-12 Black History Education.

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male emerged from a study group formed in 1932 connected with the venereal disease section of the US Public Health Service. The purpose of the experiment was to test the impact of syphilis untreated and was conducted at what is now Tuskegee University, a historically Black university in Macon County, Alabama.

The 600 Black men in the experiment were not given syphilis. Instead, 399 men already had stages of the disease, and the 201 who did not served as a control group. Both groups were withheld from treatment of any kind for the 40 years they were observed. The men were subjected to humiliating and often painfully invasive tests and experiments including spinal taps.

Deemed uneducated and impoverished sharecroppers, these men were lured by free medical examinations, hot meals, free treatment for minor injuries, rides to and from the hospital, and guaranteed burial stipends (up to $50) to be paid to their survivors. The study also did not occur in total secret, and several African American health workers and educators associated with the Tuskegee Institute assisted in the study.

By the end of the study in the summer of 1972, after a whistleblower exposed the story in national headlines, only 74 of the test subjects were still alive. From the original 399 infected men, 28 had died of syphilis, 100 others from related complications. Forty of the men’s wives had been infected, and an estimated 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis.

As a result of the case, the US Department of Health and Human Services established the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) in 1974 to oversee clinical trials. The case also solidified the idea of African Americans being cast and used as medical guinea pigs.

An unfortunate side effect of both the truth of medical racism and the myth of syphilis injection, however, is it tangibly reinforces the inability to place trust in the medical system for some African Americans who may not choose to seek out assistance, and as a result put themselves in danger.

Sowande Mustakeem is an associate professor of History and African & African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis.

