Its good to look back and see this slow burn in action!!

THE POLICE STATE IN REVIEW, 2013

While some would have you believe the biggest stories of 2013 were about twerking celebrities and over-hyped real-life courtroom sagas, much bigger events were happening with far more lasting national significance. The foundation of an American police state is already laid and coming into full bloom, while most of the country remains blissfully focused on sports, reality shows, establishment pseudo-news, and other distractions.

While all of the injustices that took place in 2013 would require an encyclopedia to cover adequately, this list is designed to illustrate certain trends and significant stories from the past year. If Americans don’t fix their apathy and disengagement toward causes that matter, we can expect these trends to continue toward their logical conclusions: an increasingly repressive police state dominating the lives people inside these borders and beyond.

CHECKPOINTS, WARRANTLESS SEARCHES BECOME A WAY OF LIFE

(Source: AP/The Sacramento Bee, Randall Benton)

The state of the 4th amendment is in truly bad shape, given the prevalence of warrantless checkpoints and warrantless bag searches being used all around the country for various reasons. No longer restricted to airport terminals, the unconstitutional tactics are now being used in subways, bus stations, on bridges, at parades, and anywhere else the government can get away with them. This is facilitated by the palpable fear of terrorism and with financial incentives from the federal government.

In what was dubbed “Operation Independence,” the federal government along with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department staged a high-visibility terror drill in the LA subway this July. Deputies dressed in paramilitary garbteamed up with agents from the TSA and DHS to require travelers to open up their bags and prove their innocence before being allowed to commute. These tactics have sadly become commonplace in many major cities.

Security measures at major events have gotten increasingly invasive. At the annual ‘Mackinac Bridge Walk’ in St. Ignace, Michigan, up to 40,000 walkers were subjected to warrantless bag searches in the interest of event security. In Chicago, warrantless bag searches were performed on public sidewalks during a celebratory parade for the Blackhawks’ hockey championship, and were again performed along the 26-mile track of the Chicago Marathon. A famous parade in Pasadena, California, is used as an excuse to search the interiors of hundreds of vehicles who wish to park on public streets.

The “stop and frisk” phenomenon was alive and well in 2013. The appalling practice involves police stopping pedestrians, usually pushing them up against a wall and then patting them down, searching their pockets, and opening up their purses and bags. The practice has been notorious in New York City, which not only has aggressive enforcement on the streets but also allows cops to roam around inside private apartment buildings and search tenants. Stop and frisk is also work in Philadelphia, Detroit, northwest Indiana, and other areas.

Sobriety checkpoints have been around a long time, but are increasing in offensiveness. Checks for sobriety have turned into opportunities to search people’s vehicles. People are sometimes being forced off the roads into parking lots and sniffed with dogs in order to be permitted to continue driving down public streets. Some sobriety checkpoints are being dubbed “no refusal” because anyone who refuses to prove their innocence through a breath test will be strapped down to a table and have their blood forcibly taken from them. New saliva swab analyzers now allows police to detect and arrest people based on on them having things like marijuana and prescription drugs in their systems while driving.

Not to be outdone by local cops, the federal government is setting up checkpoints in reportedly 60 communities to take blood and saliva samples from drivers in a multi-million dollar “survey.”

The reasons for warrantless searches is only limited by the imaginations of the police. There are now regular license and vehicle inspection checkpoints, fruit possession checkpoints, firework possession checkpoints, tampon possession searches, searches for canned beverages, roadside smog checkpoints, and more.

DOD PROGRAM 1033 MILITARIZING LOCAL POLICE DEPARTMENTS

MRAP vehicles

Those who are paying attention are seeing the constant notices of military equipment from overseas war-zones being dispersed to domestic police departments. These giveaways are usually in the form of armored vehicles (as far as the public knows). This is all made possible by the Defense Department’s Program 1033. In place since 1997, the program allows the DOD to give away the equipment — often free of charge — to local police departments who apply for the equipment grants.

This year has been the year of the MRAP, or Mine Resistant Armor Protected vehicle. For the first time these fighting vehicles, costing an upwards of $600,000 each, are being sent out to American cops, and in rapid fashion. The hulking trucks, which come with armor plating, gun ports, bullet-proof glass, and a gun turret on top, end up being used on SWAT raids in residential America.

