You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Official: Police Reform Thread

- Thread starter QueEx

- Start date

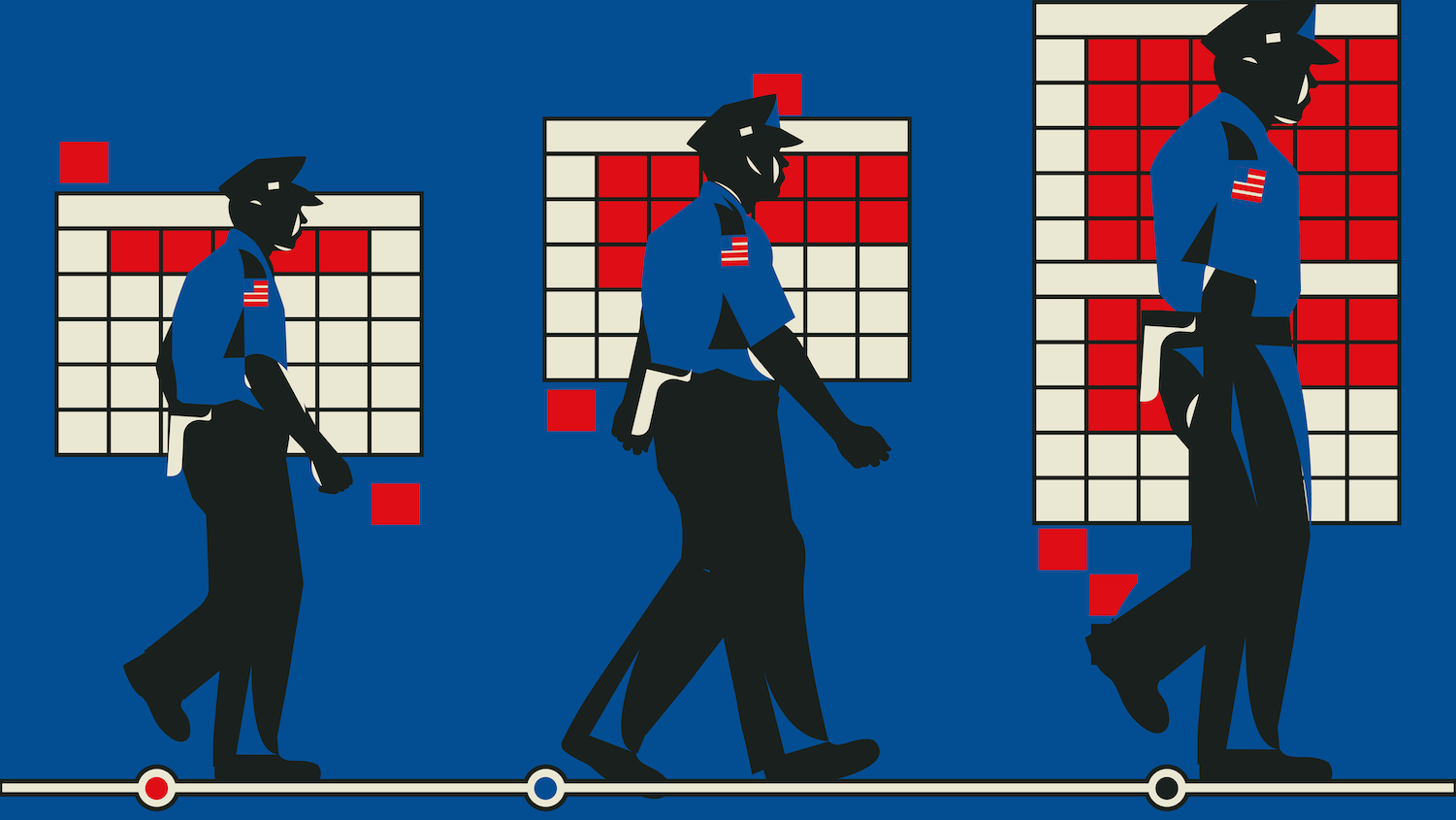

Five Ideas for a More Sensible Approach to Police Reform

The Manhattan Institute

Rafael A. Mangual

June 12, 2020

In the wake of understandable public outrage sparked by the troubling death of George Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police, federal lawmakers find themselves under considerable pressure to advance proposals aimed at improving police-community relations. While there are good reasons to be skeptical of many of the most popular reforms being advanced, members of Congress should consider reforms aligned with five broad principles:

1. Recruit an increasingly more professional workforce

Particularly as police agencies across the country report recruiting shortages and retention issues, the need to fill police ranks with high-caliber officers is paramount. The U.S. armed forces provide a potential model. Potential military recruits with four-year and advanced degrees are able to join as commissioned officers, which often translates to a quicker and more-promising promotional track. Police agencies should explore a similar pilot program, which, by offering a quicker and more reliable track to investigative and/or managerial roles to college and advanced degree-holders, can attract high-caliber recruits.

2. Train with an emphasis on legal knowledge

Law enforcement officers must make difficult decisions in the field, which often require the application of legal doctrines to the facts available to them in real time. Minimizing—through more extensive, and continuous, legal training—instances in which police err in making these decisions will benefit police and citizens alike. And encouraging officers to, when feasible and advisable, explain events to those they deal with, as those events unfold, may help ease the tensions inherent in intrusive interactions.

3. Reveal activity with broader adoption of body-worn cameras

The wider adoption of body-worn cameras (BWCs) is an idea that enjoys high levels of public support. Though in use across the country for many years, BWCs have not been universally adopted. As of 2016, just under half of U.S. police agencies had acquired BWCs. Though police critics often propose cameras as a way to moderate police misbehavior, the available evidencedoes not suggest that BWCs will reduce police uses of force. It does, however, seem to suggest that BWCs reduce frivolous citizen complaints, while also aiding in criminal investigations and prosecutions.

4. Constrain with express authorization for no-knock raids

The execution of search and arrest warrants is an exceptionally important, and sometimes very dangerous, task for American police—particularly given the proliferation of both legal and illegal gun ownership in the United States. However, troubling stories of children injured by errant flashbangs, and of private citizens firing on police under the mistaken impression that they were unlawful intruders, illustrate the dangers involved in no-knock raids—raids in which police forcefully enter a dwelling (often late at night or in the early morning) without first knocking and announcing themselves. One potential reform in this area would be to require commanding officers to submit a written declaration, based on actionable intelligence of a potential threat to officers, that such a raid is the most prudent tactical option.

5. Document with better and more-consistent data collection

Crucial to both the public’s understanding of law enforcement, and the betterment of policing practices, is the availability of reliable data that policymakers and analysts can assess in their attempts to answer important questions. Among those questions: the extent to which violent crimes are committed by offenders out on bail, and how resource deployment decisions affect crime in hot spots. With CompStat, the New York City Police Department illustrated how data can help inform important internal decisions. So, too, can more data better inform the analyses of those studying issues of public safety.

______________________

Rafael A. Mangual is a fellow and deputy director for legal policy at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal. Follow him on Twitter here.

www.manhattan-institute.org

www.manhattan-institute.org

The Manhattan Institute

Rafael A. Mangual

June 12, 2020

In the wake of understandable public outrage sparked by the troubling death of George Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police, federal lawmakers find themselves under considerable pressure to advance proposals aimed at improving police-community relations. While there are good reasons to be skeptical of many of the most popular reforms being advanced, members of Congress should consider reforms aligned with five broad principles:

1. Recruit an increasingly more professional workforce

Particularly as police agencies across the country report recruiting shortages and retention issues, the need to fill police ranks with high-caliber officers is paramount. The U.S. armed forces provide a potential model. Potential military recruits with four-year and advanced degrees are able to join as commissioned officers, which often translates to a quicker and more-promising promotional track. Police agencies should explore a similar pilot program, which, by offering a quicker and more reliable track to investigative and/or managerial roles to college and advanced degree-holders, can attract high-caliber recruits.

2. Train with an emphasis on legal knowledge

Law enforcement officers must make difficult decisions in the field, which often require the application of legal doctrines to the facts available to them in real time. Minimizing—through more extensive, and continuous, legal training—instances in which police err in making these decisions will benefit police and citizens alike. And encouraging officers to, when feasible and advisable, explain events to those they deal with, as those events unfold, may help ease the tensions inherent in intrusive interactions.

3. Reveal activity with broader adoption of body-worn cameras

The wider adoption of body-worn cameras (BWCs) is an idea that enjoys high levels of public support. Though in use across the country for many years, BWCs have not been universally adopted. As of 2016, just under half of U.S. police agencies had acquired BWCs. Though police critics often propose cameras as a way to moderate police misbehavior, the available evidencedoes not suggest that BWCs will reduce police uses of force. It does, however, seem to suggest that BWCs reduce frivolous citizen complaints, while also aiding in criminal investigations and prosecutions.

