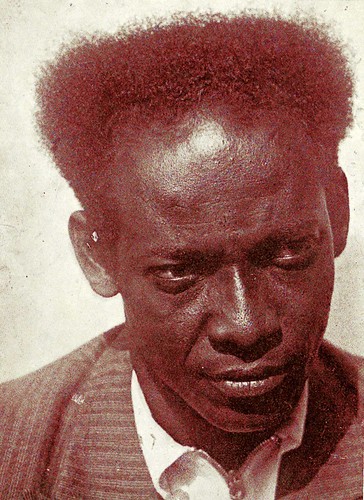

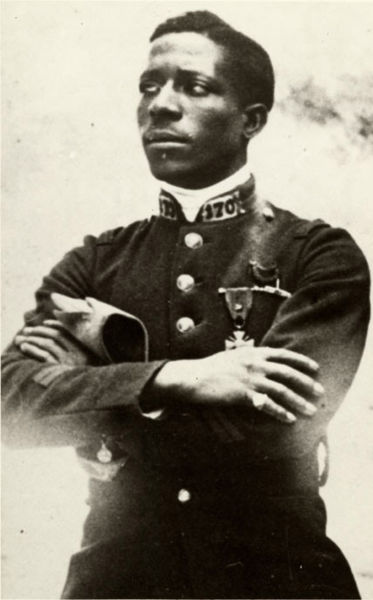

EUGENE JACQUES BULLARD

9 Oct. 1894 - 12 Oct. 1961

First Black Fighter Pilot

America’s first black aviator did not fly for the country of his birth America, but for his adopted country of France. A country for which he was severely wounded and received many medals for valor. Gene himself was a man who hesitated to speak of himself but one who stood on the principles of honesty and integrity. He treated everyone as he wished to be treated and because of that he was very well liked. He lived by the belief that all men were created equal and should be treated accordingly.

Eugene Jacques Bullard was born on October 9, 1894, in Columbus Georgia, the seventh of ten children born to William (Octave) Bullard, a black from Martinique, and Josephine ("Yokalee") Thomas, a Creek Indian. Eugene’s father could trace their family roots as far back as the American Revolution. His family came from Martinique, an Island in the West Indies and spoke French as an everyday language. They arrived in America as slaves when their French owners fled the Haitian revolution. His mother died at age thirty three when Eugene was only five, leaving his father to raise him. Eugene said his father was an educated man who worked hard as a laborer and treasured his hours at home telling his children tales from the books he read. It was his father’s influence and those stories that would shape Eugene’s direction in life.

Eugene, divided by family loyalty and a quest for freedom, tearfully left his Columbus, Georgia home in 1902 at the tender age of eight. The catalyst for his early departure was the near unjust lynching of his father. The latter incident brought to Eugene’s mind the words his father had spoken earlier to him: in France a man is accepted as a man regardless of the color of his skin. He left home seeking this paradise, this France.

Because of his fourth grade education, and his young age, he wandered throughout the southeastern United States, mostly at night to avoid hostile whites, searching for the ways and means to travel to France. He stayed with Gypsies for a year and learned how to handle horses and did a little racing. He found he was skilled as a jockey and won a number of unofficial races all the time putting his money away in the hopes of traveling to France. He worked his way towards the seaport in Norfolk, Virginia and after four years of wandering and working at odd jobs to stay alive, he stowed away on a German ship bound for Aberdeen, Scotland-he was 12 years old.

He soon moved from Aberdeen to Glasgow and worked as a lookout man for gamblers and earned pennies as a whistler. He stayed in Glasgow for five months then moved to the larger seaport town of Liverpool, England. There he worked as a longshoreman and earned six shillings a day. He was still very young and light and the work soon wore him down. He found work as a helper on a fish wagon and doing odd jobs. Later he worked at an amusement park. He earned extra money by dodging balls people threw at him, money that allowed him free time, which he spent at the local gym.

Eugene made it his business to be at Chris Baldwin’s Gymnasium daily when he wasn’t working. Around the gym he did everything the owner wanted and his quick, warm smile and sunny nature made him popular and he made friends with most of the boxers. Soon he was being coached and worked in the ring with anyone who the manager asked him to. He started as a bantam weight but within a year of lifting weights and working out he worked up to light weight. He was just sixteen years old.

