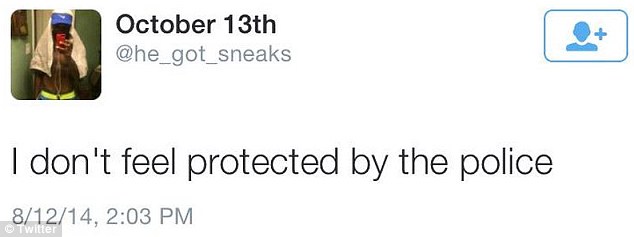

Black & Hispanic Men- MURDERED by the NEW YORK POLICE- "Dred Scott" Lives

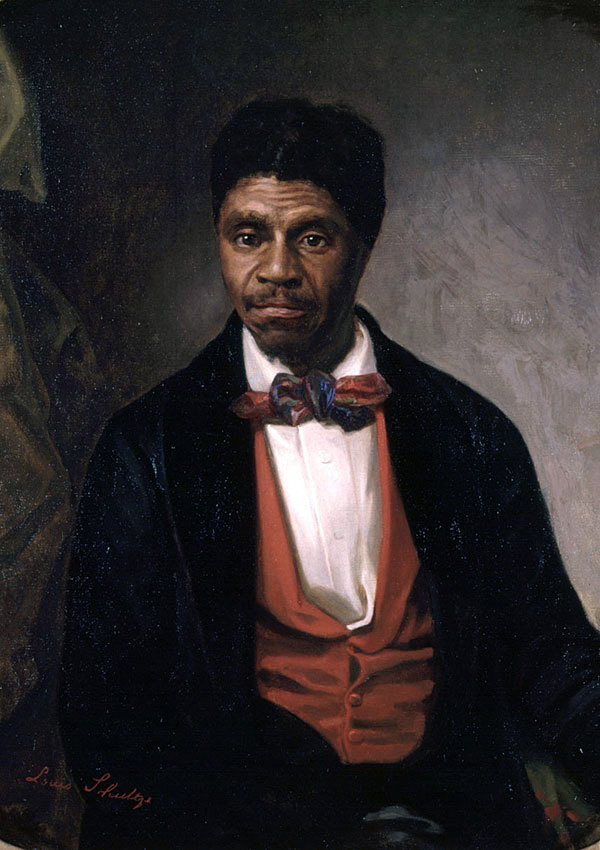

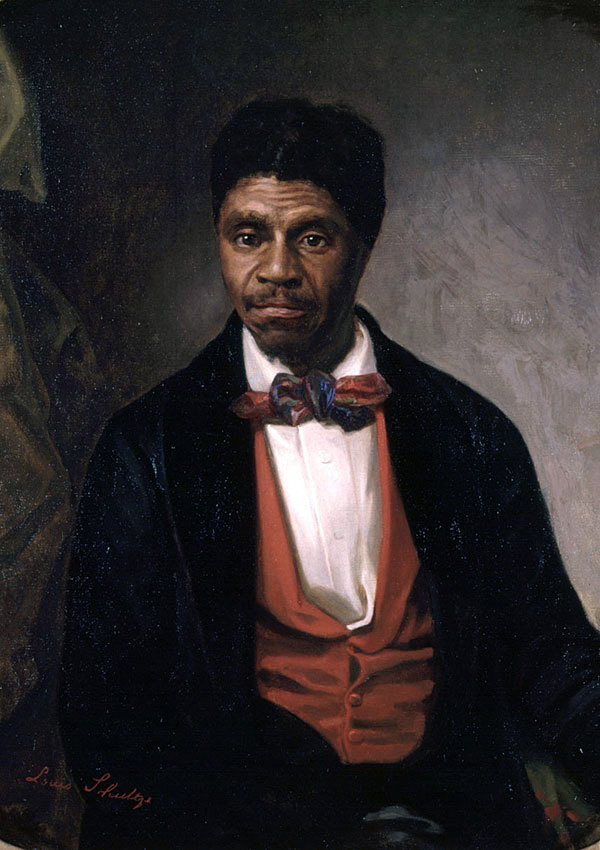

Dred Scott

The Supreme Court DRED SCOTT decision of 1857 viewed all blacks as "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