4. Constrain with express authorization for no-knock raids

The execution of search and arrest warrants is an exceptionally important, and sometimes very dangerous, task for American police—particularly given the proliferation of both legal and illegal gun ownership in the United States. However, troubling stories of children injured by errant flashbangs, and of private citizens firing on police under the mistaken impression that they were unlawful intruders, illustrate the dangers involved in no-knock raids—raids in which police forcefully enter a dwelling (often late at night or in the early morning) without first knocking and announcing themselves. One potential reform in this area would be to require commanding officers to submit a written declaration, based on actionable intelligence of a potential threat to officers, that such a raid is the most prudent tactical option.

5. Document with better and more-consistent data collection

Crucial to both the public’s understanding of law enforcement, and the betterment of policing practices, is the availability of reliable data that policymakers and analysts can assess in their attempts to answer important questions. Among those questions: the extent to which violent crimes are committed by offenders out on bail, and how resource deployment decisions affect crime in hot spots. With CompStat, the New York City Police Department illustrated how data can help inform important internal decisions. So, too, can more data better inform the analyses of those studying issues of public safety.

______________________

Rafael A. Mangual is a fellow and deputy director for legal policy at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal. Follow him on Twitter here.

MI Responds: Five Ideas for a More Sensible Approach to Police Reform

In the wake of understandable public outrage sparked by the troubling death of George Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police, federal lawmakers find

www.manhattan-institute.org

www.manhattan-institute.org

Mapping Police Violence

Law enforcement agencies across the country are failing to provide us with even basic information about the lives they take. So we collect the data ourselves.

Mapping the Violence

Law enforcement agencies across the country have failed to provide us with even basic information about the lives they have taken. And while the recently signed Death in Custody Reporting Act mandates this data be reported, its unclear whether police departments will actually comply with this mandate and, even if they do decide to report this information, it could be several years before the data is fully collected, compiled and made public.

We cannot wait to know the true scale of police violence against our communities. And in a country where at least three people are killed by police every day, we cannot wait for police departments to provide us with these answers.

The maps and charts on this site aim to provide us with the answers we need. They include information on:

1,106 known police killings in 2013,

1,050 killings in 2014,

1,050 killings in 2014,

1,103 killings in 2015,

1,071 killings in 2016,

1,093 killings in 2017,

1,142 killings in 2018 and

1,098 killings in 2019.

95 percent of the killings in our database occurred while a police officer was acting in a law enforcement capacity. Importantly, these data do not include killings by vigilantes or security guards who are not off-duty police officers.

This information has been meticulously sourced from the three largest, most comprehensive and impartial crowdsourced databases on police killings in the country:

* the U.S. Police Shootings Database; and * KilledbyPolice.net.

We've also done extensive original research to further improve the quality and completeness of the data; searching social media, obituaries, criminal records databases, police reports and other sources to identify the race of 90 percent of all victims in the database.

We believe the data represented on this site is the most comprehensive accounting of people killed by police since 2013. A recent report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated approximately 1,200 people were killed by police between June, 2015 and May, 2016. Our database identified 1,106 people killed by police over this time period. While there are undoubtedly police killings that are not included in our database (namely, those that go unreported by the media), these estimates suggest that our database captures 92% of the total number of police killings that have occurred since 2013. We hope these data will be used to provide greater transparency and accountability for police departments as part of the ongoing campaign to end police violence in our communities.

Definitions

Police Killing: A case where a person dies as a result of being shot, beaten, restrained, intentionally hit by a police vehicle, pepper sprayed, tasered, or otherwise harmed by police officers, whether on-duty or off-duty.

A person was coded as Unarmed in the database if they were one or more of the following:

- not holding any objects or weapons when killed

- holding household/personal items that were not used to attack others (cellphone, video game controller, cane, etc.)

- holding a toy weapon (BB gun, pellet gun, air rifle, toy sword)

- an innocent bystander or hostage killed by a police shooting or other police use of force

- a person or motorist killed after being intentionally hit by a police car or as a result of hitting police stop sticks during a pursuit

- a driver who was killed while hitting, dragging or driving towards officers or civilians

- a driver who was driving and/or being pursued by police at high speeds, presenting a danger to the public

- people who were killed by a civilian driver or crashed without being hit directly by police during a police pursuit are not included in the database. Note that an estimated 300 people are killed in police pursuits each year and only a small proportion of these cases are included in the database (most deadly pursuits end after the driver crashes themselves into something or hits a civilian vehicle without being directly rammed/hit by police).

- were alleged to have possessed objects or weapons in circumstances other than those stated above

Polls show widespread support of Black Lives Matters protests and varied views on how to reform police | CNN Politics

About two-thirds support the recent Black Lives Matter protests over police brutality and discrimination in the US, and there's agreement on a wide variety of proposals on how to reform the nation's police departments, recent polls show.

Polls show widespread support of Black Lives Matters protests and varied views on how to reform police

https://www.cnn.com/profiles/grace-sparks

(CNN) About two-thirds support the recent Black Lives Matter protests over police brutality and discrimination in the US, and there's agreement on a wide variety of proposals on how to reform the nation's police departments, recent polls show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll out Thursday found:

64% of Americans supported the recent protests against police violence, including 86% of Democrats, 67% of independents and 36% of Republicans. Support for the protests is seen across racial lines, with 84% of blacks, 64% of Hispanics and 61% of whites in support.

A Quinnipiac University poll released Wednesday found 67% of registered voters supported the protests as a response to "the death of George Floyd at the hands of police."

The killing of George Floyd last month sparked protests nationwide over police brutality and racism against black Americans. A Pew Research poll from last week found 67% of Americans support the Black Lives Matter movement.

According to the Quinnipiac University poll, a clear majority -- 55% -- thinks the protests will lead to meaningful reform. That includes 76% of Democrats, 53% of independents and 34% of Republicans.

Widespread support exists for the protests and movement as a whole, and a majority support each proposal suggested in the Kaiser Family Foundation poll, with a few key partisan differences.

More than 9 in 10 (95%) support requiring the police to intervene and stop excessive force by other officers - and - 89% support requiring police to give verbal warning while shooting.

Another 76% support requiring states to publicly release disciplinary records for law enforcement and

74% support allowing individuals to sue police officers if they were subjected to excessive force.

Around two-thirds (68%) support banning officers from using chokeholds and strangleholds and

52% support banning no-knock warrants.

One of the deaths being protested by Black Lives Matter is that of Breonna Taylor, who was killed in her home when police officers entered without knocking and shot her while she was asleep.Majorities across party lines support every proposal, except banning no-knock warrants, with 34% of Republicans who support the proposal, 56% of independents and 65% of Democrats.

The Quinnipiac poll found a similar number in support for banning the use of chokeholds. A majority (54%) oppose cutting some funding from police departments in their community and moving it to social services compared to 41% who support shifting resources.

Voters are more favorable to police in their community than police overall in Quinnipiac's poll, with 77% who approve of how the police in their communities are doing, compared to 49% who approve of how the police overall are doing their jobs. The share of those who say they approve is down sharply from April 2018 when 65% of voters approved of the way police were doing their jobs.

One in 10 Americans say they've attended a protest against police violence or in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in the past few months, according to the Kaiser poll. The protestors are most likely to be young adults and college educated. Around half (52%) of people between 18 and 29 years old report attending a protest in the past few months, with 53% of those with a college degree who say the same.

Over half of Americans (56%) are concerned that recent protests may lead to an increase in coronavirus cases, according to Kaiser. Democrats are more likely to express concern over an increase in cases, 73% of Democrats are worried, compared to 56% of independents and 37% of Republicans.

The Kaiser Family Foundation poll was conducted June 8 through 14 among a random national sample of 1,296 adults reached on landlines or cellphones by a live interviewer. Results for the full sample have a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 3.0 percentage points.

The Quinnipiac University poll was conducted June 11 through 15 among a random national sample of 1,332 registered voters reached on landlines or cellphones by a live interviewer. Results for the full sample have a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 2.7 percentage points.

Both independents (46%) and Democrats (42%) report attending the protest in relatively high numbers, while 6% of Republicans say they have protested in support of Black Lives Matter.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez IDs 'Keys to Castle' for Real Police Reform

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez says real police and education reform will require these "keys to the castle."

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Says Protesters 'Woke' America Up

AOC gives HUGE props to folks on the front lines for the push for police reform.

Alternatives to Policing—The Case for Public Health and Community Development Investments

By Amber Yang

www.projectcensored.org

www.projectcensored.org

Alternatives to Policing—The Case for Public Health and Community Development Investments

By Amber Yang

As outrage sparks over police brutality, systemic racism, and socio-economic inequality, activists are calling to defund police. Despite other calls for anti-bias training, civilian review processes, and policies that prevent police brutality, the “Defund Police” movement sheds a light on the unprecedented expansion and intensity of policing in the last forty years. Cities spend more on policing than on health, housing, arts, parks, community development, workforce development, and civil rights combined. Instead of utilizing police as the primary tool for managing symptoms of socio-economic and race inequality, we must look at rebuilding and empowering our communities to address root causes for real change.