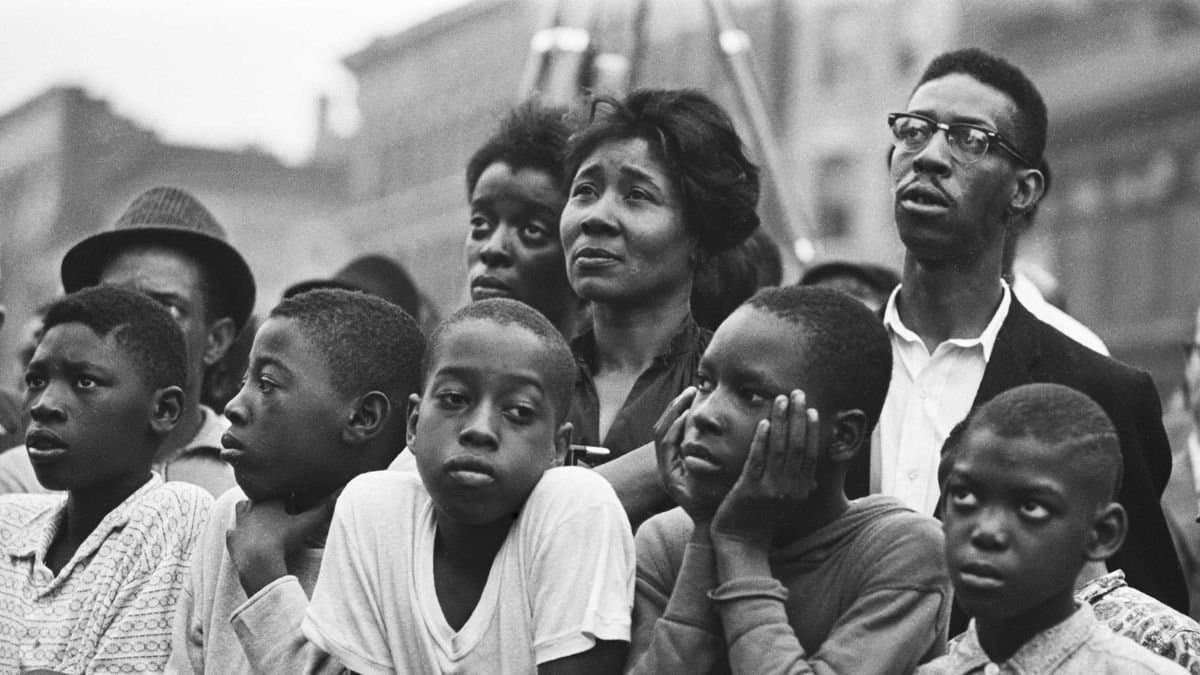

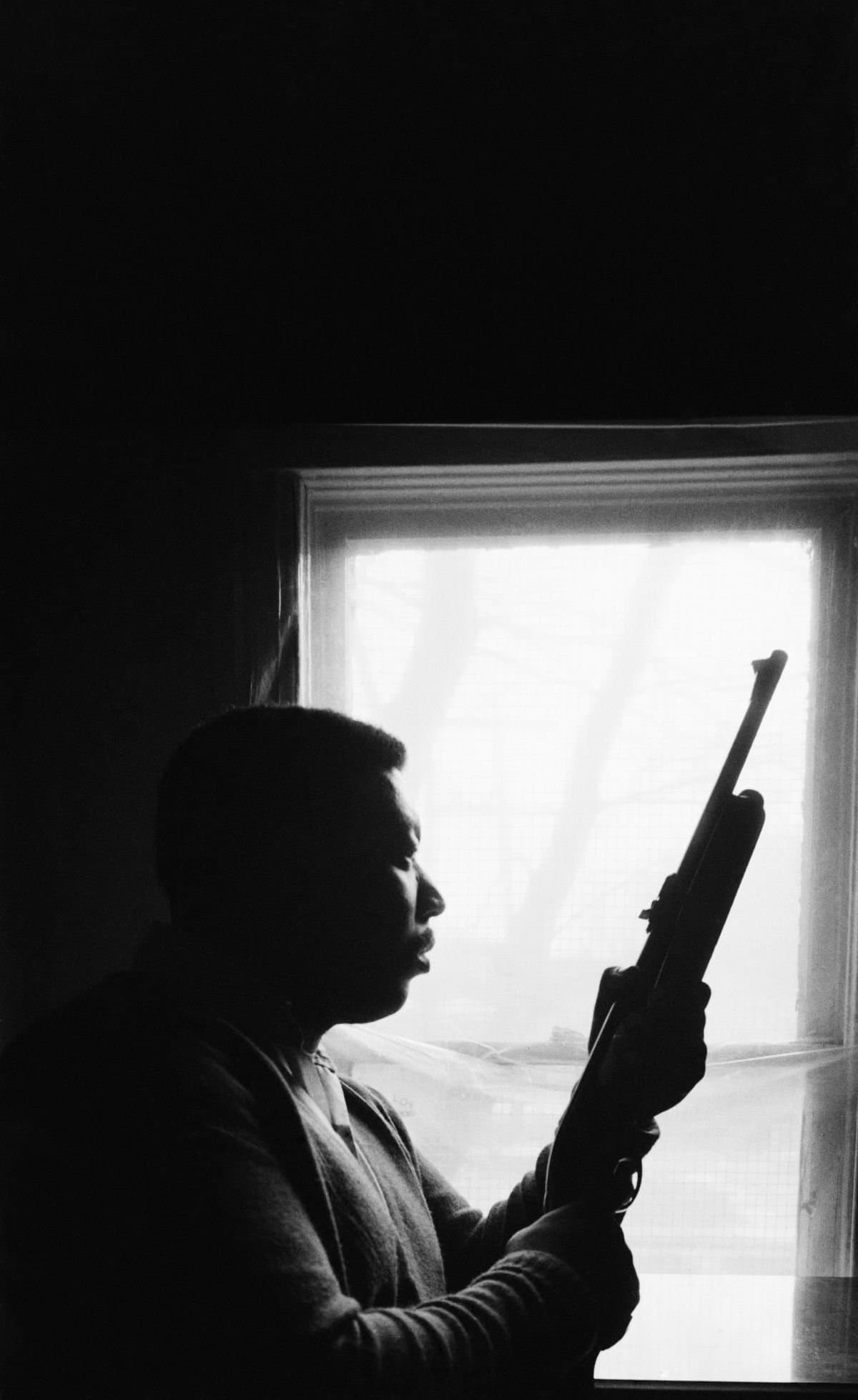

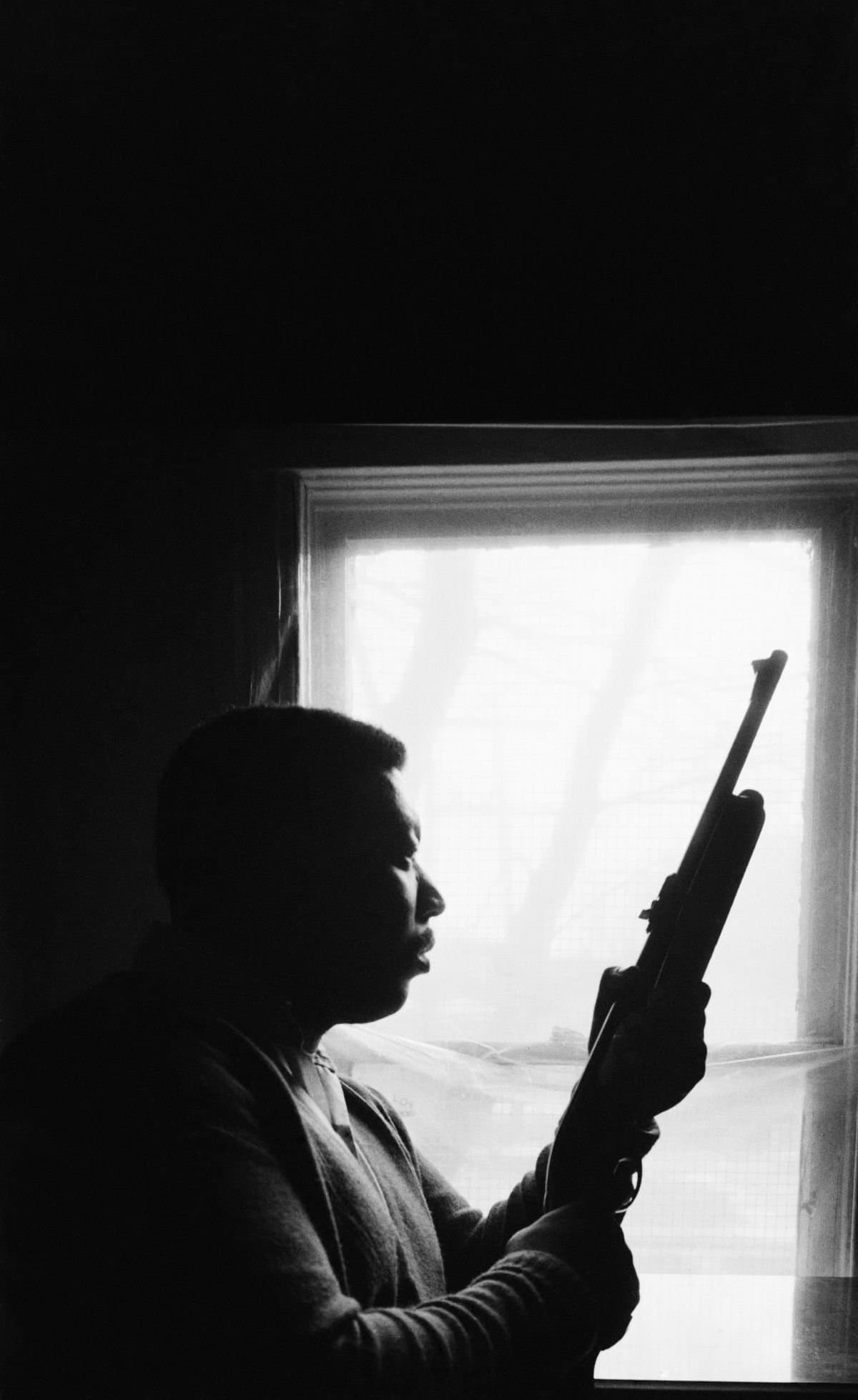

An unidentified member of the Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party stands guard with a shotgun on December 11, 1969. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In the face of this violence, some African Americans prepared themselves physically and psychologically for the abuse they expected — and they fought back. Distressed by public racial violence and unwilling to accept it, many adhered to emerging ideologies of outright rebellion, particularly after the turn of the 20th century and the emergence of the “New Negro.” Urban, more educated than their parents, and often trained militarily, a generation coming of age following World War I sought to secure themselves in the only ways left. Many believed, as Marcus Garvey once told a Harlem audience, that Black folks would never gain freedom “by praying for it.”

For New Negroes, the comparatively tame efforts of groups like the NAACP were not urgent enough. Most notably, they defended themselves fiercely nationwide during the bloodshed of the Red Summer of 1919 when whites attacked African Americans in multiple cities across the country. Whites may have initiated most race riots in the early Jim Crow era, but some also happened as Black people rejected the limitations placed on their life, leisure, and labor, and when they refused to fold under the weight of white supremacy. The magnitude of racial and state violence often came down upon Black people who defended themselves from police and citizens, but that did not stop some from sparking personal and collective insurrections.