Although the "Dred Scott" decision was erased by the 13th and 14th amendments to the U.S. constitution, legalized white supremacy continued via "Jim Crow" laws until 1965. Todays 21st century police departments, with the consent of white legislators apply "Dred Scott" rules when policing Black & Brown communities

Fatal Police Encounters in New York City

Compiled by EBA HAMID and BENJAMIN MUELLER DEC. 3, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/nyregion/fatal-police-encounters-in-new-york-city.html

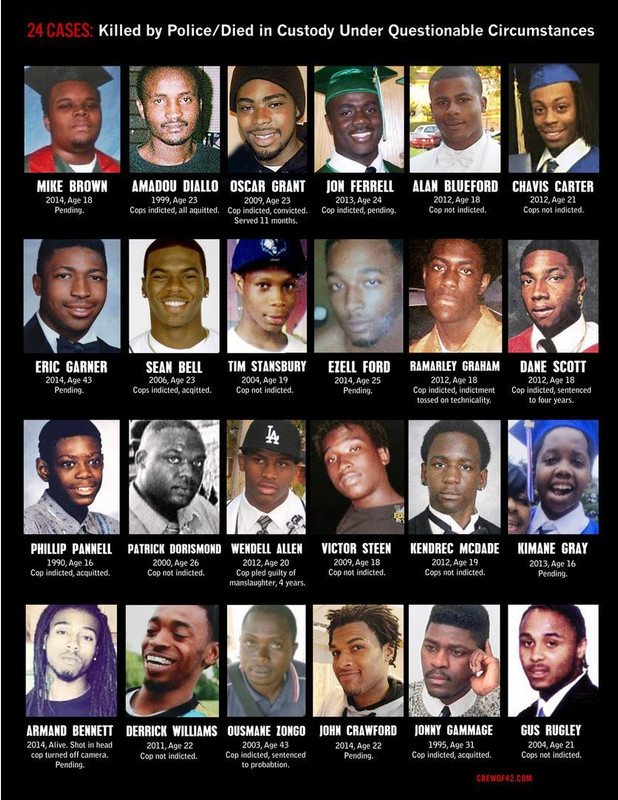

Some of the most notable deaths since 1990 involving New York Police Department officers. Most did not lead to criminal charges; even fewer resulted in convictions. Related Article

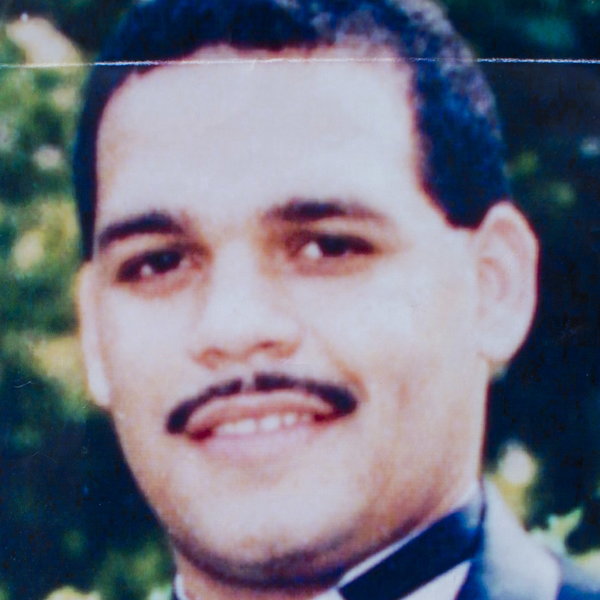

Jose (Kiko) Garcia

July 3, 1992

During a struggle with police officers in the lobby of an apartment building, Mr. Garcia, a 23-year-old Dominican immigrant who the police said was carrying a revolver, was shot twice by Officer Michael O’Keefe.

What happened: Later that year, a grand jury cleared Officer O’Keefe, supporting the officer’s assertion that Mr. Garcia reached for a gun before he was shot.