The program dispersed more than half a billion dollars worth of equipment in 2012, and 2013 is expected to keep that pace, if not exceed it. There is no oversight over Program 1033 and the Department of Defense has never been audited, meaning there is overwhelming room for fraud and abuse. The U.S. taxpayers have been burdened with purchasing this equipment and now it is being given away without compensation; without auction. And no one really knows the full scope of the project.

One does not have to look far for examples of local departments becoming militarized. MRAP acquisitions have taken place in every state, the latest including Alabama, Indiana, Texas, Idaho, California, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois, and Nevada.

To understand the implications of what a militarized police force is capable of, consider the extravagant anti-terror drill performed by LAPD this year at the National Homeland Security Association’s conference in June. Gunfire echoed through downtown Los Angeles, bombs exploded, and helicopters swooped low among tall office buildings in a demonstrated response to two terrorists in a pickup truck. Paramilitary police pulled up in a bomb-dropping armored vehicle, and engaged in a mock firefight. Guests from around the nation and world attended the conference to marvel at militarized law enforcement in action. The performance was funded by the federal government and was designed to inspire more departments to become militarized.

THE TSA CONTINUES TO EXPAND ITS REACH

The Transportation Security Administration had another year characterized by abuse, theft, and violations of civil rights. There was a steady stream of children being tormented, property being stolen, and genitals being grabbedthis year, as usual. Americans are being searched without probable cause or warrants while being threatened with arrest over loudspeakers if they talk back to the checkpoint agents. There are too many of these stories to count and this behavior has been standard operating procedure since the TSA was created. Some of the agency’s recent advancements deserve to be mentioned, however.

Checkpoints are now involving a much deeper look into traveler’s private personal information. Nothing short of a criminal background check will allow a person to fly in America anymore. The new security program involves gaining access to travelers’ private employment information, vehicle registrations, travel history, property ownership records, physical characteristics, tax identification numbers, past travel itineraries, law enforcement information, “intelligence” information, passport numbers, frequent flier information, and other “identifiers” linked to DHS databases. The TSA is allowing people to purchase the title of “trusted traveler” if they willingly submit their biometric fingerprint scans into a FBI database, submit to a criminal background check, and pay the TSA a fee of $85.00 for a five-year PreCheck membership.

The TSA has evidently expanded its reach to parking lots this year, after encouraging and overseeing airport security plans that involve opening up parked cars and performing warrantless searches on their interiors. Although the TSA may not be directly involved with performing these searches, they are approved by the TSA and some airports claim they are mandated by the TSA.

The response of may Americans is to avoid the TSA by ceasing air travel. This is a shortsighted solution, as the TSA has never been bound to airports. As one TSA official pointed out, “We are not the Airport Security Administration.” Indeed, avoiding the TSA became more challenging in 2013, and is bound to become more difficult in the future.

TSA agents are not making regular appearances on other modes of transportation. Special armed TSA units — known as VIPR teams — are showing up at public venues, sporting events, train terminals, music festivals, rodeos, highway weigh stations in order to “surprise” the terrorists with “suspicionless” searches. “The security at airports has increased so the bad guys are now traveling on the trains and buses,” said TSA agent George Robinson at a surprise TSA “Spot Checks” at an Austin railway. The TSA was active in and around the Superbowl this year, one of many places many never expected to see the TSA operating.

To soften their villainous image, the TSA has been spending taxpayer money to produce cartoons designed to propagandize children into accepting warrantless checkpoints. Getting searched by strangers in uniformed is presented as fun and exciting — and vital to safety.

THE SURVEILLANCE STATE, REVEALED

(Warner Brothers)

This year we experienced a lot of mainstream discussion about the breadth of the Federal Government’s domestic surveillance grid, in large part due to the revelations from NSA contractor-gone-rogue, Edward Snowden. Snowden discovered over the course of his employment with the NSA that the American public was completely unaware of the extent of spying being performed by the government on its own people, and felt compelled to go public. In June, Snowden went to journalist Glenn Greenwald with up to 200,000 NSA documents to prove what the government was up to. Greenwald has since released a series of damning articles exposing the NSA spy grid, which have received international attention.

Now officially charged by the U.S. government with espionage, Snowden has been in hiding overseas for over 6 months. But his leaks have provided valuable insight into the operation of the government. Its a bit ironic that the man exposing the spy program is labeled the spy, but I digress.