Douglas J. Flowe is an assistant professor of history at Washington University in St. Louis.

Even though more white people reported using crack more than Black people in a 1991 National Institute on Drug Abuse survey, Black people were sentenced for crack offenses eight times more than whites. Meanwhile, there was a corresponding cocaine epidemic in white suburbs and college campuses that compelled the US to install harsher penalties for crack than for cocaine. For example, in 1986, before the enactment of federal mandatory minimum sentencing for crack cocaine offenses, the average federal drug sentence for African Americans was 11 percent higher than for whites. Four years later, the average federal drug sentence for African Americans was 49 percent higher.

Even through the ’90s and beyond, the media and supposed liberal allies, like Hillary Clinton, designated Black children and teens as drug-dealing “superpredators” to mostly white audiences. The criminalization of people of color during the crack epidemic made mainstream white Americans comfortable knowing that this was a contained black-on-black problem.

It also left white America unprepared to deal with the approach of the opioid epidemic, which is often a white-on-white crime whose dealers will evade prison (see: the Sacklers, the billionaire family behind Oxycontin who has served no jail time; and Johnson & Johnson, which got a $107 million break in fines when it was found liable for marketing practices that led to thousands of overdose deaths). Unlike Black Americans who are sent to prison, these white dealers retain their right to vote, lobby, and hold on to their wealth.

Jason Allen is a public historian and facilitator at xCHANGEs, a cultural diversity and inclusion training consultancy.

