You are Not Lazy or Undisciplined. You Have Internal Resistance.

Why you can’t just do it, and what to do instead

When I was writing my PhD I didn’t have bad weeks. I had bad months. The kind when each day you wake up thinking, “Today I will actually do the thing” and then you… don’t. Somehow the day ticks by and then it’s 11 pm and you still haven’t done the thing and it feels like you might as well go to bed and start over tomorrow, but already you have a sinking horrible sense that you won’t do it then either. And lo, the cycle repeats.

It doesn’t have to be a PhD, of course. This why-can’t-I-just-do-it circle of hell can happen any time you’re trying to do something you care about that is big and in some way new. And once the cycle really gets going, you can find yourself prey to self-loathing so corrosive and debilitating that I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

Which makes sense. Why wouldn’t you feel self-loathing when every day you violate a promise you made to yourself about something important to you AND you don’t know why AND you can’t stop AND you have no one else to blame because YOU ARE DOING IT ALL TO YOURSELF for some mysterious fucking reason you don’t even understand?

As far as most of our culture is concerned, the answer to this torturous cycle of not-doing-the-thing also lies in what’s wrong with us, more or less: we’re lazy, we’re unproductive, we’re irresponsible, we’ve let ourselves become addicted to our phones, we’re procrastinators, we’re not meditating, blah blah blah. In the coaching world, it’s our ‘lizard brain’ holding us back from the human evolution that is our birthright. Basically whatever is keeping us from doing the thing is something that’s wrong with us or our behaviour, something that needs to be controlled, eradicated, tamed, left behind or put in its place.

In 15 years of helping people over these kind of blocks, not to mention a life-time of getting over them myself, I have become 100% certain of two things: that way of thinking about the problem is not accurate, and it’s definitely not fucking useful.

You are not lazy. You are not undisciplined. You are not irresponsible. You are not suffering from mysterious ‘Just Can’t Do It’-itis.

You are experiencing internal resistance. And internal resistance is not a flaw, nor is it all powerful. It is a facet of human creativity and growth, and it can be managed. But we have to start by recognizing it for what it is.

What is internal resistance?

In his book The War of Art, writer Steven Pressfield names the force that keeps us from using our talents “the Resistance”. The Resistance is a mysterious hostile force, an enemy that has to be bested. In Pressfield’s imagery, we spend each day fighting back the resistance in an eternal battle that is as timeless as it is endless.

Pressfield’s model has helped a lot of people, including me. But I think ultimately he’s only about half right. Yes, resistance is intrinsic to using your talents, and it has to be faced daily. But it is not a grim otherworldly force that blights our existence. And treating it as an external enemy to be battled is both a losing endeavour and a lost opportunity. (We could also talk about the machismo involved in his approach, but that’s a subject for another post.)

Internal resistance is not a free-standing inherently malevolent tendency of the universe. It’s not the freaking Dark Side! It’s a part of us, and it is grows from the exact same soil as every talent and skill and goal we have: our brains, our personal history, our families and our culture.

Because that soil is unique to each of us, every person’s internal resistance has its own particular causes and flavours and effects. But what every experience of internal resistance shares is a prediction and fear of pain.

Internal resistance is an attempt to avoid the pain we associate with successfully doing the thing.

The causes of this pain are as individual as we are, but in my experience it is usually tied to some kind of predicted loss of love and connection, whether it’s love from others or for ourselves. Which makes sense: what else would be universally terrifying enough that we would block our own talents and goals to avoid it?

What can you do with your internal resistance?

If you think about internal resistance this way, I think it becomes clear why approaching it through ideas of laziness or lack of discipline is so unhelpful. Internal resistance is not lazy — it’s fucking energetic as hell! It takes a lot of work to push back on our desire to move toward our goal, day after day.

And if we try to use discipline to increase our movement toward the goal, we wind up with another version of the same problem, because we ultimately increase the resistance: the more likely it looks like we’re going to make it to the finish line, the greater the fear and the stronger the resistance.

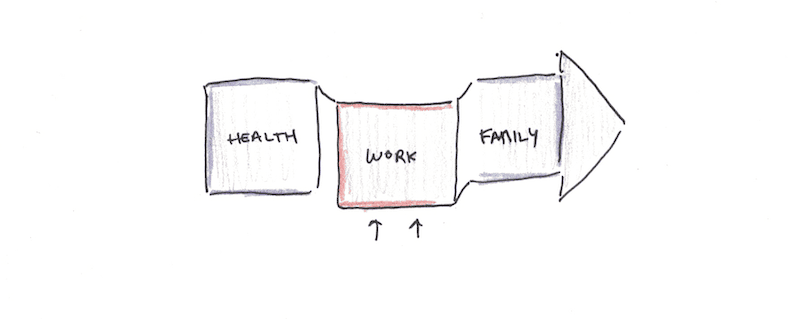

Basically, we’re already locked in a mental tug of war, and trying to apply discipline just means both sides pull harder.