Greenwald’s articles have revealed that the NSA’s modus operandi is to “collect it all,” meaning every collectible form of communication or data. To this end, the NSA has been utilizing what it calls the Prism program, under which the agency has obtained direct access to the systems of Google, Facebook, Apple and other US internet giants. With this access to internet traffic, the NSA uses a program called XKeyscore, which is surveillance tool that collects “nearly everything a user does on the internet.” One presentation of XKeyscore claims the program collects the content of emails, websites visited and searches, as well as their metadata.

“I, sitting at my desk,” Snowden said, could “wiretap anyone, from you or your accountant, to a federal judge or even the president, if I had a personal email”.

Another recent leak revealed that the NSA is “getting vast volumes” of records of individual’s physical locations from their cell phones — faster than it can process and store — as the agency surveils the nation’s mobile phone networks. It goes deeper than that though. Greenwald reported that the NSA is collecting information about phone calls from millions of Americans daily. Such information includes the numbers of both parties on the call, their locations, the time, and the duration of all calls made on the network.

BORDER SECURITY AS OPPRESSIVE AS EVER

Vehicles are searched indiscriminately at a border checkpoint. (Source: Eric Gay/AP Photo)

A constant barrage of stories of abuse from U.S. Customs and Border Patrol have arisen in 2013. These did not only occur at the physical borders, but at the numerous domestic checkpoints that appear all over U.S. roadways across the southwest. Up to 100 miles into the country, permanent roadblocks exist where travelers are asked by federal agents to prove their citizenship and often subjected to searches and other harassment.

At one such internal checkpoint in California, a man named Robert Trudell decided he was going to remain silent in his car until the agents let him continue traveling down the roadway. As he calmly sat in his car and photographed the scene, agents bashed in his window with a club and extracted him from his car. Police State USA has viewed numerous other videos of harassment at border patrol checkpoints, and find their prominent existence on U.S. highways to be very disconcerting.

Earlier this year, the official watchdog over civil rights for the Department of Homeland Security gave the green light for “suspicionless” seizure of any electronics they encounter from travelers crossing the border. Thousands of laptops, cell phones, and other personal property has been confiscated by customs agents, forcing the owner to spend lots of time and money to attempt to reclaim the items — not to mention the loss of privacy suffered by the owners.

Border Patrol and DHS has taken an interest in harassing small aircraft pilots as well, as we have seen multiple such stories this year. Reports follow a pattern: CBP agents approach pilots, request aviation paperwork, and conduct an extensive searches of their aircraft, often including removal of all contents. Agents have been tight-lipped about the reason or justification for these warrantless searches. Taking the harassment up a notch, DHS ordered one hobbyist glider pilot named Robin Fleming to the ground for a search. He says he was threatened with being shot down from the sky.

THE DESTRUCTIVE DRUG WAR WAGES ON

DEA agents (Source: Mark Wilson/AP Photo)

The War on Drugs has been the source of incomprehensible levels of injustice, government corruption, brutality, and abuse for decades in the United States. Although year 2013 represents no marked difference from the status quo, these Drug War abuses constitute far too great a threat to go unmentioned in this list.

