This thread will be about drugs legal and illegal!! We're going to start at the so called beginning and work our way to the present. Some articles are going to be long reads, sum short and sum video!! At the end, hopefully we will be able to connect sum dots and figure out whats really going on!!

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

WAR ON DRUGS or is it a WAR ON US???

- Thread starter roots69

- Start date

Hemp History Timeline

Through the Years

1606: French Botanist Louis Hebert planted the first hemp crop in North America in Port Royal, Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia).

1770s: In Virginia (and some other colonies), farmers are required by law to grow hemp.

1776: The U.S. Declaration of Independence is drafted on hemp paper.

1797: The U.S.S. Constitution is outfitted with hemp sails and rigging.

1790s: U.S. founding fathers George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams grow hemp.

1800s: Upper Canada’s Lieutenant Governor, on behalf of the King of England, distributed free hemp seed to Canadian farmers.

1840s: Abraham Lincoln uses hemp oil to fuel his household lamps.

1890s: USDA Chief Botanist begins growing hemp varieties at the current site of the Pentagon and continues until the 1940s.

1916: USDA (Bulletin No. 404) shows that hemp produces four times more paper per acres than trees!

1928: The Canadian House of Commons encourages Canadian farmers to grow hemp.

1937: Hemp was strictly regulated by the Marijuana Tax Act, largely due to confusion with other kinds of cannabis. Hemp could only be grown through specially issued government tax stamps, making any type of possession/transfer without a tax stamp illegal.

1938: Popular Mechanics Magazine determines that over 25,000 different products could be made from hemp and declares hemp as the “New Billion Dollar Crop.”

1942: Henry Ford builds an experimental car with panels partially made from hemp fibre. That same year, without any changes to the Marijuana Tax Act, the United States Army used their Hemp for Victory campaign to urge farmers to grow hemp to support them in World War II. Between 1942 and 1945, the U.S. cultivated 400,000 acres of hemp for their war effort.

1957: Once World War II had ended, demand for hemp decreased and so did hemp production. The last commercial hemp fields were planted in 1957 in Wisconsin.

1970: The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act went into effect abolishing the taxation approach of the Marijuana Tax Act, effectively making all cultivation of cannabis illegal by setting a zero tolerance for THC.

1992: Manitoba Harvest Hemp Foods’ Co-Founder Martin begins importing and manufacturing handmade hemp items.

1993: Martin conducts research and establishes important relationships with farmers and government leaders.

1994: Martin organizes industrial hemp events and helps establish the University of Manitoba Hemp Awareness Committee (UMHAC).

1995: UMHAC becomes the Manitoba Hemp Alliance and lobbies the Government of Manitoba for assistance in advancing hemp agriculture. Harry Enns, Manitoba’s Agriculture Minister at the time, approves a funding grant and offers the services of a New Crops Agronomist. In less than nine months, the first hemp crops are harvested.

1996: Hemp trial results indicate that hemp can be grown with undetectable amounts (less than 0.003%) of THC.

1998: Industrial hemp is legalized in Canada! Hemp foods begin exporting to the U.S.

1999: North Dakota, Minnesota, and Hawaii legalize the growing of industrial hemp at state level, but federally, industrial hemp is still illegal to grow in the U.S.

2001: The United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) begins a campaign to make sales of all hemp foods illegal in the U.S. The Hemp Industries Association (HIA), Dr. Bronner’s, and other companies that offer hemp products take legal action against the DEA.

2004: Ninth Circuit Court rules in favour of the Hemp Industries Association and protects sales of hemp foods and body care products in the U.S.

2006: New innovations in hemp processing and new hemp products hit the market.

2010: Hemp Industries Association estimates $419 million in U.S. retail sales of hemp products.

2012: A record setting year in terms of the number of industrial hemp acres seeded in Canada. The number of acres is nine times the acres seeded in 1998 when industrial hemp was legalized.

2013: Annual U.S. retail sales of hemp products exceeds $581 million. Industrial hemp celebrates fifteen years of legalization in Canada.

2014: U.S. President Barack Obama signs Federal Farm Bill with hemp amendment, allowing states with hemp legislation in place to grow hemp for research purposes.

2015: Hemp food industry pioneers Manitoba Harvest and Hemp Oil Canada merge.

2016: Product innovations continue and hemp as an ingredient gains popularity, making hemp foods easier than ever to add into everyday eating.

Fun Fact!

Back in the 1700s, farmers in certain U.S. colonies were required by law to grow hemp as an essential crop.

Through the Years

1606: French Botanist Louis Hebert planted the first hemp crop in North America in Port Royal, Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia).

1770s: In Virginia (and some other colonies), farmers are required by law to grow hemp.

1776: The U.S. Declaration of Independence is drafted on hemp paper.

1797: The U.S.S. Constitution is outfitted with hemp sails and rigging.

1790s: U.S. founding fathers George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams grow hemp.

1800s: Upper Canada’s Lieutenant Governor, on behalf of the King of England, distributed free hemp seed to Canadian farmers.

1840s: Abraham Lincoln uses hemp oil to fuel his household lamps.

1890s: USDA Chief Botanist begins growing hemp varieties at the current site of the Pentagon and continues until the 1940s.

1916: USDA (Bulletin No. 404) shows that hemp produces four times more paper per acres than trees!

1928: The Canadian House of Commons encourages Canadian farmers to grow hemp.

1937: Hemp was strictly regulated by the Marijuana Tax Act, largely due to confusion with other kinds of cannabis. Hemp could only be grown through specially issued government tax stamps, making any type of possession/transfer without a tax stamp illegal.

1938: Popular Mechanics Magazine determines that over 25,000 different products could be made from hemp and declares hemp as the “New Billion Dollar Crop.”

1942: Henry Ford builds an experimental car with panels partially made from hemp fibre. That same year, without any changes to the Marijuana Tax Act, the United States Army used their Hemp for Victory campaign to urge farmers to grow hemp to support them in World War II. Between 1942 and 1945, the U.S. cultivated 400,000 acres of hemp for their war effort.

1957: Once World War II had ended, demand for hemp decreased and so did hemp production. The last commercial hemp fields were planted in 1957 in Wisconsin.

1970: The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act went into effect abolishing the taxation approach of the Marijuana Tax Act, effectively making all cultivation of cannabis illegal by setting a zero tolerance for THC.

1992: Manitoba Harvest Hemp Foods’ Co-Founder Martin begins importing and manufacturing handmade hemp items.

1993: Martin conducts research and establishes important relationships with farmers and government leaders.

1994: Martin organizes industrial hemp events and helps establish the University of Manitoba Hemp Awareness Committee (UMHAC).

1995: UMHAC becomes the Manitoba Hemp Alliance and lobbies the Government of Manitoba for assistance in advancing hemp agriculture. Harry Enns, Manitoba’s Agriculture Minister at the time, approves a funding grant and offers the services of a New Crops Agronomist. In less than nine months, the first hemp crops are harvested.

1996: Hemp trial results indicate that hemp can be grown with undetectable amounts (less than 0.003%) of THC.

1998: Industrial hemp is legalized in Canada! Hemp foods begin exporting to the U.S.

1999: North Dakota, Minnesota, and Hawaii legalize the growing of industrial hemp at state level, but federally, industrial hemp is still illegal to grow in the U.S.

2001: The United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) begins a campaign to make sales of all hemp foods illegal in the U.S. The Hemp Industries Association (HIA), Dr. Bronner’s, and other companies that offer hemp products take legal action against the DEA.

2004: Ninth Circuit Court rules in favour of the Hemp Industries Association and protects sales of hemp foods and body care products in the U.S.

2006: New innovations in hemp processing and new hemp products hit the market.

2010: Hemp Industries Association estimates $419 million in U.S. retail sales of hemp products.

2012: A record setting year in terms of the number of industrial hemp acres seeded in Canada. The number of acres is nine times the acres seeded in 1998 when industrial hemp was legalized.

2013: Annual U.S. retail sales of hemp products exceeds $581 million. Industrial hemp celebrates fifteen years of legalization in Canada.

2014: U.S. President Barack Obama signs Federal Farm Bill with hemp amendment, allowing states with hemp legislation in place to grow hemp for research purposes.

2015: Hemp food industry pioneers Manitoba Harvest and Hemp Oil Canada merge.

2016: Product innovations continue and hemp as an ingredient gains popularity, making hemp foods easier than ever to add into everyday eating.

Fun Fact!

Back in the 1700s, farmers in certain U.S. colonies were required by law to grow hemp as an essential crop.

Medical History Timeline

Terminology

Cannabis – the Latin term from Greek and older origin for a group of medicinal herbs of the family Cannabaceae used in traditional medicine. The group includes Cannabis {Indica, Sativa, Americana, Africans and Ruderalis} with a Sativa/Indica cross being in most commonly used.

Marihuana – marijuana; a slang term adopted for the Cannabis herb {See: William Randolph Hearst, Spanish American war, Poncha Villa, La Coocaracha}.

Marihuana – marijuana; a slang term adopted for the Cannabis herb {See: William Randolph Hearst, Spanish American war, Poncha Villa, La Coocaracha}.

Cannabinoid – one of the 60 {according to PDR} to 420 {asst. medical literature} medical constituents of the Cannabis herb.

Hemp – old world term for Cannabis usually associated with the non drug fibers used in rope and sail making and about 50,000 other industrial products.

THC – short for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, considered to be the most psychoactive Cannabinoid and the active ingredient in Cannabis.

CBD – short for Cannabidiol one of the least psychoactive and most anti-inflammatory Cannabinoids.

As you read this timeline, note that the treatment of disease with Cannabis [marijuana] has until very recently been done with tinctures and extracts. That is, most smoking of cannabis, for medicine in particular, is a function of prohibition. It takes much, much less of the plant material to gain a medicinal effect by smoking than by eating and cannabis is quite simply too expensive to make a tincture or extract when it’s price is increased by several thousand percent because of the war on drugs.