In reality, free Black and Black-white biracial communities existed in states such as Louisiana, Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio well before abolition. For example, Anthony Johnson, named Antonio the Negro on the 1625 census, was listed on this document as a servant. By 1640, he and his wife owned and managed a large plot of land in Virginia.

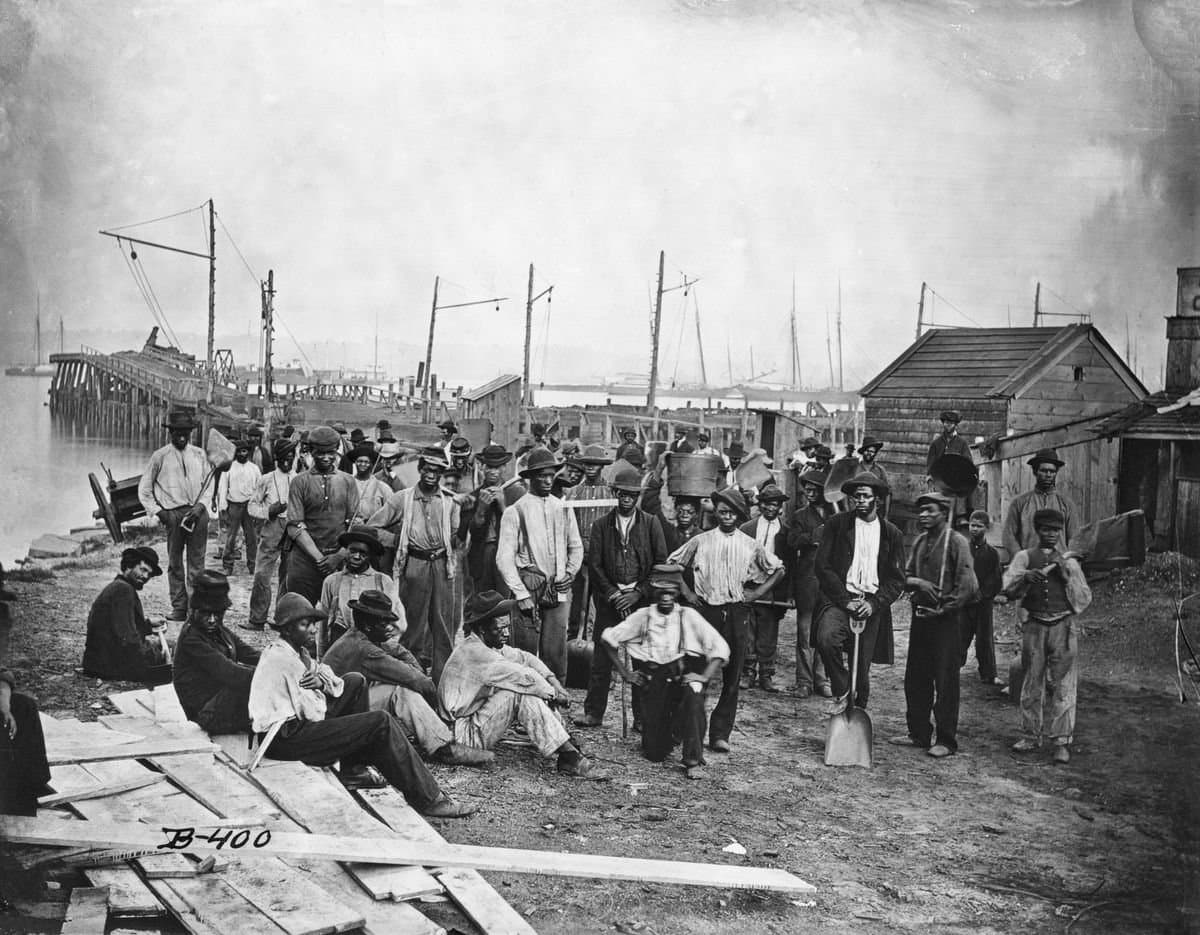

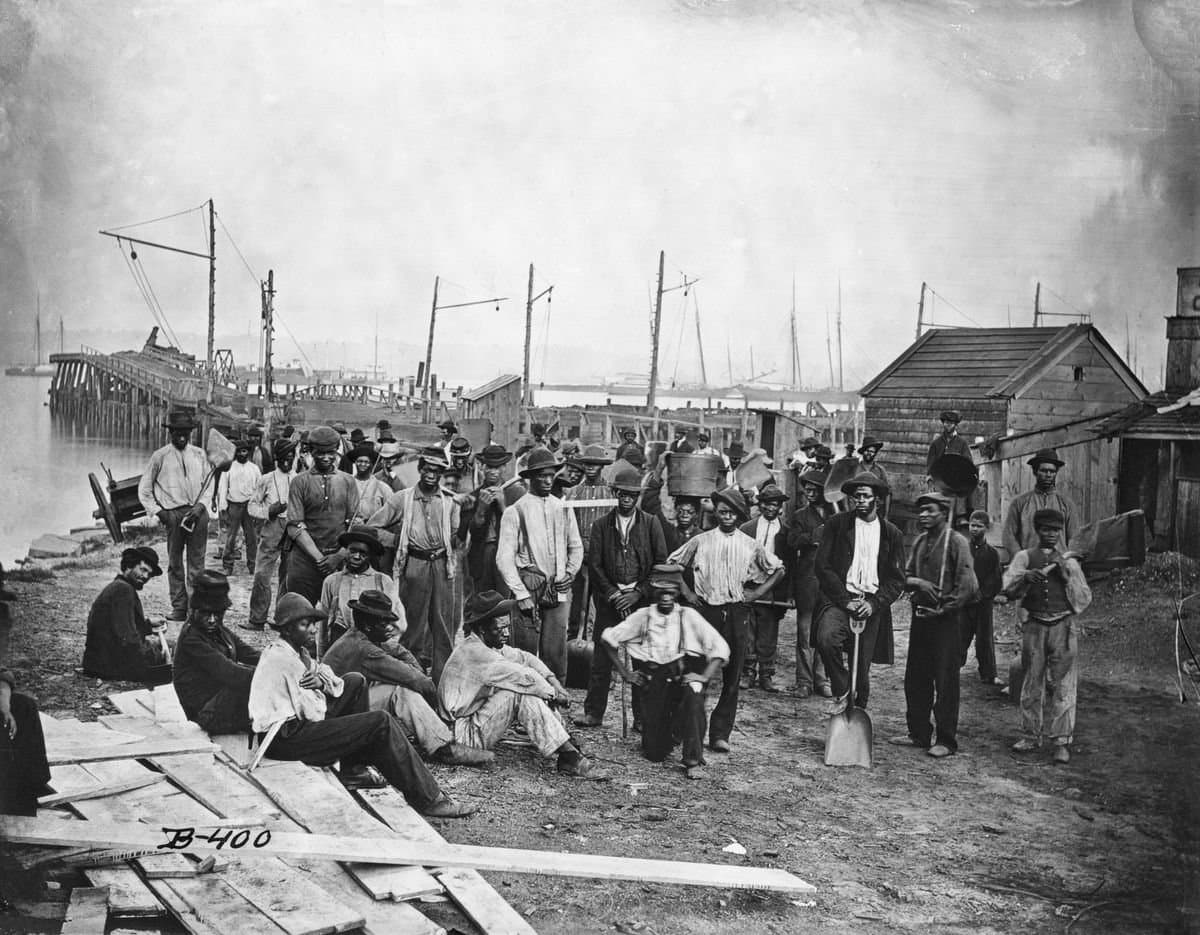

A group of free African Americans in an unknown city, circa 1860. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Some enslaved Africans were able to sell their labor or craftsmanship to others, thereby earning enough money to purchase their freedom. Such was the case for Richard Allen, who paid for his freedom in 1786 and co-founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church less than a decade later. After the American Revolutionary War, Robert Carter III committed the largest manumission — or freeing of slaves — before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, freeing his 100 enslaved Africans.

Not all emancipations were large. Individuals or families were sometimes freed upon the death of their enslaver and his family. And many escaped and lived free in the North or in Canada. Finally, there were generations of children born in free Black and biracial communities, many who never knew slavery.

Eventually, slave states established expulsion laws making residency there for free Black people illegal. Some filed petitions to remain near enslaved family members, while others moved West or North. And in the Northeast, many free Blacks formed benevolent organizations such as the Free African Union Society for support and in some cases repatriation.