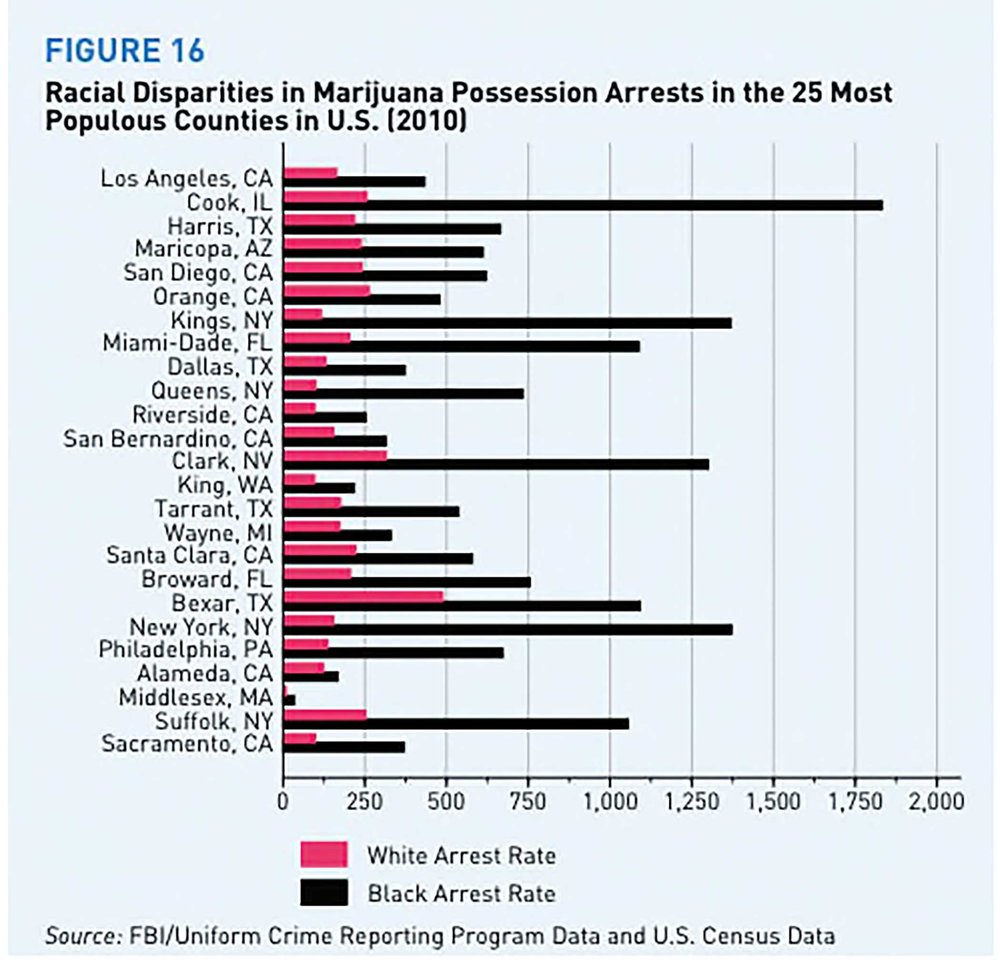

We saw countless people imprisoned for non-violent, victimless crimes. I say countless because the numbers are truly unknown when considering all of the federal, state, county, and city-level jails housing inmates for drugs. What we do know is that there 1,571,013 prisoners in state and federal prisons in 2012, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Of the federal inmates, around half of the prisoners are being locked up because of the War on Drugs. The number of lives ruined in the name of prohibition cannot possibly be tallied. Many are going to prison for decades — even life imprisonment — without ever having committed a violent offense. One such example was the case of Jerry Duval, a farmer who was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison for growing marijuana for medicinal use in the manner he was licensed to in the state of Michigan.

The Drug War gives the government the perfect vehicle for expanding its ability to legally steal from citizens, and this year has been no exception. Thanks to a legal maneuver known as Civil Asset Forfeiture, government agents can confiscate property and cash from anyone that they merely “suspect” of being involved in the drug trade. Thanks to recent advancements in domestic spying capabilities, the DEA has managed to double its amount of seizures since 2001. The owners of the seized property don’t even have to be charged with a crime, but often have to spend a small fortune in court to prove their innocence and get their possessions back. This practice varies across the country, but the prospect of keeping seized property provides a direct incentive for confiscation in any agency where it is used. For Darren Kent, a disabled widower in New Jersey, Drug War forfeiture could allow police to confiscate his house, his bank account, his 2 vehicles, and other property — all because of illegal plants he allegedly grew in his basement.

The enforcement of these silly drug laws has become increasingly aggressive and brutal. When someone is suspected of committing a non-violent drug offense, there is often a team of masked, paramilitary SWAT agents sent in the middle of the night to break down the doors and windows of their home, hold the occupants at gunpoint, and shoot any family pets that dare to challenge their presence. As one could imagine, this insane policy of “no-knock raids” over drugs leads to an unending torrent of violence and bloodshed inside people’s homes. In 2013, Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputies gunned down 80-year-old Eugene Mallory in his bed during a legal home-invasion to investigate if he was making meth. Earlier this month, police negligently shot Krystal Barrows, mother of three, in the head during a drug raid in Chillicothe, Ohio.

In case its not obvious, prohibition laws leave open the legal doorways for many innocent people to feel the brunt of the police state. In 2013, a family of maple syrup farmers in Illinois was raided on suspicion of making meth. TheHarte family of Kansas says that after buying hydroponics equipment for their indoor garden, police stormed their house in a manner that reminded them of Navy SEALs storming the bin Laden residence. Urban garden advocate John Kohler, of GrowingYourGreens.com, had his home searched because police thought he might be growing illegal plants in his house. One does not have to look far for more examples of drug raids gone bad.