To understand why excessive policing can perpetuate cycles of violence, consider how governments around the world have extended “the discourse of war beyond the context of military hostilities traditionally understood.” In 1964, US President Lyndon Johnson announced a War on Poverty as he attempted to lay the foundations for a welfare state. In 1971, President Richard Nixon called drug abuse “public enemy number one” and declared a War on Drugs. In 2001, President George W. Bush declared a global War on Terror in response to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. In 2020, the War on COVID-19 framing directs our attention not to science and humanitarianism, but towards “division, fear, and security-based force.”

With billions of dollars of military hardware given to American police departments to advance their “war on crime and drugs” agenda, cities and communities have not become safer. In 2016, Baltimore had the second-deadliest year per capita on record with 318 killings. A report that same year from the US Department of Justice found that the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) engaged in massive discriminatory policing including unnecessary force, unjustified stops, and disproportionate targeting of African-Americans. In 2017, officers in the BPD’s Gun Trace Task Force were indicted on federal racketeering charges for massive abuses of power.

While some have labeled Black Lives Matter protesters as violent looters, much of the violence comes from police themselves, including agent provocateurs who instigate violence, and police tactics to suppress and defame demonstrations with rubber bullets, tear gas, and stun grenades—even with children present. Police have also targeted journalists covering the protests.

In an interview published by Truthout, sociologist Alex Vitale, coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College, said: “When our elected officials ask police to wage simultaneous wars on drugs, gangs, disorder, terror and crime, police will often be discourteous and aggressive. They will continue to violate people’s rights and use excessive and militaristic force because that is how wars are waged. It’s also built into the deep history of American policing—a tool for criminalizing people of color.”

When officers are trained to cultivate a “warrior” mindset such as above, this fuels unnecessary killings of people falsely considered a threat, such as 12-year-old Tamir Rice—killed for holding a toy gun in an Ohio park. As a former police officer shared in an article for YES! Magazine:

“When police come into every situation imagining it may be their last, they treat those they encounter with fear and hostility and attempt to control them rather than communicate with them—and are much quicker to use force at the slightest provocation or even uncertainty.”

How Do We Define “Safety”?

When we reflect on our dependence of police to provide safety, we must consider: How do we define “safety”? Whom do we feel threatened by and why?

Police in cities arrest more people for drug offenses than for other crimes, with possession—rather than manufacture or sales—accounting for the vast majority of cases. Jailing people for using drugs reinforces stigma, drives people in need of help into the shadows, and fails to address root causes, which are often associated with mental health challenges and socio-economic needs. A 2017 UN report stated that “mental health policies and services are in crisis—not a crisis of chemical imbalances, but of power imbalances,” in which “decision-making is controlled by biomedical gatekeepers whose outdated methods perpetuate stigma and discrimination.”

Instead of providing more comprehensive mental health and drug abuse services, we pour money into law enforcement, criminalize challenging behavior, and train police on how to kill fewer people in these interactions. As sociologist Alex Vitale says, people with mental illnesses are seen “not as victims of the neoliberal restructuring of public health services but as a dangerous source of disorder to be controlled through intensive and aggressive policing.” (See, for example, this story about police working with the community to help drug addicts instead of jailing them).

Community Investments Build Community Strength

We need public health interventions and strategic community investments to build community strength from the ground up. There are proven models for addressing socio-economic problems without relying primarily on police:

- The Oakland Power Projects aims to “reject police and policing as the default response to harm and to highlight or create alternatives that actually work by identifying current harms, amplifying existing resources, and developing new practices that do not rely on policing solutions.” In the Project’s “Know Your Options” workshops, community street medics and health care workers of all backgrounds build skills and knowledge around preventative care, emergency skills, and mental health and de-escalation tactics.

- Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) is a mobile crisis intervention service in Eugene, Oregon that shares a central dispatch with the Eugene Police Department (EPD) and is funded by the City of Eugene’s public safety services. Every day from 11am and 3am, the CAHOOTS van provides free first-response services—including non-emergency medical care, basic first aid, mental crisis intervention, counseling, mediation, transportation, case assessment, referral and advocacy. CAHOOTS workers estimate that they save EPD over $4.5 million annually and save more than $1 million more in medical expenses.

- Restorative justice is a harm-reduction approach that developed out of indigenous peacemaking practices and is proven to be highly effective in school settings. It uses cooperative processes to hold people who have done harm accountable and to support them in the transformation of their own behavior—often with the direct involvement of people whom harm was done to. Turning school discipline over to police invariably results in more suspensions, expulsions, and arrests directed at high-needs youth. Real alternatives are restorative justice programs that involve meaningful community service, trauma-informed wellness strategies, and conflict resolution circles. Along with that, we need more counselors, social workers, and afterschool programs. Restorative Response Baltimore helps youth get to the roots of conflicts that might otherwise escalate to violence. Using structured dialogue, communities resolve their problems without the threat of violence and incarceration. Safe Streets Baltimore is utilizing “credible messenger” strategies—adults from the community with a history of street involvement help address neighborhood violence by providing trauma counseling and street mediation, and by steering youth into pro-social activities.

- The 414LIFE is a similar effort that uses the “Cure Violence”model to take a public health approach to gun violence. This strategy has been used in 25 cities and was the subject of an acclaimed documentary. “Violence functions like the flu. From the public health standpoint, you want to inoculate somebody to prevent the spread,” said 414LIFE member and trauma psychologist Terri deRoon-Cassini.

Justice Reinvestment

“A reform that begins with the officer on the beat is a continuance of the preference for considering actions of ‘bad’ individuals, as opposed to functions and intentions of a system,” Vitale asserted. A growing number of local activists in Minneapolis like Reclaim the Block, Black Visions Collective and MPD 150 are demanding Mayor Jacob Frey to defund the police by $45m and shift those resources into “community-led health and safety strategies.” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti just announced that the city would identify $250 million in cuts in its police department, which has an annual budget of $1.6 billion.

Following these efforts, cities could establish those funds to provide employment, invest in affordable housing and schools, and increase access to social services that help people get their basic needs met. Investing in community land trusts and cooperatives also help create housing equity by decentralizing housing development and ownership. In 2019, 117 rights groups released Vision for Justice: 2020 and Beyond—an expanded, holistic framework to transform the US criminal-legal system by prioritizing “upfront investments in noncarceral programs and social services.” Funds could also go to clean air and water, green spaces, walkable neighborhoods, lively public spaces, vital social institutions, and other avenues for public engagement—basic ingredients for belonging and well-being.

Vitale expressed another way to reinvest funds in an interview published by The Intercept: “We know there are neighborhoods where problematic behavior is highly concentrated, and local and state officials spend millions of dollars to police and incarcerate people. What if those communities kept some percentage of people who get arrested in the community and tried to develop strategies for resolving their problems, and in return, the community got the money that would have been spent incarcerating them?”

Empowering and resourcing our communities to resolve situations and conflicts on their own help repair the social fabric frayed by division, diminished human and civil rights, and centralization of power—with minimal or no police intervention. As Vitale eloquently states, the very nature of policing and the law is to “be a tool for managing inequality and maintaining the status quo.” We need real alternatives to systemically address the root causes and solutions of violence and inequality, while also actively working to build a shared narrative of collaboration, community empowerment, mutual compassion, and human goodness.

The NYPD Files: Search Thousands of Civilian Complaints Against New York City Police Officers - ProPublica

After New York state repealed a law that kept NYPD disciplinary records secret, ProPublica obtained data from the civilian board that investigates complaints about police behavior. Use this database to search thousands of allegations.

projects.propublica.org

The NYPD Files

Search Thousands of Civilian Complaints Against New York City Police Officers

by Derek Willis, Eric Umansky and Moiz Syed, July 26, 2020.

After New York state repealed a law that kept police disciplinary records secret, ProPublica sought records from the civilian board that investigates complaints by the public about New York City police officers. The board provided us with the closed cases of every active-duty police officer who had at least one substantiated allegation against them. The records span decades, from September 1985 to January 2020. We have created a database of complaints that can be searched by name or browsed by precinct or nature of the allegations. Read more about this data → | Related: We’re Publishing Thousands of Police Discipline Records That New York Kept Secret for Decades →

Albuquerque Police Engaged in Secret Intelligence Gathering Operation, Leaked Documents Show

Leaked documents reveal that the Albuquerque Police Department (APD) has engaged in a large-scale data and intelligence gathering operation since 2006 carried out entirely by private citizens and corporate partners.

www.counterpunch.org

www.counterpunch.org

Albuquerque Police Engaged in Secret Intelligence Gathering Operation, Leaked Documents Show

Leaked documents reveal that the Albuquerque Police Department (APD) has engaged in a large-scale data and intelligence gathering operation since 2006 carried out entirely by private citizens and corporate partners. This privatization of data-gathering means APD has avoided community oversight and judicial review in the acquisition of this information, some of which would have required a warrant to collect. In addition, documents show this operation has been used on at least two occasions for explicitly partisan political purposes.

The documents were part of a June 19, 2020—Juneteenth—leak of police data by a group called Distributed Denial of Secrets (DDOS). Referred to as “BlueLeaks,” the leak included 269 gigabytes of information from more than 250 police departments that DDOS said it had received from the hacking group Anonymous. According to DDOS, Anonymous hacked into the servers of a private web hosting and software company called Netsential, a vendor of web-based software for hundreds of clients, including many local and regional police departments. Netsential confirmed its servers were compromised. And the National Fusion Center Association, the group that represents the state-run federal data centers at the center of the leak, confirmed the documents are real.