The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 — and the announcement of emancipation in Texas two years later — allowed millions of enslaved people to join the ranks of already free Black Americans.

Dale Allender is an associate professor at California State University Sacramento.

In the summer of 2019, the New York Times’s 1619 Project burst open a long-overdue conversation about how stories of Black Americans need to be told through the lens of Black Americans themselves. In this tradition, and in celebration of Black History Month, Vox has asked six Black scholars and historians about myths that perpetuate about Black history. Ultimately, understanding Black history is more than learning about the brutality and oppression Black people have endured — it’s about the ways they have fought to survive and thrive in America.

Myth 1: That enslaved people didn’t have money

Enslaved people were money. Their bodies and labor were the capital that fueled the country’s founding and wealth.But many also had money. Enslaved people actively participated in the informal and formal market economy. They saved money earned from overwork, from hiring themselves out, and through independent economic activities with banks, local merchants, and their enslavers. Elizabeth Keckley, a skilled seamstress whose dresses for Abraham Lincoln’s wife are displayed in Smithsonian museums, supported her enslaver’s entire family and still earned enough to pay for her freedom.

Free and enslaved market women dominated local marketplaces, including in Savannah and Charleston, controlling networks that crisscrossed the countryside. They ensured fresh supplies of fruits, vegetables, and eggs for the markets, as well as a steady flow of cash to enslaved people. Whites described these women as “loose” and “disorderly” to criticize their actions as unacceptable behavior for women, but white people of all classes depended on them for survival.