After a successful ten round fight against Billy Welsh he was noticed by and became a protégé of the renowned boxer the Dixie Kid. Eugene quickly developed as an aspiring fighter, winning bouts in England and France as a welterweight. When he finally got his bout in France, boxing in Paris at the Elysee Montmartre, it was November 28, 1913. From the moment he first set foot in France he knew this was the place he belonged, and that first visit cemented his long-held aspiration of moving to Paris.

Not long after he returned to Liverpool, Gene, with the help of the Dixie Kid, joined a traveling act called "Freedman's Pickaninnies." They sang and danced and made people laugh with their jokes and slapstick comedy. He signed on because one of their stops was scheduled to be at the Bal Tabarin in Paris.

Soon after joining, the troupe began a tour of the continent where they amused audiences all over Europe and Russia. After Russia, they performed at the Winter Garden in Berlin, Germany, and finally Paris. When Freedman’s Pickaninnies left Paris Eugene was not with them. The chance to live in France was nothing less than a fulfillment of a dream for Bullard. He settled himself in Paris, found a place to stay and was soon employed back in the world of boxing.

Gene easily picked up languages and quickly learned to speak French quite well and picked up a little German when he performed in Berlin. His fellow boxers who could not speak French used Gene as an interpreter and he was soon setting up their boxing matches. Eugene described his fellow boxers as generous, kind people who showed their appreciation for his help. He was soon making more money then he previously had in England.

Eugene Bullard was a very happy man who quickly discovered that his father had been right about France. He expressed his feelings like this, "it seems to me that the French democracy influenced the minds of both white and black Americans there and helped us all to act like brothers as near as possible…It convinced me too that God really did create all men equal, and it was easy to live that way."

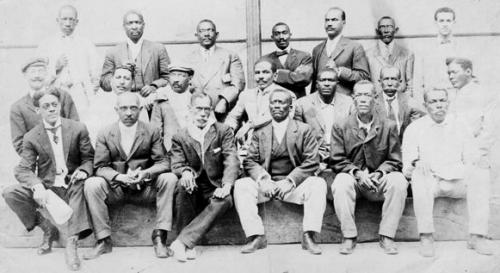

By August 1914 the world was plunged into war and the French nation sustained a half-million casualties before the year was out. A number of Eugene’s friends were on the casualty list but Bullard, not yet 19 years old, was too young to be accepted to fight for his adopted country. His love for his new country and his departed friends spurred him on to join the French Foreign Legion. Bullard joined his fellow American expatriates in the French Foreign Legion on 9 October, his 19th birthday. He went to the Recruiting Bureau on Boulevard des Invalides, Paris and enlisted. He was sent to the Tourelles Barracks on Avenue Gambetta in Paris for training. Training was tough but Eugene’s physical conditioning for

boxing made it a little easier than many of his fellow recruits.

After five weeks of training he was assigned to the Moroccan Division, Third Marching Regiment, which he said contained 54 different nationalities. Eugene Bullard and his comrades were sent to the Somme front where 300,000 Frenchmen were lost by the end of November. Bullard and his fellow legionnaires did most of their fighting with the bayonet, if they weren't cut down by machine gun fire first. Battle casualties were very heavy.

As much a warrior as an adventurer and boxer, Eugene participated in some of the most heavily contested battles of 1914 through 1916. Besides the battles of the Somme front he participated in battles at Artois Ridge, Mont-Saint-Eloi, and they assaulted the German positions at Souchez and Hill 119.

Because of German atrocities Legionnaire officers ordered that no prisoners were to be taken, so the Germans retaliated by declaring that all captured legionnaires were to be shot. Because of this and the hard fighting by May 9, 1915 they would lose so many men in Eugene’s Third Marching Regiment that it would be dissolved and the second and third regiments would combine to form the First and Second Regiments. For example at the Battle of Artois Ridge 4,000 men participated but only 1,700 survived. Bullard's company lost some 80 percent of its strength with only 54 of its 250 men left standing.

Occasionally before a battle each man was given, as a means of fortifying his fighting spirit, a drink of Tafia, a strong drink that was designed to spur a man's courage. Bullard wrote of it, "you wanted to fight, sing, dance, or anything. Oh, boy, what a wonderful feeling."