This point cannot be overemphasized because as you will read below, without the risk of smoking, cannabis poses a risk which is comparable with the safest medicines currently in use. {MK 1999}

Medical Cannabis History Timeline

Five thousand years ago, a Chinese emperor named Shen Nung prescribed cannabis for beriberi, malaria, rheumatism, constipation, absent-mindedness, and menstrual cramps.

In ancient India, cannabis was valued as a way to lower fevers and relieve dysentery. The drug was seen by some as a gift from the Gods. Reference: Marijuana: Current Facts, Figures and Information, Brent Q. Hafen and David Souler

In his influential book Materia Medica, published in 70 A.D., Roman physician Pedacius Dioscorides recommended cannabis to treat earache and diminished sexual desire.

1854

More recently, The 1854 United States Dispensary said this about cannabis;

Extract of hemp acts as a decided aphrodisiac, increases the appetite, and occasionally induces the cataleptic state. In morbid states it has been found to produce sleep, to allay spasm, to compose nervous inquietude, and to relieve pain. In these respects it resembles opium in its operation; but it differs from that narcotic in not diminishing the appetite, checking the secretions, or constipating the bowels. It is much less certain in its effects; but may sometimes be preferably employed, when opium is contraindicated by its nauseating or constipating effects. The complaints to which it has been specially recommended are neuralgia, gout, tetanus, hydrophobia, epidemic cholera, convulsions, chorea, hysteria, mental depression, insanity, and uterine hemorrhage. Dr. Alexander Christison, of Edinburgh, has found it to have the property of hastening and increasing the contractions of the uterus in delivery. It acts very quickly, and without anesthetic effect. It appears, however, to exert this influence only in a certain proportion of cases.

1938

”’Marijuana was made illegal in this century {1937/8} by congress over the objection of the American medical Association.

Dr. W. C Woodward of the American medical Association {AMA} was the only witness to oppose the bill. The legislative activities committee of the AMA wrote to protest the impending legislation {Grinspoon 1971}:

There is positively no evidence to indicate the abuse of cannabis as a medical agent or to show that its medicinal use is leading to the development of cannabis addiction. Cannabis at the present time is slightly used for medicinal purposes, but it would seem worthwhile to maintain its status as a medicinal agent… There is a possibility that a restudy of the drug by modern means may show other advantages to be derived from its medicinal use. [p. 226]

1941

Against all medical advice, the Marijuana Tax Act was approved by congress in 1937 and cannabis preparations were removed from the United States pharmacopoeia in 1941 {Bonnie and Whitebread 1974}. As Walton {1938, 162} noted, “Sasman in 1937 listed 28 pharmaceuticals which contained Cannabis indica. Most of the manufacturers are now removing cannabis from such combinations since the 1937 federal restrictions make it inconvenient to use such formulae”

1944

Only a few years later, the LaGuardia Committee took a clear-headed look at the marijuana “problem” in New York and found most of the claims that it caused crime, violence, insanity and death were completely unsubstantiated.

In regard to medical use, the LaGuardia report said;

“Marijuana has two qualities which suggest it may have useful actions in man.

The first is the typical euphoria-producing action which might be applicable in the treatment of various types of mental depression; the second is the rather unique property which results in stimulation of appetite” [1944, 147]

It is interesting that the committee did not shrink from commending euphoria itself as having therapeutic potential, and it noted more than 50 years ago the greatest contemporary {1990’s} use of cannabis as an appetite stimulant for patients with cancer, Aids or Hepatitis C.

1970

“The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 placed illicit drugs in one of five schedules, and the final decision about which schedule a drug was put in was made not by medical experts but by the Justice Department-the attorney general (John Mitchell) and the

Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, later named the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

Cannabis and it’s derivatives were placed in schedule I, for drugs with a high potential for abuse and no medical use (Baum 1996).

Ironicaly, two new medical uses were discovered shortly after the law was passed. the first was the ability of Cannabis to reduce interoccular pressure (Hepler and Frank 1971; Hepler, Frank and Petrus 1976; Roffman 1982; Colasanti 1986;

Adler and Geller 1986), which suggested its use as a treatment for glaucoma.

Robert Randall, a schoolteacher suffering from glaucoma who was arrested for using cannabis to keep from going blind, fought

his case through the courts and finally in 1976 forced the federal government to provide him with cannabis for this purpose–the first legal marijuana smoker in the United States since 1937.

The second discovery can be considered new because of a new context, the horrors of more than 40 kinds of chemotherapy used by contemporary doctors as treatment for cancer (Roffman 1982). The most frequent toxic side effect of chemotherapy is violent, uncontrollable nausea and vomiting that lasts for hours, and conventional antiemetics often do not help. Patients who smoked cannabis before chemotherapy, however, reported to their doctors that the illegal drug helped them enormously, stopping the vomiting and even making them hungry (Grinspoon and Bakalar 1995).

This led to many clinical reports on the antiemetic effect of cannabis and the cannabinoids, starting with Sallen, Zinberg, and Frei (1975). Most of the research in this field has been summarized by Regelson et al. (1976), Roffman (1982), Levitt (1986), and Randall (1990). The successful use of cannabis in cancer chemotherapy led to the marketing of an expensive synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol under the name Marinol and rescheduling of this synthetic drug into Schedule II, though the plant and THC extracted from the natural source, remain in Schedule I.

The proven antiemetic value of cannabis also led to its use by many AIDS patients in the mid 1980’s, both as an appetite stimulant against the AIDS wasting syndrome and as a remedy against the intense nausea often caused by the HIV’s gradual takeover of the immune system and by the toxicity of AZT therapy. There are AIDS and cancer patients all over the country using cannabis for these purposes, regardless of the laws. Ironically, so many people with AIDS applied for admission to the federal “Compassionate Access” program for marijuana that in 1992 the United States Department of Health and Human Services shut the program down.”

{Reference: Cannabis in Medical Practice, M.L.Mathre 1997}

Terminology

Cannabis – the Latin term from Greek and older origin for a group of medicinal herbs of the family Cannabaceae used in traditional medicine. The group includes Cannabis {Indica, Sativa, Americana, Africans and Ruderalis} with a Sativa/Indica cross being in most commonly used.

Marihuana – marijuana; a slang term adopted for the Cannabis herb {See: William Randolph Hearst, Spanish American war, Poncha Villa, La Coocaracha}.

Marihuana – marijuana; a slang term adopted for the Cannabis herb {See: William Randolph Hearst, Spanish American war, Poncha Villa, La Coocaracha}.Cannabinoid – one of the 60 {according to PDR} to 420 {asst. medical literature} medical constituents of the Cannabis herb.

Hemp – old world term for Cannabis usually associated with the non drug fibers used in rope and sail making and about 50,000 other industrial products.

THC – short for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, considered to be the most psychoactive Cannabinoid and the active ingredient in Cannabis.

CBD – short for Cannabidiol one of the least psychoactive and most anti-inflammatory Cannabinoids.

As you read this timeline, note that the treatment of disease with Cannabis [marijuana] has until very recently been done with tinctures and extracts. That is, most smoking of cannabis, for medicine in particular, is a function of prohibition. It takes much, much less of the plant material to gain a medicinal effect by smoking than by eating and cannabis is quite simply too expensive to make a tincture or extract when it’s price is increased by several thousand percent because of the war on drugs.

This point cannot be overemphasized because as you will read below, without the risk of smoking, cannabis poses a risk which is comparable with the safest medicines currently in use. {MK 1999}

Medical Cannabis History Timeline

Five thousand years ago, a Chinese emperor named Shen Nung prescribed cannabis for beriberi, malaria, rheumatism, constipation, absent-mindedness, and menstrual cramps.

In ancient India, cannabis was valued as a way to lower fevers and relieve dysentery. The drug was seen by some as a gift from the Gods. Reference: Marijuana: Current Facts, Figures and Information, Brent Q. Hafen and David Souler

In his influential book Materia Medica, published in 70 A.D., Roman physician Pedacius Dioscorides recommended cannabis to treat earache and diminished sexual desire.

1854

More recently, The 1854 United States Dispensary said this about cannabis;

Extract of hemp acts as a decided aphrodisiac, increases the appetite, and occasionally induces the cataleptic state. In morbid states it has been found to produce sleep, to allay spasm, to compose nervous inquietude, and to relieve pain. In these respects it resembles opium in its operation; but it differs from that narcotic in not diminishing the appetite, checking the secretions, or constipating the bowels. It is much less certain in its effects; but may sometimes be preferably employed, when opium is contraindicated by its nauseating or constipating effects. The complaints to which it has been specially recommended are neuralgia, gout, tetanus, hydrophobia, epidemic cholera, convulsions, chorea, hysteria, mental depression, insanity, and uterine hemorrhage. Dr. Alexander Christison, of Edinburgh, has found it to have the property of hastening and increasing the contractions of the uterus in delivery. It acts very quickly, and without anesthetic effect. It appears, however, to exert this influence only in a certain proportion of cases.

1938

”’Marijuana was made illegal in this century {1937/8} by congress over the objection of the American medical Association.

Dr. W. C Woodward of the American medical Association {AMA} was the only witness to oppose the bill. The legislative activities committee of the AMA wrote to protest the impending legislation {Grinspoon 1971}:

There is positively no evidence to indicate the abuse of cannabis as a medical agent or to show that its medicinal use is leading to the development of cannabis addiction. Cannabis at the present time is slightly used for medicinal purposes, but it would seem worthwhile to maintain its status as a medicinal agent… There is a possibility that a restudy of the drug by modern means may show other advantages to be derived from its medicinal use. [p. 226]

1941

Against all medical advice, the Marijuana Tax Act was approved by congress in 1937 and cannabis preparations were removed from the United States pharmacopoeia in 1941 {Bonnie and Whitebread 1974}. As Walton {1938, 162} noted, “Sasman in 1937 listed 28 pharmaceuticals which contained Cannabis indica. Most of the manufacturers are now removing cannabis from such combinations since the 1937 federal restrictions make it inconvenient to use such formulae”

1944

Only a few years later, the LaGuardia Committee took a clear-headed look at the marijuana “problem” in New York and found most of the claims that it caused crime, violence, insanity and death were completely unsubstantiated.