The Albuquerque Police Department hired Netsential years ago, with money from the Target corporation, to build a secure website called CONNECT. The City of Albuquerque calls the “Community Oriented Notification Network Enforcement Communication Technology or CONNECT… an interactive tool which links law enforcement to community partners to communicate about crime and public safety issues occurring in Albuquerque.” The DDOS release included APD documents related to CONNECT, which included reports, emails, membership rosters, and more.

Netsential built CONNECT so that APD could merge data gathering among its various anti-crime programs, which include retail, property and anti-gang units. One of these anti-crime programs, the Albuquerque Retail Assets Protection Association (ARAPA), is a previously little known “public-private partnership” between the Albuquerque police department and big box retailers such as Walmart and Target that began in 2006. APD officials have said little publicly about the program, but when APD officials have spoken on record, they have described it as relatively small in scale—a few hundred retailers— and focused on retail and property crime. But according to the recently leaked documents, ARAPA and its successor CONNECT are much larger than APD has claimed, and the focus of the data and information gathering operation includes much more than retail and property crime.

Private security forces, along with APD employees, have recruited retailers to join ARAPA since its inception. Once approved to the program, APD gives those members access to a secure website where they can upload videos, images, descriptions, or other information related to possible retail or property crime. But APD and its corporate partners place no limits on the information or data that retailers can upload, other than reminding members by email that “all subjects are innocent until proven guilty,” and also that “as a participant in this program it is your responsibility to protect the confidentiality of any material distributed.”

Uploaded information is immediately available to all ARAPA members, including a team of five APD investigators assigned to investigate ARAPA tips, according to APD. ARAPA and CONNECT information has been stored on APD servers, managed by Netsential, in a searchable database. Police officials have claimed that only a small team of APD investigators assigned to ARAPA access the information, along with a handful of other local law enforcement agencies. APD says this list is limited to the local sheriff, US postal inspectors, and the District Attorney.

The BlueLeaks documents paint a different picture. ARAPA, according to BlueLeaks documents, has grown from its modest beginnings in 2006 into a significant private-sector intelligence and data-gathering operation conducted on behalf of police. Big Box retailers upload photos, video, descriptions, license plate numbers, and more to a database owned by APD. Leaked files reveal a membership roster that includes thousands of Albuquerque residents, business organizations, neighborhood association block captains, apartment managers, hotel clerks, bank tellers, pawnshop owners, and more who have been, or currently are, engaged in information gathering for APD. And internal emails show that the operation was not solely about the investigation of alleged retail or property crimes but focused also on general data and intelligence gathering. APD encouraged ARAPA members to upload any information they had to CONNECT, including information on any activity that members deemed “suspicious.”

Albuquerque police have said little publicly about the program, but in 2010 APD officials told the Police Executive Research Forum, a police industry consulting firm, that ARAPA and CONNECT included a few hundred retailers and a handful of police from a small group of local police agencies. Officials told the Albuquerque Journal in a 2013 story that only a small team of APD investigators used the data. But the BlueLeaks documents show CONNECT has included 2,666 users across more than a dozen different data gathering operations. Nearly a third of all the names on the list are local, state, or federal law enforcement officers. Most with access to the information are or have been affiliated with APD, or the local sheriff’s office, but the list includes hundreds of officers from departments, including federal agencies, with no clear role in retail crime enforcement in Albuquerque.

The documents demonstrate that APD has not only privatized information and intelligence gathering but has also shifted the authority to determine policing priorities to the private sector. Since its inception, a vast majority of ARAPA or CONNECT representatives with the authority to approve business and law enforcement access requests have been private sector or non-police employees of APD. One of the founders of ARAPA, Karen Fischer, worked at APD as its Strategic Support Division Manager until her retirement in 2012. Another was a Target employee named Craig Davis, who now works in private security. Between the two of them, they recruited and approved hundreds of retailers, hotel clerks, apartment managers, and bank tellers, among others, to gather information for APD. In addition, they and other corporate agents vetted requests by law enforcement officers for access to the data, approving requests from agents who do not work on retail and property crime enforcement. These included a special agent for the US Forest Service, an intelligence coordinator and also an agent from the Drug Enforcement Agency’s New Mexico High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, multiple special agents from the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an intelligence research specialist from DHS Homeland Securities Investigations, a DHS Customs and Border Patrol agent, and a DHS agent in Intelligence and Analysis. They gave access to police officers from departments in eight states, police officers from the Albuquerque Public Schools and the University of New Mexico, a Bureau of Indian Affairs special agent, and a detective and two investigators with the 377 Security Forces Squadron from Kirtland Air Force Base.

Among those who Fischer or Davis recruited to collect data, most worked in the local retail or hospitality industry, but they also recruited or approved members with access to information unrelated to retail or property crime. And many of those members had access to information that would have required a warrant for APD to collect it. In 2008, APD approved membership to a woman named Anita Alatorre, the office manager at Metamorphosis of NM, a substance abuse treatment clinic in Albuquerque. In an internal message regarding Alatorre’s membership, Fischer wrote that she “Sent note to M. Conrad on 4-11-08 regarding approval. IS drug treatment program appropriat? [sic] Approved via e-mail by m. Conrad on 4-14-08.” M. Conrad is likely a reference to then Southeast Area Commander Murray Conrad, who is referenced elsewhere in the documents as Com. Conrad.

The documents also show that ARAPA has been used for political purposes. Fischer vetted, and Conrad approved, Erin Muffoletto, a business and political lobbyist from Muffoletto Consulting, LLC. No concerns appear to have been raised by either Fischer or Conrad about giving the owner of a “Business and Government Relations lobbying and consulting business,” as ARAPA characterized her, access to a law enforcement database. In addition, the documents include a February 2011 email from ARAPA to its private-sector members encouraging them to lobby the state legislature on behalf of a bill favored by the Albuquerque Police Department.

“Greetings ARAPA Partners! As many of you know, SB 223 is currently heading through the Judiciary Committee and will be heard this coming Monday, Feb 28th at 2:00pm at the Roundhouse in Santa Fe. We have received information that there will be a large presence of Trial Lawyer’s [sic] present to denounce this bill. IT IS IMPARATIVE [sic] that we have a Strong Showing from the Retail Loss Prevention / Retail Store Leadership present for the hearing in support of the bill. I’m asking that as many members of ARAPA that can show up, please be there. Let me stress that you do not have to Speak, just be there to raise your hand in support of this bill. I hope we can count on each of you to be present. The two bills going through are critical in our next steps to stem the tide of Organized Retail Crime in our City and the State of New Mexico! If you have any questions, please contact Ken Cox, Craig Davis or Karen Fischer.”

Fischer still worked at APD at the time she sent the email. And it’s not the only time an APD employee used ARAPA for political purposes. In a March 20111 email, Fischer forwarded a message to ARAPA members from Jimmie Glenn, then the President of the NM Retail Association, in which he referred to then Democratic Majority Leader Michael Sanchez as “our toughest obstacle.”

Fischer and others did not just control who gathered the data, they vetted and approved which law enforcement officers had access to the data and this pattern continues. In January of this year, Steven Roberts, an ARAPA member and a security division executive with Smith’s grocery stores, approved data access to a Homeland Security Specialist with the New Mexico Department of Homeland Security. Fischer, Davis, and Roberts, and other private industry representatives, have approved access to UNM and CNM students, two UNM professors, a past president of UNM’s Student and Family Housing Residents Association, religious leaders from Trinity United Methodist and Monte Vista Christian Churches, and the manager of systems support at the Albuquerque airport terminal RADAR. Private-sector ARAPA leaders encouraged neighborhood associations to join, suggesting that block captains persuade homeowners to link residential doorbell and security cameras to APD via CONNECT.

There is nothing particularly unique about public-private information gathering partnerships. Nearly every police agency, local or federal, relies on information collected from corporate or private security firms. Some police rely on information purchased from data aggregating companies such as ChoicePoint, which maintains enormous databases of information that it tailors for clients, including law enforcement. The Department of Homeland Security has developed a network of “fusion centers”—including one in Santa Fe—that serve as a public sector version of this data aggregation. But the BlueLeaks documents show the extent to which APD pursued its own, largely secret, and fully privatized, information gathering operation, merging multiple different data gathering operations.

The privatization of data and information gathering, and the private sector control of intelligence collected for police, raises troubling implications for a department already under intense scrutiny. In 2014, the Department of Justice concluded that APD had demonstrated a long-standing “pattern and practice of unconstitutional policing.” Since 2015, and following the federal investigation, APD has operated under a federal court-ordered settlement agreement that has imposed significant reforms on APD. Among the deficiencies identified by the Department of Justice in its 2014 report were “inadequate accountability standards.” In addition, the DOJ noted a pattern of “insufficient oversight” within APD and “external oversight” that DOJ concluded was “broken and has allowed the department to remain unaccountable to the communities it serves.” The BlueLeaks information, and previous reporting about Albuquerque police by AbolishAPD, shows that these issues run much deeper than what the DOJ revealed in its investigation.

