https://www.polygon.com/comics/2019/4/4/17888520/two-captain-marvel-shazam-dc-warner-bros-comics

There are two Captain Marvels — this is the amazing story of why

It’s the story of the entire history of American comics

By Susana Polo@NerdGerhl Apr 4, 2019, 1:26pm EDT

Graphics by James Bareham

SHARE

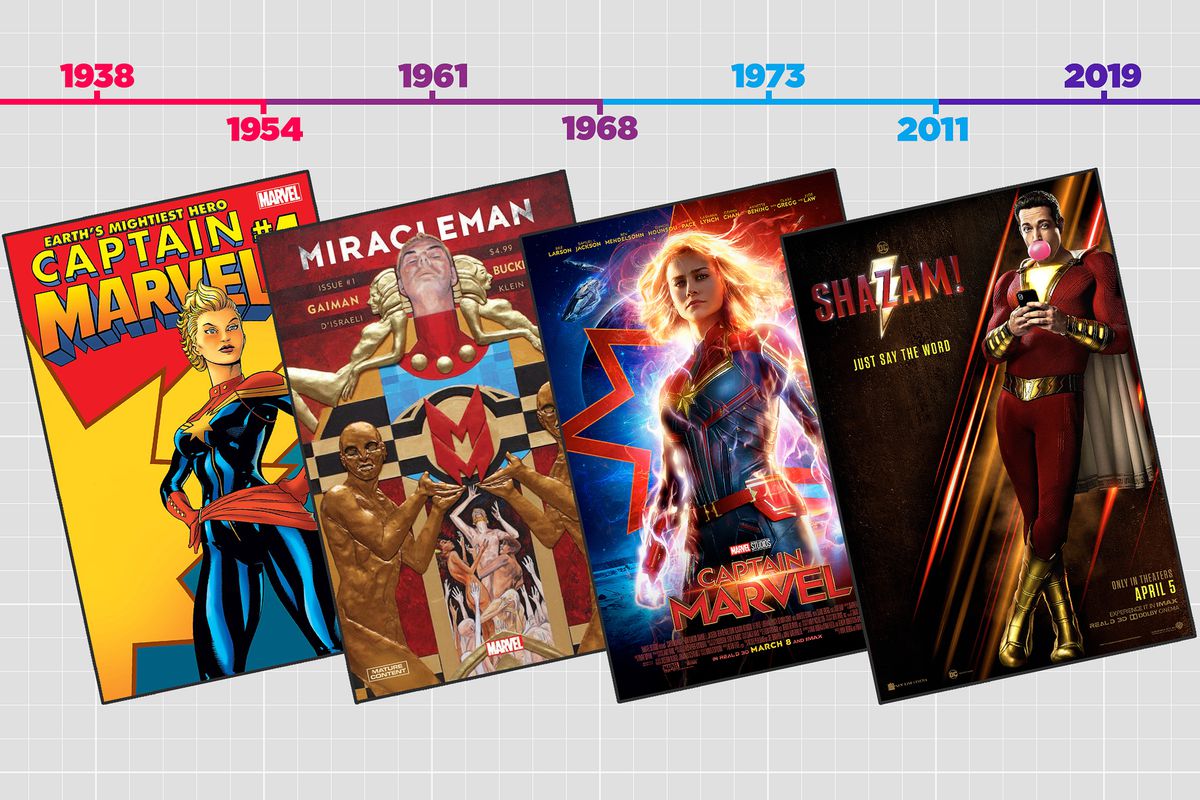

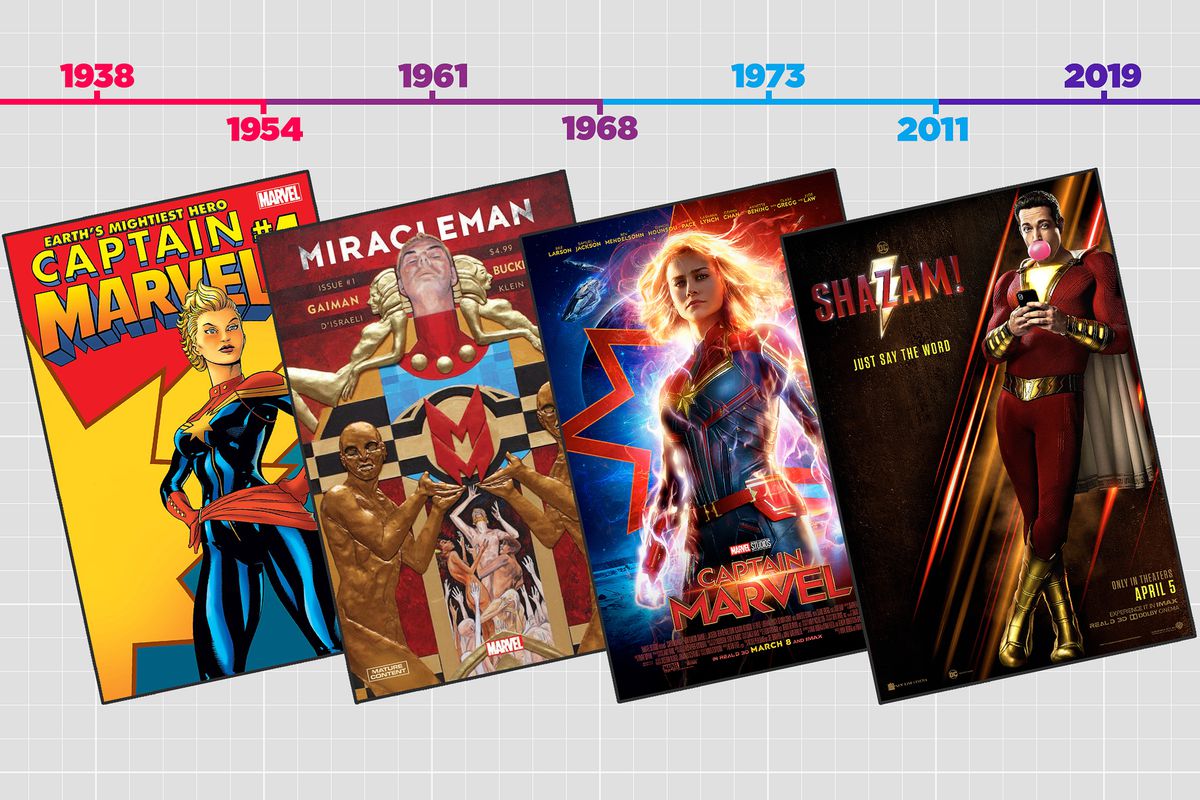

They say that life is stranger than fiction, but I know it to be true; because both Marvel and DC Comics have characters known as “Captain Marvel,” and in 2019, both of those characters have feature films out within a month of each other.

Even if you don’t know anything about comics, you may have heard that the lead character of Warner Bros.’ Shazam! used to be called “Captain Marvel,” just like the lead character of Marvel Studios’ Captain Marvel. Someone might even have explained to you that this is connected to a decades-long trademark Cold War between DC and Marvel Comics, or that it’s a primary reason why Marvel has published a Captain Marvel book for so long even though the character has never really been a consistent hit.

But the story of the Captain Marvels begins decades before Marvel Comics was even calling itself “Marvel Comics,” and it’s much, much wilder than you could ever expect. Among other things, it involves Superman, Spawn creator Todd McFarlane, the UK’s Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act of 1955, the word “atomik” spelled backwards, and preeminent United States legal scholar, Judge Learned Hand.

The story of the Captain Marvels is the story of the American superhero itself, from its 1938 origins to its modern explosion across the silver screen. The ripple effect shows up just about everywhere; for instance, there is a direct line of causation from the creation of the character known as Shazam and the very existence of Alan Moore’s Watchmen.

So, without further ado, the answer to the innocent question “Why are there two Captain Marvels?”