Not even the elderly can escape from the harassment of strident drug enforcers have. Tennessee police pulled over and harassed an elderly couple because their car had a Ohio State University bumper sticker that the police officer thought might represent a marijuana leaf. A Utah man’s final moments with his recently-deceased wife were rudely interrupted when police barged into his home to confiscate her prescription painkillers.

It should be obvious that drug prohibition gives perverts and sexual predators a convenient place to legally abuse citizens while getting paid to do so. In June, a story broke about a female driver being asked to lift her shirt and shake her bra multiple times for a police officer who wanted her to prove she didn’t have drugs packed in it. In Texas, two bikini-clad women were given cavity searches on the side of the highway. “You’re going to go up my private parts?” Brandy Hamilton asked the officer. “Yes, ma’am,” the officer responded, before jamming a finger into each of their crotches with the same glove.

These forced cavity searches were a regular occurrence in 2013, in what can only be described as cases of legal rape. After rolling a stop sign, David Eckert of Deming, Utah, was detained and taken to a hospital, and for hours he was subjected to manual finger probes of his anus, forced to take an enema and defecate in front of police officers, forcibly X-rayed, and ultimately given a full-blown colonoscopy to attempt to find drugs in his colon. And this case is not unique. An American woman returning to the United States from Mexico was detained at the border near El Paso, chained to a hospital bed and given a forcible gynecological exam, involving finger penetration, forced defecation, and X-rays and a CT-scan. A 26-year-old Oregon man named Jason Barnes was forcibly catheterized by police after he was stopped by police for riding a bicycle without lights.

Stories from 2013 also should have made it glaringly obvious how easy it is to wrongly convict people and ruin innocent lives. In February, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that “a court can presume” an alert by a drug-sniffing dog provides probable cause for a search, even if the dot is not fully trained and lacks any documentation of its accuracy record. If animals deciding your fate is not disconcerting enough, consider what happens when the government agents decide to say you possessed contraband when you actually didn’t. Tens of thousands of drug cases may have been corrupted by a Massachusetts crime-lab chemist named Annie Dookhanwho collaborated with prosecutors to achieve more convictions. A Georgia judge ordered police officers to frame a woman with drugs after she refused to have sex with him. The potential for abusing “possession” laws are endless.

SCHOOLS GROOM CHILDREN FOR LIFE IN POLICE STATE USA

(Source: Yuma Sun / AP)

Government schools have always been the source of indoctrination and inadequate education, but the rise of security hysteria and zero-tolerance policies has made them into veritable conditioning centers for life in the American police state.

As a matter of policy in most compulsory government schools, students are subjected to warrantless searches of their bags and lockers, dog sniffs, and are even being forced to give urine samples without probable cause. Drug enforcement and education takes on a variety of different forms. In Indiana, police officers subjected a class of 5th graders to a “simulated drug raid” in a “drug awareness” event that resulted in one student getting attacked by the police dog that was demonstrating how it might children for drugs if the police were crashing a party at someone’s home.

With modern technology, they are being watched and listened under sophisticated surveillance systems, sometimes which are fed directly to police departments. Some schools are making students are having to carry RFID badges or use biometric scanners to track attendance and movement. Their bodies are forced to endure mass-medication at earlier and earlier ages.

Many schools use what have been known as “isolation booths” for children who misbehave, which in practice are tantamount to solitary confinement in a dark closet.

Parking lots are subject to warrantless searches; some so draconian that high school students are getting felonies for leaving pocket knives locked in their cars. In fact, it is common to have police officers regularly in school so administrators can outsource discipline to courts and jails. An undercover cop disguised as a high-schooler in Temecula, California, befriended an autistic boy and convinced him to purchase marijuana in order to arrest him.

The curriculum is unsurprisingly pro-statism, with recent (and glaring) examples involving students being asked to justify repealing amendments out of the Bill of Rights and being taught that government is like “family” and should be obeyed.

In addition, schools are being locked down at every possible opportunity. A school in Idaho went into “full prison mode” when a student brought a folding shovel. A Long Island school went into lockdown when a child had a lime green Nerf toy.