In regard to medical use, the LaGuardia report said;

“Marijuana has two qualities which suggest it may have useful actions in man.

The first is the typical euphoria-producing action which might be applicable in the treatment of various types of mental depression; the second is the rather unique property which results in stimulation of appetite” [1944, 147]

It is interesting that the committee did not shrink from commending euphoria itself as having therapeutic potential, and it noted more than 50 years ago the greatest contemporary {1990’s} use of cannabis as an appetite stimulant for patients with cancer, Aids or Hepatitis C.

1970

“The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 placed illicit drugs in one of five schedules, and the final decision about which schedule a drug was put in was made not by medical experts but by the Justice Department-the attorney general (John Mitchell) and the

Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, later named the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

Cannabis and it’s derivatives were placed in schedule I, for drugs with a high potential for abuse and no medical use (Baum 1996).

Ironicaly, two new medical uses were discovered shortly after the law was passed. the first was the ability of Cannabis to reduce interoccular pressure (Hepler and Frank 1971; Hepler, Frank and Petrus 1976; Roffman 1982; Colasanti 1986;

Adler and Geller 1986), which suggested its use as a treatment for glaucoma.

Robert Randall, a schoolteacher suffering from glaucoma who was arrested for using cannabis to keep from going blind, fought

his case through the courts and finally in 1976 forced the federal government to provide him with cannabis for this purpose–the first legal marijuana smoker in the United States since 1937.

The second discovery can be considered new because of a new context, the horrors of more than 40 kinds of chemotherapy used by contemporary doctors as treatment for cancer (Roffman 1982). The most frequent toxic side effect of chemotherapy is violent, uncontrollable nausea and vomiting that lasts for hours, and conventional antiemetics often do not help. Patients who smoked cannabis before chemotherapy, however, reported to their doctors that the illegal drug helped them enormously, stopping the vomiting and even making them hungry (Grinspoon and Bakalar 1995).

This led to many clinical reports on the antiemetic effect of cannabis and the cannabinoids, starting with Sallen, Zinberg, and Frei (1975). Most of the research in this field has been summarized by Regelson et al. (1976), Roffman (1982), Levitt (1986), and Randall (1990). The successful use of cannabis in cancer chemotherapy led to the marketing of an expensive synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol under the name Marinol and rescheduling of this synthetic drug into Schedule II, though the plant and THC extracted from the natural source, remain in Schedule I.

The proven antiemetic value of cannabis also led to its use by many AIDS patients in the mid 1980’s, both as an appetite stimulant against the AIDS wasting syndrome and as a remedy against the intense nausea often caused by the HIV’s gradual takeover of the immune system and by the toxicity of AZT therapy. There are AIDS and cancer patients all over the country using cannabis for these purposes, regardless of the laws. Ironically, so many people with AIDS applied for admission to the federal “Compassionate Access” program for marijuana that in 1992 the United States Department of Health and Human Services shut the program down.”

{Reference: Cannabis in Medical Practice, M.L.Mathre 1997}

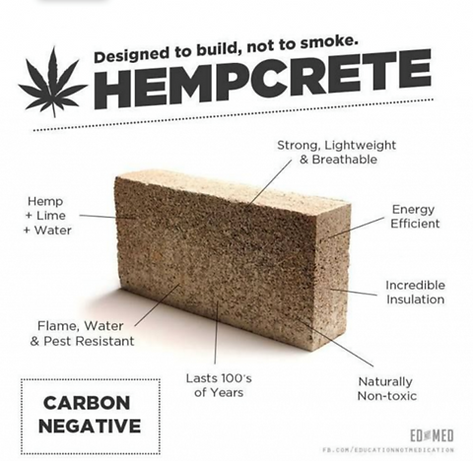

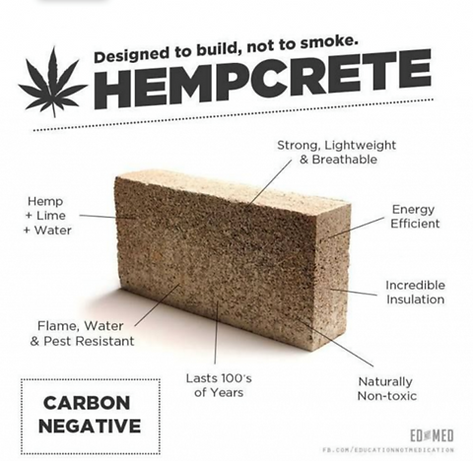

The Differences Between Hemp and Cannabis

While hemp and cannabis are both derived from the same species (Cannabis sativa), there are major differences in the characteristics of the respective plant strains that produce industrial hemp on the one hand, and cannabis products on the other. Most people understand these differences in terms like “cannabis is a drug but hemp isn’t”, and “hemp comes from the male plant and cannabis comes from the female plant.” However, the reality of the situation is a little more complex.

WHAT IS HEMP?

In Short: hemp is a strain of the Cannabis sativa plant that is grown primarily for use in industrial applications. It has been specifically cultivated to produce a low tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content and a high cannabidiol (CBD) content.

THC is the psychoactive constituent of cannabis, and is responsible for producing the effects of the drug. CBD is another active ingredient present in Cannabis sativa plants, and it largely acts to neutralize the psychoactive effects of THC.

Since hemp strains have very little THC and a lot of CBD, they do not produce psychoactive effects when ingested. Rather, hemp is used for a wide range of industrial purposes, including:

Hemp also has important applications in plant-based pest control, and it has been used for many years as a natural method of controlling the growth of weeds and invasive plants. Because they have such dense growth characteristics, hemp plants effectively “crowd out” weeds that are present in the soil, killing them off without the need for pesticides.

More recently, hemp has also been considered as a potential source of biofuel, and hemp plants can also be specially treated to produce ethanol, or alcohol fuel. Currently, most biofuel is produced from other sources, such as cereal grains and dead plant matter. However, research into the viability of hemp as an alternative fuel source is ongoing.

HEMP VS. WEED: HOW HEMP DIFFERS FROM CANNABIS

Cannabis sativa strains that produce cannabis contain many times more THC than the strains the produce hemp.

In Canada, a Cannabis sativa plant can only be classified as hemp if it contains 0.3 percent THC or less. Anything exceeding that threshold is technically considered cannabis, though most Cannabis sativa plants that are cultivated for their cannabis actually contain between about 5 percent and 30 percent THC.

While it is true that most hemp plants are male and do not produce flowering cannabis buds, their lack of psychoactive effects is mainly the result of many years of selective breeding. Hemp plants are also hardier, grow more quickly, and tend to be taller. Cannabis plants, on the other hand, require much more carefully controlled growing conditions to produce optimal results.

Many of the differences in these respective forms of Cannabis sativa stem from decades of cannabis prohibition. While hemp plants are very versatile with a broad range of industrial uses, governments wanted to ensure they were incapable of producing intoxicating effects. This drove the production of cannabis plants almost exclusively underground for a long period of time, a situation that is only now beginning to change.

While hemp and cannabis are both derived from the same species (Cannabis sativa), there are major differences in the characteristics of the respective plant strains that produce industrial hemp on the one hand, and cannabis products on the other. Most people understand these differences in terms like “cannabis is a drug but hemp isn’t”, and “hemp comes from the male plant and cannabis comes from the female plant.” However, the reality of the situation is a little more complex.

WHAT IS HEMP?

In Short: hemp is a strain of the Cannabis sativa plant that is grown primarily for use in industrial applications. It has been specifically cultivated to produce a low tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content and a high cannabidiol (CBD) content.

THC is the psychoactive constituent of cannabis, and is responsible for producing the effects of the drug. CBD is another active ingredient present in Cannabis sativa plants, and it largely acts to neutralize the psychoactive effects of THC.

Since hemp strains have very little THC and a lot of CBD, they do not produce psychoactive effects when ingested. Rather, hemp is used for a wide range of industrial purposes, including:

- Clothing and textiles

- Building materials

- Plastic and composite materials

- Paper

- Cordage

- Cosmetics

- Food

Hemp also has important applications in plant-based pest control, and it has been used for many years as a natural method of controlling the growth of weeds and invasive plants. Because they have such dense growth characteristics, hemp plants effectively “crowd out” weeds that are present in the soil, killing them off without the need for pesticides.

More recently, hemp has also been considered as a potential source of biofuel, and hemp plants can also be specially treated to produce ethanol, or alcohol fuel. Currently, most biofuel is produced from other sources, such as cereal grains and dead plant matter. However, research into the viability of hemp as an alternative fuel source is ongoing.

HEMP VS. WEED: HOW HEMP DIFFERS FROM CANNABIS

Cannabis sativa strains that produce cannabis contain many times more THC than the strains the produce hemp.

In Canada, a Cannabis sativa plant can only be classified as hemp if it contains 0.3 percent THC or less. Anything exceeding that threshold is technically considered cannabis, though most Cannabis sativa plants that are cultivated for their cannabis actually contain between about 5 percent and 30 percent THC.

While it is true that most hemp plants are male and do not produce flowering cannabis buds, their lack of psychoactive effects is mainly the result of many years of selective breeding. Hemp plants are also hardier, grow more quickly, and tend to be taller. Cannabis plants, on the other hand, require much more carefully controlled growing conditions to produce optimal results.

Many of the differences in these respective forms of Cannabis sativa stem from decades of cannabis prohibition. While hemp plants are very versatile with a broad range of industrial uses, governments wanted to ensure they were incapable of producing intoxicating effects. This drove the production of cannabis plants almost exclusively underground for a long period of time, a situation that is only now beginning to change.