An intent to avoid community oversight and judicial review may explain ARAPA’s unusual organizational structure. ARAPA registered with the New Mexico Secretary of State as a private, non-profit corporation in August 2012. The incorporation papers listed Fischer and Davis as among its three-person board of directors. Fischer retired from APD on Jan. 1, 2013. On the day prior to Fischer’s retirement, former APD chief Ray Schultz signed a $26,400 contract with ARAPA to manage APD’s data gathering operation. The contract between the City and ARAPA listed the ARAPA address as a post office box, which would establish it as an entity independent of APD, but in separate incorporation papers that Fischer and Davis filed with the state of New Mexico, they listed its address as 400 Roma Ave NW, Albuquerque, the same address as the Albuquerque police department.

Legal observers and Constitutional scholars point to a number of potential legal implications raised by public-private partnerships in policing. These include concerns over privacy and the lack of oversight and judicial review of policing activities when undertaken by the private sector on behalf of public police agencies, but also extend to worries that the privatization of information gathering by police might result in the privatization of public law enforcement priorities and practices. Do corporate retail interests, at least in part, determine police priorities in Albuquerque? The BlueLeaks documents suggest this may be the case.

The Target Corporation gave APD $100,000 for the creation of CONNECT. Its executives, along with executives from Walmart, have served in leadership positions at ARAPA and CONNECT from the beginning, and continue to do so. Executives from the two corporations determine who gets to join ARAPA, who collects information for APD via CONNECT, and which law enforcement agencies get access to the information. Though Walmart and Target are just two of thousands of retailers who have been involved with CONNECT since its inception, an overwhelming percentage of APD’s retail policing in Albuquerque takes place at these two retailers. We reviewed all misdemeanor shoplifting citations issued, and arrests made, by APD during the month of January 2020. Nearly 60 percent of all shoplifting criminal complaints filed with the court by APD came from Walmart or Target.

The City of Albuquerque recently announced its intent to petition the federal court to release APD from portions of its court-approved settlement agreement. The City’s Mayor, Tim Keller, claims the department has implemented new accountability measures and have established new and robust internal and external oversight mechanisms. He recently proposed increasing the police budget and has long promised to hire hundreds of additional police officers. But the BlueLeaks documents show that Keller proposes giving more money and more cops to a police department that has spent years implementing a data and intelligence gathering operation that it has used for political purposes, that it has designed to avoid oversight and accountability, and that it relies on to provide it and federal agents access to information without judicial review.

An Alternative to Police That Police Can Get Behind

In Eugene, Oregon, a successful crisis-response program has reduced the footprint of law enforcement—and maybe even the likelihood of police violence.

Should american cities defund their police departments?

The question has been asked continually—with varying degrees of hope, fear, anger, confusion, and cynicism—since the killing of George Floyd on Memorial Day. It hung over the November election: on the right, as a caricature in attack ads (call 911, get a recording) and on the left as a litmus test separating the incrementalists from the abolitionists. “Defund the police” has sparked polarized debate, in part, because it conveys just one half of an equation, describing what is to be taken away, not what might replace it. Earlier this month, former President Barack Obama called it a “snappy slogan” that risks alienating more people than it will win over to the cause of criminal-justice reform.

Yet the defund idea cannot simply be dismissed. Its backers argue that armed agents of the state are called upon to address too many of society’s problems—problems that can’t be solved at the end of a service weapon. And continued cases of police violence in response to calls for help have provided regular reminders of what can go wrong as a result.

Annie Lowrey: Defund the police

In September, for example, new details came to light about the death of a man in Rochester, New York, which police officials had initially described as a drug overdose. Two months before Floyd’s death, Joe Prude had called 911 because his brother Daniel was acting erratically. Body-cam footage obtained by the family’s attorney revealed that the officers who responded to the call placed a mesh hood over Daniel’s head and held him to the ground until he stopped moving. He died a week later from “complications of asphyxia in the setting of physical restraint,” according to the medical examiner. Joe Prude had called 911 to help his brother in the midst of a mental-health crisis. “I didn’t call them to come help my brother die,” he has said.

A few weeks after a video showing Daniel Prude’s asphyxiation was made public, police in Salt Lake City posted body-cam footage that captured the moments before the shooting of a 13-year-old autistic boy. The boy’s mother had called 911 seeking help getting him to the hospital. While she waited outside, a trio of officers prepared to approach the home. One of them hesitated. “If it’s a psych problem and [the mother] is out of the house, I don’t see why we should even approach, in my opinion,” she said. “I’m not about to get in a shooting because [the boy] is upset.” Despite these misgivings, the officers pursued the distressed 13-year-old into an alley and shot him multiple times, leavinghim, his family has said, with injuries to his intestines, bladder, shoulder, and both ankles.

Neither these catastrophic outcomes nor the misgivings of police themselves have produced an answer to the obvious question: How should society handle these kinds of incidents? If not law enforcement, who should intervene?

Left: A sign displays the number to dial for CAHOOTS. Right: Dennis Ekanger, a co-founder of the White Bird Clinic.

One possible answer comes from Eugene, Oregon, a leafy college town of 172,000 that feels half that size. For more than 30 years, Eugene has been home to Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets, or CAHOOTS, an initiative designed to help the city’s most vulnerable citizens in ways the police cannot. In Eugene, if you dial 911 because your brother or son is having a mental-health or drug-related episode, the call is likely to get a response from CAHOOTS, whose staff of unarmed outreach workers and medics is trained in crisis intervention and de-escalation. Operated by a community health clinic and funded through the police department, CAHOOTS accounts for just 2 percent of the department’s $66 million annual budget.

When I visited Eugene one week this summer, city-council members in Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Houston, and Durham, North Carolina, had recently held CAHOOTS up as a model for how to shift the work of emergency response from police to a different kind of public servant. CAHOOTS had 310 outstanding requests for information from communities around the country.

Read: Why Minneapolis was the breaking point

A pilot program modeled in part on CAHOOTS recently began in San Francisco, and others will start soon in Oakland, California, and Portland, Oregon. Even the federal government has expressed interest. In August, Oregon’s senior senator, Ron Wyden, introduced the CAHOOTS Act, which would offer Medicaid funds for programs that send unarmed first responders to intervene in addiction and behavioral-health crises. “It’s long past time to reimagine policing in ways that reduce violence and structural racism,” he said, calling CAHOOTS a “proven model” to do just that. A police-funded program that costs $1 out of every $50 Eugene spends on cops hardly qualifies as defunding the police. But it may be the closest thing the United States has to an example of whom you might call instead.

Andrew Ferguson: ‘Defund the police’ does not mean defund the police. Unless it does.

A pile of belongings on the sidewalk in a Eugene neighborhood bears a note: “I’m going to White Bird.” The White Bird Clinic runs the CAHOOTS crisis-response program.

in 1968, Dennis Ekanger was a University of Oregon graduate student finishing up an internship as a counselor for families with children facing charges in the state’s juvenile-justice system when he started to get calls in the middle of the night.

Through his work in court, word had spread that “I knew something about substance-abuse problems,” Ekanger told me recently. Anxious mothers were arriving at his doorstep desperate for help but afraid to go to the authorities. It was a turbulent time in Eugene, with anti-war protests on the University of Oregon campus and a counterculture that spilled over into the surrounding neighborhoods in the form of tie-dye, pot smoke, and psychedelic drugs.

The following year, Ekanger and another student in the university’s counseling-psychology program, Frank Lemons, met with a prominent Eugene doctor who agreed to help them mount a more organized response by recruiting local health-care providers to volunteer their time. Ekanger went to San Francisco to visit a new community health clinic in Haight-Ashbury that had pioneered such a model, offering free medical treatment to anyone who walked in. Back in Oregon, Ekanger and Lemons each put up $250 and signed a lease on a dilapidated two-story Victorian near downtown.

The White Bird Clinic opened its doors a few days later, with a mission to provide free treatment when possible and to connect patients to existing services when it wasn’t. But the city’s established institutions didn’t yet have a clue how to deal with people on psychedelic drugs. Teenagers who showed up in the emergency room on LSD were prescribed antipsychotic medications. Unruly patients got passed to the police and ended up having their bad trips in jail.

The forerunner to CAHOOTS was an ad hoc mobile crisis-response team called the “bummer squad” (for “bum trip”), formed in White Bird’s first year for callers to the clinic’s crisis line who were unable or unwilling to come in. The bummer squad responded in pairs in whatever vehicle was available. For a while, that was a 1950 Ford Sunbeam bread truck that did double duty as the home of its owner, Tod Schneider, who’d dropped out of college on the East Coast to drive out to Eugene.