Illustrated portrait of Elizabeth Keckley (1818-1907), a formerly enslaved woman who bought her freedom and became dressmaker for first lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In fact, enslaved people also created financial institutions, especially mutual aid societies. Eliza Allen helped form at least three secret societies for women on her own and nearby plantations in Petersburg, Virginia. One of her societies, Sisters of Usefulness, could have had as many as two to three dozen members. Cities like Baltimore even passed laws against these societies — a sure sign of their popularity. Other cities reluctantly tolerated them, requiring that a white person be present at meetings. Enslaved people, however, found creative ways to conduct their societies under white people’s noses. Often, the treasurer’s ledger listed members by numbers so that, in case of discovery, members’ identities remained protected.

During the tumult of the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of Black people sought refuge behind Union lines. Most were impoverished, but a few managed to bring with them wealth they had stashed under beds, in private chests, and in other hiding places. After the war, Black people fought through the Southern Claims Commission for the return of the wealth Union and Confederate soldiers impounded or outright stole.

Given the resurgence of attention on reparations for slavery and the racial wealth gap, it is important to recall the long history of black people’s engagement with the US economy — not just as property, but as savers, spenders, and small businesspeople.

Shennette Garrett-Scott is an associate professor of history and African American Studies at the University of Mississippi and the author of Banking on Freedom: Black Women in US Finance Before the New Deal.

Myth 2: That Black revolutionary soldiers were patriots

Much is made about how colonial Black Americans — some free, some enslaved — fought during the American Revolution. Black revolutionary soldiers are usually called Black Patriots. But the term Patriot is reserved within revolutionary discourse to refer to the men of the 13 colonies who believed in the ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence: that America should be an independent country, free from Britain. These persons were willing to fight for this cause, join the Continental Army, and, for their sacrifice, are forever considered Patriots. That’s why the term Black Patriot is a myth — it infers that Black and white revolutionary soldiers fought for the same reasons.

Painting of the 1770 Boston Massacre showing Crispus Attucks, one of the leaders of the demonstration and one of the five men killed by the gunfire of the British troops. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

First off, Black revolutionary soldiers did not fight out of love for a country that enslaved and oppressed them. Black revolutionary soldiers were fighting for freedom — not for America, but for themselves and the race as a whole. In fact, the American Revolution is a case study of interest convergence. Interest convergence denotes that within racial states such as the 13 colonies, any progress made for Black people can only be made if that progress also benefits the dominant culture — in this case the liberation of the white colonists of America. In other words, colonists’ enlistment of Black people was not out of some moral mandate, but based on manpower needs to win the war.

In 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia who wanted to quickly end the war, issued a proclamation to free enslaved Black people if they defected from the colonies and fought for the British army. In response, George Washington revised the policy that restricted Black persons (free or enslaved) from joining his Continental Army. His reversal was based in a convergence of his interests: competing with a growing British military, securing the slave economy, and increasing labor needs for the Continental Army. When enslaved persons left the plantation, this caused serious social and economic unrest in the colonies. These defections were encouragement for many white plantation owners to join the Patriotic cause even if they previously held reservations.

Washington also saw other benefits in Black enlistment: White revolutionary soldiers only fought in three- to four-month increments and returned to their farms or plantation, but many Black soldiers could serve longer terms. The need for the Black soldier was essential for the war effort, and the need to win the war became greater than racial or racist ideology.

Interests converged with those of Black revolutionary soldiers as well. Once the American colonies promised freedom, about a quarter of the Continental Army became Black; before that, more Black people defected to the British military for a chance to be free. Black revolutionary soldiers understood the stakes of the war and realized that they could also benefit and leave bondage. As historian Gary Nash has said, the Black revolutionary soldier “can best be understood by realizing that his major loyalty was not to a place, not to a people, but to a principle.”

Black people played a dual role — service with the American forces and fleeing to the British — both for freedom. The notion of the Black Patriot is a misused term. In many ways, while the majority of the whites were fighting in the American Revolution, Black revolutionary soldiers were fighting the “African Americans’ Revolution.”

LaGarrett King is an education professor at the University of Missouri Columbia and the founding director of the Carter Center for K-12 Black History Education.

Myth 3: That Black men were injected with syphilis in the Tuskegee experiment

A dangerous myth that continues to haunt Black Americans is the belief that the government infected 600 Black men in Macon County, Alabama, with syphilis. This myth has created generations of African Americans with a healthy distrust of the American medical profession. While these men weren’t injected with syphilis, their story does illuminate an important truth: America’s medical past is steeped in racialized terror and the exploitation of Black bodies.The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male emerged from a study group formed in 1932 connected with the venereal disease section of the US Public Health Service. The purpose of the experiment was to test the impact of syphilis untreated and was conducted at what is now Tuskegee University, a historically Black university in Macon County, Alabama.