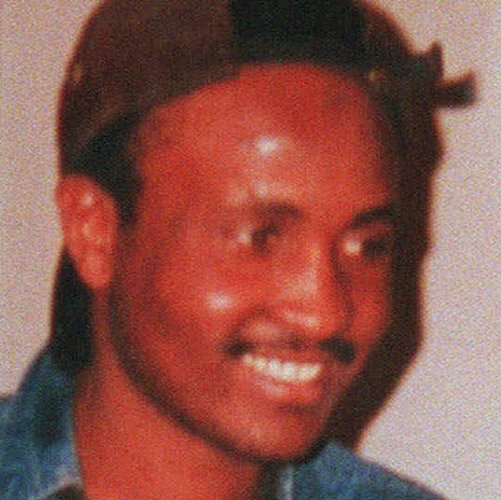

Ernest Sayon

April 29, 1994

Mr. Sayon, 22, was standing outside a Staten Island housing complex when police officers on an anti-drug patrol tried to arrest him. Mr. Sayon suffocated because of pressure on his back, chest and neck while he was handcuffed on the ground.

What happened: A grand jury declined to file criminal charges against any of the three police officers involved, apparently concluding that the officers had used reasonable force in subduing Mr. Sayon.

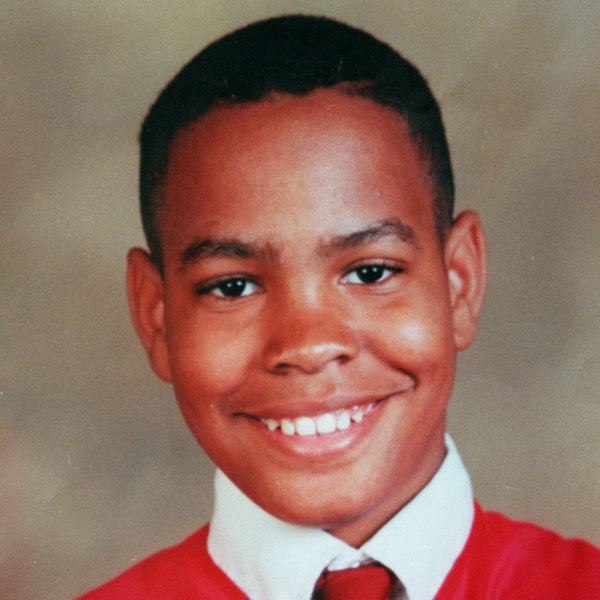

Nicholas Heyward Jr.

Sept. 27, 1994

Nicholas, 13, was playing cops and robbers with friends in a Gowanus Houses building stairwell when Officer Brian George, mistaking the teenager’s toy rifle for a real gun, shot him to death.

What happened: The Brooklyn district attorney decided not to present the case to a grand jury, saying the real culprit was an authentic-looking toy gun.

Anthony Baez

Dec. 22, 1994

Mr. Baez, 29, a security guard, was playing football outside his mother’s Bronx home when a stray toss landed on a police car. Mr. Baez died after an officer applied a chokehold while trying to arrest him.

What happened: Francis X. Livoti, who had been dismissed by the force for using an illegal chokehold, was convicted on federal civil rights charges and sentenced to seven and a half years in prison, two years after he won acquittal in a state trial.

Amadou Diallo

Feb. 4, 1999

Mr. Diallo, a 22-year-old immigrant from Guinea, was killed by four officers who fired 41 times in the vestibule of his apartment building in the Bronx. They said he seemed to have a gun, but he was unarmed.

What happened: In February 2000, after a tense and racially charged trial, all four officers, who were white, were acquitted of second-degree murder and other charges, fueling protests.

The city agreed to pay the family $3 million.

Patrick Dorismond

March 16, 2000

Mr. Dorismond, 26, an unarmed black security guard, was shot dead by an undercover narcotics detective in a brawl in front of a bar in Midtown Manhattan, after Mr. Dorismond became offended when the detective asked him if he had any crack cocaine.

What happened: By late July, a grand jury declined to file criminal charges against the detective, Anthony Vasquez, concluding that the shooting of Mr. Dorismond was not intentional.

The city agreed to pay $2.25 million to his family.