So what can we do instead?

Here are some places to start:

1. Recognize that internal resistance is on your side. Part of what is so awful about the cycle-of-not-doing-the-thing is that it feels so self-destructive. But internal resistance does not want to destroy us; it literally wants the opposite! It only exists to protect us from pain.

You are not being self-destructive. You just have two deeply rooted and fundamentally contradictory ideas about what is best for you: doing the thing, and not doing the thing.

2. Get curious about this pain that your brain is so worried about. When we understand exactly what pain we fear and why, we can work on reducing those fears. This is why I think treating resistance as an opaque external force is such a mistake. Internal resistance is not immovable — it responds to reason, to alternative scenarios, to making space for the emotions that seem like such a threat — but to shift it you have to understand its particular content for you.

3. Negotiate. You may not be able to figure out what is motivating your internal resistance immediately, and even once you do, it can take some time to figure out how to address your fears and worries about pain in the offing. In the meantime, I suggest haggling. Will your internal resistance allow you to work for 10 minutes? What about five? If you can’t work formally, could you talk into your phone? How about brainstorming in the bathtub?

You can create so much increased space in your brain just moving from “I need to apply will power so I stop being so bad and lazy” to “I’m experiencing a lot of internal resistance, let me get inventive in working with it today”.

4. Recognize that you are not alone in this. Even if resistance is not a superhuman force, I think Pressfield is right to envision it as something that besets most of us. Yes, there are rare people who do not — or at least don’t seem to — experience much internal resistance, who seem to just produce and produce. But I am willing to bet that you also seem like that kind of person to someone in your life.

Listening to your resistance

There’s another reason why I think we should treat internal resistance as a form of wisdom rather than a malevolent opponent. It holds a lot of knowledge about what we secretly believe we might be able to do. As in: your brain wouldn’t be so afraid of the costs of you doing the thing if it thought you were going to do something forgettable and inconsequential.

Likewise, it can be helpful to remember that the force of your internal resistance is also a measure of how much you actually want to do the work, no matter how many days you don’t quite manage to get there. The only reason the tug of war isn’t over — the only reason every day feels so fraught— is because you’re still pulling toward your goal, because you’ve got your heels dug in.

Right now, it’s exhausting and sad because it feels like whichever side wins, part of you will lose. But that’s why we work to understand the internal resistance. When we do, we can stop the tug of war and start dealing with the emotional landmines that a part of us is so certain lie ahead. Sometimes the fears turn out to be imaginary, and sometimes the pain is very real. But either way, they become just one part of the experience of doing the thing we want to do, rather than a barrier to doing it in the first place.

https://medium.com/ counterarts/you-are-not-lazy-or-undisciplined-you-are-experiencing-internal-resistance-755a02673aa9

Why you can’t just do it, and what to do instead

When I was writing my PhD I didn’t have bad weeks. I had bad months. The kind when each day you wake up thinking, “Today I will actually do the thing” and then you… don’t. Somehow the day ticks by and then it’s 11 pm and you still haven’t done the thing and it feels like you might as well go to bed and start over tomorrow, but already you have a sinking horrible sense that you won’t do it then either. And lo, the cycle repeats.

It doesn’t have to be a PhD, of course. This why-can’t-I-just-do-it circle of hell can happen any time you’re trying to do something you care about that is big and in some way new. And once the cycle really gets going, you can find yourself prey to self-loathing so corrosive and debilitating that I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

Which makes sense. Why wouldn’t you feel self-loathing when every day you violate a promise you made to yourself about something important to you AND you don’t know why AND you can’t stop AND you have no one else to blame because YOU ARE DOING IT ALL TO YOURSELF for some mysterious fucking reason you don’t even understand?

As far as most of our culture is concerned, the answer to this torturous cycle of not-doing-the-thing also lies in what’s wrong with us, more or less: we’re lazy, we’re unproductive, we’re irresponsible, we’ve let ourselves become addicted to our phones, we’re procrastinators, we’re not meditating, blah blah blah. In the coaching world, it’s our ‘lizard brain’ holding us back from the human evolution that is our birthright. Basically whatever is keeping us from doing the thing is something that’s wrong with us or our behaviour, something that needs to be controlled, eradicated, tamed, left behind or put in its place.

In 15 years of helping people over these kind of blocks, not to mention a life-time of getting over them myself, I have become 100% certain of two things: that way of thinking about the problem is not accurate, and it’s definitely not fucking useful.

You are not lazy. You are not undisciplined. You are not irresponsible. You are not suffering from mysterious ‘Just Can’t Do It’-itis.