1938-1954: THE FIRST FEUD

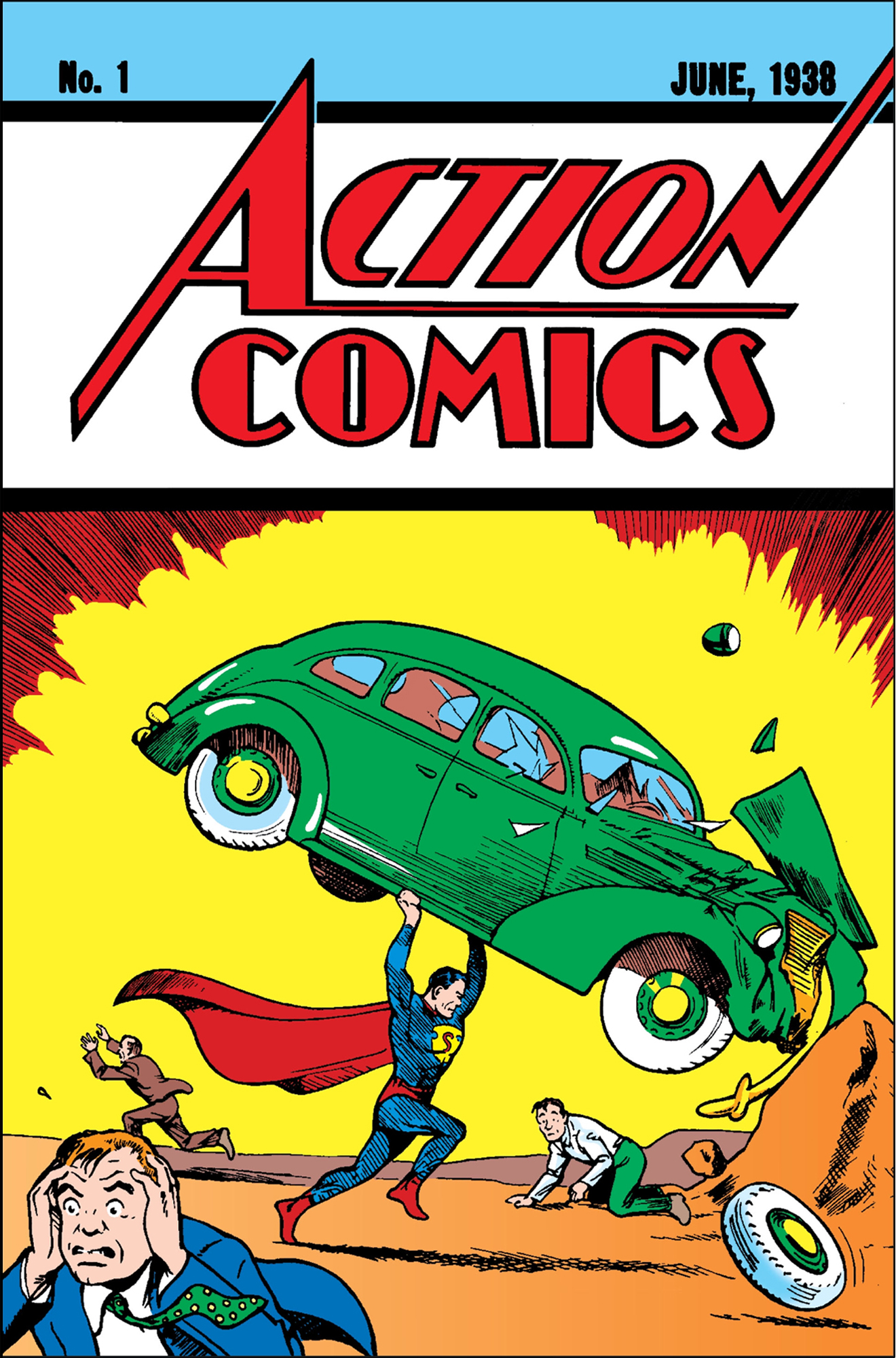

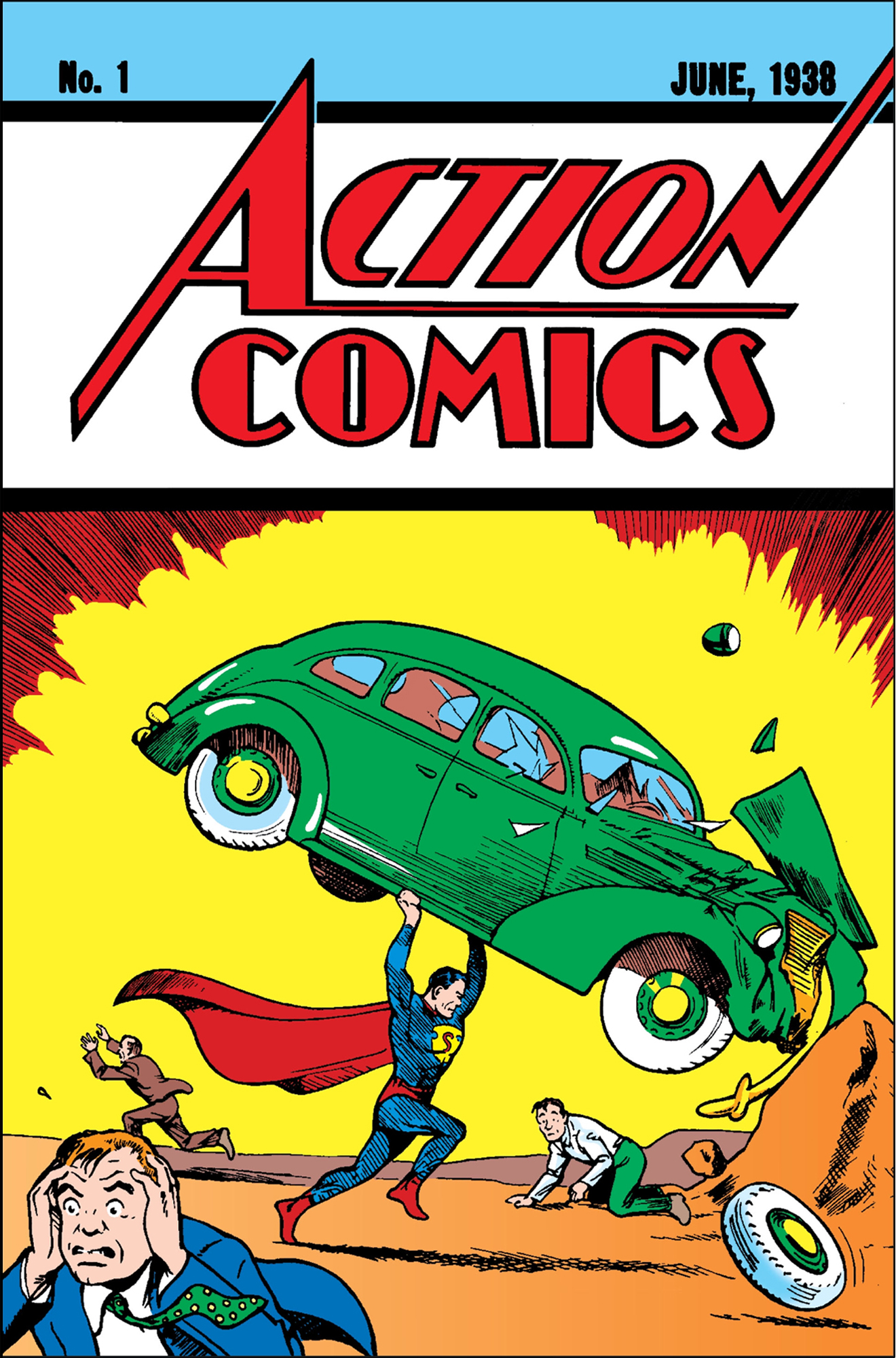

The 1938 publication of Action Comics #1, featuring the first appearance of Superman, prompted many writers and artists to try their hand at capturing the magic of the miraculously gifted crime-fighter. In swift succession, Siegel and Shuster’s contemporaries churned out Batman, Namor the Sub-Mariner, Sandman, Blue Beetle, the Flash, Hawkman, and more.

A NOTE ON NAMES

In this piece, we will be calling all characters by the name that they used in the time period we’re talking about when we name them.

If we’re talking about Shazam in the time when he was called Captain Marvel, we’ll call him Captain Marvel. If we’re talking about Miracleman in the time when he was called Marvelman, we’ll call him Marvelman. If we’re talking about Marvel Comics’ Captain Marvel, we’ll call him Captain Marvel.

After giving it some thought, this actually seemed less confusing than the alternatives.