Ousmane Zongo

May 23, 2003

Mr. Zongo, 43, an art restorer, was shot and killed by a police officer during a raid at a Chelsea warehouse that the police believed was the base of a CD counterfeiting operation.

What happened: In 2005, Officer Bryan A. Conroy was convicted at the second of two trials and sentenced to probation. The judge placed the blame for the killing primarily on the poor training and supervision by the Police Department.

The city agreed to pay the family $3 million.

Timothy Stansbury Jr.

Jan. 24, 2004

Mr. Stansbury, 19, a high school student, was about to take a rooftop shortcut to a party when he was fatally shot by Officer Richard S. Neri Jr., who was patrolling the roof.

What happened: A grand jury decided not to indict Officer Neri. In December 2006, he was suspended without pay for 30 days, permanently stripped of his gun, and reassigned to a property clerk’s office.

The city agreed to pay the Stansbury family $2 million.

Sean Bell

Nov. 25, 2006

Five detectives fired 50 times into a car occupied by Mr. Bell, 23, and two others after a confrontation outside a Queens club on Mr. Bell’s wedding day. He was killed.

What happened: After a heated seven-week nonjury trial in 2008, the judge found Detectives Gescard F. Isnora, Michael Oliver and Marc Cooper not guilty of all charges, which included manslaughter and assault.

In 2012, Detective Isnora was fired, and Detectives Cooper and Oliver, along with a supervisor, were forced to resign.

Ramarley Graham

Feb. 2, 2012

Mr. Graham, 18, was shot and killed by Richard Haste, a police officer, in the bathroom of his Bronx apartment after being pursued into his home by a team of officers from a plainclothes street narcotics unit. Mr. Graham was unarmed.

What happened: A grand jury voted to indict Officer Haste on charges of first- and second-degree manslaughter, but a judge dismissed the indictment a year later. Prosecutors sought a new indictment. In August 2013, a grand jury decided not to bring charges in the case.

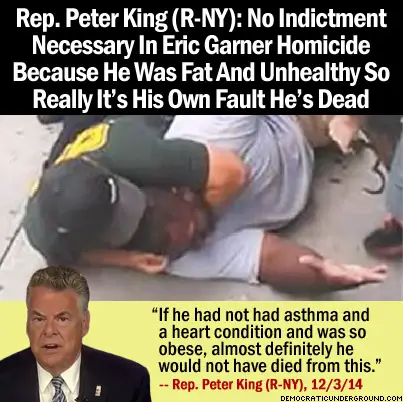

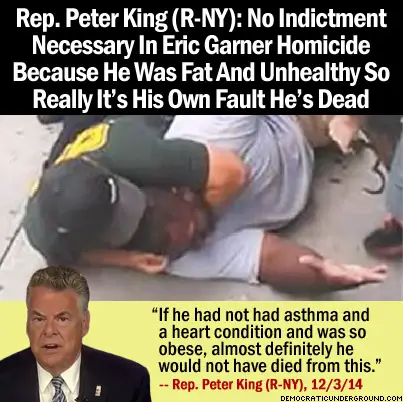

Eric Garner

July 17, 2014

Mr. Garner, 43, died after Officer Daniel Pantaleo restrained him using a chokehold, a maneuver that was banned by the New York Police Department more than 20 years ago. The officers were trying to arrest Mr. Garner, whose death was attributed in part to the chokehold, on charges of illegally selling cigarettes.

What happened: A grand jury, impaneled in September by the Staten Island district attorney, voted not to bring criminal charges against Officer Pantaleo.

Akai Gurley

Nov. 20, 2014

Mr. Gurley, 28, was entering the stairwell of a Brooklyn housing project with his girlfriend when Officer Peter Liang, standing 14 steps above him, shot Mr. Gurley in the chest. The police described the fatal shooting of Mr. Gurley, who was unarmed, as an accident.

What happened: The episode is the subject of investigations by the Police Department and the Brooklyn district attorney.