Were we all eating a lot more CBD before prohibition?

Posted on June 27 2016

I came across an interesting theory recently regarding why CBD and other cannabinoids seem to solve so many modern health problems. The theory goes something like this - that when farm animals were fed industrial hemp containing CBD before the prohibition of marijuana and the discontinued use of hemp as animal fodder, people were consuming much more CBD that came in through the food chain. This in turn led to the health benefits of CBD and other cannabinoids, solving problems traditionally medicated with CBD treatment. These problems cover everything from digestive tract issues to arthritis.

On the surface, this theory does indeed seem to have some credibility. CBD could well be transferred in the meat and fats of animals we eat. However, one would also have to have evidence that people were actually healthier in regards to illnesses that can be treated by CBD before prohibition. This doesn’t seem to have much evidence to back it up. When looking, I couldn’t find any studies confirming that people who ate hemp fed (i.e. animals that ate hemp as part of their diet) food products seemed to have less illnesses on the whole.

There could be a great many reasons for this. The main significant reason one would suspect is the lack of scientific studies done on large groups of people prior to prohibition of hemp in the 1930s. Another is the fact that many of the illnesses we would treat with CBD have gone under many different names over the years, and some are pretty ambiguous to say the least.

Maybe CBD is the reason that we seem to have developed health problems that we weren’t aware of before. Many more people than ever before are finding themselves with symptoms of Irritable bowel syndrome, gluten intolerance and other ‘twenty-first century’ diseases. Until we have the ability to study CBD and its effects on the food chain from hemp fed animals, we really won’t be able to tell whether we had more CBD in our diet before the prohibition of marijuana, but it’s definitely possible.

Posted on June 27 2016

I came across an interesting theory recently regarding why CBD and other cannabinoids seem to solve so many modern health problems. The theory goes something like this - that when farm animals were fed industrial hemp containing CBD before the prohibition of marijuana and the discontinued use of hemp as animal fodder, people were consuming much more CBD that came in through the food chain. This in turn led to the health benefits of CBD and other cannabinoids, solving problems traditionally medicated with CBD treatment. These problems cover everything from digestive tract issues to arthritis.

On the surface, this theory does indeed seem to have some credibility. CBD could well be transferred in the meat and fats of animals we eat. However, one would also have to have evidence that people were actually healthier in regards to illnesses that can be treated by CBD before prohibition. This doesn’t seem to have much evidence to back it up. When looking, I couldn’t find any studies confirming that people who ate hemp fed (i.e. animals that ate hemp as part of their diet) food products seemed to have less illnesses on the whole.

There could be a great many reasons for this. The main significant reason one would suspect is the lack of scientific studies done on large groups of people prior to prohibition of hemp in the 1930s. Another is the fact that many of the illnesses we would treat with CBD have gone under many different names over the years, and some are pretty ambiguous to say the least.

Maybe CBD is the reason that we seem to have developed health problems that we weren’t aware of before. Many more people than ever before are finding themselves with symptoms of Irritable bowel syndrome, gluten intolerance and other ‘twenty-first century’ diseases. Until we have the ability to study CBD and its effects on the food chain from hemp fed animals, we really won’t be able to tell whether we had more CBD in our diet before the prohibition of marijuana, but it’s definitely possible.