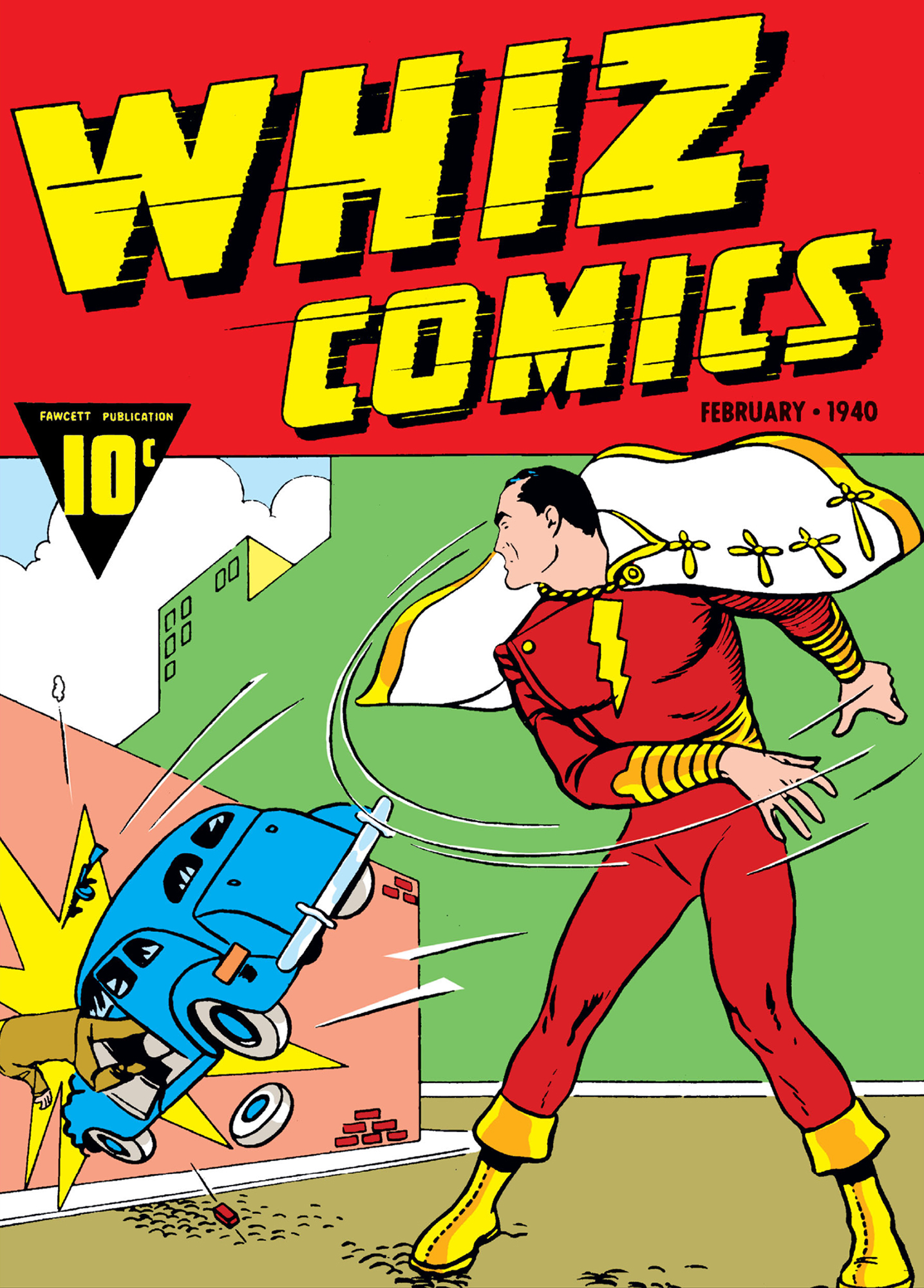

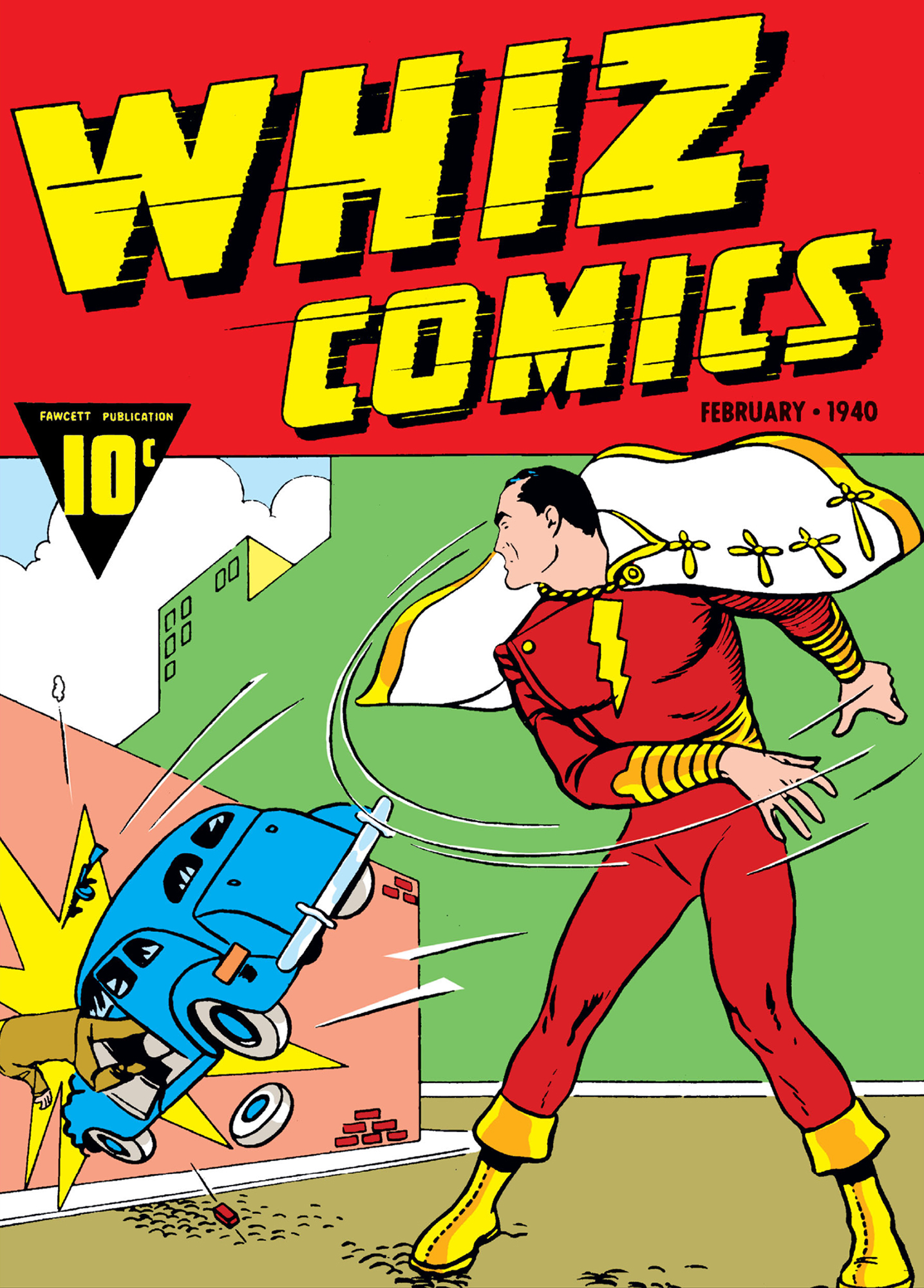

And in 1939, C.C. Beck and Bill Parker created a hero called Captain Marvel for Fawcett Publications’ Whiz Comics #2. By way of a magical subway train, the orphaned and homeless paper boy Billy Batson entered the Rock of Eternity, where dwelled the wise wizard Shazam. For his pureness of heart, Shazam endowed Billy with the power of his name, an acrostic for (the wisdom of) Solomon, (the strength of) Hercules, (the stamina of) Atlas, (the power of) Zeus, (the courage of) Achilles, and (the speed of) Mercury. When Billy said “Shazam!”, a crash of thunder and lightning swapped him out for Captain Marvel, the world’s mightiest mortal. When Captain Marvel said “Shazam!,” another crash brought Billy Batson back to reality.

As the success of Robin, the Boy Wonder, would prove a year later, the new genre of superheroes lacked a proxy for children to see themselves in the story. Billy Batson’s ability to say a magic word and summon a champion of good was that point of connection for Captain Marvel. The hero had an upbeat personality, and he quickly acquired an equally upbeat cast of characters known as the Marvel Family — including Mary Marvel, Uncle Marvel, and Captain Marvel, Jr. — whose adventures skewed closer to Windsor McCay than Bob Kane. Fawcett and Whiz Comics had a hit on their hands.

But DC Comics (then National Comics Publications) was not happy about Captain Marvel. They were even less happy when his comics began to outsell Superman comics.

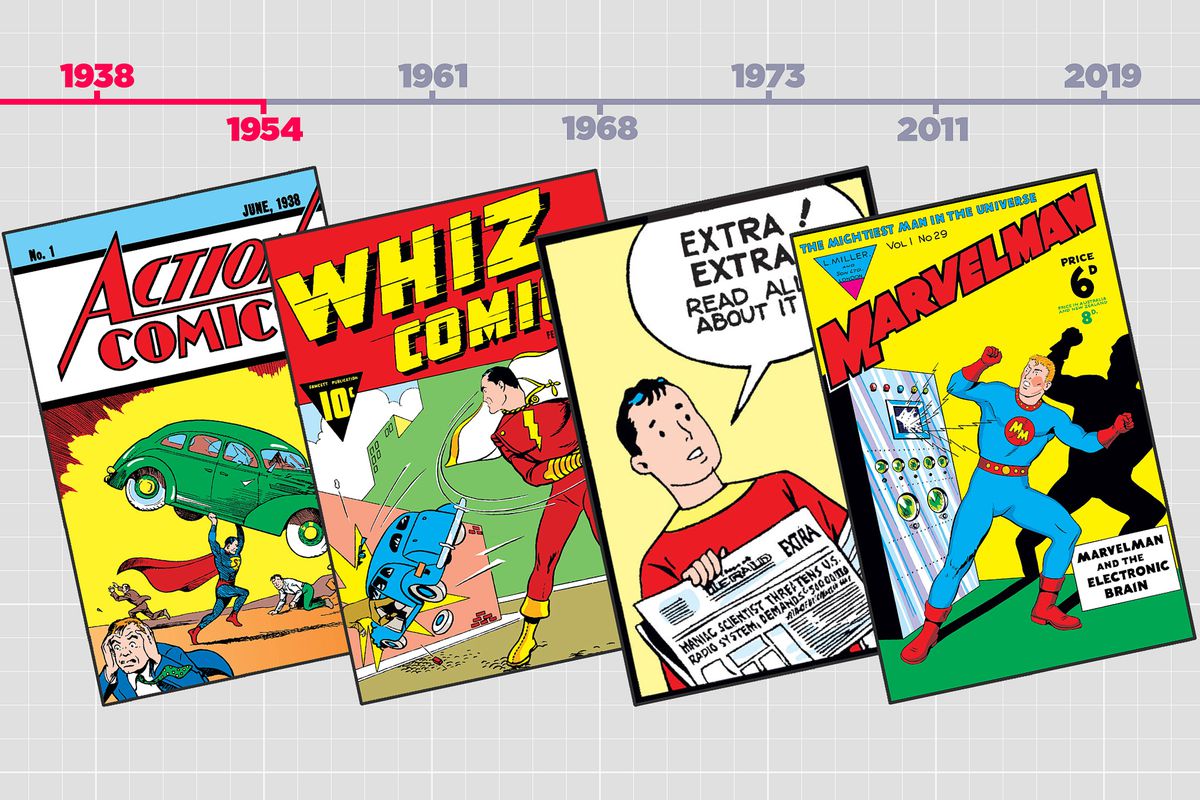

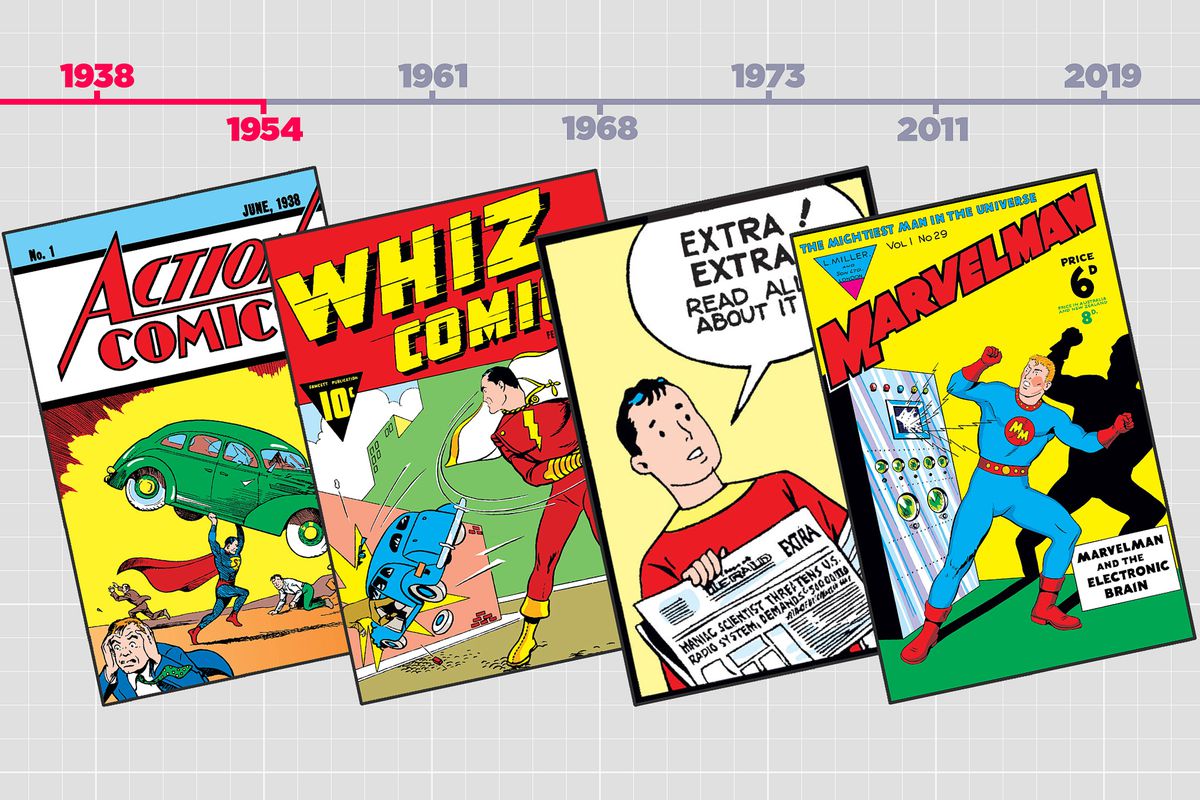

The covers of Action Comics #1 and Whiz Comics #1, the debut issues of Superman and Captain Marvel

Captain Marvel was a square-jawed, black-haired figure in a brightly-colored, close-fitting costume. He was immensely strong, and could fly and shrug off bullets like rainwater. On the cover of his first comic, the hero tosses a car like it’s a cardboard box, and by the end of his first adventure, Billy Batson had gained a job as a reporter, for a radio station.

National Comics sued Fawcett for copyright infringement in 1941. The suit spent years winding its way through the American legal system, as Captain Marvel stories expanded and expanded, even switching to a then-unheard-of twice-monthly publishing schedule.

National and Fawcett finally went to trial in 1948, and the judge agreed that Fawcett boldly copied Superman when it created Captain Marvel. But in a double take for the ages, he also ruled that the similarities didn’t matter. National had failed to copyright some Superman newspaper strips, and so the southern District Court of New York ruled that the company had abandoned its copyright, and therefore its claim against Fawcett was not valid.

Needless to say, National appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where it came to the bench of none other than famed American legal scholar, Judge Billings Learned Hand. Hand ruled that National’s copyright was valid, and that its claim had merit — Captain Marvel could very well be an infringement of Superman — and sent it back to a lower court for retrial.

But, in 1951, two important things had become clear: First, the odds that a third judge would rule that Fawcett had infringed on National’s copyright seemed high. Second, superhero sales had slid considerably from their 1940s heyday, as the public mood turned against comics, and politicians and pundits sought to link them with post-war fears of juvenile delinquency.

Rather than go to trial a third time, Fawcett settled out of court, paying National $400,000. Adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly four million dollars. Fawcett also agreed to never publish a Captain Marvel comic again. In 1953, the company would actually get out of the comics publishing business entirely.

Outside of the legal rulings, the question of whether the creators of Captain Marvel intentionally ripped off Superman is an open one. Certainly, Captain Marvel does not seem infringing today, in a fully grown superhero genre in which Superman’s powers of flight, strength, and invulnerability are almost a basic template for the form.

But Captain Marvel was about to move into a new era: A new era of ripoffs, a new era of comics history, and an entirely new country.

1954-1972: ENTER MAR-VELL

As the Captain Marvel drama cooled down in America, things were heating up across the pond.