<hr noshade color="#333333" size="4"></hr>

The Perfect-Victim Pitfall

Michael Brown, and Now Eric Garner

<img src="http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2008/04/28/opinion/blow.portrait.190.jpg" width="130">

by Charles M. Blow | December 3, 2014 | http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/04/opinion/charles-blow-first-michael-brown-now-eric-garner.html

At some point between the moment a Missouri grand jury refused to indict a police officer who had shot and killed Michael Brown on a Ferguson street and the moment a New York grand jury refused to indict a police officer who choked and killed Eric Garner on a Staten Island sidewalk — on video, as he struggled to utter the words, “I can’t breathe!” — a counternarrative to this nation’s calls for change has taken shape.

This narrative paints the police as under siege and unfairly maligned while it admonishes — and, in some cases, excoriates — those demanding changes in the wake of the Ferguson shooting. (Those calling for change now include the president of the United States and the United States attorney general, I might add.)

The argument is that this is not a perfect case, because Brown — and, one would assume, now Garner — isn’t a perfect victim and the protesters haven’t all been perfectly civil, so therefore any movement to counter black oppression that flows from the case is inherently flawed. But this is ridiculous and reductive, because it fails to acknowledge that the whole system is imperfect and rife with flaws. We don’t need to identify angels and demons to understand that inequity is hell.

The Mike-or-Eric-as-faces-of-black-oppression arguments swing too wide, and they miss. So does the protesters-as-movement-killers argument.

The responses so far have only partly been specific to a particular case. Much of it is about something larger and more general: racial inequality and criminal justice. People want to be assured of equal application of justice and equal — and appropriate — use of police force, and to know that all lives are equally valued.

The data suggests that, in the nation as a whole, that isn’t so. Racial profiling is real. Disparate treatment of black and brown men by police officers is real. Grotesquely disproportionate numbers of killings of black men by the police are real.

No one denies that police officers have hard jobs, but they volunteer to enter that line of work. There is no draft. So these disparities cannot go unaddressed and uncorrected. To be held in high esteem you must also be held to a higher standard.

And no one denies that high-crime neighborhoods disproportionately overlap with minority neighborhoods. But the intersections don’t stop there. Concentrated poverty plays a consequential role. So does the school-to-prison pipeline. So do the scars of historical oppression. In fact, these and other factors intersect to such a degree that trying to separate any one — most often, the racial one — from the rest is bound to render a flimsy argument based on the fallacy of discrete factors.

Yet people continue to make such arguments, which can usually be distilled to some variation of this: Black dysfunction is mostly or even solely the result of black pathology. This argument is racist at its core because it rests too heavily on choice and too lightly on context. If you scratch it, what oozes out reeks of race-informed cultural decay or even genetic deficiency and predisposition, as if America is not the progenitor — the great-grandmother — of African-American violence.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

And yes, racist is the word that we must use. Racism doesn’t require the presence of malice, only the presence of bias and ignorance, willful or otherwise. It doesn’t even require more than one race. There are plenty of members of aggrieved groups who are part of the self-flagellation industrial complex. They make a name (and a profit) saying inflammatory things about their own groups, things that are full of sting but lack context, things that others will say only behind tightly shut doors. These are often people who’ve “made it” and look down their noses with be-more-like-me disdain at those who haven’t, as if success were merely a result of a collection of choices and not also of a confluence of circumstances.

Today, too many people are gun-shy about using the word racism, lest they themselves be called race-baiters. So we are witnessing an assault on the concept of racism, an attempt to erase legitimate discussion and grievance by degrading the language: Eliminate the word and you elude the charge.

By endlessly claiming that the word is overused as an attack, the overuse, through rhetorical sleight of hand, is amplified in the dismissal. The word is snatched from its serious scientific and sociological context and redefined simply as a weapon of argumentation, the hand grenade you toss under the table to blow things up and halt the conversation when things get too “honest” or “uncomfortable.”

But people will not fall for that chicanery. The language will survive. The concept will not be corrupted. Racism is a real thing, not because the “racial grievance industry” refuses to release it, but because society has failed to eradicate it.

Racism is interpersonal and structural; it is current and historical; it is explicit and implicit; it is articulated and silent.

Biases are pervasive, but can also be spectral: moving in and out of consideration with little or no notice, without leaving a trace, even without our own awareness. Sometimes the only way to see bias is in the aggregate, to stop staring so hard at a data point and step back so that you can see the data set. Only then can you detect the trails in the dust. Only then can the data do battle with denial.