It didn’t take long for the bummer squad to start showing up at some of the same incidents that drew a response from Eugene police. One day in the late 1970s, Schneider answered a call from a mother concerned about her son. “Mom, I think I made a mistake,” he’d told her. “I took some PCP, and I’m feeling weird.” Schneider showed up to the family’s home to find the teenager in “full psychotic PCP condition.” As Schneider got out of the truck, the boy came running out of a neighboring house naked and bloody, and tackled him. Another neighbor called the police, thinking they were witnessing an assault. “So police came out and figured out what was going on—they talked to me a little bit, and they just left,” Schneider told me. “The police realized … they didn’t know what to do with these people that was productive.”

White Bird continued its volunteer-run mobile crisis service—and its informal collaboration with the police—into the early 1980s. Bummer-squad volunteers periodically gave role-playing training to the police department, and some beat officers grew to appreciate Eugene’s peculiar grassroots crisis-response network.

In the late ’80s, Eugene was struggling to respond to a trio of convergent issues that still plague the city more than 30 years later: mental illness, homelessness, and substance abuse. Police in Eugene were caught in a cycle of arresting the same people over and over for violations such as drinking in public parks and sleeping where they weren’t allowed to.

“The police hated it; we were doing absolutely nothing for public safety, we were tangling up the courts, and we were spending a horrendous amount of money,” Mike Gleason, who was the city manager at the time, recalled. Gleason convened a roundtable with Eugene’s social-service providers, offering city funding for programs that could break the logjam. A local detox facility made plans to launch a sobering center where people could dry out or sleep it off. White Bird and the police department began a dialogue about a mobile crisis service that could be dispatched through the 911 system.

White Bird and the police were not a natural pairing. To the city’s establishment types, White Bird staffers were “extreme counterculture people.” Standing by as the bummer squad defused a bad trip was one thing; giving the team police radios was quite another. White Bird’s clinic coordinator at the time, Bob Dritz, wore a uniform of jeans and a T-shirt; for meetings with city officials, he’d occasionally add a rumpled corduroy jacket. With his defiantly disheveled appearance, Dritz seemed to be declaring, in the words of one colleague, “Look, I’m different from you people, and you have to listen to me.” White Bird staff members worried that working with the police would erode their credibility, and maybe even lead to arrests of the very people they were trying to help. But in the space of a couple of months, Dritz and a counterpart at the police department drafted the outlines of a partnership. The acronym Dritz landed on was an ironic nod to the discomfort of working openly with the cops.

Things were slow at first. Jim Hill, the police lieutenant who oversaw CAHOOTS at the police department, recalls sitting at his desk listening to dispatch traffic on the radio. “I would literally have to call dispatch and say, ‘How come you didn’t send CAHOOTS to that?’ And they go, ‘Oh, yeah, okay.’” Before long, though, CAHOOTS was in high demand.

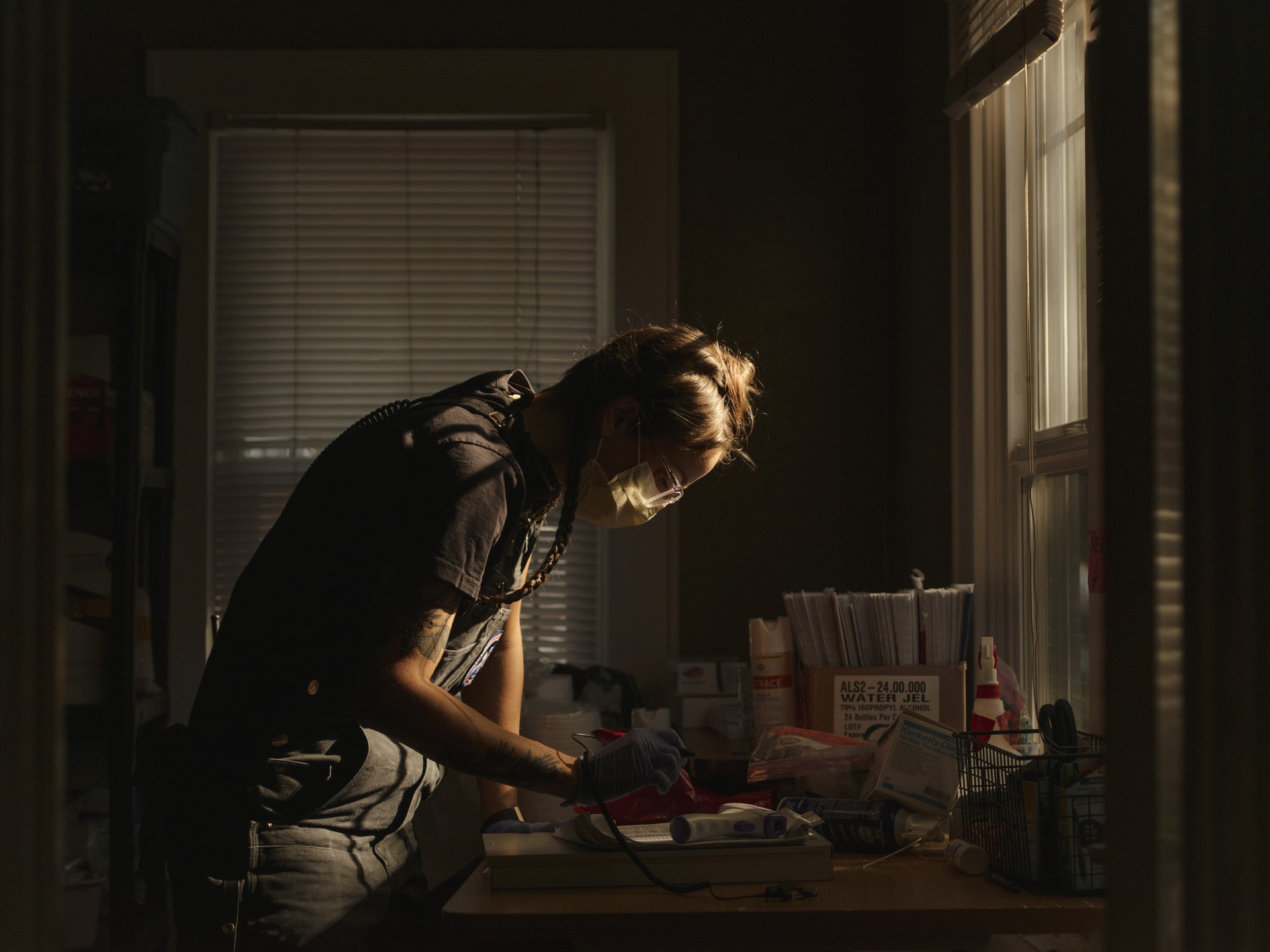

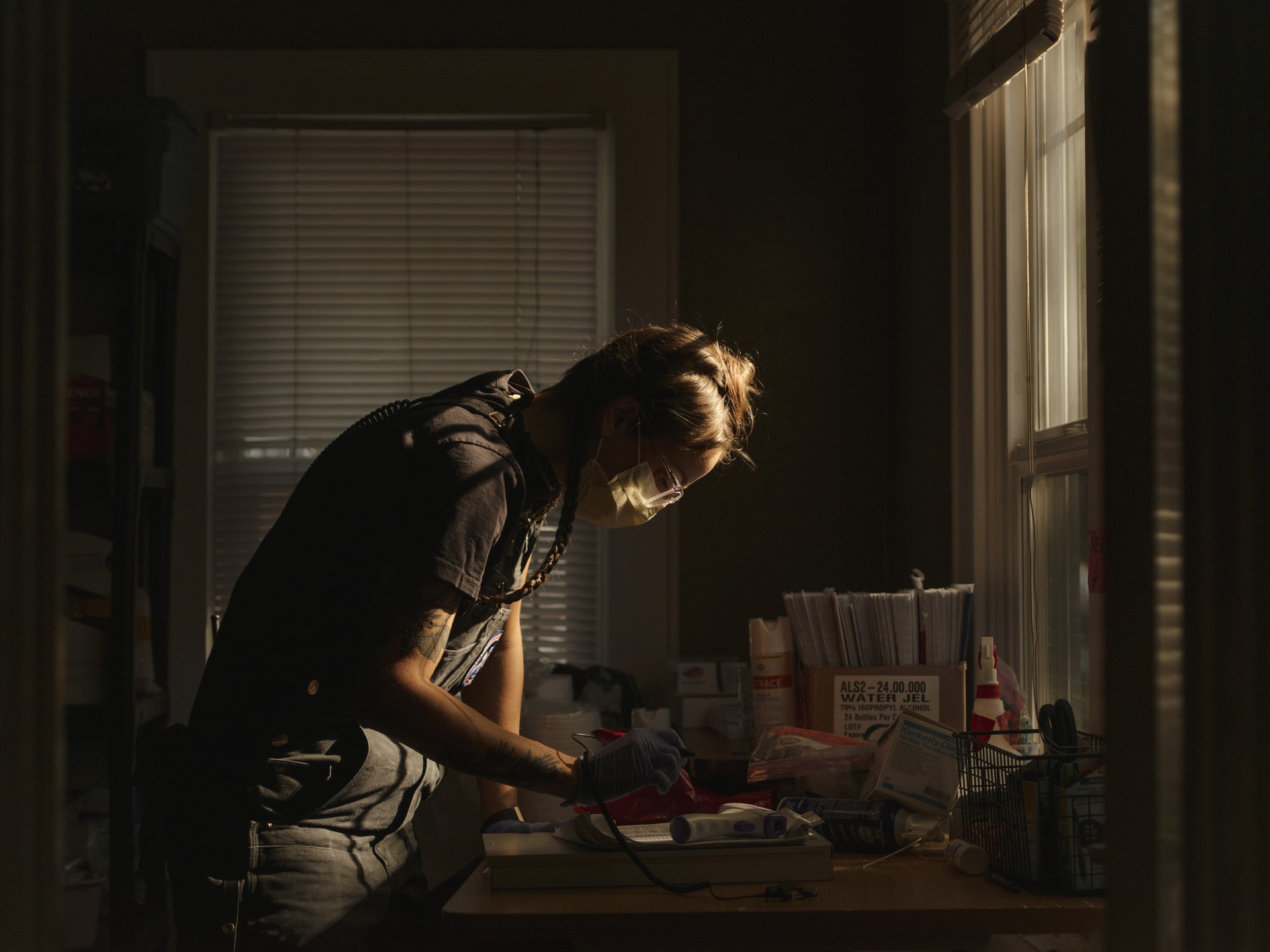

Chelsea Swift and Simone Tessler talk with a person who needs a place to stay.