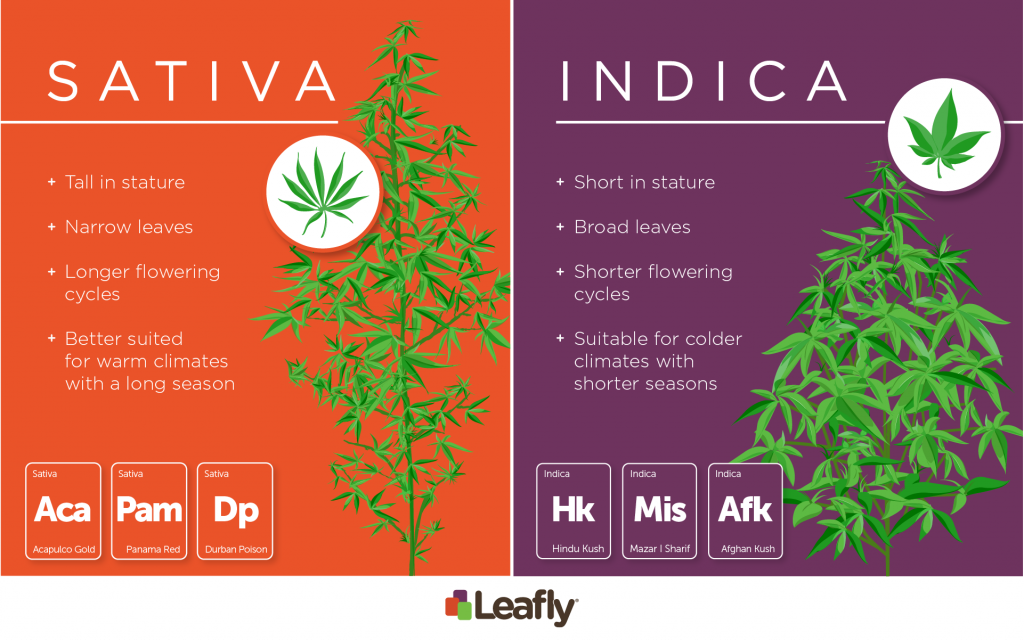

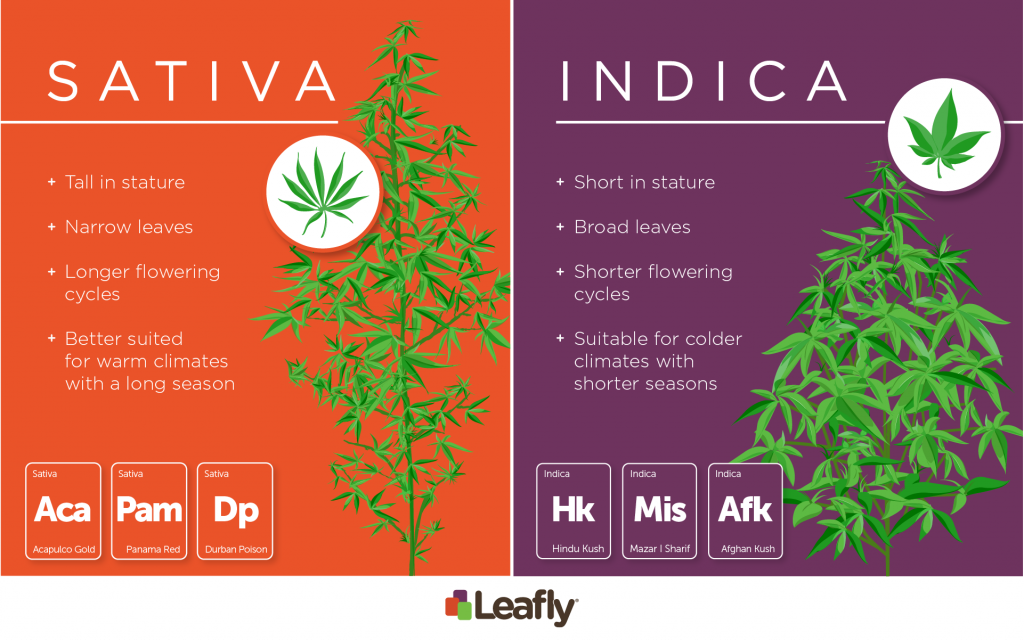

YOUR GUIDE TO INDICA, SATIVA, AND HYBRID CANNABIS

Part 1, Sativa vs. Indica: An Overview of Cannabis Types

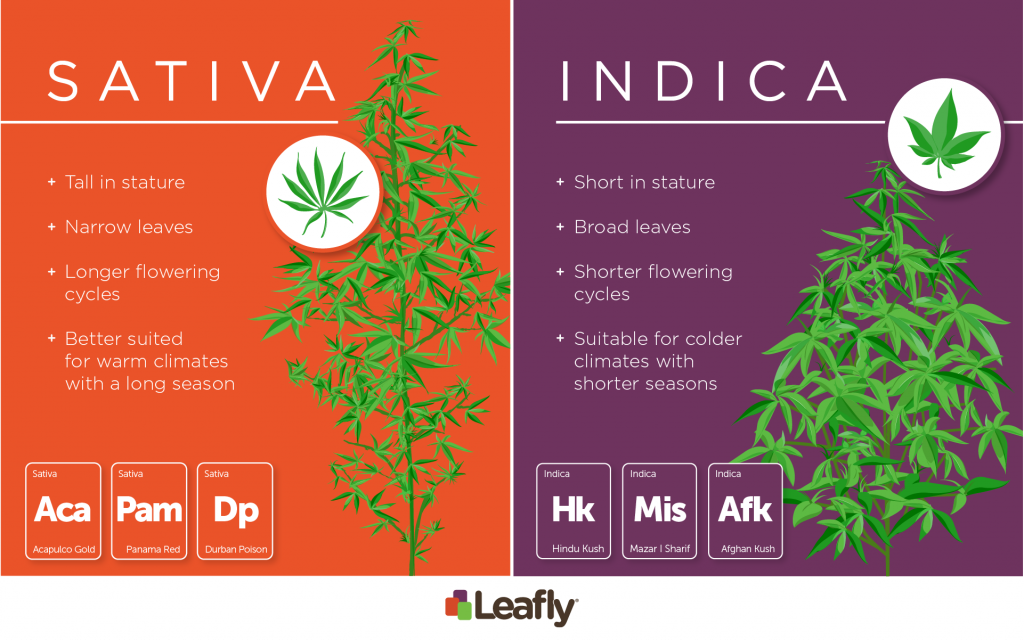

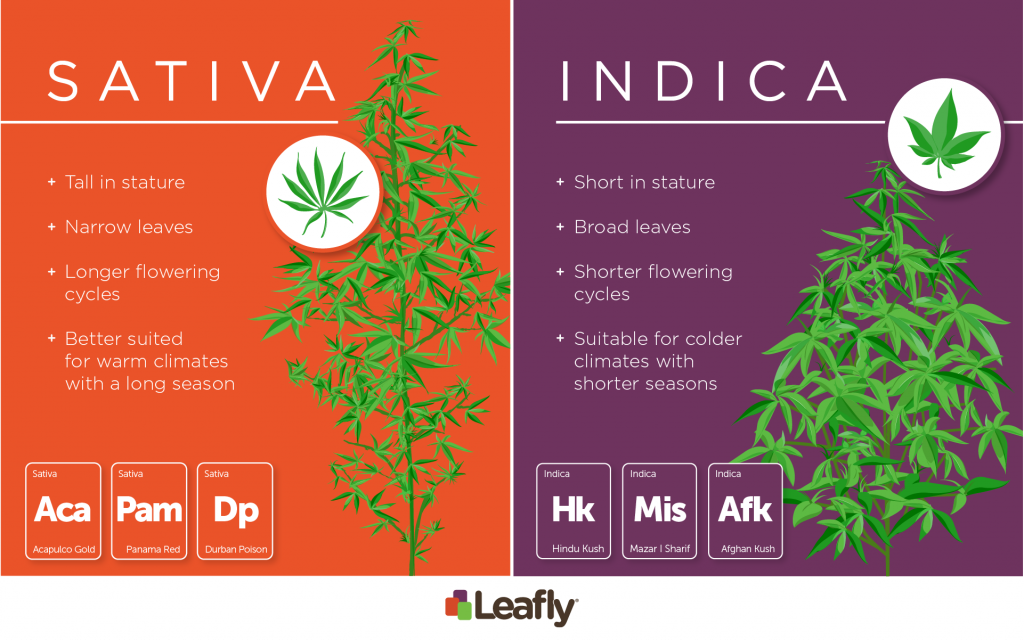

When browsing cannabis strains or purchasing cannabis at a shop, you may notice strains are commonly broken up into two distinct groups: indica and sativa. Most consumers have used these two cannabis types as a touchstone for predicting effects:

RELATED STORY

The Leafly Starter Pack: A Comprehensive Guide to Recreational Cannabis

However, data collected by cannabis researchers suggests these categories aren’t as prescriptive as one might hope—in other words, there’s little evidence to suggest that indicas and sativas exhibit a consistent pattern of chemical profiles that would make one inherently sedating and the other uplifting. We do know that indica and sativa cannabis strains look different and grow differently, but this distinction is primarily useful only to cannabis cultivators.

So how exactly did the words “indica” and “sativa” make it into the vernacular of cannabis consumers worldwide, and to what extent are they meaningful when choosing a strain?

Indica and Sativa: Origin and Evolution of the Terms

(Amy Phung/Leafly)

The words “indica” and “sativa” were introduced in the 18th century to describe different species of cannabis: Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica.The term sativa, named by Carl Linneaus, described hemp plants found in Europe and western Eurasia, where it was cultivated for its fiber and seeds. Cannabis indica, named by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, describes the psychoactive varieties discovered in India, where it was harvested for its seeds, fiber, and hashish production.

RELATED STORY

The Cannabis Taxonomy Debate: Where Do Indica and Sativa Classifications Come From?

Although the cannabis varieties we consume largely stem from Cannabis indica, both terms are used–even if erroneously–to organize the thousands of strains circulating the market today.

Here’s how terms have shifted since their earliest botanical definitions:

Indica vs. Sativa Effects: What Does the Research Say?

This three-type system we use to predict cannabis effects is no doubt convenient, especially when first entering the vast, overwhelming world of cannabis. With so many strains and products to choose from, where else are we to begin?

“The clinical effects of the cannabis chemovar have nothing to do with whether the plant is tall and sparse vs. short and bushy, or whether the leaflets are narrow or broad.”

Ethan Russo, neurologist and cannabis researcher

The answer is cannabinoids and terpenes, two words you should put in your back pocket if you haven’t already. We’ll get to know these terms shortly.

But first, we asked two prominent cannabis researchers if sativa/indica classification should have any bearing on a consumer’s strain selection. Ethan Russo is a neurologist whose research in cannabis psychopharmacology is respected worldwide, and Jeffrey Raber, Ph.D., is a chemist who founded the first independent testing lab to analyze cannabis terpenes in a commercial capacity, The Werc Shop.

“The way that the sativa and indica labels are utilized in commerce is nonsense,” Russo told Leafly. “The clinical effects of the cannabis chemovar have nothing to do with whether the plant is tall and sparse vs. short and bushy, or whether the leaflets are narrow or broad.”

RELATED STORY

Cannabis Anatomy: The Parts of the Plant

Raber agreed, and when asked if budtenders should be guiding consumers with terms like “indica” and “sativa,” he replied, “There is no factual or scientific basis to making these broad sweeping recommendations, and it needs to stop today. What we need to seek to understand better is which standardized cannabis composition is causing which effects, when delivered in which fashions, at which specific dosages, to which types of [consumers].”

What this means is not all sativas will energize you, and not all indicas will sedate you. You may notice a tendency for these so-called sativas to be uplifting or for these indicas to be relaxing, especially when we expect to feel one way or the other. Just note that there’s no hard-and-fast rule and no determinant chemical data that supports a perfect predictive pattern.

If Indica vs. Sativa Isn’t Predictive of Effects, What Is?

The effects of any given cannabis strain depend on a number of different factors, including the product’s chemical profile, your unique biology and tolerance, dose, and consumption method. Understand how these factors change the experience and you’ll have the best chance of finding that perfect strain for you.

Cannabinoids

The cannabis plant is comprised of hundreds of chemical compounds that create a unique harmony of effects, which is primarily led by cannabinoids and terpenes. Cannabinoids like THC and CBD (the two most common) are the main drivers of cannabis’ therapeutic and recreational effects:

RELATED STORY

Predicting Cannabis Strain Effects From THC and CBD Levels

Terpenes

If you’ve ever used aromatherapy to relax or invigorate your mind and body, you understand the basics of terpenes. Terpenes are aromatic compounds commonly produced by plants and fruit. They can be found in lavender flowers, oranges, hops, pepper, and of course, cannabis. Secreted by the same glands that ooze THC and CBD, terpenes are what make cannabis smell like berries, citrus, pine, fuel, etc.

“Terpenes seem to be major players in driving the sedating or energizing effects.”

Jeffrey Raber, Founder of The Werc Shop

Like essential oils vaporized in a diffuser, cannabis terpenes can make us feel stimulated or sedated, depending on which ones are produced. Pinene, for example, is an alerting terpene while linalool has relaxing properties. There are many types of terpenes in cannabis, and it’s worth familiarizing yourself with at least the most common.

“Terpenes seem to be major players in driving the sedating or energizing effects,” Raber said. “Which terpenes cause which effects is apparently much more complicated than all of us would like, as it seems to [vary based on specific] ones and their relative ratios to each other and the cannabinoids.”

According to Raber, a strain’s indica or sativa morphology does not specifically determine these aromas and effects. However, you may find consistency among individual strains. The strain Tangie, for example, delivers a distinctive citrus aroma, while DJ Short’s Blueberry should never fail to offer the hallmark scent of ripe berry.

If you can, smell the strains you’re considering for purchase. Find the aromas that stand out to you and give them a try. In time, your intuition and knowledge of cannabinoids and terpenes will guide you to your favorite strains and products.

RELATED STORY

At the Trichome Institute, Students Learn to Predict Cannabis Effects by Aroma

Biology, Dosing, and Consumption Method

Lastly, consider the following questions when choosing the right strain or product for you.

RELATED STORY

The Different Ways to Smoke and Consume Cannabis

What Cannabis Strain Is Right for You?

Before choosing indica or sativa, it is important to consider a third cannabis type: hybrid. Hybrids are thought to fall somewhere in between the indica-sativa spectrum, depending on the traits they inherit from their parent strains.

This may seem overwhelming, especially if you’re a budtender whose job it is to guide consumers to the right product. Ironically, the more you know about cannabis, the more questions seem to arise. But understanding the basic properties of cannabinoids, terpenes, and consumption methods will often answer the most fundamental question of cannabis: What product is right for me?

Here are some helpful beginner resources to get you started:

“In the future, I’d like to see the terms ‘sativa’ and ‘indica’ be abandoned in favor of a system in which the consumer tells the budtender what s/he would like to have in terms of effects from their cannabis selection, and then study the offerings together,” Russo said. “If a buzz is all that is wanted, then high THC with limonene or terpinolene would be desirable. If someone, in contrast, has to work or study and treat their pain, then high CBD with low THC plus some alpha-pinene to reduce short-term memory impairment would be the ticket.”

Cannabis may not be as simple as we’d like, but its diversity and complexity is what makes it such a remarkable plant and tool for consumers of all types.

Lead image by Amy Phung/Leafly

Part 1, Sativa vs. Indica: An Overview of Cannabis Types

When browsing cannabis strains or purchasing cannabis at a shop, you may notice strains are commonly broken up into two distinct groups: indica and sativa. Most consumers have used these two cannabis types as a touchstone for predicting effects:

- Indica strains are believed to be physically sedating, perfect for relaxing with a movie or as a nightcap before bed.

- Sativa strains tend to provide more invigorating, uplifting cerebral effects that pair well with physical activity, social gatherings, and creative projects.

RELATED STORY

The Leafly Starter Pack: A Comprehensive Guide to Recreational Cannabis

However, data collected by cannabis researchers suggests these categories aren’t as prescriptive as one might hope—in other words, there’s little evidence to suggest that indicas and sativas exhibit a consistent pattern of chemical profiles that would make one inherently sedating and the other uplifting. We do know that indica and sativa cannabis strains look different and grow differently, but this distinction is primarily useful only to cannabis cultivators.