The 600 Black men in the experiment were not given syphilis. Instead, 399 men already had stages of the disease, and the 201 who did not served as a control group. Both groups were withheld from treatment of any kind for the 40 years they were observed. The men were subjected to humiliating and often painfully invasive tests and experiments including spinal taps.

Deemed uneducated and impoverished sharecroppers, these men were lured by free medical examinations, hot meals, free treatment for minor injuries, rides to and from the hospital, and guaranteed burial stipends (up to $50) to be paid to their survivors. The study also did not occur in total secret, and several African American health workers and educators associated with the Tuskegee Institute assisted in the study.

By the end of the study in the summer of 1972, after a whistleblower exposed the story in national headlines, only 74 of the test subjects were still alive. From the original 399 infected men, 28 had died of syphilis, 100 others from related complications. Forty of the men’s wives had been infected, and an estimated 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis.

As a result of the case, the US Department of Health and Human Services established the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) in 1974 to oversee clinical trials. The case also solidified the idea of African Americans being cast and used as medical guinea pigs.

An unfortunate side effect of both the truth of medical racism and the myth of syphilis injection, however, is it tangibly reinforces the inability to place trust in the medical system for some African Americans who may not choose to seek out assistance, and as a result put themselves in danger.

Sowande Mustakeem is an associate professor of History and African & African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis.

Myth 4: That Black people in early Jim Crow America didn’t fight back

It is well-known that African Americans faced the constant threat of ritualistic public executions by white mobs, unpunished attacks by individuals, and police brutality in Jim Crow America. But how they responded to this is a myth that persists. In an effort to find lawful ways to address such events, some Black people made legalistic appeals to convince police and civic leaders their rights and lives should be protected. Yet the crushing weight of a hostile criminal justice system and the rigidity of the color line often muted those petitions, leaving Black people vulnerable to more mistreatment and murder.

An unidentified member of the Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party stands guard with a shotgun on December 11, 1969. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In the face of this violence, some African Americans prepared themselves physically and psychologically for the abuse they expected — and they fought back. Distressed by public racial violence and unwilling to accept it, many adhered to emerging ideologies of outright rebellion, particularly after the turn of the 20th century and the emergence of the “New Negro.” Urban, more educated than their parents, and often trained militarily, a generation coming of age following World War I sought to secure themselves in the only ways left. Many believed, as Marcus Garvey once told a Harlem audience, that Black folks would never gain freedom “by praying for it.”

For New Negroes, the comparatively tame efforts of groups like the NAACP were not urgent enough. Most notably, they defended themselves fiercely nationwide during the bloodshed of the Red Summer of 1919 when whites attacked African Americans in multiple cities across the country. Whites may have initiated most race riots in the early Jim Crow era, but some also happened as Black people rejected the limitations placed on their life, leisure, and labor, and when they refused to fold under the weight of white supremacy. The magnitude of racial and state violence often came down upon Black people who defended themselves from police and citizens, but that did not stop some from sparking personal and collective insurrections.

Douglas J. Flowe is an assistant professor of history at Washington University in St. Louis.

Myth 5: That crack in the “ghetto” was the largest drug crisis of the 1980s

The bodies of people of color have a pernicious history of total exploitation and criminalization in the US. Like total war, total exploitation enlists and mobilizes the resources of mainstream society to obliterate the resources and infrastructure of the vulnerable. This has been done to Black people through a robust prison industrial complex that feeds on their vilification, incarceration, disenfranchisement, and erasure. And the crack epidemic of the late 1980s and ’90s is a clear example of this cycle.Even though more white people reported using crack more than Black people in a 1991 National Institute on Drug Abuse survey, Black people were sentenced for crack offenses eight times more than whites. Meanwhile, there was a corresponding cocaine epidemic in white suburbs and college campuses that compelled the US to install harsher penalties for crack than for cocaine. For example, in 1986, before the enactment of federal mandatory minimum sentencing for crack cocaine offenses, the average federal drug sentence for African Americans was 11 percent higher than for whites. Four years later, the average federal drug sentence for African Americans was 49 percent higher.

Even through the ’90s and beyond, the media and supposed liberal allies, like Hillary Clinton, designated Black children and teens as drug-dealing “superpredators” to mostly white audiences. The criminalization of people of color during the crack epidemic made mainstream white Americans comfortable knowing that this was a contained black-on-black problem.

It also left white America unprepared to deal with the approach of the opioid epidemic, which is often a white-on-white crime whose dealers will evade prison (see: the Sacklers, the billionaire family behind Oxycontin who has served no jail time; and Johnson & Johnson, which got a $107 million break in fines when it was found liable for marketing practices that led to thousands of overdose deaths). Unlike Black Americans who are sent to prison, these white dealers retain their right to vote, lobby, and hold on to their wealth.

Jason Allen is a public historian and facilitator at xCHANGEs, a cultural diversity and inclusion training consultancy.