The lockdowns are becoming so routine that police departments and schools are running terror drills to make sure they run smoothly. The El Paso SWAT team staged a “surprise” terror drill in a school in which police charged into the school, used simulated gunfire, and detonated concussion grenades while they took over the school — to the surprise of everyone except for the principal. A similar terror drill was conducted in a Chicago school “in an effort to provide our teachers and students some familiarity with the sound of gunfire.” An Oregon school hired a man to wear a mask and carry a realistic gun into a faculty meeting and surprise teachers with realistic sounding gunfire in order to test their “readiness.” In Ohio, a mock hijacking was staged on a school bus containing children so that the SWAT team could practice its explosive rescue techniques.

MORE DANGEROUS DECISIONS FROM THE SUPREME COURT

The Supreme Court

SCOTUS made a few rulings in 2013 regarding the police state. While certainly not the worst court decisions we’ve endured, they can be added to a long list of bad ones.

In Salinas v. Texas, the court ruled 5-4 that when a suspect doesn’t answer a question during an interrogation, his silence can be used as evidence in court to demonstrate guilt. Genovevo Salinas was convicted of a 1992 murder. Salinas cooperated with detectives in answering some questions, but refrained from answering others. He remained silent when questioned about the murder weapon. Prosecutors used his silence as evidence of guilt during trial, which has now been upheld by both Texas courts and the U.S. Supreme Court. Critics say that this decision has compromised a person’s right to remain silent.

The second case being called to attention is Bowman v. Monsanto. An Indiana farmer named Vernon Bowman was sued by agri-giant and seed-modifier Monsanto for purchasing seeds from a grain elevator and planting them in his fields. Monsanto claimed that planting those seeds violated the corporation’s patent rights over them, since they were genetically-modified and considered Monsanto’s intellectual property. Since Bowman “replicated” the company’s intellectual property, he was sued for nearly $85,000.00 in damages. Bowman contended that existing patent law did not cover life forms, and that he had broken no laws. “If they don’t want me to go to the elevator and buy that grain, then Congress should pass a law saying you can’t do it,” said Bowman.

The Supreme Court took up the Bowman case, and disappointingly sided 9-0 with Monsanto. Rather than accurately declaring that the 120-year-old patent law did not offer any legal coverage of self-replicating seeds as they reproduce in perpetuity, the court made a landmark decision and changed the mechanics of patent law forever without an act of Congress. This was the very definition of legislating from the bench, and corporations the leverage they need to punish consumers for “breaking” laws that don’t really accurately cover modern technologies like genetically-modified lifeforms and computer software.

Lastly was the Maryland v. King case, in which the Supreme Court affirmed that a police department may seize DNA as a part of a standard booking procedure — like fingerprinting — for people arrested and accused of a crime. The DNA may then be put into a database, stored indefinitely, and compared to existing cases, despite the fact that the accused person had not yet been convicted of any crimes.

HEALTH CARE LAW THREATENS INDIVIDUAL SOVEREIGNTY & PRIVACY

The Obamacare logo

There are a lot of reasons to object to the mandatory imposition of purchasing corporate services — also known as the “Affordable Care Act.” For brevity and relevance, we will focus here on the aspects that increase the power of the police state.

2013 was the last year that Americans could live and breathe in the United States legally without being compelled to insurance packages from private corporations. Should a person fail or refuse to purchase insurance, he will be subjected to some hefty fines from the federal government, enforced by the IRS.

The fines have been subject to quite a bit of disinformation, and are more significant than most people realize. A common talking point is that the fines are “only” $95, being spread by disinfo agents on the internet and even official radio ads released by the government. The part that is being omitted by these people is that the $95 fine is only valid for a small group of low-income taxpayers, for the first year (2014) only. The fines increase dramatically if the person has an average income or has a family, as well as increasing in stages in 2015 and 2016.

Police State USA discussed the details of the fines in a previous article. We consider the mandates to be a very serious breach of liberty that come with widespread implications.

We also learned this year that the upcoming health care law will include a considerable amount of privacy concerns. With the creation of the “Federal Data Services Hub,” a trove of personal information will be collected on all customers and shared among several agencies. The information “includes, but may not be limited to”: Social Security numbers, income, family size, citizenship and immigration status, gender, ethnicity, email addresses, incarceration records, enrollment status in other health plans, tax information, employment information, patient medical records, pregnancy status, list of disabilities, welfare information, and demographic data (e.g. address, birthdate, physical description…).