Bullard was sent into battle again during the September 1915, Champagne Offensive. The battle and the rain started on the 25th at 4 A.M. and went through the 28th without a let up. The infantry had to bear the brunt of the battle as usual because there were no tanks in the Battle of Champagne. Five hundred men began the battle, but at the first evening's roll call only 31 remained - a 94 percent casualty rate. Eugene received what he called "a little head wound" during the battle. "In the Legion, as long as you could walk or your trigger finger is not out of commission, you are good for the service." Bullard’s regiment had lost many of their men and seemed to bear the brunt of every offensive. The unit was basically disbanded in October and Bullard was sent to join the 170th Infantry, the "Swallows of Death." This was the unit from which Bullard took the name, The Black Swallow of Death. The German nickname for the unit was "The Chimney Swifts of Death."

Verdun became Bullard's next battlefield. The 170th marched for three days and three nights until, on the 21st of February, 1916, they arrived early in the morning in the region of Verdun. Bullard said it was obvious they had arrived in hell. He said, "I thought I had seen fighting in other battles but no one has ever seen anything like Verdun – not ever before or ever since."

The Germans codenamed Verdun Operation Execution Place. It was aptly named. In the 10 months of Verdun more than 250,000 died, 100,000 were missing and 300,000 had been gassed or wounded. On March 5th 1916 Bullard received the wounds that removed him from the ground war and subsequently awarded The Croix de Guerre and Medaile Militaire.

While he was convalescing in Lyons, the third largest city in France, from his wounds (they thought he would never walk again) Eugene gained his first bit of fame when he was interviewed by Will Irwin of The Saturday Evening Post. Since he was no longer fit for duty with the infantry, Eugene was afforded the opportunity to join the French Flying Corp. An American friend of Bullard’s bet him two thousand dollars that he could not get into aviation and become a pilot. Eugene, perhaps bolstered by the challenge, soon earned his wings from the aviation school in the city of Tours on May 5, 1917, and just as promptly collected his two thousand dollars. This made Bullard the very first black fighter pilot in history.

Eugene was sent to several more flying schools and learned to fly the Caudron G-3 and the Caudron G-4. It took Eugene much longer than other students to be assigned to the front. Inquires were made because France needed pilots and Eugene seemed to be held back for no good reason. After that he was soon assigned to the now famous Lafayette Escadrille, Spad 93 flying Spad V11s and Nieuports. He said, "I was treated with respect and friendship - even by those from America. Then I knew at last that there are good and bad white men just as there are good and bad black men."

Corporal Eugene Bullard painted a red bleeding heart pierced by a knife on the fuselage of his Spad. Below the heart was the inscription "Tout le Sang qui coule est rouge!" Roughly translated it says "All Blood Runs Red.

Eugene’s first mission was on September 8, 1917. He was flying a Nieuport that he called a real sweetheart, on a reconnaissance mission over the city of Metz. He went up that day and from then on never missed a mission. Bullard claimed two "kills," but he received confirmation on only one. One "kill" remained unverified because the German Fokker fell behind enemy lines. No one doubted he had shot the aircraft down. His mechanics found seventy-eight bullet holes in his plane. His second kill was in November 1917, and there was no doubt about this one. He shot down a German Pfalze after the pilot went into a classic Immelmann turn, flying nose up and then turning backward, to attempt to come in from behind. Bullard ducked into a cloud bank and emerged below and to the right of his foe where he pulled in behind him and shot the German down. This one was confirmed.

George Dock recalled him to be a humorous, brave and self-reliant man. Charles Kinsolving noted that Bullard had no fear.

When the United States entered World War I Eugene Bullard wanted to transfer to his country’s air force. By that time he had fought for over three years in the war and been wounded four times, twice in the battle of Verdun. He had spent eight months in hospitals recovering from war wounds, earned medals for valor, and was now a military pilot with confirmed kills. As a pilot and an American he was invited to transfer to the American Air Force with the promise of being promoted. After passing the physical, when many other American pilots departed to fight with fellow Americans, Bullard’s application was ignored for the duration of the war.