cahoots teams work in 12-hour shifts, mostly responding without the police. Each van is staffed by a medic (usually an EMT or a nurse) and a crisis worker, typically someone with a background in mental-health support or street outreach, who takes the lead in conversation and de-escalation. Most people at White Bird make $18 an hour (it’s a “nonhierarchical” organization; internal decisions are made by consensus), and some have day jobs elsewhere.

One Tuesday night this summer, the medic driving the van was Chelsea Swift. Swift grew up in Connecticut and, like White Bird’s co-founder a generation before her, was introduced to harm-reduction work in Haight-Ashbury, where she sold Doc Martens to the punks who staffed the neighborhood needle-exchange program. Swift’s childhood had been marked by her mother’s struggle with opiate addiction and mental illness. She never thought she’d be a first responder, or could be. She was too queer, too radical. “I don’t fit into that culture,” she told me. And yet, she said, “I am so good at this job I never would have wanted.”

Around 6 p.m., Swift and her partner, a crisis worker named Simone Tessler, drove to assist an officer responding to a disorderly-subject call in the Whiteaker, a central-Eugene neighborhood with a lively street life, even in pandemic times. When we arrived, a military veteran in his 20s was standing with the officer on the corner, wearing a backpack, a toothbrush tucked behind his ear. The man said he’d worked in restaurants in Seattle until the coronavirus hit, then moved to Eugene to stay with his girlfriend.

That day, he’d worked his first shift at a fast-food restaurant. Soon after he got home, a sheriff’s deputy working for the county court knocked on the door to serve him a restraining order stemming from an earlier dispute with his girlfriend. He did not take the news well. The deputy called for police backup, and when it arrived, the man agreed to walk a block away to wait for CAHOOTS and figure out his next move. He had to stay 200 feet away from the place where he’d been living, and he couldn’t drive. “I been drinking a bit, and—I’m not gonna lie—I want to keep drinking,” he said. He needed somewhere to stay, and a way to move his car to a place where he could safely leave it overnight with his stuff in the back.

Swift and the officer talked logistics while Tessler leaned against the wall beside the man and chatted with him. She told him that she’d worked in restaurants before joining CAHOOTS.

The Eugene Mission, the city’s largest homeless shelter, had an available spot, the officer explained, thumbs tucked inside the shoulder straps of his duty vest. You can show up drunk if you commit to staying for 14 days and agree not to use alcohol or drugs while you’re there.

The man hesitated, thinking through other options. He had enough cash for a motel room, as long as it didn’t require a big deposit. The officer prepared to leave so CAHOOTS could take over. Swift, Tessler, and the veteran took out their phones and began looking up budget motels along a nearby strip, settling on one with a military discount and a low cash deposit.

“Do you know how to drive stick?” the man asked. Tessler and Swift exchanged blank looks, then continued to spitball. Did the man have AAA? Was another CAHOOTS unit free to help? I felt a lump rising in my throat. I’d wanted to keep my reporterly distance, but I was also a person watching a trivial problem stand in the way as calls stacked up at the dispatch center. I drove the car three blocks to the motel with Swift in the front seat.

“So much of what people call CAHOOTS for is just ordinary favors,” she said. “We’re professional people who do this every day, but what was that? We were helping him make phone calls and move his car.”

A couple of hours later, CAHOOTS received a call from a sprawling apartment complex on the north side of town. Tessler and Swift showed up just as the last hint of blue drained from the sky. The call had come from a concerned mother who lived in Portland, 100 miles away from her 23-year-old daughter; she believed that her daughter was suicidal. The young woman’s grandmother, who lived nearby, stood in the parking lot and gave Tessler and Swift a synopsis: Her granddaughter was bipolar, with borderline personality disorder. She’d run away at 17 after her diagnosis, and never seemed to fully accept it, traveling across the West with a series of boyfriends, sleeping in encampments. She’d been back in Eugene for a few months now, the longest the family had ever gotten her to stay.

Tessler walked around the corner and knocked. “It’s CAHOOTS.” No answer.

“Can you come and talk to us for a minute?”

The door was unlocked from the inside and left slightly ajar.

The apartment was dark. A tiny Chihuahua mix barked frantically. A tearful voice called out from the bedroom, “I just want a hug. Are you going to take me away?”

Tessler crouched down in the bedroom doorway. “I’m not gonna take you anywhere you don’t want to go.”

“I’m really sorry I’ve caused all this,” the young woman said, sitting up.

Swift grabbed a handful of kibble from a bowl on the floor to quiet the dog. “My family tries to put me away a lot,” the young woman explained. Breathing fast between sobs, she seemed both overwhelmed by grief and adrenaline and primed to answer questions she’d come to expect in the midst of a crisis.

Unprompted, she told the CAHOOTS team her full name, letter by letter. “I know my Social Security number, and I know I’m a harm to myself and others.” She took a deep breath. “I’m just feeling really sad and alone, and I don’t know how I got here.”

Tessler turned on a light, and Swift went out to the parking lot to summon the young woman’s grandmother.

“Nana! Nana!” The young woman dissolved into her embrace.

Swift surveyed the bathroom scene that had prompted the call. An open pack of cigarettes lay on the wet floor along with a belt and an electrical cord. There was a straw in a bottle of gin on the edge of the tub, a six-pack on the toilet, and half a dozen pill bottles strewn across the bathroom sink and countertop. Swift unfolded a soggy piece of paper marked “Patient Safety Plan Contract” that identified seeing San Francisco as the one thing the young woman wanted to do before she died.

As Swift took her vitals, the young woman’s tearful reunion with her grandmother continued. “I love your blue eyes, Nana,” she said.

“I love your brown ones.”

CAHOOTS brought her to the emergency room, and she was discharged less than 24 hours later.

Left: A CAHOOTS van. Right: A CAHOOTS caller receives treatment.

on my first morning in eugene, I spent a couple of hours in Scobert Gardens, a pocket-size park on a residential block not far from the Mission. Many of the park’s visitors are part of Eugene’s unhoused population, which accounts for about 60 percent of CAHOOTS calls. Everyone I met in Scobert Gardens had a CAHOOTS story. One man had woken up shivering on the grass before dawn, after the park’s sprinklers had soaked him through; CAHOOTS gave him dry clothes and a ride to the hospital to make sure he didn’t have hypothermia. A woman had received first aid after getting a spider bite on her face while sleeping on the ground. Another man hadn’t had a place to stay since he got out of prison more than a year ago. When he had a stroke in the park earlier this summer, a friend called CAHOOTS. “If you go with the ambulance, it will cost you big money, so a lot of people go the CAHOOTS route,” the man explained.

Earlier this year, Barry Friedman, a law professor at NYU, posted a working paper on policing that highlighted the mismatch between police training and the jobs officers are called on to do—not just law enforcer, but first responder, mediator, and social worker. Reducing the number of instances in which police are called to assist Eugene’s unhoused population reduces the number of calls for which their skill set is a poor match. But if the goal is eliminating unnecessary use of force, helping people without housing is hardly sufficient.

In a 2015 analysis of citizen-police interactions, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that traffic stops accounted for the majority of police-initiated contact: 25 million people reported traffic stops, versus 5.5 million people who reported other kinds of contact. And police are regularly involved in incidents that escalate partly because of a failure to consider mental-health issues. In October, Walter Wallace Jr.’s family members and a neighbor called 911 because he was arguing with his parents; according to the family’s attorney, Wallace had bipolar disorder. Two Philadelphia police officers arrived, found Wallace with a knife, and fatally shot him, despite his mother’s attempts to intercede. (Police and district-attorney investigations are ongoing, and no arrests have been made.) Near Eugene, police in the neighboring city of Springfield in March 2019 killed Stacy Kenny, who had schizophrenia, in an incident that began with a possible parking violation. None of the officers involved was criminally charged, though a lawsuit brought by the Kenny family resulted in the largest police settlement in Oregon history. Springfield also committed to overhauling police-department policy and oversight practices around use of force.