All this personal information will be accessible by bureaucrats ranging from the Social Security Administration, the IRS, the Department of Homeland Security, the Veterans Administration, Office of Personnel Management, the Department of Defense and the Peace Corps. And that is in addition to the Medicaid databases linked to the Hub. To be forced into a system such as this by is indeed a great detriment to personal freedom.

THE DORNER MANHUNT

A SWAT team searches a vehicle for Chris Dorner at a roadblock along Highway 38. (Source: Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

One of the most significant stories of 2013 in was the 9-day manhunt for an ex-LAPD officer, Christopher Dorner. After 2 people related to a Los Angeles Police Department captain were shot to death, a manifesto was published online — purportedly by Chris Dorner — claiming responsibility for the acts and threatening more violence against the department. In a city that experiences hundreds of murders per year, this incident would be treated much differently because the targets were police officers. What followed was a horrifying and shameful display of violence and disregard for civil liberties.

A SWAT team searches a home for Chris Dorner in Big Bear Lake. (Source: Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

The manhunt that ensued spanned from oceans to mountains, involving participation from local, state, and federal agents. Roadblocks were set up and vehicles were searched without probable cause; some at gunpoint. When police narrowed their search to the mountain community of Big Bear Lake, California, they began performing house-to-house searches. Some 400-600 homes were searched, as reported by CNN and the Los Angeles Times. The town was blocked off and all vehicles entering and leaving were searched.

The vehicle that contained 2 innocent Latino women delivering newspapers in Torrance, CA. (Source: LA Times)

Four days into the manhunt, with tensions high and paranoia abound, police opened fire on innocent people in two separate incidents; both in the LA suburb of Torrance. The shootings took place minutes apart at separate locations, involving different sets of officers.

The first incident occurred when two newspaper couriers performed their regular delivery route during the early morning hours of February 7th. Unbeknownst to the two delivery women, their route took them directly past the home of one of the VIPs of the Los Angeles Police Department, which was surrounded by police officers as a preemptive security measure. Police watched as the truck made drops along the street. As it drove away from the VIP’s home — making no threat to anyone — eight police officers opened fire at the rear of the truck. The two terrified women huddled up as over 100 rounds riddled their vehicle; popping the tires, shattering the windows, mangling the steel, and hitting both of their bodies. Miraculously, both women survived their wounds.

The incident was a breathtaking display of incompetence and unprovoked aggression. Police had absolutely no idea who they were shooting at. They were seeking a suspect driving a black Nissan Titan. The victims were in a blue Toyota Tacoma. The fugitive was a large, muscular black man with a shaved head. The victims were two Hispanic women; one of them 71-years-old. A total of 102 rounds struck the truck, not counting the other stray shots that whizzed through the residential neighborhood.

(Source: Brad Graverson)

The second incident of unprovoked violence occurred 25 minutes later the same morning. Around 5:45 a.m., a man driving a black truck was on his way to do some early morning surfing before work. He was flagged down by two police officers staking out the neighborhood for Dorner. The officers questioned him, searched his truck, and told him to turn around and head the other direction. He complied.

Moments later, as he traveled the opposite direction on the same road, another police car approached him from ahead. He slowed his truck to the side of the road and expected them to pass. Instead, the police car went into rapid acceleration directly toward him, striking his truck so violently that it knocked one of his wheels off. Police officers then leapt from their car and opened fire on the truck, riddling the windshield with bullets. Miraculously, the man survived.

Again, police had no idea who they were attacking. The victim in this case was a Caucasian man with a small build, and drove a Honda Ridgeline. None of this matched the description of the suspect, and even if it did match, it would not be justifiable cause to immediately attack.

In both cases, the department defended the actions of the officers, kept them on duty, and concealed their identities from the public. At least nine officers were involved in the two incidents of unprovoked aggression, and none of them have been held to any semblance of accountability to the public.

The manhunt concluded with Dorner being surrounded in a cabin in Big Bear, California. Negotiations failed, and gunfire was exchanged. Police quickly resorted to deliberately burning down the cabin in a Waco-style burn out. Pyrotechnic teargas was deployed into the structure and set ablaze with the purpose of burning the suspect alive. Although the sheriff would go on to deny the fire was set intentionally, audio from the incident clearly shows the fire was premeditated and the police had no interest in taking the suspect alive.