So how exactly did the words “indica” and “sativa” make it into the vernacular of cannabis consumers worldwide, and to what extent are they meaningful when choosing a strain?

Indica and Sativa: Origin and Evolution of the Terms

(Amy Phung/Leafly)

The words “indica” and “sativa” were introduced in the 18th century to describe different species of cannabis: Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica.The term sativa, named by Carl Linneaus, described hemp plants found in Europe and western Eurasia, where it was cultivated for its fiber and seeds. Cannabis indica, named by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, describes the psychoactive varieties discovered in India, where it was harvested for its seeds, fiber, and hashish production.

RELATED STORY

The Cannabis Taxonomy Debate: Where Do Indica and Sativa Classifications Come From?

Although the cannabis varieties we consume largely stem from Cannabis indica, both terms are used–even if erroneously–to organize the thousands of strains circulating the market today.

Here’s how terms have shifted since their earliest botanical definitions:

- Today, “sativa” refers to tall, narrow-leaf varieties of cannabis, thought to induce energizing effects. However, these narrow-leaf drug (NLD) varieties were originally Cannabis indica ssp. indica.

- “Indica” has come to describe stout, broad-leaf plants, thought to deliver sedating effects. These broad-leaf drug (BLD) varieties are technically Cannabis indica ssp. afghanica.

- What we call “hemp” refers to the industrial, non-intoxicating varieties harvested primarily for fiber, seeds, and CBD. However, this was originally named Cannabis sativa.

Indica vs. Sativa Effects: What Does the Research Say?

This three-type system we use to predict cannabis effects is no doubt convenient, especially when first entering the vast, overwhelming world of cannabis. With so many strains and products to choose from, where else are we to begin?

“The clinical effects of the cannabis chemovar have nothing to do with whether the plant is tall and sparse vs. short and bushy, or whether the leaflets are narrow or broad.”

Ethan Russo, neurologist and cannabis researcher

The answer is cannabinoids and terpenes, two words you should put in your back pocket if you haven’t already. We’ll get to know these terms shortly.

But first, we asked two prominent cannabis researchers if sativa/indica classification should have any bearing on a consumer’s strain selection. Ethan Russo is a neurologist whose research in cannabis psychopharmacology is respected worldwide, and Jeffrey Raber, Ph.D., is a chemist who founded the first independent testing lab to analyze cannabis terpenes in a commercial capacity, The Werc Shop.

“The way that the sativa and indica labels are utilized in commerce is nonsense,” Russo told Leafly. “The clinical effects of the cannabis chemovar have nothing to do with whether the plant is tall and sparse vs. short and bushy, or whether the leaflets are narrow or broad.”

RELATED STORY

Cannabis Anatomy: The Parts of the Plant

Raber agreed, and when asked if budtenders should be guiding consumers with terms like “indica” and “sativa,” he replied, “There is no factual or scientific basis to making these broad sweeping recommendations, and it needs to stop today. What we need to seek to understand better is which standardized cannabis composition is causing which effects, when delivered in which fashions, at which specific dosages, to which types of [consumers].”

What this means is not all sativas will energize you, and not all indicas will sedate you. You may notice a tendency for these so-called sativas to be uplifting or for these indicas to be relaxing, especially when we expect to feel one way or the other. Just note that there’s no hard-and-fast rule and no determinant chemical data that supports a perfect predictive pattern.

If Indica vs. Sativa Isn’t Predictive of Effects, What Is?

The effects of any given cannabis strain depend on a number of different factors, including the product’s chemical profile, your unique biology and tolerance, dose, and consumption method. Understand how these factors change the experience and you’ll have the best chance of finding that perfect strain for you.

Cannabinoids

The cannabis plant is comprised of hundreds of chemical compounds that create a unique harmony of effects, which is primarily led by cannabinoids and terpenes. Cannabinoids like THC and CBD (the two most common) are the main drivers of cannabis’ therapeutic and recreational effects:

- THC (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol) makes us feel hungry and high, and relieves symptoms like pain and nausea.

- CBD (cannabidiol) is a non-intoxicating compound known to alleviate anxiety, pain, inflammation, and many other medical ailments.

- THC-dominant strains are primarily chosen by consumers seeking a potent euphoric experience. These strains are also selected by patients treating pain, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and more. If you tend to feel anxious with THC-dominant strains or dislike other side effects associated with THC, try a strain with higher levels of CBD.

- CBD-dominant strains contain only small amounts of THC, and are widely used by those highly sensitive to THC or patients needing clear-headed symptom relief.

- Balanced THC/CBD strains contain balanced levels of THC, offering mild euphoria alongside symptom relief. These tend to be a good choice for novice consumers seeking an introduction to cannabis’ signature high.

RELATED STORY

Predicting Cannabis Strain Effects From THC and CBD Levels

Terpenes

If you’ve ever used aromatherapy to relax or invigorate your mind and body, you understand the basics of terpenes. Terpenes are aromatic compounds commonly produced by plants and fruit. They can be found in lavender flowers, oranges, hops, pepper, and of course, cannabis. Secreted by the same glands that ooze THC and CBD, terpenes are what make cannabis smell like berries, citrus, pine, fuel, etc.

“Terpenes seem to be major players in driving the sedating or energizing effects.”

Jeffrey Raber, Founder of The Werc Shop

Like essential oils vaporized in a diffuser, cannabis terpenes can make us feel stimulated or sedated, depending on which ones are produced. Pinene, for example, is an alerting terpene while linalool has relaxing properties. There are many types of terpenes in cannabis, and it’s worth familiarizing yourself with at least the most common.

“Terpenes seem to be major players in driving the sedating or energizing effects,” Raber said. “Which terpenes cause which effects is apparently much more complicated than all of us would like, as it seems to [vary based on specific] ones and their relative ratios to each other and the cannabinoids.”

According to Raber, a strain’s indica or sativa morphology does not specifically determine these aromas and effects. However, you may find consistency among individual strains. The strain Tangie, for example, delivers a distinctive citrus aroma, while DJ Short’s Blueberry should never fail to offer the hallmark scent of ripe berry.

If you can, smell the strains you’re considering for purchase. Find the aromas that stand out to you and give them a try. In time, your intuition and knowledge of cannabinoids and terpenes will guide you to your favorite strains and products.

RELATED STORY

At the Trichome Institute, Students Learn to Predict Cannabis Effects by Aroma

Biology, Dosing, and Consumption Method

Lastly, consider the following questions when choosing the right strain or product for you.

- How much experience do you have with cannabis? If your tolerance is low, consider a low-THC strain in low doses.

- Are you susceptible to anxiety or other side effects of THC? If so, try a strain high in CBD.

- Do you want the effects to last a long time? If you do, consider edibles (starting with a low dose). Conversely, if you seek a short-term experience, use inhalation methods or a tincture.

RELATED STORY

The Different Ways to Smoke and Consume Cannabis

What Cannabis Strain Is Right for You?

Before choosing indica or sativa, it is important to consider a third cannabis type: hybrid. Hybrids are thought to fall somewhere in between the indica-sativa spectrum, depending on the traits they inherit from their parent strains.

This may seem overwhelming, especially if you’re a budtender whose job it is to guide consumers to the right product. Ironically, the more you know about cannabis, the more questions seem to arise. But understanding the basic properties of cannabinoids, terpenes, and consumption methods will often answer the most fundamental question of cannabis: What product is right for me?

Here are some helpful beginner resources to get you started:

- Cannabis Strain Recommendations for Beginners and Low-Tolerance Consumers

- Cannabis Product Recommendations for First-Time Consumers

- The Best Cannabis Strains and Products for Every Situation

- How to Find the Best Experience and High for You

“In the future, I’d like to see the terms ‘sativa’ and ‘indica’ be abandoned in favor of a system in which the consumer tells the budtender what s/he would like to have in terms of effects from their cannabis selection, and then study the offerings together,” Russo said. “If a buzz is all that is wanted, then high THC with limonene or terpinolene would be desirable. If someone, in contrast, has to work or study and treat their pain, then high CBD with low THC plus some alpha-pinene to reduce short-term memory impairment would be the ticket.”

Cannabis may not be as simple as we’d like, but its diversity and complexity is what makes it such a remarkable plant and tool for consumers of all types.

Lead image by Amy Phung/Leafly

YOUR GUIDE TO INDICA, SATIVA, AND HYBRID CANNABIS

Part 2, Indica vs. Sativa Strains: Which Has More THC & CBD?

Raise your hand if you’ve heard someone say, “Indica strains produce more CBD and sativas have more THC.” Or maybe you’ve heard that claim in reverse. But which is true?

According to cannabis lab testing data, neither is. At least not in any significant way that could explain the perceived difference between these two cannabis types.

In other words, that indica isn’t sleepy because it has more CBD, and that sativa isn’t more energizing because it produced more THC.

But before we get too deep into the numbers, it’s important to first flip a popular notion on its head.

RELATED STORY

CBD vs. THC: What’s the Difference?

Indica & Sativa Designation Isn’t a Reliable Predictor of Effects

It’s possible you’ve noticed that indica and sativa strains look a bit different. One forms chunky, dense buds while the other often grows into airy, fluffy spears. The physical differences between indica and sativa plants allowed each to thrive in different climates, from rugged and cold highlands to tropical regions along the equator.

Click to enlarge. (Amy Phung/Leafly)

Cool, but what does that have to do with how indicas and sativas affect you? Nothing. Exactly.

Ethan Russo, prominent cannabis researcher and neurologist, put it this way:

“The way that the sativa and indica labels are utilized in commerce is nonsense. The clinical effects of the cannabis chemovar have nothing to do with whether the plant is tall and sparse vs. short and bushy, or whether the leaflets are narrow or broad.”