On November 11, 1917, Bullard was transferred from the French Air Service and sent to his old unit the 170th Infantry, where he performed non combat jobs in one of the service companies until the end of the war. Eugene wrote in his auto biography that he had a quarrel in a café with a French Captain who insulted him because of his race. His friends however, tell another story. One night when he was returning late from a 24 hour leave in Paris, he tried to enter a covered military truck to catch a ride. He was pushed out onto a rain-soaked, muddy road. He tried to enter again and was booted in the chest. Bullard, angry, grabbed the boot, pulled its owner from the truck, and knocked him backward into a ditch. The man turned out to be a French Lieutenant. Regardless of circumstance, an assault on an officer was a very serious offense, but Bullard's heroic record and wounds saved him from a court martial - he was simply returned to his old infantry unit.

In October, 1919, Eugene Bullard was discharged from the armed forces of France, a national hero of significant standing. He decided to remain in Paris and soon married a French Countess and fathered three children, one boy and two girls. The boy died soon after his birth from double pneumonia. His marriage failed after his wife inherited money and wanted Eugene to retire and be with her socially full time. But he loved people and his life the way it was, so they eventually went their separate ways. Both were of the Catholic faith and did not believe in divorce. When his former wife died six years after their separation, Gene took custody of his two daughters.

At the nightclub, Le Grand Duc, where he was the host and part owner, Bullard entertained the likes of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gloria Swanson and England's Prince of Wales. He opened his own club soon after his marriage which soon became one of Paris’ most famous entertainment spots for singers and musicians of the time.

Then, in 1939, war once again threatened the nation Eugene once more answered the call to duty. In July 1939, he joined the French underground and resistance movement. He spoke three languages including German, and readily agreed to honor a request to spy for France. The Germans arrogantly felt that no black man could properly understand their language, so Bullard was quite successful in this endeavor. Eugene worked occasionally with the famous French spy Cleopatra Terrier.

But as Paris was being overrun by the German army, Gene fled the city with his daughters. Upon arriving in Orleans he joined some uniformed troops who were defending the city. When the group Bullard was with came under heavy attack, his dozen or so compatriots were killed and he was badly wounded.

Rather than allow him to be captured and interrogated by the Gestapo, his espionage partner, Kitty, was able to successfully doctor his wounds and smuggled him to Spain with his daughters. Later he was medically evacuated to the United States.

Fully recovered in New York City and joined by his daughters Eugene settled down to rebuild his life. He was thrilled to again see America, and he soon found work as an elevator operator in Rockefeller Center. It was the job he would hold until he retired.

Perhaps through disinterest or uncaring, America never recognized or realized the legacy of the brave and noble Corporal Eugene Bullard. But France never forgot.

In 1954, the French government requested his presence to help relight the Eternal Flame of the Tomb of the Unknown French Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Eugene, along with two white French men, was presented the honor of relighting the flame. Yet, when he returned to America, it failed to recognize him as the hero he was.

In 1959 at age 65, he was named Knight of the Legion of Honor in a lavish ceremony in New York City. Dave Garraway interviewed him on the Today Show, still America did nothing to acknowledge this honor or acknowledge his place in history.

President-General Charles de Gaulle of France, while visiting New York City, publically and internationally embraced Eugene Bullard as a true French hero in 1960.

On 12 October, 1961, after suffering a long illness due to the wounds he received, Eugene Jacques Bullard passed away. But, again, France did not forget. On 17 October, with the tri-color of France draping his coffin, he was laid to rest with full honors by the Federation of French War Officers at Flushing Cemetery in New York.

When Eugene was awarded the Legion of Honor several years before his death, he tried to explain his feelings about both France and America. He said, "The United States is my mother and I love my mother, but as far as France is concerned, she is my mistress and you love your mistress more than you love your mother—but in a different way."

The first black fighter pilot in the world, the Black Swallow of Death, a man who had seen much war, was thus given final honors by the country he had loved and served during two world wars. On August 23, 1994, seventy seven years after Bullard’s American flight physical, the USAF posthumously commissioned him a Lieutenant. *

Source:

http://www.au.af.mil/au/cadre/aspj/apjinternational/apj-s/2005/3tri05/chivaletteeng.html

ffice

ffice