In 1945, English publisher L. Miller & Son had acquired the license to reprint Fawcett’s bright and cheerful Captain Marvel comics in the UK, to a receptive audience of children who had just survived World War II. Nine years and a few stateside lawsuits later, Captain Marvel remained the company’s biggest seller. But by 1954, with Fawcett out of the business of comics entirely, L. Miller & Son had run out of material.

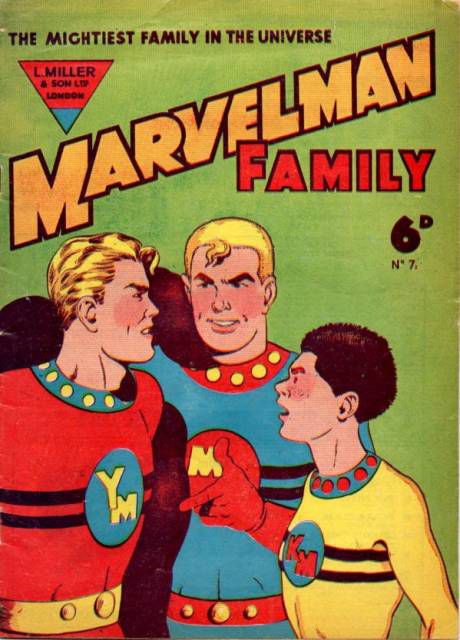

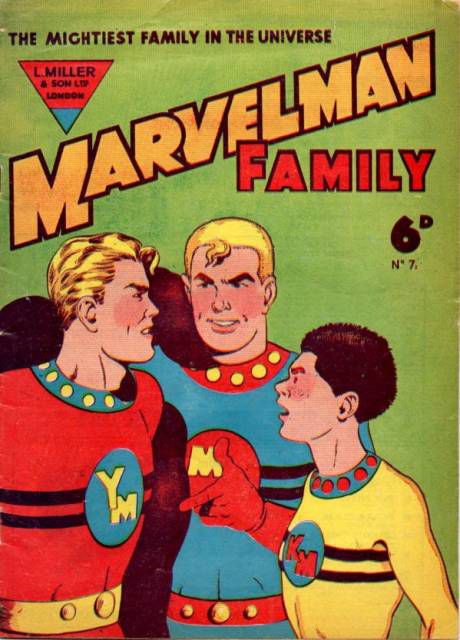

Marvelman Family #7

Mick Anglo/ L. Miller & Son

So, Leonard Miller himself hired writer-artist Mick Anglo to create a knockoff of Captain Marvel — yes, a knockoff of a character that had just spent 10 years deflecting accusations of being a knockoff — to lead his own book. Anglo delivered the very-atomic-age-inflected Marvelman, in which an astrophysicist uses atomic energy to give young reporter Micky Moran the ability to transform into the superhero Marvelman whenever he says the word “KIMOTA.” That is, “atomic,” but backwards and with a K. There was even a “Marvelman, Jr.” or, Young Marvelman

For about a decade, Marvelman comics were a touchstone in the lives of UK kids, thanks in part to the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act of 1955, the nadir of the UK’s own anti-comics fervor. The Act limited American comics imports from reaching British shores for quite some time, allowing for the flourishing of locally sourced heroes like Marvelman. But that wouldn’t last forever.

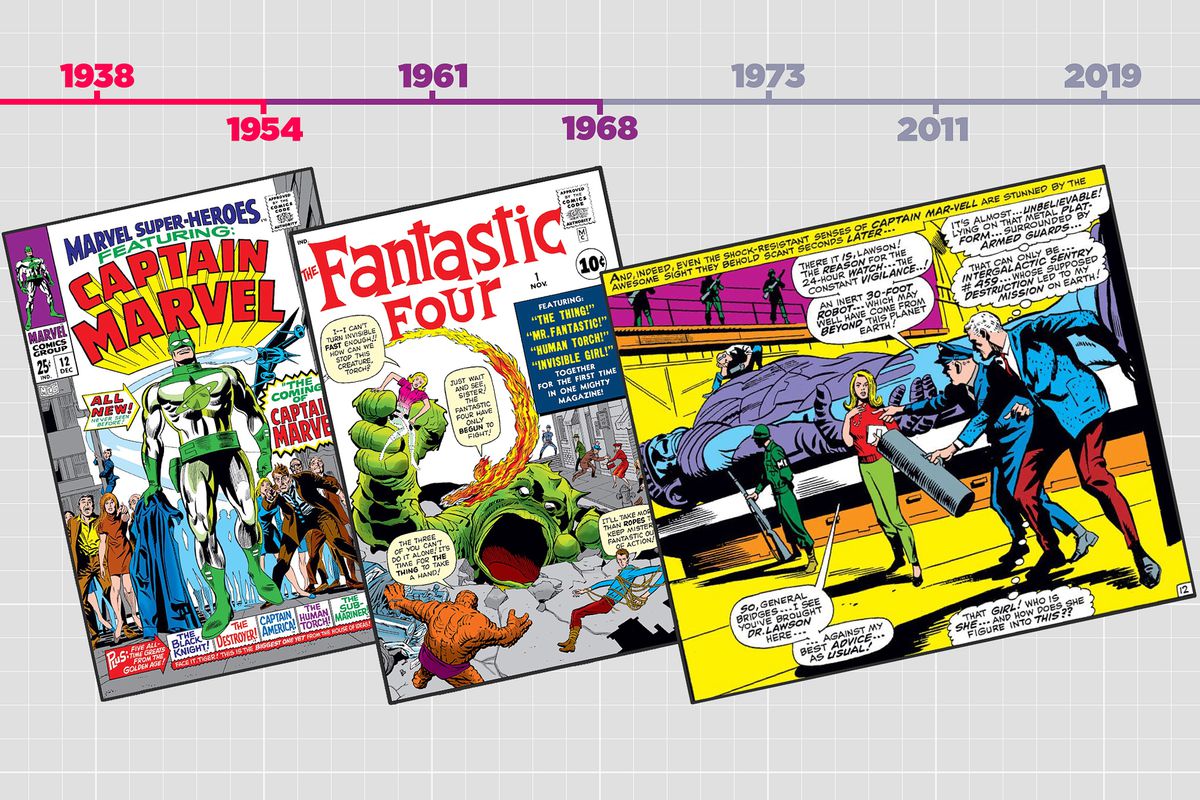

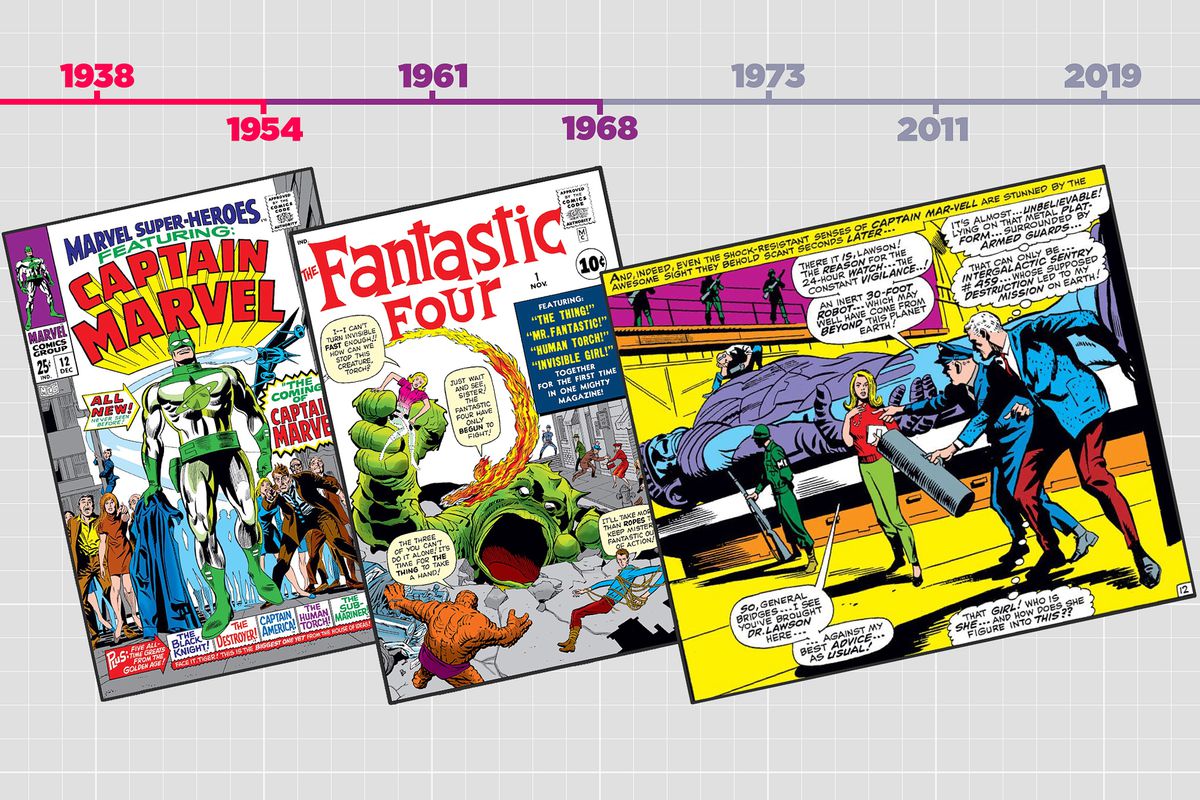

In 1961, the American publisher Timely Comics began branding their Journey Into Mystery and Patsy Walker series as “Marvel Comics.” That moniker later extended to the company’s brand new hit, a superhero team comic called Fantastic Fourfrom a couple of guys named Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. The Marvel revolution was in motion.

By that time, anti-comics fervor had cooled in the US and the UK, and Marvel Comics reprints — handled by the company’s UK division, rather than being licensed to a local publisher— were immensely popular. Unable to compete with the American invasion, Miller & Son went bankrupt in 1963, and Marvelman went with them. But this was not the end of Captain Marvel or his imitators. Not by a long shot.