One way we know that this perceived correlation between plant type and effect is flawed is by looking at the chemical profiles—the compounds cannabis produces that contribute to the mood or experience of that strain.

Here, we’ll take a look at the average cannabinoid content of each strain type. Terpenes also play an important role in a strain’s effect, but don’t worry—we’ll get to that in the next installment.

RELATED STORY

Predicting Cannabis Strain Effects From THC and CBD Levels

CBD vs. THC in Indicas and Sativas

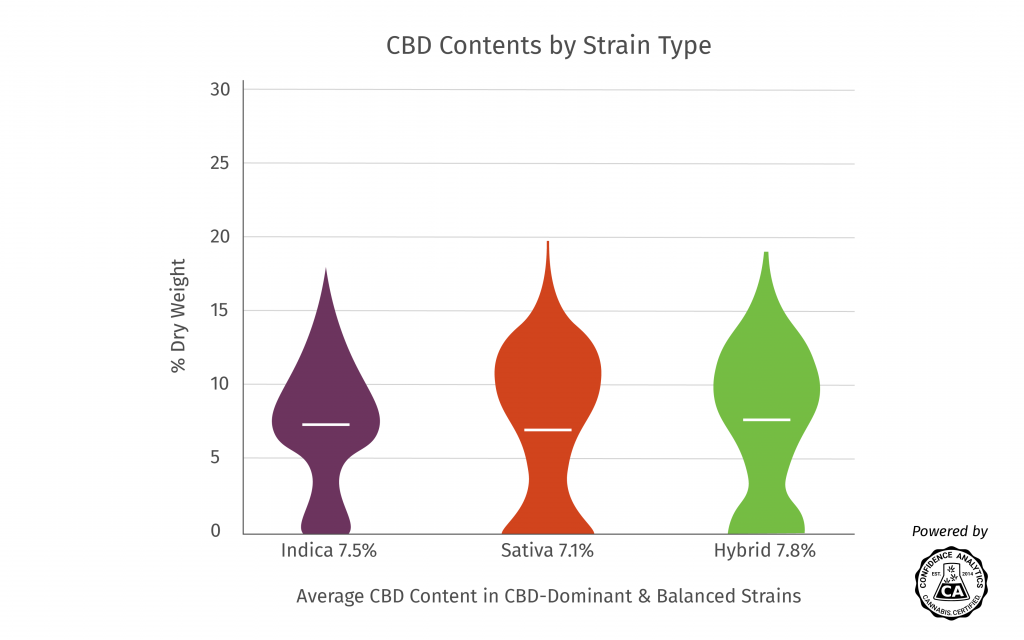

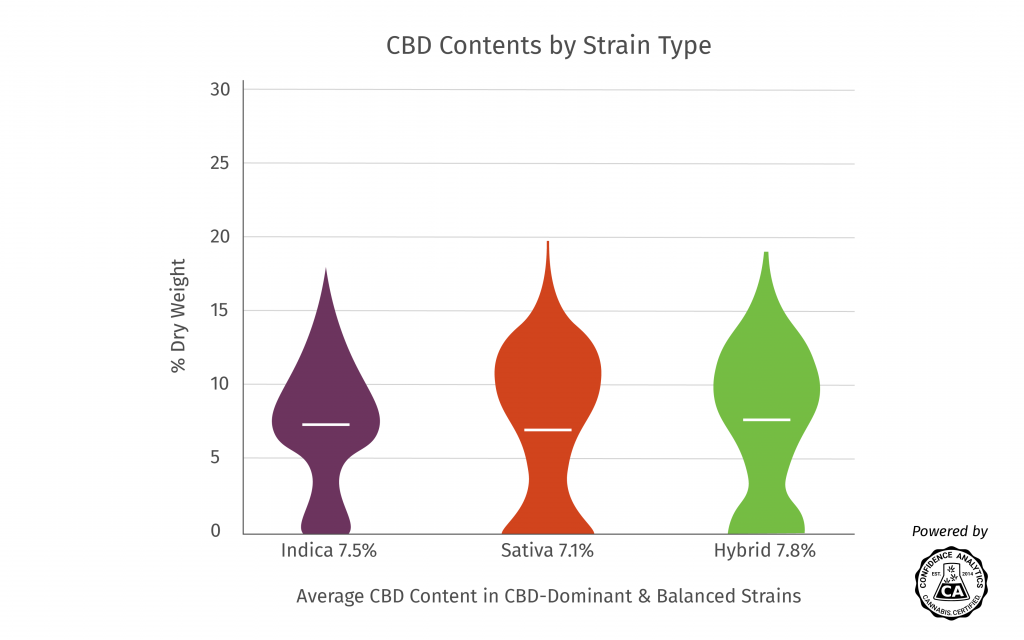

Using data from Confidence Analytics, a state-certified testing lab in Washington, we were able to see how much THC or CBD is produced, on average, by each strain type.

First, let’s take a look at the average abundance of THC in strain samples grouped by their sativa, indica, and hybrid designation on Leafly, for THC-dominant samples only:

Click to enlarge. (Elysse Feigenblatt/Leafly)

As shown in the graphic above, THC-dominant sativa strains on average produced 0.4% more THC than their indica counterparts. So, yes, you could look at that graph and say that sativas produce more THC, but the difference is fairly negligible in terms of statistical significance.

What the graphic does contradict is any claim that THC abundance accounts for the perceived “opposite” effects of indicas and sativas. If that were true, we’d expect hybrids—which are typically seen as a balance of indica and sativa effects, would fall somewhere in between, around 17.5%.

Now let’s see if there are any notable differences in CBD abundance for CBD-containing strains:

Click to enlarge. (Elysse Feigenblatt/Leafly)

Once again, the graph above shows small differences in the average amount of CBD among the three plant types, but not so much that we’d expect to see polar opposite experiences delivered. Indicas, on average, produce 0.4% more CBD than sativas. Again, hybrid strains produced slightly more.

While the bird’s eye view we get with larger sample sizes is helpful in seeing the big picture, you don’t need huge amounts of data to realize that THC and CBD profiles are specific to plant types. Peruse the lab-tested flower on dispensary menus and you’ll see that THC and CBD contents can vary widely, no matter its sativa or indica designation.

How to Shop for Cannabis Without Saying ‘Indica’ or ‘Sativa’

What’s important to you as a consumer shopping for a specific mood is not the shape of the bud or the climate it was grown in. Instead, it has everything to do with potency, dose, and chemical profile (i.e., cannabinoids and terpenes).

For example, if you’re prone to anxiety and looking to avoid an uncomfortable, racy experience, look for a strain with more CBD and less THC. Then dose modestly. If you tell a budtender you hate sativas because they make your thoughts race, they may still hand you a THC powerhouse like White Fire OG simply because it’s not a sativa.

Although it isn’t as simple as grouping strains into the indica-sativa-hybrid triumvirate that has long been our compass while navigating menus, try using potency to guide you. You may find that a strain packing 25% THC isn’t as enjoyable as that very fragrant strain tapping in at 16%, or the balanced THC/CBD variety that provides 10% of each cannabinoid.

RELATED STORY

How Cannabidiol (CBD) Works for Treating Anxiety

Shopping by strain name is also a more reliable way of achieving desirable effects. For example, if you loved the dreamy, blissful euphoria of Granddaddy Purple, you’ll likely have a comparable experience with the next GDP you come across.

Cannabis is a personal experience, and how you select it is, too. This data is meant to give you an alternative perspective on what qualities one should look for in a strain. For many consumers, this level of precision in strain selection is paramount to having a good experience.

Others, well, we’d be happy to sit down with a strain of any variety, any time.

Part 2, Indica vs. Sativa Strains: Which Has More THC & CBD?

Raise your hand if you’ve heard someone say, “Indica strains produce more CBD and sativas have more THC.” Or maybe you’ve heard that claim in reverse. But which is true?

According to cannabis lab testing data, neither is. At least not in any significant way that could explain the perceived difference between these two cannabis types.

In other words, that indica isn’t sleepy because it has more CBD, and that sativa isn’t more energizing because it produced more THC.

But before we get too deep into the numbers, it’s important to first flip a popular notion on its head.

RELATED STORY

CBD vs. THC: What’s the Difference?

Indica & Sativa Designation Isn’t a Reliable Predictor of Effects

It’s possible you’ve noticed that indica and sativa strains look a bit different. One forms chunky, dense buds while the other often grows into airy, fluffy spears. The physical differences between indica and sativa plants allowed each to thrive in different climates, from rugged and cold highlands to tropical regions along the equator.

Click to enlarge. (Amy Phung/Leafly)

Cool, but what does that have to do with how indicas and sativas affect you? Nothing. Exactly.

Ethan Russo, prominent cannabis researcher and neurologist, put it this way:

“The way that the sativa and indica labels are utilized in commerce is nonsense. The clinical effects of the cannabis chemovar have nothing to do with whether the plant is tall and sparse vs. short and bushy, or whether the leaflets are narrow or broad.”

One way we know that this perceived correlation between plant type and effect is flawed is by looking at the chemical profiles—the compounds cannabis produces that contribute to the mood or experience of that strain.

Here, we’ll take a look at the average cannabinoid content of each strain type. Terpenes also play an important role in a strain’s effect, but don’t worry—we’ll get to that in the next installment.

RELATED STORY

Predicting Cannabis Strain Effects From THC and CBD Levels

CBD vs. THC in Indicas and Sativas

Using data from Confidence Analytics, a state-certified testing lab in Washington, we were able to see how much THC or CBD is produced, on average, by each strain type.

First, let’s take a look at the average abundance of THC in strain samples grouped by their sativa, indica, and hybrid designation on Leafly, for THC-dominant samples only:

Click to enlarge. (Elysse Feigenblatt/Leafly)

As shown in the graphic above, THC-dominant sativa strains on average produced 0.4% more THC than their indica counterparts. So, yes, you could look at that graph and say that sativas produce more THC, but the difference is fairly negligible in terms of statistical significance.