Myth 6: That all Black people were enslaved until emancipation

One of the biggest myths about the history of Black people in America is that all were enslaved until the Emancipation Proclamation, or Juneteenth Day.In reality, free Black and Black-white biracial communities existed in states such as Louisiana, Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio well before abolition. For example, Anthony Johnson, named Antonio the Negro on the 1625 census, was listed on this document as a servant. By 1640, he and his wife owned and managed a large plot of land in Virginia.

A group of free African Americans in an unknown city, circa 1860. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Some enslaved Africans were able to sell their labor or craftsmanship to others, thereby earning enough money to purchase their freedom. Such was the case for Richard Allen, who paid for his freedom in 1786 and co-founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church less than a decade later. After the American Revolutionary War, Robert Carter III committed the largest manumission — or freeing of slaves — before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, freeing his 100 enslaved Africans.

Not all emancipations were large. Individuals or families were sometimes freed upon the death of their enslaver and his family. And many escaped and lived free in the North or in Canada. Finally, there were generations of children born in free Black and biracial communities, many who never knew slavery.

Eventually, slave states established expulsion laws making residency there for free Black people illegal. Some filed petitions to remain near enslaved family members, while others moved West or North. And in the Northeast, many free Blacks formed benevolent organizations such as the Free African Union Society for support and in some cases repatriation.

The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 — and the announcement of emancipation in Texas two years later — allowed millions of enslaved people to join the ranks of already free Black Americans.

Dale Allender is an associate professor at California State University Sacramento.

Black Americans are leaving their homes to start their own all-Black communities

It’s their escape, they said, from the everyday racism that feels like a part of life in the United States.

7 Things To Know About Hereafter Farms: Black Americans Pull Resources To Collectively Buy And Develop Land In Georgia

7 Things To Know About Hereafter Farms: Black Americans Pull Resources To Collectively Buy And Develop Land In Georgia

Hereafter Developments

Sustainability | Accessibility | Innovation | Farm | Live | Work Hereafter Farms

Full thread below:

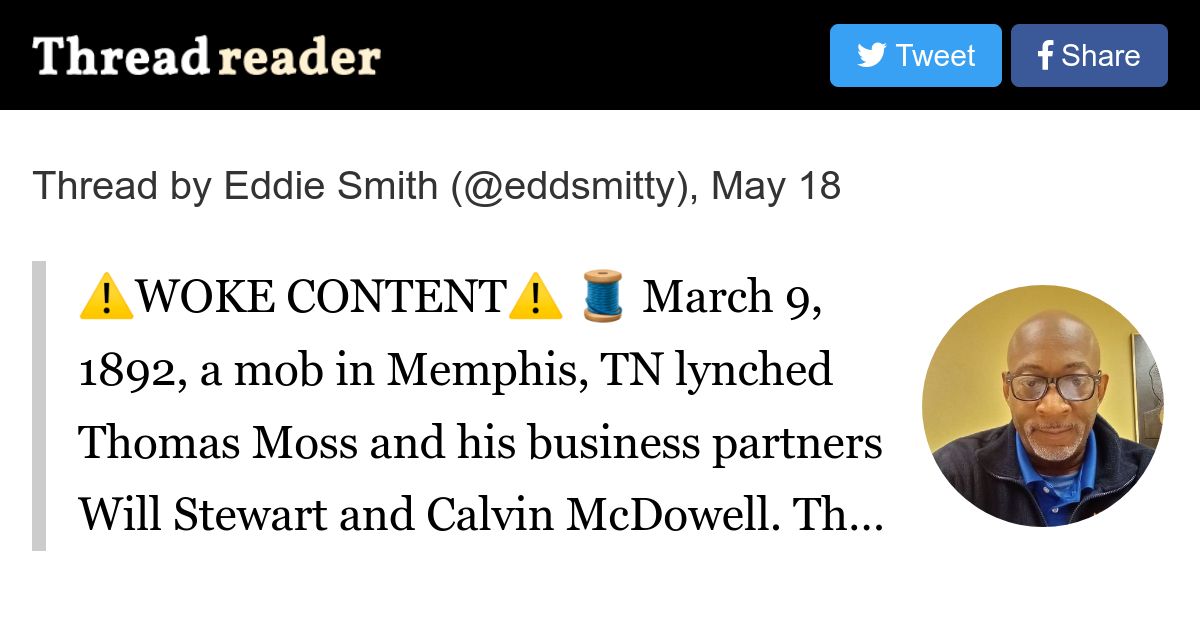

Thread by @eddsmitty on Thread Reader App

@eddsmitty: ⚠️WOKE CONTENT⚠️ March 9, 1892, a mob in Memphis, TN lynched Thomas Moss and his business partners Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell. This is historically referred to as The People's Grocery lynching. T...…

This is so sad.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 63

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 139

- Replies

- 26K

- Views

- 171K