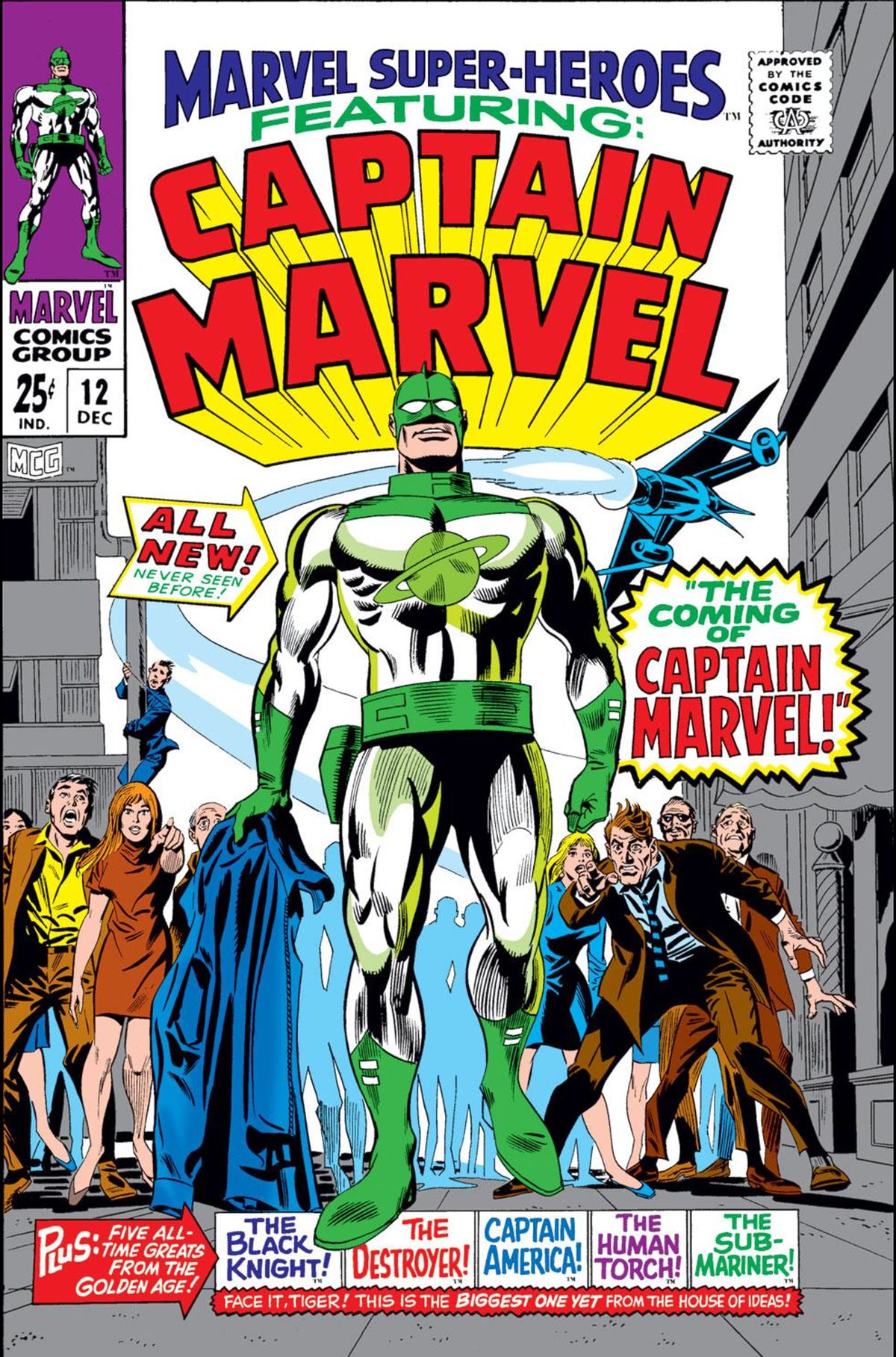

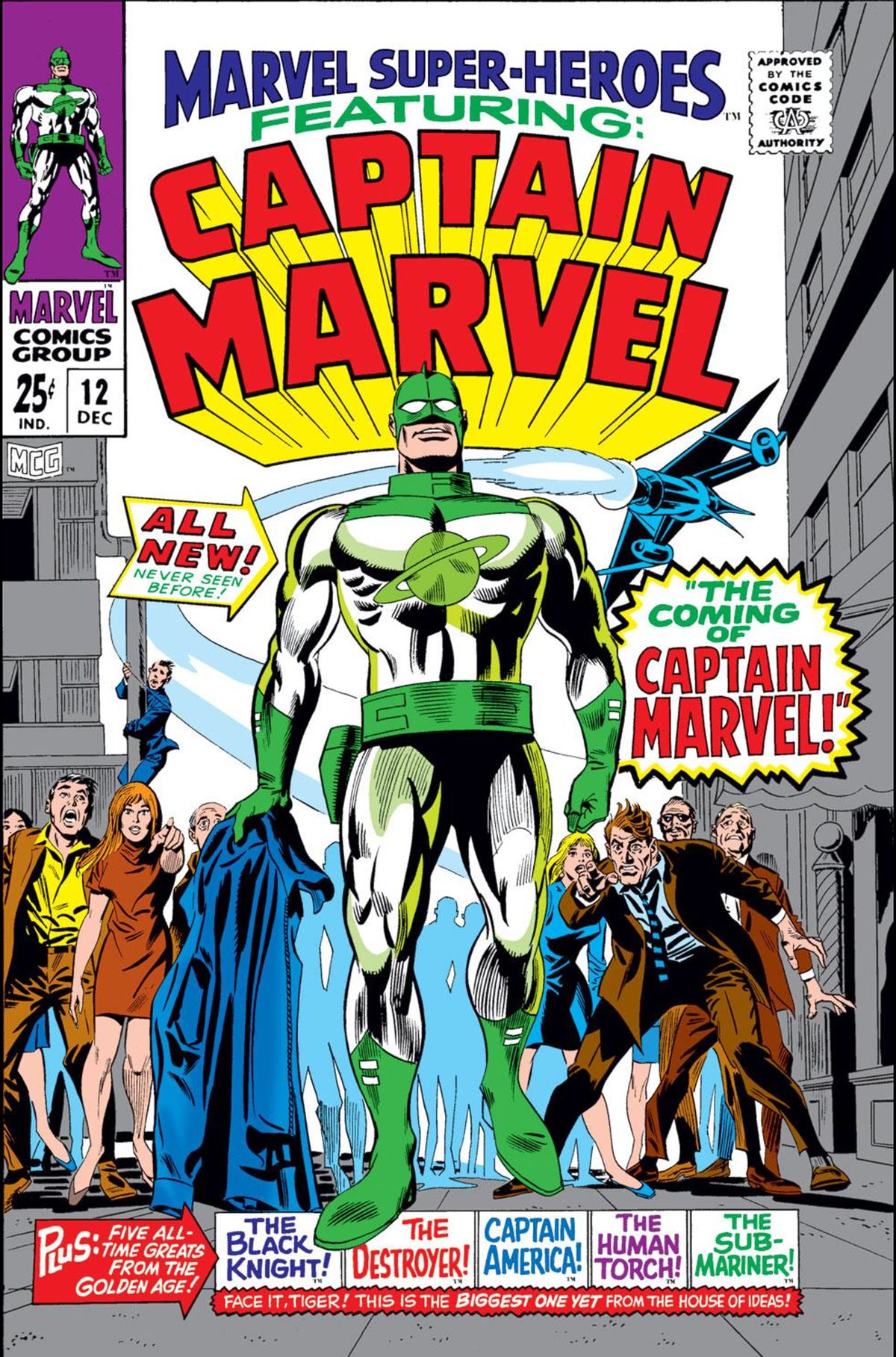

Marvel Super-Heroes #12, the debut issue of Captain Marvel (Mar-Vell).

Gene Colan, Frank Giacoia, Stan Goldberg, Artie Simek/Marvel Comics

In 1967, Marvel Comics, the rebranded name of Timely Comics, discovered that Fawcett Publications had allowed its trademark on the phrase “Captain Marvel” to lapse. 16 years after Captain Marvelceased production, Marvel Comics began printing a series under the same name, created by Stan Lee and Gene Colan, about the adventures of an alien whose given name was Mar-Vell. To the citizens of Earth, like air force security officer Carol Danvers would one day be, he was the superhero Captain Marvel.

Marvel exploited the key differences between a trademark and copyright. Trademarks are designed to cover words, phrases, graphics and other brand signifiers, while copyrights are designed to protect ownership of a piece of intellectual property — a story, character, song or other work. Trademarks have to be defended, sometimes zealously; the owner has to show that the trademark is in regular use and that it has not become genericized, or other businesses can defend their own right to use it.

Fawcett still held the copyright to Captain Marvel — his origin story, his costume, and his printed comics — but Marvel Comics now had the right to use “Captain Marvel” as branding. And two years after his debut, when sales were slumping, Roy Thomas and Gil Kane gave Marvel’s Captain Marvel a new gimmick, in which he became trapped in the Negative Zone. The only way for him to fight crime in our dimension was to swap places with a heroic kid in a red shirt and blue pants — mirroring Billy Batson’s subway origin story, but with perennial Avengers sidekick Rick Jones and space technology instead of magic.

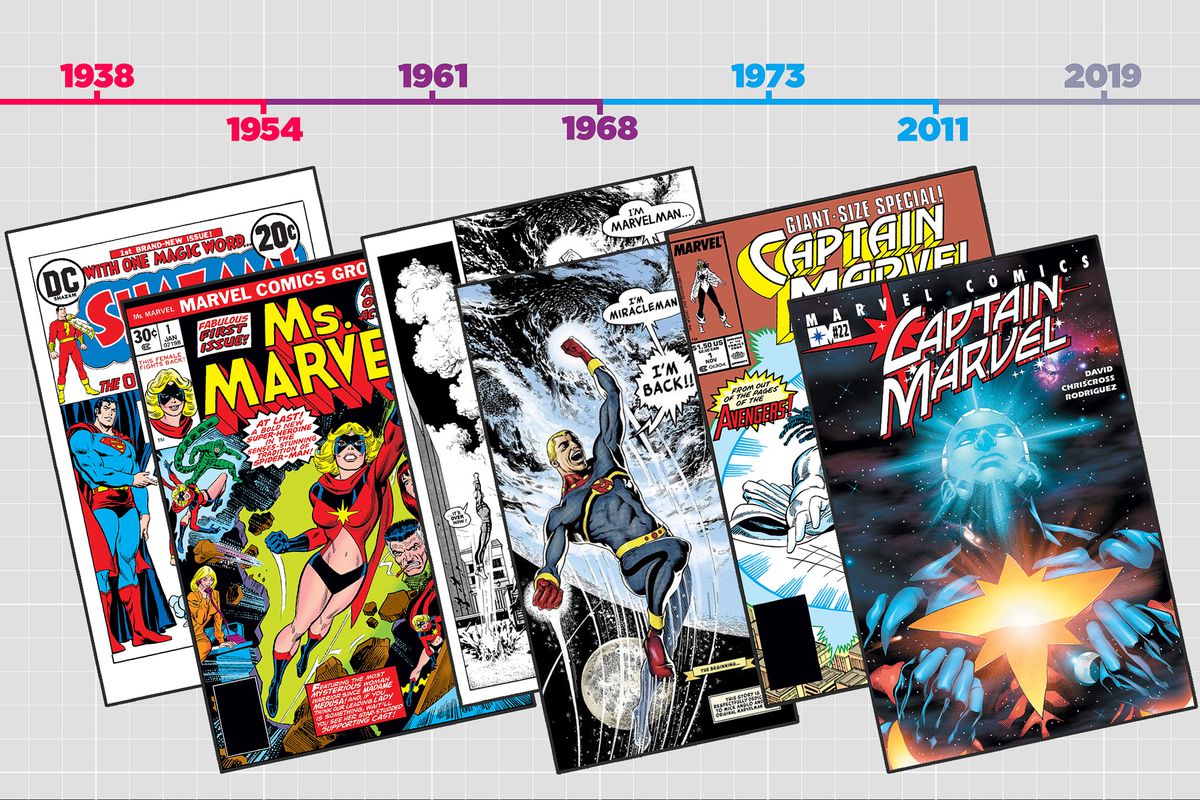

The cute homage was also a deep cut; in 1969, only diehard comic readers would have remembered C.C. Beck’s Captain Marvel. There hadn’t been a new Captain Marvel story — at least, not one about a guy in a red suit who shouted “SHAZAM!” — in almost 20 years. And there would probably never have been one again, if not for DC Comics. In 1972, the comic giant licensed the character from Fawcett Publications, and began printing a series about a guy named Captain Marvel who wore a red suit and shouted “SHAZAM!”