Read: What the world could teach America about policing

In July 2015, police responded to the home of Ayisha Elliott, a race and equity trainer and the host of a podcast called Black Girl From Eugene. Elliott’s 19-year-old son had been experiencing a mental-health crisis, she told me, which was the result of a traumatic brain injury. At 2:43 a.m., Elliott called Eugene’s nonemergency number and asked for CAHOOTS, not realizing that the service ran only until 3 a.m. In a subsequent call, to 911, Elliott’s ex-husband indicated that Elliott was in danger; authorities say it was this second call that led dispatchers to send police to the scene. Elliott greeted the officers on the front porch, and explained that she needed help getting her son to the hospital. Instead, in an incident that escalated over the course of 15 minutes, her son became agitated and began to yell. Elliott attempted to shield him from officers as they ordered her to stand back. Police say her son charged as they tried to separate him from his mother. Her son was punched in the face and tased. Elliott herself was pulled to the ground, resulting in a concussion, she said. She was arrested for interfering with a police officer. (She was released the following morning.) She and her son sued the city of Eugene as well as individual police officers in federal court, for excessive use of force and racial discrimination, among other claims; the court found against the plaintiffs on all counts. Elliott told me the experience didn’t change her view of the police so much as confirm it. “I realized that it didn’t matter who I was; I’m still Black.”

ogether with the fatal police shooting that year of a veteran who had PTSD, the incident helped focus public attention on Eugene’s response to mental-health crises. In its next annual budget, the city included $225,000 to make CAHOOTS a 24/7 service for the first time. (Both the mayor’s office and the police department say the increase in funding was not related to a specific incident.)

Yet CAHOOTS is still limited by the rules that govern its role in crisis response. Its teams are not permitted to respond when there’s “any indication of violence or weapons,” or to handle calls involving “a crime, a potentially hostile person, a potentially dangerous situation … or an emergency medical problem.”

Many 911 calls unfold in the gray area at the limits of CAHOOTS’s scope of work; in Eugene, the same dispatch system handles both emergency and nonemergency calls, in part because so many callers fail to grasp the distinction. One call I went on with Swift and Tessler was to check on the welfare of a young man with face tattoos who was reportedly acting strangely on the University of Oregon campus. The fire department and the police had been out to see him, without incident, but also without resolution: The man was still there, unsettling passersby, who kept calling him in as a potential threat to himself and others.

By the time CAHOOTS arrived, the man was lying on the grass with a small burning pile of latex gloves next to his head. When Swift jumped out of the van, alarmed, he sat halfway up and poked at the fire with a kitchen knife, then lay back down. Had the cops been called again, I thought, the incident might have played out differently, and landed in the next day’s paper: “A young man setting objects on fire was shot after brandishing a knife.” But that’s not how it went. Swift grabbed the knife, threw it well out of reach, and began talking to him.

Nathan Bemiller has been staying under an overpass near Washington Jefferson Park. He has gotten help from CAHOOTS several times. Eugene’s unhoused population accounts for 60 percent of CAHOOTS calls.

at 11 a.m. on a friday, I met Jennifer Peckels, one of the few cops in Eugene who walk their beat, to tag along as she patrolled a quadrant of restaurants and curbside gardens downtown. Born and raised in Eugene, Peckels is now in her fifth year on the force. Many of her interactions downtown are with a core group of people experiencing homelessness, mental-health crises, and addiction, or some combination thereof.

The rest of this article at:https://www.theatlantic.com/politic...-reduce-likelihood-of-police-violence/617477/

In Eugene, Oregon, a successful crisis-response program has reduced the footprint of law enforcement—and maybe even the likelihood of police violence.

- Story by Rowan Moore Gerety

- 8:00 AM ET

POLITICS - Photographs by Ricardo Nagaoka

Should american cities defund their police departments?

The question has been asked continually—with varying degrees of hope, fear, anger, confusion, and cynicism—since the killing of George Floyd on Memorial Day. It hung over the November election: on the right, as a caricature in attack ads (call 911, get a recording) and on the left as a litmus test separating the incrementalists from the abolitionists. “Defund the police” has sparked polarized debate, in part, because it conveys just one half of an equation, describing what is to be taken away, not what might replace it. Earlier this month, former President Barack Obama called it a “snappy slogan” that risks alienating more people than it will win over to the cause of criminal-justice reform.

Yet the defund idea cannot simply be dismissed. Its backers argue that armed agents of the state are called upon to address too many of society’s problems—problems that can’t be solved at the end of a service weapon. And continued cases of police violence in response to calls for help have provided regular reminders of what can go wrong as a result.

Annie Lowrey: Defund the police

In September, for example, new details came to light about the death of a man in Rochester, New York, which police officials had initially described as a drug overdose. Two months before Floyd’s death, Joe Prude had called 911 because his brother Daniel was acting erratically. Body-cam footage obtained by the family’s attorney revealed that the officers who responded to the call placed a mesh hood over Daniel’s head and held him to the ground until he stopped moving. He died a week later from “complications of asphyxia in the setting of physical restraint,” according to the medical examiner. Joe Prude had called 911 to help his brother in the midst of a mental-health crisis. “I didn’t call them to come help my brother die,” he has said.

A few weeks after a video showing Daniel Prude’s asphyxiation was made public, police in Salt Lake City posted body-cam footage that captured the moments before the shooting of a 13-year-old autistic boy. The boy’s mother had called 911 seeking help getting him to the hospital. While she waited outside, a trio of officers prepared to approach the home. One of them hesitated. “If it’s a psych problem and [the mother] is out of the house, I don’t see why we should even approach, in my opinion,” she said. “I’m not about to get in a shooting because [the boy] is upset.” Despite these misgivings, the officers pursued the distressed 13-year-old into an alley and shot him multiple times, leavinghim, his family has said, with injuries to his intestines, bladder, shoulder, and both ankles.

Neither these catastrophic outcomes nor the misgivings of police themselves have produced an answer to the obvious question: How should society handle these kinds of incidents? If not law enforcement, who should intervene?

Left: A sign displays the number to dial for CAHOOTS. Right: Dennis Ekanger, a co-founder of the White Bird Clinic.

One possible answer comes from Eugene, Oregon, a leafy college town of 172,000 that feels half that size. For more than 30 years, Eugene has been home to Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets, or CAHOOTS, an initiative designed to help the city’s most vulnerable citizens in ways the police cannot. In Eugene, if you dial 911 because your brother or son is having a mental-health or drug-related episode, the call is likely to get a response from CAHOOTS, whose staff of unarmed outreach workers and medics is trained in crisis intervention and de-escalation. Operated by a community health clinic and funded through the police department, CAHOOTS accounts for just 2 percent of the department’s $66 million annual budget.

When I visited Eugene one week this summer, city-council members in Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Houston, and Durham, North Carolina, had recently held CAHOOTS up as a model for how to shift the work of emergency response from police to a different kind of public servant. CAHOOTS had 310 outstanding requests for information from communities around the country.

Read: Why Minneapolis was the breaking point

A pilot program modeled in part on CAHOOTS recently began in San Francisco, and others will start soon in Oakland, California, and Portland, Oregon. Even the federal government has expressed interest. In August, Oregon’s senior senator, Ron Wyden, introduced the CAHOOTS Act, which would offer Medicaid funds for programs that send unarmed first responders to intervene in addiction and behavioral-health crises. “It’s long past time to reimagine policing in ways that reduce violence and structural racism,” he said, calling CAHOOTS a “proven model” to do just that. A police-funded program that costs $1 out of every $50 Eugene spends on cops hardly qualifies as defunding the police. But it may be the closest thing the United States has to an example of whom you might call instead.

Andrew Ferguson: ‘Defund the police’ does not mean defund the police. Unless it does.

A pile of belongings on the sidewalk in a Eugene neighborhood bears a note: “I’m going to White Bird.” The White Bird Clinic runs the CAHOOTS crisis-response program.

in 1968, Dennis Ekanger was a University of Oregon graduate student finishing up an internship as a counselor for families with children facing charges in the state’s juvenile-justice system when he started to get calls in the middle of the night.

Through his work in court, word had spread that “I knew something about substance-abuse problems,” Ekanger told me recently. Anxious mothers were arriving at his doorstep desperate for help but afraid to go to the authorities. It was a turbulent time in Eugene, with anti-war protests on the University of Oregon campus and a counterculture that spilled over into the surrounding neighborhoods in the form of tie-dye, pot smoke, and psychedelic drugs.

The following year, Ekanger and another student in the university’s counseling-psychology program, Frank Lemons, met with a prominent Eugene doctor who agreed to help them mount a more organized response by recruiting local health-care providers to volunteer their time. Ekanger went to San Francisco to visit a new community health clinic in Haight-Ashbury that had pioneered such a model, offering free medical treatment to anyone who walked in. Back in Oregon, Ekanger and Lemons each put up $250 and signed a lease on a dilapidated two-story Victorian near downtown.