You are experiencing internal resistance. And internal resistance is not a flaw, nor is it all powerful. It is a facet of human creativity and growth, and it can be managed. But we have to start by recognizing it for what it is.

What is internal resistance?

In his book The War of Art, writer Steven Pressfield names the force that keeps us from using our talents “the Resistance”. The Resistance is a mysterious hostile force, an enemy that has to be bested. In Pressfield’s imagery, we spend each day fighting back the resistance in an eternal battle that is as timeless as it is endless.

Pressfield’s model has helped a lot of people, including me. But I think ultimately he’s only about half right. Yes, resistance is intrinsic to using your talents, and it has to be faced daily. But it is not a grim otherworldly force that blights our existence. And treating it as an external enemy to be battled is both a losing endeavour and a lost opportunity. (We could also talk about the machismo involved in his approach, but that’s a subject for another post.)

Internal resistance is not a free-standing inherently malevolent tendency of the universe. It’s not the freaking Dark Side! It’s a part of us, and it is grows from the exact same soil as every talent and skill and goal we have: our brains, our personal history, our families and our culture.

Because that soil is unique to each of us, every person’s internal resistance has its own particular causes and flavours and effects. But what every experience of internal resistance shares is a prediction and fear of pain.

Internal resistance is an attempt to avoid the pain we associate with successfully doing the thing.

The causes of this pain are as individual as we are, but in my experience it is usually tied to some kind of predicted loss of love and connection, whether it’s love from others or for ourselves. Which makes sense: what else would be universally terrifying enough that we would block our own talents and goals to avoid it?

What can you do with your internal resistance?

If you think about internal resistance this way, I think it becomes clear why approaching it through ideas of laziness or lack of discipline is so unhelpful. Internal resistance is not lazy — it’s fucking energetic as hell! It takes a lot of work to push back on our desire to move toward our goal, day after day.

And if we try to use discipline to increase our movement toward the goal, we wind up with another version of the same problem, because we ultimately increase the resistance: the more likely it looks like we’re going to make it to the finish line, the greater the fear and the stronger the resistance.

Basically, we’re already locked in a mental tug of war, and trying to apply discipline just means both sides pull harder.

So what can we do instead?

Here are some places to start:

1. Recognize that internal resistance is on your side. Part of what is so awful about the cycle-of-not-doing-the-thing is that it feels so self-destructive. But internal resistance does not want to destroy us; it literally wants the opposite! It only exists to protect us from pain.

You are not being self-destructive. You just have two deeply rooted and fundamentally contradictory ideas about what is best for you: doing the thing, and not doing the thing.

2. Get curious about this pain that your brain is so worried about. When we understand exactly what pain we fear and why, we can work on reducing those fears. This is why I think treating resistance as an opaque external force is such a mistake. Internal resistance is not immovable — it responds to reason, to alternative scenarios, to making space for the emotions that seem like such a threat — but to shift it you have to understand its particular content for you.

3. Negotiate. You may not be able to figure out what is motivating your internal resistance immediately, and even once you do, it can take some time to figure out how to address your fears and worries about pain in the offing. In the meantime, I suggest haggling. Will your internal resistance allow you to work for 10 minutes? What about five? If you can’t work formally, could you talk into your phone? How about brainstorming in the bathtub?

You can create so much increased space in your brain just moving from “I need to apply will power so I stop being so bad and lazy” to “I’m experiencing a lot of internal resistance, let me get inventive in working with it today”.

4. Recognize that you are not alone in this. Even if resistance is not a superhuman force, I think Pressfield is right to envision it as something that besets most of us. Yes, there are rare people who do not — or at least don’t seem to — experience much internal resistance, who seem to just produce and produce. But I am willing to bet that you also seem like that kind of person to someone in your life.

Listening to your resistance

There’s another reason why I think we should treat internal resistance as a form of wisdom rather than a malevolent opponent. It holds a lot of knowledge about what we secretly believe we might be able to do. As in: your brain wouldn’t be so afraid of the costs of you doing the thing if it thought you were going to do something forgettable and inconsequential.

Likewise, it can be helpful to remember that the force of your internal resistance is also a measure of how much you actually want to do the work, no matter how many days you don’t quite manage to get there. The only reason the tug of war isn’t over — the only reason every day feels so fraught— is because you’re still pulling toward your goal, because you’ve got your heels dug in.

Right now, it’s exhausting and sad because it feels like whichever side wins, part of you will lose. But that’s why we work to understand the internal resistance. When we do, we can stop the tug of war and start dealing with the emotional landmines that a part of us is so certain lie ahead. Sometimes the fears turn out to be imaginary, and sometimes the pain is very real. But either way, they become just one part of the experience of doing the thing we want to do, rather than a barrier to doing it in the first place.

https://medium.com/ counterarts/you-are-not-lazy-or-undisciplined-you-are-experiencing-internal-resistance-755a02673aa9