Yes, the same company that had driven Fawcett out of the comic book business 21 years prior because Captain Marvel was similar to Superman went to its opponent and worked out a deal to print Captain Marvel comics. But DC’s license only covered the copyright, not the trademark, and this divergence of brand identity would define both Captain Marvels for nearly 40 years.

1972-2011: THE SECOND FEUD

DC’s first Captain Marvel series was called Shazam!, named so to avoid brushing up against Marvel Comics’ trademark of “Captain Marvel.” When DC editor Carmine Infantino gave the book the subtitle “The Original Captain Marvel,” Marvel sent a cease and desist letter to DC, to dispel any doubt about how prickly the competition was about to get. The book’s branding was changed to “The World’s Mightiest Mortal” for issue #15, but within the pages of Shazam!, Billy Batson still summoned a hero who went by the name “Captain Marvel.”

DC had an easier row to hoe than Marvel. They had the license to the copyright, and, in 1991, DC purchased the full rights to Captain Marvel and associated characters outright. Copyrights don’t need to be defended as assiduously as trademarks, and there were long periods between 1972 and 2011 during which Captain Marvel appeared only in backup stories of other books, as a member of a team, or not at all. His original creators struggled to gain an audience for the character in his classic incarnation, and he only really had one successful ongoing series, Jerry Ordway’s The Power of Shazam!, which ran from 1995 to 1999. (He also had a CBS TV series that ran from 1974 to 1976.)

From The Power of Shazam! (1994).

Jerry Ordway/DC Comics

Like Warner Bros.’ Shazam! film, DC creators (in a combination of work from Keith Giffen, J. M. DeMatteis, and Roy and Dan Thomas) made a slight but significant tweak to the character. From 1987 onward, Captain Marvel and Billy Batson were no longer two different people. Captain Marvel had reached the ultimate conclusion of Billy Batson’s original appeal as an audience surrogate: He was now literally a child in the body of an adult superhero.

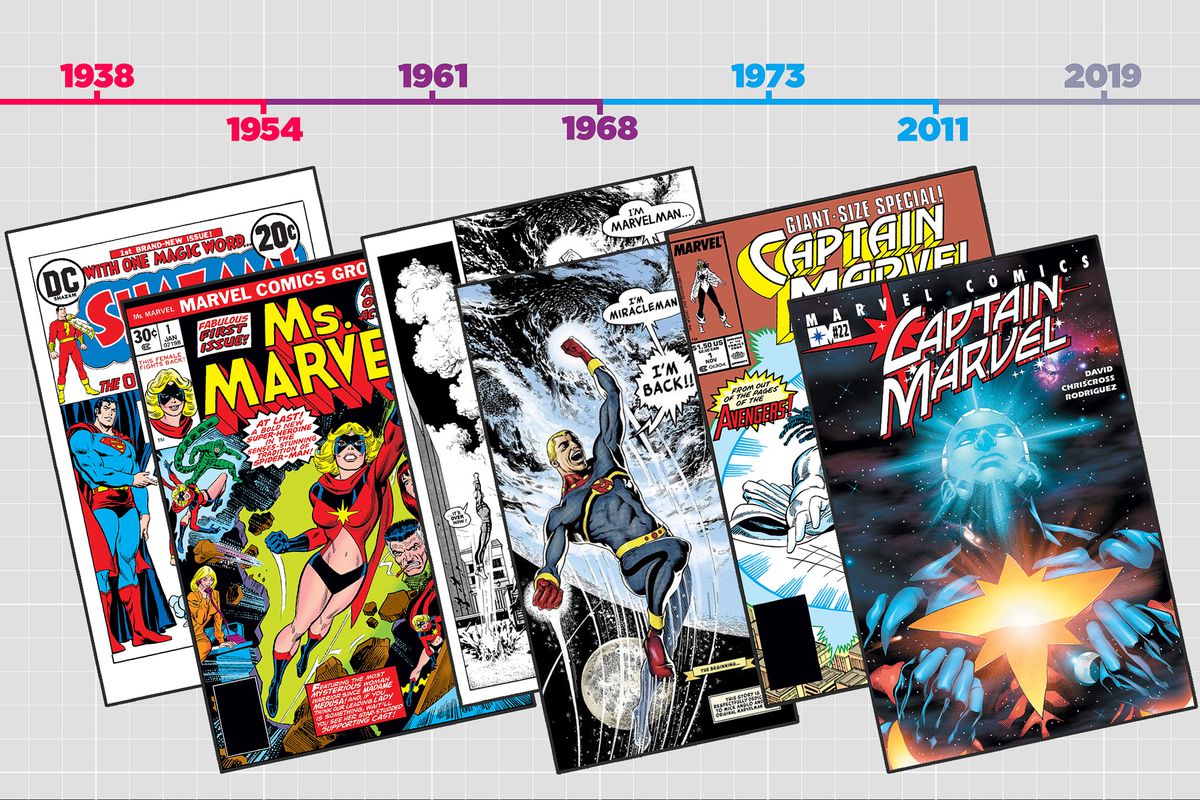

In 1972, the moment DC Comics started publishing Shazam!, Marvel Comics editorial realized the situation: Given an inch, DC would eagerly yank back the trademark to their character’s name. If Marvel wanted to keep it, it would have to regularly publish a comic book called Captain Marvel, regardless of that book’s popularity, potentially forever. So that’s exactly what the company did.

Marvel’s first Captain Marvel series ended in 1979. In 1982, Marvel used the first book in its groundbreaking Marvel Graphic Novel line, Death of Captain Marvel, to showcase Mar-Vell’s tragic death from cancer. In 1985, the company reprinted a bunch of old Mar-Vell stories under the title Life of Captain Marvel. In 1989 and 1994, Marvel published one-shot stories about Mar-Vell’s first successor, Monica Rambeau (played by Akira Akbar in Marvel Studios’ Captain Marvel). In 1995 and 1997, Marvel published two short miniseries with the Captain Marvel name. In 2000, writer Peter David finally struck ongoing series gold for the first time in 20 years, with a Captain Marvel book about Genis-Vell, the son (sort of) of Mar-Vell, and his sister (sort of) Phyla-Vell, that ran for four years. In 2008, Marvel published another miniseries called Captain Marvel,about a shape-shifting Skrull sleeper agent who mistakenly believed himself to be Mar-Vell.

Captain Marvel’s England presence offers another even more complicated branch of this story. In 1982, a man by the name of Derek “Dez” Skinn, former editor in chief of Marvel’s UK division, obtained verbal permission from Mick Anglo — that’s the guy who created Marvelman, the knock off of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel — to make new Marvelman stories.

Skinn was looking for content for his putative black and white anthology comics series, Warrior, and thought that a modern relaunch of a UK cult classic would help sell copies. The black and white comics anthology series was a big staple of British comics in the era; and although not as famous 2000 AD, home of Judge Dread, Warrior’s 26 issues made a mark on comics history, not least for being the original publisher of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta.

From Moore’s Marvelman stories.

Alan Moore, Garry Leach/Warrior

Speaking of Moore, the young writer was the third person Skinn approached about a modernized Marvelman, and the first who showed the slightest interest in it. With Garry Leach and Alan Davis drawing, Moore wrote 21 story installments for Warrior, featuring an adult Micky Moran as an unhappy man who dreams of flying. Over the course of Moore’s story, Moran recovers his memories of being Marvelman, but also finds out that his cheerful adventures were a brain-washed delusion inflicted on him when he was a boy, by scientists attempting to use alien technology to place a nigh-all-powerful alien being under human control.

Moore’s dark, contemporary revival of the Golden Age Marvelman fiercely interrogated the very nature of the superhero myth, and, four years after he left Warrior, it was proof that he had the chops to tackle another project. Moore pitched Who Killed the Peacemaker?, a dark, contemporary revival of Charlton Comics’ Golden Age characters, to DC Comics. The company accepted, and the final series wound up with a different name: Watchmen.

Dez Skinn eventually licensed Moore’s Marvelman to American publisher Eclipse Comics, who began reprinting Moore’s work in the US in 1985. Except, just like DC Comics’ Captain Marvel, Eclipse could not call the book “Marvelman” without hearing from Marvel Comics’ lawyers. The entire series was renamed, colored, and its text relettered, to transform it into Miracleman.

Alan Moore’s Marvelman, now Miracleman.

Alan Moore, Garry Leach/Eclipse Comics

Under Eclipse, Moore continued writing his story — begun as Marvelman, now called Miracleman — and in 1988, was succeeded in writing duties by Neil Gaiman, who wrote the series until 1994, when Eclipse went bankrupt. In 1996, Eclipse’s assets, including Miracleman, were purchased by Spawn-creator and entrepreneur Todd McFarlane, and it was this purchase that embroiled the series in another of the comics world’s great intellectual property ownership battles.

Gaiman held that McFarlane had improperly compensated him for the co-creation of three Spawncharacters, and sued McFarlane for the rights to those characters and Miracleman in 2002. All profits from Gaiman’s 2003 Marvel Comics miniseries, Marvel 1602, went directly to Marvels and Miracles, an LLC Gaiman had formed for the purpose of sorting out who actually held the rights to Marvelman/Miracleman. After a court settled in Gaiman’s favor, Marvel Comics purchased the rights to Marvelman from Mick Anglo, in a much more legally binding way than Dez Skinn’s gentleman’s agreement.

So, in 2014, Marvel Comics began publishing reprint editions of Miracleman, a reprinted form of Marvelman (renamed out of fear of Marvel Comics’ lawyers), which was a modern revamp of the Golden Age Marvelman, which was an open knockoff of Captain Marvel, a character who belonged to DC Comics (after that same company used a lawsuit to bar his publication for 20 years), but whose name belonged to Marvel Comics, who had engaged in a Captain Marvel trademark/copyright cold war with DC for 40 years. Where does it all end?

2011-NOW: ENTER CAROL DANVERS

In 2011, DC Comics kicked off its first line-wide continuity reboot in over 25 years, an era known as the New 52. Captain Marvel came along, except … nobody was calling him Captain Marvel anymore. When Billy Batson and family appeared in backup stories to the New 52’s Justice League, the character’s name was simply “Shazam.”

In 2012, writer Geoff Johns told Newsarama that the name change was for multiple reasons, but “one is that everybody thinks he’s called Shazam already, outside of comics ... you know, every comic book he’s in right now has Shazam on the cover.”

Right around the time that Captain Marvel finally, officially, became Shazam, Marvel Comics struck Captain Marvel gold. Kelly Sue DeConnick and Dexter Soy introduced Carol Danvers — formerly the superhero Ms. Marvel, formerly a supporting character in Marvel’s first Captain Marvel series — the newest character to wear the boots of Captain Marvel, and her series was a runaway hit. In 2014, Marvel Studios announced that it had a Captain Marvel movie in production, though delays would bump it from an original July 6, 2018 release date.