What the graphic does contradict is any claim that THC abundance accounts for the perceived “opposite” effects of indicas and sativas. If that were true, we’d expect hybrids—which are typically seen as a balance of indica and sativa effects, would fall somewhere in between, around 17.5%.

Now let’s see if there are any notable differences in CBD abundance for CBD-containing strains:

Click to enlarge. (Elysse Feigenblatt/Leafly)

Once again, the graph above shows small differences in the average amount of CBD among the three plant types, but not so much that we’d expect to see polar opposite experiences delivered. Indicas, on average, produce 0.4% more CBD than sativas. Again, hybrid strains produced slightly more.

While the bird’s eye view we get with larger sample sizes is helpful in seeing the big picture, you don’t need huge amounts of data to realize that THC and CBD profiles are specific to plant types. Peruse the lab-tested flower on dispensary menus and you’ll see that THC and CBD contents can vary widely, no matter its sativa or indica designation.

How to Shop for Cannabis Without Saying ‘Indica’ or ‘Sativa’

What’s important to you as a consumer shopping for a specific mood is not the shape of the bud or the climate it was grown in. Instead, it has everything to do with potency, dose, and chemical profile (i.e., cannabinoids and terpenes).

For example, if you’re prone to anxiety and looking to avoid an uncomfortable, racy experience, look for a strain with more CBD and less THC. Then dose modestly. If you tell a budtender you hate sativas because they make your thoughts race, they may still hand you a THC powerhouse like White Fire OG simply because it’s not a sativa.

Although it isn’t as simple as grouping strains into the indica-sativa-hybrid triumvirate that has long been our compass while navigating menus, try using potency to guide you. You may find that a strain packing 25% THC isn’t as enjoyable as that very fragrant strain tapping in at 16%, or the balanced THC/CBD variety that provides 10% of each cannabinoid.

RELATED STORY

How Cannabidiol (CBD) Works for Treating Anxiety

Shopping by strain name is also a more reliable way of achieving desirable effects. For example, if you loved the dreamy, blissful euphoria of Granddaddy Purple, you’ll likely have a comparable experience with the next GDP you come across.

Cannabis is a personal experience, and how you select it is, too. This data is meant to give you an alternative perspective on what qualities one should look for in a strain. For many consumers, this level of precision in strain selection is paramount to having a good experience.

Others, well, we’d be happy to sit down with a strain of any variety, any time.

How K2 and Other Synthetic Cannabinoids Got Their Start in the Lab

Originally intended for basic neuroscience research, the drugs were ultimately hijacked for illicit recreational use.

Nov 27, 2018

ASHLEY YEAGER

About a decade ago, Clemson University chemist John Huffman started getting calls from law enforcement agencies. Officials from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and other federal agencies wanted to know more about JWH-18, a synthetic cannabinoid bearing Huffman’s initials that he’d created in the lab in 2004 and described in scientific paper in 2005. The compound was turning up in incense, which, rather than being burnt for its scent, was being smoked and was making people sick.

Huffman’s intent, like other scientists who had generated synthetic cannabinoids over the years, was not to create recreational drugs. It was to study the effects of cannabis in the body and how the cannabinoid system works, as well as to develop molecules to image areas of the brain. “The chemistry to make these things is very simple and very old,” Huffman told The Washington Post in 2015. “You only have three starting materials and only two steps. In a few days, you could make 25 grams, which could be enough to make havoc.”

Chemists studying cannabinoids have become unwitting participants in a growing synthetic cannabinoid drug epidemic with no signs of stopping.

And havoc it’s been. The number of emergency room visits as a result of smoking synthetic cannabinoids, often laced with other drugs, is in the thousands annually, and poison control centers have seen a spike in calls about the compounds in recent years, with nearly 8,000 in 2015. Called K2 or Spice, these synthetic compounds first started sickening Americans in 2008, with illnesses reported in Europe before the drugs reached the US. In 2011, the DEA made it illegal to sell JWH-018 and four related compounds or products that contained them, but that hasn’t kept new synthetic cannabinoids from emerging on the illegal drug market and leading to life-threatening overdoses.

See “Synthetic Cannabinoid K2 Overdoses Are Rampant. Here’s Why.”

Synthetic cannabinoids are not the first substances concocted in a lab and then hijacked for illicit use. The same thing happened to ecstasy, also called MDMA, and LSD. The difference is that the structure of the cannabinoid system makes it receptive to a diverse set of compounds, setting it up as an easier target for an array of synthetic drugs compared to other systems, says Northeastern University chemical biologist Alexandros Makriyannis. This means chemists studying cannabinoids have become unwitting participants in a growing synthetic cannabinoid drug epidemic with no signs of stopping. Makriyannis himself generated synthetic cannabinoids that served as blueprints for those later sold illegally. “It’s terrible,” he says.

The history of synthetic cannabinoids

The first scientists to study cannabis and create synthetic cannabinoids back in the 1940s had no idea that cannabinoid receptors even existed, nor did they know how marijuana’s phytochemicals interacted with other molecules in the body. Back then, the research seemed a bit more straightforward. Alexander Todd of the University of Manchester and Roger Adams from the Noyes Chemical Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign were building analogs to cannabis using organic compounds called terpenoids to try to tease apart the bioactive elements of the drug and the effects they had on the body. These two were the first to produce synthetic molecules that mimicked the effects of cannabis and to show that the compounds they made could have even greater physiological effects than marijuana.

Then, in the 1960s and 1970s, Raphael Mechoulam, a chemist at Hebrew University in Israel, isolated THC, the active ingredient in marijuana. He and others subsequently started to make synthetic compounds based on the structure of THC. The first scientists to study cannabis and create synthetic cannabinoids back in the 1940s had no idea that cannabinoid receptors even existed, nor did they know how marijuana’s phytochemicals interacted with other molecules in the body. Back then, the research seemed a bit more straightforward. Alexander Todd of the University of Manchester and Roger Adams from the Noyes Chemical Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign were building analogs to cannabis using organic compounds called terpenoids to try to tease apart the bioactive elements of the drug and the effects they had on the body. These two were the first to produce synthetic molecules that mimicked the effects of cannabis and to show that the compounds they made could have even greater physiological effects than marijuana.

At the same time, scientists at drug companies started to used these researchers’ data and do their own experiments to attempt to make non-opioid–based pain medicine. Among the products created was Nabilone, an FDA-approved drug first developed by Eli Lilly that is designed to reduce brain signals that spur nausea and vomiting, typically in response to cancer treatments such as chemotherapy. Pfizer was also in on the work to make marijuana-based painkillers, which led to what the company called non-classical cannabinoids. Pharmaceutical developers there made many of them, all of which had different effects on the body, depending on slight structural modifications.

See “Your Body Is Teeming with Weed Receptors”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse organized a meeting in 1986 of many of the leading cannabinoid researchers at the time to discuss what was known and still unknown about THC and its analogs. Not long after, a few of the scientists at the meeting, including Makriyannis, independently identified the structureof a nerve cell receptor, now called CB1, which responded to THC. It was the first cannabinoid receptor to be documented. A few years later, other researchers identified an additional cannabinoid receptor, CB2. CB2 is fairly rare in the mammalian brain, unless there’s been brain inflammation, neurodegeneration, or cancer, Makriyannis says.

With information on cannabinoid receptors in hand, scientists rushed to create hundreds of synthetic cannabinoids, many by Huffman, to push the system and see how it worked.

From the lab to the street

The efforts to create new synthetic cannabinoids took place mainly in the 1990s and early 2000s—the same time internet access was beginning to become mainstream and researchers started publishing their results online. “When research on synthetic cannabinoids first started, not many people had access to the research journals with the chemical structures of the compounds,” Jenny Wiley, a behavioral pharmacologist who studies cannabinoids at RTI International, tells The Scientist.

As journals went online, she says, chemists looking to make illicit drugs could access not only the chemical compounds of synthetic cannabinoids, but also the data on their potency. In fact, compounds such as Huffman’s might have been hijacked first because he reported both the chemical formula and the potency together in academic journals, Wiley speculates. On the other hand, many of the drug companies’ compounds were patented, and the patents probably did not contain information on the physiological effects of the compounds.

“These rogue chemists were taking the recipes of these synthetic cannabinoids right out of the journals,” says Barbara Carreno, a public affairs officer at the DEA. Wiley suspects the street drugs were first generated in China, but no one knows for sure their precise origin. DEA officials first started to notice the drugs turning up in raids they were doing of shipping containers coming from Europe. There had been reports of use of the drugs in Europe in 2005, but the compounds hadn’t hit the US market until 2008. When the DEA tested the compounds, Huffman’s JWH-18 showed up first, then JWH-250 and JWH-073. “At the time, he was irate that rogue chemists were hijacking his work to make street drugs,” Carreno says.

A public health calamity

There’s not much data on how much money is spent each year on synthetic cannabinoid drug sales, but the DEA does record the top 25 most frequently identified drugs. In 2017, methamphetamine topped the charts with 347,807 drug reports from labs testing compounds in cases of overdoses or drug raids and seizures. Cannabis/THC was second at 344,167 reports. Two synthetic cannabinoids made the top 25 list: FUB-AMB, with 8,108 reports and 5F-ADB with 6,951 reports.

These rogue chemists were taking the recipes of these synthetic cannabinoids right out of the journals.

—Barbara Carreno, DEA

It’s mostly 20- to 30-year-old men, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who turn to synthetic cannabinoids as an alternative to marijuana. Some products are “legal” to smoke, if the substances aren’t yet banned by the DEA, and because the ingredients continue to change constantly, they are less likely to be detected in drug screens that may be required for jobs, included in drug addiction treatment plans, and used by law enforcement.