I would love to live in a world where that wasn’t the case. Even more, I would love my children to inherit a world where that wasn’t the case, where the margin for error for them was the same as the margin for error for everyone else’s children, where I could rest assured that police treatment would be unbiased. But I don’t. Reality doesn’t bend under the weight of wishes. Truth doesn’t grow dim because we squint.

We must acknowledge — with eyes and minds wide open — the world as it is if we want to change it.

The activism that followed Ferguson and that is likely to be intensified by what happened in New York isn’t about making a martyr of “Big Mike” or “Big E” as much as it is about making the most of a moment, counternarratives notwithstanding.

In this most trying of moments, black men, supported by the people who understand their plight and feel their pain, are saying to the police culture of America, “We can’t breathe!”

<hr noshade color="#0000FF" size="8"></hr>

Dred Scott

The Supreme Court DRED SCOTT decision of 1857 viewed all blacks as "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

Although the "Dred Scott" decision was erased by the 13th and 14th amendments to the U.S. constitution, legalized white supremacy continued via "Jim Crow" laws until 1965. Todays 21st century police departments, with the consent of white legislators apply "Dred Scott" rules when policing Black & Brown communities

Fatal Police Encounters in New York City

Compiled by EBA HAMID and BENJAMIN MUELLER DEC. 3, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/nyregion/fatal-police-encounters-in-new-york-city.html

Some of the most notable deaths since 1990 involving New York Police Department officers. Most did not lead to criminal charges; even fewer resulted in convictions. Related Article

Jose (Kiko) Garcia

July 3, 1992

During a struggle with police officers in the lobby of an apartment building, Mr. Garcia, a 23-year-old Dominican immigrant who the police said was carrying a revolver, was shot twice by Officer Michael O’Keefe.

What happened: Later that year, a grand jury cleared Officer O’Keefe, supporting the officer’s assertion that Mr. Garcia reached for a gun before he was shot.

Ernest Sayon

April 29, 1994

Mr. Sayon, 22, was standing outside a Staten Island housing complex when police officers on an anti-drug patrol tried to arrest him. Mr. Sayon suffocated because of pressure on his back, chest and neck while he was handcuffed on the ground.

What happened: A grand jury declined to file criminal charges against any of the three police officers involved, apparently concluding that the officers had used reasonable force in subduing Mr. Sayon.

Nicholas Heyward Jr.

Sept. 27, 1994

Nicholas, 13, was playing cops and robbers with friends in a Gowanus Houses building stairwell when Officer Brian George, mistaking the teenager’s toy rifle for a real gun, shot him to death.

What happened: The Brooklyn district attorney decided not to present the case to a grand jury, saying the real culprit was an authentic-looking toy gun.

Anthony Baez

Dec. 22, 1994

Mr. Baez, 29, a security guard, was playing football outside his mother’s Bronx home when a stray toss landed on a police car. Mr. Baez died after an officer applied a chokehold while trying to arrest him.

What happened: Francis X. Livoti, who had been dismissed by the force for using an illegal chokehold, was convicted on federal civil rights charges and sentenced to seven and a half years in prison, two years after he won acquittal in a state trial.

Amadou Diallo

Feb. 4, 1999

Mr. Diallo, a 22-year-old immigrant from Guinea, was killed by four officers who fired 41 times in the vestibule of his apartment building in the Bronx. They said he seemed to have a gun, but he was unarmed.

What happened: In February 2000, after a tense and racially charged trial, all four officers, who were white, were acquitted of second-degree murder and other charges, fueling protests.

The city agreed to pay the family $3 million.

Patrick Dorismond

March 16, 2000

Mr. Dorismond, 26, an unarmed black security guard, was shot dead by an undercover narcotics detective in a brawl in front of a bar in Midtown Manhattan, after Mr. Dorismond became offended when the detective asked him if he had any crack cocaine.

What happened: By late July, a grand jury declined to file criminal charges against the detective, Anthony Vasquez, concluding that the shooting of Mr. Dorismond was not intentional.

The city agreed to pay $2.25 million to his family.