In 2017, Warner Bros. announced that David F. Sandberg would be directing Shazam!, rescuing a project that had been in development long enough to be referred to as a “Captain Marvel movie.” Later in 2017, Marvel Comics announced that Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham would return to Miracleman to complete their final, interrupted arc once and for all.

On March 8, 2019, Captain Marvel hit theaters. On April 5, 2019, Shazam! will, too.

Superman and Shazam (then still called Captain Marvel) in 2005’s Superman/Shazam! First Thunder.

Judd Winick, Joshua Middleton/DC Comics

Superhero intellectual property battles didn’t start with Marvel Studios, Sony Pictures, and 20th Century Fox. The American comics industry was built on epic battles — over intellectual property.

Since the earliest days of comics, the largest publishers have ensured that artists had next to no ownership of their creations. That standard has only just begun to change in the past 30 years. Inventing intellectual property on a work-for-hire basis is simultaneously American comics’ greatest hurdle and, shamefully, a source of one of its greatest strengths.

The work-for-hire model has left creator after creator in the dust, especially now that characters like Rocket Raccoon, Venom, and Aquaman are billion-dollar properties. And yet, in superhero comics, passing a character from artist to artist and writer to writer is not just the primary way their stories survive, but the primary way they evolve. This is how superheroes have remained relevant for four generations of readers and counting.

the extreme of the ’90s. By this time, he wasn’t a character who was failing to evolve — he was a character who stood in interesting contrast to his peers. He was a welcoming throwback; nostalgia for a lost and perhaps nobler era.

In contrast, Marvel Comics’ endless churn of new revamps — Captain Marvel is an alien man! No, a human woman with energy powers! No, a genetically engineered alien! No, his sister; a skrull; his worst enemy! — still took 40 years and half a dozen completely different incarnations to find a hit character in Captain Marvel.

The confusion from all of this still lingers. Today, Shazam’s Wikipedia article is still titled “Captain Marvel (DC Comics),” while you’ll find Marvel’s original Captain Marvel under “Captain Marvel (Mar-Vell).” Today, Carol Danvers is inarguably the most famous Captain Marvel. On Wikipedia’s “Captain Marvel (disambiguation)” page, she is listed not first, not second, or third, but 12th.

But we’ve reached a new section of the timeline. As they’ve done for B-list Marvel characters and iterations of Batman, Captain Marvel and Shazam! will mainstream two characters with entangled history and clear up 80 years of behind-the-scenes drama.

And the next time you shake your head at a superhero’s complicated backstory, just remember: It was probably even more complicated in real life.

There are two Captain Marvels — this is the amazing story of why

It’s the story of the entire history of American comics

By Susana Polo@NerdGerhl Apr 4, 2019, 1:26pm EDT

Graphics by James Bareham

SHARE

They say that life is stranger than fiction, but I know it to be true; because both Marvel and DC Comics have characters known as “Captain Marvel,” and in 2019, both of those characters have feature films out within a month of each other.

Even if you don’t know anything about comics, you may have heard that the lead character of Warner Bros.’ Shazam! used to be called “Captain Marvel,” just like the lead character of Marvel Studios’ Captain Marvel. Someone might even have explained to you that this is connected to a decades-long trademark Cold War between DC and Marvel Comics, or that it’s a primary reason why Marvel has published a Captain Marvel book for so long even though the character has never really been a consistent hit.

But the story of the Captain Marvels begins decades before Marvel Comics was even calling itself “Marvel Comics,” and it’s much, much wilder than you could ever expect. Among other things, it involves Superman, Spawn creator Todd McFarlane, the UK’s Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act of 1955, the word “atomik” spelled backwards, and preeminent United States legal scholar, Judge Learned Hand.

The story of the Captain Marvels is the story of the American superhero itself, from its 1938 origins to its modern explosion across the silver screen. The ripple effect shows up just about everywhere; for instance, there is a direct line of causation from the creation of the character known as Shazam and the very existence of Alan Moore’s Watchmen.

So, without further ado, the answer to the innocent question “Why are there two Captain Marvels?”

1938-1954: THE FIRST FEUD

The 1938 publication of Action Comics #1, featuring the first appearance of Superman, prompted many writers and artists to try their hand at capturing the magic of the miraculously gifted crime-fighter. In swift succession, Siegel and Shuster’s contemporaries churned out Batman, Namor the Sub-Mariner, Sandman, Blue Beetle, the Flash, Hawkman, and more.

A NOTE ON NAMES

In this piece, we will be calling all characters by the name that they used in the time period we’re talking about when we name them.

If we’re talking about Shazam in the time when he was called Captain Marvel, we’ll call him Captain Marvel. If we’re talking about Miracleman in the time when he was called Marvelman, we’ll call him Marvelman. If we’re talking about Marvel Comics’ Captain Marvel, we’ll call him Captain Marvel.

After giving it some thought, this actually seemed less confusing than the alternatives.

And in 1939, C.C. Beck and Bill Parker created a hero called Captain Marvel for Fawcett Publications’ Whiz Comics #2. By way of a magical subway train, the orphaned and homeless paper boy Billy Batson entered the Rock of Eternity, where dwelled the wise wizard Shazam. For his pureness of heart, Shazam endowed Billy with the power of his name, an acrostic for (the wisdom of) Solomon, (the strength of) Hercules, (the stamina of) Atlas, (the power of) Zeus, (the courage of) Achilles, and (the speed of) Mercury. When Billy said “Shazam!”, a crash of thunder and lightning swapped him out for Captain Marvel, the world’s mightiest mortal. When Captain Marvel said “Shazam!,” another crash brought Billy Batson back to reality.

As the success of Robin, the Boy Wonder, would prove a year later, the new genre of superheroes lacked a proxy for children to see themselves in the story. Billy Batson’s ability to say a magic word and summon a champion of good was that point of connection for Captain Marvel. The hero had an upbeat personality, and he quickly acquired an equally upbeat cast of characters known as the Marvel Family — including Mary Marvel, Uncle Marvel, and Captain Marvel, Jr. — whose adventures skewed closer to Windsor McCay than Bob Kane. Fawcett and Whiz Comics had a hit on their hands.

But DC Comics (then National Comics Publications) was not happy about Captain Marvel. They were even less happy when his comics began to outsell Superman comics.

The covers of Action Comics #1 and Whiz Comics #1, the debut issues of Superman and Captain Marvel

Captain Marvel was a square-jawed, black-haired figure in a brightly-colored, close-fitting costume. He was immensely strong, and could fly and shrug off bullets like rainwater. On the cover of his first comic, the hero tosses a car like it’s a cardboard box, and by the end of his first adventure, Billy Batson had gained a job as a reporter, for a radio station.

National Comics sued Fawcett for copyright infringement in 1941. The suit spent years winding its way through the American legal system, as Captain Marvel stories expanded and expanded, even switching to a then-unheard-of twice-monthly publishing schedule.

National and Fawcett finally went to trial in 1948, and the judge agreed that Fawcett boldly copied Superman when it created Captain Marvel. But in a double take for the ages, he also ruled that the similarities didn’t matter. National had failed to copyright some Superman newspaper strips, and so the southern District Court of New York ruled that the company had abandoned its copyright, and therefore its claim against Fawcett was not valid.

Needless to say, National appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where it came to the bench of none other than famed American legal scholar, Judge Billings Learned Hand. Hand ruled that National’s copyright was valid, and that its claim had merit — Captain Marvel could very well be an infringement of Superman — and sent it back to a lower court for retrial.

But, in 1951, two important things had become clear: First, the odds that a third judge would rule that Fawcett had infringed on National’s copyright seemed high. Second, superhero sales had slid considerably from their 1940s heyday, as the public mood turned against comics, and politicians and pundits sought to link them with post-war fears of juvenile delinquency.

Rather than go to trial a third time, Fawcett settled out of court, paying National $400,000. Adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly four million dollars. Fawcett also agreed to never publish a Captain Marvel comic again. In 1953, the company would actually get out of the comics publishing business entirely.

Outside of the legal rulings, the question of whether the creators of Captain Marvel intentionally ripped off Superman is an open one. Certainly, Captain Marvel does not seem infringing today, in a fully grown superhero genre in which Superman’s powers of flight, strength, and invulnerability are almost a basic template for the form.

But Captain Marvel was about to move into a new era: A new era of ripoffs, a new era of comics history, and an entirely new country.

1954-1972: ENTER MAR-VELL

As the Captain Marvel drama cooled down in America, things were heating up across the pond.

In 1945, English publisher L. Miller & Son had acquired the license to reprint Fawcett’s bright and cheerful Captain Marvel comics in the UK, to a receptive audience of children who had just survived World War II. Nine years and a few stateside lawsuits later, Captain Marvel remained the company’s biggest seller. But by 1954, with Fawcett out of the business of comics entirely, L. Miller & Son had run out of material.

Marvelman Family #7

Mick Anglo/ L. Miller & Son

So, Leonard Miller himself hired writer-artist Mick Anglo to create a knockoff of Captain Marvel — yes, a knockoff of a character that had just spent 10 years deflecting accusations of being a knockoff — to lead his own book. Anglo delivered the very-atomic-age-inflected Marvelman, in which an astrophysicist uses atomic energy to give young reporter Micky Moran the ability to transform into the superhero Marvelman whenever he says the word “KIMOTA.” That is, “atomic,” but backwards and with a K. There was even a “Marvelman, Jr.” or, Young Marvelman

For about a decade, Marvelman comics were a touchstone in the lives of UK kids, thanks in part to the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act of 1955, the nadir of the UK’s own anti-comics fervor. The Act limited American comics imports from reaching British shores for quite some time, allowing for the flourishing of locally sourced heroes like Marvelman. But that wouldn’t last forever.

In 1961, the American publisher Timely Comics began branding their Journey Into Mystery and Patsy Walker series as “Marvel Comics.” That moniker later extended to the company’s brand new hit, a superhero team comic called Fantastic Fourfrom a couple of guys named Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. The Marvel revolution was in motion.

By that time, anti-comics fervor had cooled in the US and the UK, and Marvel Comics reprints — handled by the company’s UK division, rather than being licensed to a local publisher— were immensely popular. Unable to compete with the American invasion, Miller & Son went bankrupt in 1963, and Marvelman went with them. But this was not the end of Captain Marvel or his imitators. Not by a long shot.

Marvel Super-Heroes #12, the debut issue of Captain Marvel (Mar-Vell).

Gene Colan, Frank Giacoia, Stan Goldberg, Artie Simek/Marvel Comics

In 1967, Marvel Comics, the rebranded name of Timely Comics, discovered that Fawcett Publications had allowed its trademark on the phrase “Captain Marvel” to lapse. 16 years after Captain Marvelceased production, Marvel Comics began printing a series under the same name, created by Stan Lee and Gene Colan, about the adventures of an alien whose given name was Mar-Vell. To the citizens of Earth, like air force security officer Carol Danvers would one day be, he was the superhero Captain Marvel.

Marvel exploited the key differences between a trademark and copyright. Trademarks are designed to cover words, phrases, graphics and other brand signifiers, while copyrights are designed to protect ownership of a piece of intellectual property — a story, character, song or other work. Trademarks have to be defended, sometimes zealously; the owner has to show that the trademark is in regular use and that it has not become genericized, or other businesses can defend their own right to use it.

