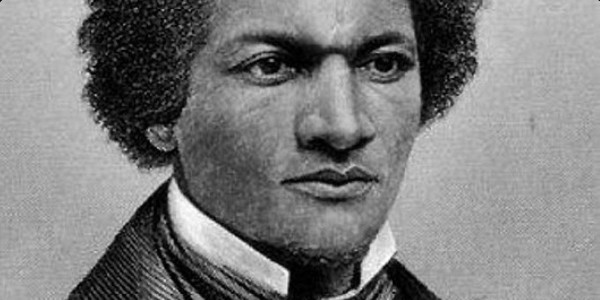

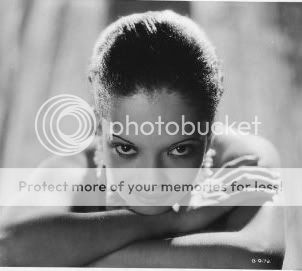

Nina Mae McKinney

Originally from South Carolina, 13-year-old Nannie Mayme McKinney renamed herself and moved with her mother to New York City in 1925 to become a star. Film director King Vidor discovered the "third chorus girl from the right" in the Broadway musical Blackbirds of 1928 and cast her as the lead of his film Hallelujah. That role landed "the black Garbo" a five-year contract, launching her reputation as Hollywood's original black "love goddess," setting the stage for Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne to follow.

Nina Mae McKinney (June 13, 1912 – May 3, 1967) was an American actress who worked internationally in theatre, film and television after getting her start on Broadway and in Hollywood. Dubbed "The Black Garbo" in Europe, she was one of the first African-American film stars in the United States and was one of the first African Americans to appear on British television.

Nina Mae McKinney was born in 1912 in the small town of Lancaster, South Carolina, to Hal and Georgia McKinney. Her parents moved to New York for work during the Great Migration, and left their young daughter with her Aunt Carrie. McKinney ran errands and learned to ride a bike. Her first public performances involved stunts on bikes, where her passion for acting was clear. She acted in school plays in Lancaster and taught herself to dance.

McKinney left school at the age of 15, moving to New York to pursue acting, and was reunited with her parents. Her debut on Broadway was dancing in a chorus line of the hit musical Blackbirds of 1928. This show starred Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and Adelaide Hall. The musical opened at the Liberty Theater on May 9, 1928 and became one of the longest-running and most successful shows of its genre on Broadway,.

Her performance landed McKinney a leading role in a film. Looking for a star in his upcoming movie, Hallelujah!, the Hollywood film director King Vidor spotted McKinney in the chorus line in Blackbirds. He said, "Nina Mae McKinney was third from the right in the chorus. She was beautiful and talented and glowing with personality." And that’s what rocketed her into the world of acting and Hollywood. In Hallelujah (1929), McKinney was the first African-American actress to hold a principal role in a mainstream film; it had an African-American cast. Vidor was nominated for Oscar for his directing of Hallelujah and McKinney was praised for her role. When asked about her performance, Vidor told audiences "Nina was full of life, full of expression, and just a joy to work with. Someone like her inspires a director."

After Hallelujah!, McKinney signed a five-year contract with MGM – the first African-American performer to sign a long-term contract with a major studio – but the studio seemed reluctant to star her in feature films. Her most notable roles during this period were in films for other studios, including a leading role in Sanders of the River (1935), made in the UK, where she appeared with Paul Robeson. After MGM cut almost all her scenes in Reckless (1935), she left Hollywood for Europe. She acted and danced, appearing mostly in stage roles and cabaret.

After World War II, McKinney returned to Europe, living in Athens, Greece until 1960, when she returned to New York. Time passed after McKinney's starring role, and work was hard to come by because not many movies were interracial, and Hollywood was a difficult place for African American actors, actresses, directors, writers, and producers. Especially for African American women, breaking out into a major role was hard because there weren’t many choices for roles a woman of color could play. Even though she had the looks, Hollywood was afraid to make her into a glamorized like white actresses of the time. It was two years after Hallelujah that McKinney returned to the silver screen as a supporting actress in Safe in Hell, directed by William A. Wellman. In this movie, McKinney played the role of a waitress who befriends an escaped New Orleans hooker.

Because of the prevalence of racism not only in the entertainment industry but also throughout the United States in general, many African-American actors and actress escaped the United States for countries throughout Europe. In Europe McKinney was nicknamed the “Black Garbo,” because of her striking beauty more than resemblance to the Swedish actress, Greta Garbo.

In December 1932, she went to Paris and appeared as a cabaret entertainer in nighttime hot spots or restaurants. One of these was called Chez Florence. In February 1933, she starred in a show called Chocolate and Cream in the Leicester Square Theatre in London. She even went as far as Athens to pursue her career. After touring for a while, she returned to London in 1934 to appear in a British film titled Kentucky Minstrels, (released in the United States as Life is Real.) The film was one of the first British to feature African American actors. Film Weekly said about McKinney, "Nina Mae McKinney, as the star of the final spectacular revue, is the best thing in the picture—and she, of course, has nothing to do with the 'plot'."

In the years following her role in Kentucky Minstrels, McKinney remained in England and worked on some more odd things. . She also sang the popular song "Dinah" during Music Hall - a radio broadcast show.

She got another big break, and received a starring role in her first film in six years. In 1935, she appeared in Sanders of the River directed by Alexander Korda. McKinney and Robeson, her co-star, were told that this film would portray African Americans in a positive light, that was even one of the conditions that Robeson would be in the movie. But after it was re-edited without the knowledge of McKinney and Robeson, as well as the other African American actors, it highlighted the power of the British Empire around the world.

Things did turn around for McKinney, and she remained in London. In 1936 she was given her own television special on BBC which showcased her singing. In 1937, she had a role in Ebony, alongside the African-American dancer Johnny Nit. Following that performance, she also made an appearance in Dark Laughter with the Jamaican trumpet player Leslie Thompson. McKinney was given rave reviews for her singing "Poppa Tree Top Tall" in a documentary in 1937. This is the only surviving record of her performances in British television pre-World War II. Once war broke out in Europe, she returned home to the United States.

After returning to the United States, McKinney starred in some "race films" intended for African-American audiences. These include Gang Smashers Gun Moll (1938) and The Devil’s Daughter (1939), which was filmed in Jamaica. She can be heard singing an excerpt of The Devil’s Daughter soundtrack on the album Jamaica Folk Trance Possession 1939-1961 album. She took a break for some time, and then tried to make a comeback in Hollywood. She took roles in some smaller films, having to accept stereotypical roles of maids and whores. For example, in 1944 she appeared alongside Merle Oberon, playing a servant girl in the film Dark Waters. In 1951, McKinney made her last stage appearance, playing Sadie Thompson in a summer stock production of Rain.

spent her final years living in New York City. On May 3, 1967, she died of a heart attack at the age of 53.

In 1978, McKinney received a posthumous award from the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame for her lifetime achievement.

In 1992, the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center in New York City replayed a clip of Nina Mae McKinney singing in Pie, Pie Blackbird (1932) in a combination of clips called Vocal Projections: Jazz Divas in Film.

The film historian Donald Bogle discusses McKinney in his book titled Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies And Bucks—An Interpretive History Of Blacks In American Films (1992). He recognizes her for inspiring other actresses and passing on her techniques to them. He wrote, “her final contribution to the movies now lay in those she influenced."

A portrait of McKinney is displayed in her hometown of Lancaster, South Carolina at the courthouse’s "Wall of Fame."

SOURCES: The Root; and Wikipedia