Ousmane Zongo

May 23, 2003

Mr. Zongo, 43, an art restorer, was shot and killed by a police officer during a raid at a Chelsea warehouse that the police believed was the base of a CD counterfeiting operation.

What happened: In 2005, Officer Bryan A. Conroy was convicted at the second of two trials and sentenced to probation. The judge placed the blame for the killing primarily on the poor training and supervision by the Police Department.

The city agreed to pay the family $3 million.

Timothy Stansbury Jr.

Jan. 24, 2004

Mr. Stansbury, 19, a high school student, was about to take a rooftop shortcut to a party when he was fatally shot by Officer Richard S. Neri Jr., who was patrolling the roof.

What happened: A grand jury decided not to indict Officer Neri. In December 2006, he was suspended without pay for 30 days, permanently stripped of his gun, and reassigned to a property clerk’s office.

The city agreed to pay the Stansbury family $2 million.

Sean Bell

Nov. 25, 2006

Five detectives fired 50 times into a car occupied by Mr. Bell, 23, and two others after a confrontation outside a Queens club on Mr. Bell’s wedding day. He was killed.

What happened: After a heated seven-week nonjury trial in 2008, the judge found Detectives Gescard F. Isnora, Michael Oliver and Marc Cooper not guilty of all charges, which included manslaughter and assault.

In 2012, Detective Isnora was fired, and Detectives Cooper and Oliver, along with a supervisor, were forced to resign.

Ramarley Graham

Feb. 2, 2012

Mr. Graham, 18, was shot and killed by Richard Haste, a police officer, in the bathroom of his Bronx apartment after being pursued into his home by a team of officers from a plainclothes street narcotics unit. Mr. Graham was unarmed.

What happened: A grand jury voted to indict Officer Haste on charges of first- and second-degree manslaughter, but a judge dismissed the indictment a year later. Prosecutors sought a new indictment. In August 2013, a grand jury decided not to bring charges in the case.

Eric Garner

July 17, 2014

Mr. Garner, 43, died after Officer Daniel Pantaleo restrained him using a chokehold, a maneuver that was banned by the New York Police Department more than 20 years ago. The officers were trying to arrest Mr. Garner, whose death was attributed in part to the chokehold, on charges of illegally selling cigarettes.

What happened: A grand jury, impaneled in September by the Staten Island district attorney, voted not to bring criminal charges against Officer Pantaleo.

Akai Gurley

Nov. 20, 2014

Mr. Gurley, 28, was entering the stairwell of a Brooklyn housing project with his girlfriend when Officer Peter Liang, standing 14 steps above him, shot Mr. Gurley in the chest. The police described the fatal shooting of Mr. Gurley, who was unarmed, as an accident.

What happened: The episode is the subject of investigations by the Police Department and the Brooklyn district attorney.

<hr noshade color="#333333" size="4"></hr>

The Perfect-Victim Pitfall

Michael Brown, and Now Eric Garner

<img src="http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2008/04/28/opinion/blow.portrait.190.jpg" width="130">

by Charles M. Blow | December 3, 2014 | http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/04/opinion/charles-blow-first-michael-brown-now-eric-garner.html

At some point between the moment a Missouri grand jury refused to indict a police officer who had shot and killed Michael Brown on a Ferguson street and the moment a New York grand jury refused to indict a police officer who choked and killed Eric Garner on a Staten Island sidewalk — on video, as he struggled to utter the words, “I can’t breathe!” — a counternarrative to this nation’s calls for change has taken shape.

This narrative paints the police as under siege and unfairly maligned while it admonishes — and, in some cases, excoriates — those demanding changes in the wake of the Ferguson shooting. (Those calling for change now include the president of the United States and the United States attorney general, I might add.)

The argument is that this is not a perfect case, because Brown — and, one would assume, now Garner — isn’t a perfect victim and the protesters haven’t all been perfectly civil, so therefore any movement to counter black oppression that flows from the case is inherently flawed. But this is ridiculous and reductive, because it fails to acknowledge that the whole system is imperfect and rife with flaws. We don’t need to identify angels and demons to understand that inequity is hell.