Fawcett still held the copyright to Captain Marvel — his origin story, his costume, and his printed comics — but Marvel Comics now had the right to use “Captain Marvel” as branding. And two years after his debut, when sales were slumping, Roy Thomas and Gil Kane gave Marvel’s Captain Marvel a new gimmick, in which he became trapped in the Negative Zone. The only way for him to fight crime in our dimension was to swap places with a heroic kid in a red shirt and blue pants — mirroring Billy Batson’s subway origin story, but with perennial Avengers sidekick Rick Jones and space technology instead of magic.

The cute homage was also a deep cut; in 1969, only diehard comic readers would have remembered C.C. Beck’s Captain Marvel. There hadn’t been a new Captain Marvel story — at least, not one about a guy in a red suit who shouted “SHAZAM!” — in almost 20 years. And there would probably never have been one again, if not for DC Comics. In 1972, the comic giant licensed the character from Fawcett Publications, and began printing a series about a guy named Captain Marvel who wore a red suit and shouted “SHAZAM!”

Yes, the same company that had driven Fawcett out of the comic book business 21 years prior because Captain Marvel was similar to Superman went to its opponent and worked out a deal to print Captain Marvel comics. But DC’s license only covered the copyright, not the trademark, and this divergence of brand identity would define both Captain Marvels for nearly 40 years.

1972-2011: THE SECOND FEUD

DC’s first Captain Marvel series was called Shazam!, named so to avoid brushing up against Marvel Comics’ trademark of “Captain Marvel.” When DC editor Carmine Infantino gave the book the subtitle “The Original Captain Marvel,” Marvel sent a cease and desist letter to DC, to dispel any doubt about how prickly the competition was about to get. The book’s branding was changed to “The World’s Mightiest Mortal” for issue #15, but within the pages of Shazam!, Billy Batson still summoned a hero who went by the name “Captain Marvel.”

DC had an easier row to hoe than Marvel. They had the license to the copyright, and, in 1991, DC purchased the full rights to Captain Marvel and associated characters outright. Copyrights don’t need to be defended as assiduously as trademarks, and there were long periods between 1972 and 2011 during which Captain Marvel appeared only in backup stories of other books, as a member of a team, or not at all. His original creators struggled to gain an audience for the character in his classic incarnation, and he only really had one successful ongoing series, Jerry Ordway’s The Power of Shazam!, which ran from 1995 to 1999. (He also had a CBS TV series that ran from 1974 to 1976.)

From The Power of Shazam! (1994).

Jerry Ordway/DC Comics

Like Warner Bros.’ Shazam! film, DC creators (in a combination of work from Keith Giffen, J. M. DeMatteis, and Roy and Dan Thomas) made a slight but significant tweak to the character. From 1987 onward, Captain Marvel and Billy Batson were no longer two different people. Captain Marvel had reached the ultimate conclusion of Billy Batson’s original appeal as an audience surrogate: He was now literally a child in the body of an adult superhero.

In 1972, the moment DC Comics started publishing Shazam!, Marvel Comics editorial realized the situation: Given an inch, DC would eagerly yank back the trademark to their character’s name. If Marvel wanted to keep it, it would have to regularly publish a comic book called Captain Marvel, regardless of that book’s popularity, potentially forever. So that’s exactly what the company did.

Marvel’s first Captain Marvel series ended in 1979. In 1982, Marvel used the first book in its groundbreaking Marvel Graphic Novel line, Death of Captain Marvel, to showcase Mar-Vell’s tragic death from cancer. In 1985, the company reprinted a bunch of old Mar-Vell stories under the title Life of Captain Marvel. In 1989 and 1994, Marvel published one-shot stories about Mar-Vell’s first successor, Monica Rambeau (played by Akira Akbar in Marvel Studios’ Captain Marvel). In 1995 and 1997, Marvel published two short miniseries with the Captain Marvel name. In 2000, writer Peter David finally struck ongoing series gold for the first time in 20 years, with a Captain Marvel book about Genis-Vell, the son (sort of) of Mar-Vell, and his sister (sort of) Phyla-Vell, that ran for four years. In 2008, Marvel published another miniseries called Captain Marvel,about a shape-shifting Skrull sleeper agent who mistakenly believed himself to be Mar-Vell.

Captain Marvel’s England presence offers another even more complicated branch of this story. In 1982, a man by the name of Derek “Dez” Skinn, former editor in chief of Marvel’s UK division, obtained verbal permission from Mick Anglo — that’s the guy who created Marvelman, the knock off of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel — to make new Marvelman stories.

Skinn was looking for content for his putative black and white anthology comics series, Warrior, and thought that a modern relaunch of a UK cult classic would help sell copies. The black and white comics anthology series was a big staple of British comics in the era; and although not as famous 2000 AD, home of Judge Dread, Warrior’s 26 issues made a mark on comics history, not least for being the original publisher of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta.

From Moore’s Marvelman stories.

Alan Moore, Garry Leach/Warrior

Speaking of Moore, the young writer was the third person Skinn approached about a modernized Marvelman, and the first who showed the slightest interest in it. With Garry Leach and Alan Davis drawing, Moore wrote 21 story installments for Warrior, featuring an adult Micky Moran as an unhappy man who dreams of flying. Over the course of Moore’s story, Moran recovers his memories of being Marvelman, but also finds out that his cheerful adventures were a brain-washed delusion inflicted on him when he was a boy, by scientists attempting to use alien technology to place a nigh-all-powerful alien being under human control.

Moore’s dark, contemporary revival of the Golden Age Marvelman fiercely interrogated the very nature of the superhero myth, and, four years after he left Warrior, it was proof that he had the chops to tackle another project. Moore pitched Who Killed the Peacemaker?, a dark, contemporary revival of Charlton Comics’ Golden Age characters, to DC Comics. The company accepted, and the final series wound up with a different name: Watchmen.

Dez Skinn eventually licensed Moore’s Marvelman to American publisher Eclipse Comics, who began reprinting Moore’s work in the US in 1985. Except, just like DC Comics’ Captain Marvel, Eclipse could not call the book “Marvelman” without hearing from Marvel Comics’ lawyers. The entire series was renamed, colored, and its text relettered, to transform it into Miracleman.

Alan Moore’s Marvelman, now Miracleman.

Alan Moore, Garry Leach/Eclipse Comics

Under Eclipse, Moore continued writing his story — begun as Marvelman, now called Miracleman — and in 1988, was succeeded in writing duties by Neil Gaiman, who wrote the series until 1994, when Eclipse went bankrupt. In 1996, Eclipse’s assets, including Miracleman, were purchased by Spawn-creator and entrepreneur Todd McFarlane, and it was this purchase that embroiled the series in another of the comics world’s great intellectual property ownership battles.

Gaiman held that McFarlane had improperly compensated him for the co-creation of three Spawncharacters, and sued McFarlane for the rights to those characters and Miracleman in 2002. All profits from Gaiman’s 2003 Marvel Comics miniseries, Marvel 1602, went directly to Marvels and Miracles, an LLC Gaiman had formed for the purpose of sorting out who actually held the rights to Marvelman/Miracleman. After a court settled in Gaiman’s favor, Marvel Comics purchased the rights to Marvelman from Mick Anglo, in a much more legally binding way than Dez Skinn’s gentleman’s agreement.

So, in 2014, Marvel Comics began publishing reprint editions of Miracleman, a reprinted form of Marvelman (renamed out of fear of Marvel Comics’ lawyers), which was a modern revamp of the Golden Age Marvelman, which was an open knockoff of Captain Marvel, a character who belonged to DC Comics (after that same company used a lawsuit to bar his publication for 20 years), but whose name belonged to Marvel Comics, who had engaged in a Captain Marvel trademark/copyright cold war with DC for 40 years. Where does it all end?

2011-NOW: ENTER CAROL DANVERS

In 2011, DC Comics kicked off its first line-wide continuity reboot in over 25 years, an era known as the New 52. Captain Marvel came along, except … nobody was calling him Captain Marvel anymore. When Billy Batson and family appeared in backup stories to the New 52’s Justice League, the character’s name was simply “Shazam.”

In 2012, writer Geoff Johns told Newsarama that the name change was for multiple reasons, but “one is that everybody thinks he’s called Shazam already, outside of comics ... you know, every comic book he’s in right now has Shazam on the cover.”

Right around the time that Captain Marvel finally, officially, became Shazam, Marvel Comics struck Captain Marvel gold. Kelly Sue DeConnick and Dexter Soy introduced Carol Danvers — formerly the superhero Ms. Marvel, formerly a supporting character in Marvel’s first Captain Marvel series — the newest character to wear the boots of Captain Marvel, and her series was a runaway hit. In 2014, Marvel Studios announced that it had a Captain Marvel movie in production, though delays would bump it from an original July 6, 2018 release date.

In 2017, Warner Bros. announced that David F. Sandberg would be directing Shazam!, rescuing a project that had been in development long enough to be referred to as a “Captain Marvel movie.” Later in 2017, Marvel Comics announced that Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham would return to Miracleman to complete their final, interrupted arc once and for all.

On March 8, 2019, Captain Marvel hit theaters. On April 5, 2019, Shazam! will, too.

Superman and Shazam (then still called Captain Marvel) in 2005’s Superman/Shazam! First Thunder.

Judd Winick, Joshua Middleton/DC Comics

Superhero intellectual property battles didn’t start with Marvel Studios, Sony Pictures, and 20th Century Fox. The American comics industry was built on epic battles — over intellectual property.

Since the earliest days of comics, the largest publishers have ensured that artists had next to no ownership of their creations. That standard has only just begun to change in the past 30 years. Inventing intellectual property on a work-for-hire basis is simultaneously American comics’ greatest hurdle and, shamefully, a source of one of its greatest strengths.

The work-for-hire model has left creator after creator in the dust, especially now that characters like Rocket Raccoon, Venom, and Aquaman are billion-dollar properties. And yet, in superhero comics, passing a character from artist to artist and writer to writer is not just the primary way their stories survive, but the primary way they evolve. This is how superheroes have remained relevant for four generations of readers and counting.

the extreme of the ’90s. By this time, he wasn’t a character who was failing to evolve — he was a character who stood in interesting contrast to his peers. He was a welcoming throwback; nostalgia for a lost and perhaps nobler era.

In contrast, Marvel Comics’ endless churn of new revamps — Captain Marvel is an alien man! No, a human woman with energy powers! No, a genetically engineered alien! No, his sister; a skrull; his worst enemy! — still took 40 years and half a dozen completely different incarnations to find a hit character in Captain Marvel.

The confusion from all of this still lingers. Today, Shazam’s Wikipedia article is still titled “Captain Marvel (DC Comics),” while you’ll find Marvel’s original Captain Marvel under “Captain Marvel (Mar-Vell).” Today, Carol Danvers is inarguably the most famous Captain Marvel. On Wikipedia’s “Captain Marvel (disambiguation)” page, she is listed not first, not second, or third, but 12th.

But we’ve reached a new section of the timeline. As they’ve done for B-list Marvel characters and iterations of Batman, Captain Marvel and Shazam! will mainstream two characters with entangled history and clear up 80 years of behind-the-scenes drama.

And the next time you shake your head at a superhero’s complicated backstory, just remember: It was probably even more complicated in real life.