The Mike-or-Eric-as-faces-of-black-oppression arguments swing too wide, and they miss. So does the protesters-as-movement-killers argument.

The responses so far have only partly been specific to a particular case. Much of it is about something larger and more general: racial inequality and criminal justice. People want to be assured of equal application of justice and equal — and appropriate — use of police force, and to know that all lives are equally valued.

The data suggests that, in the nation as a whole, that isn’t so. Racial profiling is real. Disparate treatment of black and brown men by police officers is real. Grotesquely disproportionate numbers of killings of black men by the police are real.

No one denies that police officers have hard jobs, but they volunteer to enter that line of work. There is no draft. So these disparities cannot go unaddressed and uncorrected. To be held in high esteem you must also be held to a higher standard.

And no one denies that high-crime neighborhoods disproportionately overlap with minority neighborhoods. But the intersections don’t stop there. Concentrated poverty plays a consequential role. So does the school-to-prison pipeline. So do the scars of historical oppression. In fact, these and other factors intersect to such a degree that trying to separate any one — most often, the racial one — from the rest is bound to render a flimsy argument based on the fallacy of discrete factors.

Yet people continue to make such arguments, which can usually be distilled to some variation of this: Black dysfunction is mostly or even solely the result of black pathology. This argument is racist at its core because it rests too heavily on choice and too lightly on context. If you scratch it, what oozes out reeks of race-informed cultural decay or even genetic deficiency and predisposition, as if America is not the progenitor — the great-grandmother — of African-American violence.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

And yes, racist is the word that we must use. Racism doesn’t require the presence of malice, only the presence of bias and ignorance, willful or otherwise. It doesn’t even require more than one race. There are plenty of members of aggrieved groups who are part of the self-flagellation industrial complex. They make a name (and a profit) saying inflammatory things about their own groups, things that are full of sting but lack context, things that others will say only behind tightly shut doors. These are often people who’ve “made it” and look down their noses with be-more-like-me disdain at those who haven’t, as if success were merely a result of a collection of choices and not also of a confluence of circumstances.

Today, too many people are gun-shy about using the word racism, lest they themselves be called race-baiters. So we are witnessing an assault on the concept of racism, an attempt to erase legitimate discussion and grievance by degrading the language: Eliminate the word and you elude the charge.

By endlessly claiming that the word is overused as an attack, the overuse, through rhetorical sleight of hand, is amplified in the dismissal. The word is snatched from its serious scientific and sociological context and redefined simply as a weapon of argumentation, the hand grenade you toss under the table to blow things up and halt the conversation when things get too “honest” or “uncomfortable.”

But people will not fall for that chicanery. The language will survive. The concept will not be corrupted. Racism is a real thing, not because the “racial grievance industry” refuses to release it, but because society has failed to eradicate it.

Racism is interpersonal and structural; it is current and historical; it is explicit and implicit; it is articulated and silent.

Biases are pervasive, but can also be spectral: moving in and out of consideration with little or no notice, without leaving a trace, even without our own awareness. Sometimes the only way to see bias is in the aggregate, to stop staring so hard at a data point and step back so that you can see the data set. Only then can you detect the trails in the dust. Only then can the data do battle with denial.

I would love to live in a world where that wasn’t the case. Even more, I would love my children to inherit a world where that wasn’t the case, where the margin for error for them was the same as the margin for error for everyone else’s children, where I could rest assured that police treatment would be unbiased. But I don’t. Reality doesn’t bend under the weight of wishes. Truth doesn’t grow dim because we squint.

We must acknowledge — with eyes and minds wide open — the world as it is if we want to change it.

The activism that followed Ferguson and that is likely to be intensified by what happened in New York isn’t about making a martyr of “Big Mike” or “Big E” as much as it is about making the most of a moment, counternarratives notwithstanding.

In this most trying of moments, black men, supported by the people who understand their plight and feel their pain, are saying to the police culture of America, “We can’t breathe!”

<hr noshade color="#0000FF" size="8"></hr>

Last edited:

no allegation that the young man posed a threat of some kind to the officers or someone else . . .

no allegation that the young man posed a threat of some kind to the officers or someone else . . . WTF was going on here ???

WTF was going on here ???