THE BOSTON / WATERTOWN LOCKDOWN

Police and National Guard helped to lock down Watertown. (Source: EPA / CJ Gunther)

The incidents that transpired after the attack at the Boston Marathon were nothing short of egregious with respect to civil liberties. On April 15th, two small devices made from pressure cookers exploded at the race, killing 3 and wounding hundreds. An incredible show of force followed, with a deployment of National Guard soldiers all over Boston and rifle-toting police officers standing guard on city streets. Governor Deval Patrick said that Bostonians should expect random checks of their bags and backpacks while in public. The governor said that the “enhanced” police presence and warrantless searches would be an “inconvenience” to residents. Pedestrians were forced to show their identifications to soldiers, bags were searched, and civil rights were generally discarded for the days that followed.

“They can give me a cavity search right now and I’d be perfectly happy,” said one man as he waited for a train.

Police suspected two Chechen brothers as being responsible. On Friday, April 19th, police encountered one of the suspects and engaged him in a firefight. The suspect was killed, but his brother remained at large in the Boston suburb of Watertown, Massachusetts. With this information, over 9,000 police, federal agents, and military personnel from around the country descended upon the the town and put it into complete lock down. Public transportation was suspended. Residents were ordered to stay home and “shelter in place.” Businesses were ordered to remain closed. Roads were barricaded and no one was allowed to leave the town.

A Watertown family is ordered out of their home for a warrantless search. (Source: AP / Reuters

Dramatic photographs began to hit the internet as people remained trapped inside their homes with mobs of police and military filling the streets. Armored vehicles and military Humvees patrolled the town and enforced the lockdown. Agents began performing warrantless house-to-house searches. Police were filmed ripping people from their homes at gunpoint, marching the residents out with their hands raised in submission, and then storming the homes to perform full home searches. While it was unclear initially if the searches were voluntary, videos of the searches and interviews with the residents make it absolutely clear that some of the searches were absolutely NOT voluntary.

THE POLICE STATE IN REVIEW, 2013

While some would have you believe the biggest stories of 2013 were about twerking celebrities and over-hyped real-life courtroom sagas, much bigger events were happening with far more lasting national significance. The foundation of an American police state is already laid and coming into full bloom, while most of the country remains blissfully focused on sports, reality shows, establishment pseudo-news, and other distractions.

While all of the injustices that took place in 2013 would require an encyclopedia to cover adequately, this list is designed to illustrate certain trends and significant stories from the past year. If Americans don’t fix their apathy and disengagement toward causes that matter, we can expect these trends to continue toward their logical conclusions: an increasingly repressive police state dominating the lives people inside these borders and beyond.

CHECKPOINTS, WARRANTLESS SEARCHES BECOME A WAY OF LIFE

(Source: AP/The Sacramento Bee, Randall Benton)

The state of the 4th amendment is in truly bad shape, given the prevalence of warrantless checkpoints and warrantless bag searches being used all around the country for various reasons. No longer restricted to airport terminals, the unconstitutional tactics are now being used in subways, bus stations, on bridges, at parades, and anywhere else the government can get away with them. This is facilitated by the palpable fear of terrorism and with financial incentives from the federal government.

In what was dubbed “Operation Independence,” the federal government along with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department staged a high-visibility terror drill in the LA subway this July. Deputies dressed in paramilitary garbteamed up with agents from the TSA and DHS to require travelers to open up their bags and prove their innocence before being allowed to commute. These tactics have sadly become commonplace in many major cities.

Security measures at major events have gotten increasingly invasive. At the annual ‘Mackinac Bridge Walk’ in St. Ignace, Michigan, up to 40,000 walkers were subjected to warrantless bag searches in the interest of event security. In Chicago, warrantless bag searches were performed on public sidewalks during a celebratory parade for the Blackhawks’ hockey championship, and were again performed along the 26-mile track of the Chicago Marathon. A famous parade in Pasadena, California, is used as an excuse to search the interiors of hundreds of vehicles who wish to park on public streets.

The “stop and frisk” phenomenon was alive and well in 2013. The appalling practice involves police stopping pedestrians, usually pushing them up against a wall and then patting them down, searching their pockets, and opening up their purses and bags. The practice has been notorious in New York City, which not only has aggressive enforcement on the streets but also allows cops to roam around inside private apartment buildings and search tenants. Stop and frisk is also work in Philadelphia, Detroit, northwest Indiana, and other areas.

Sobriety checkpoints have been around a long time, but are increasing in offensiveness. Checks for sobriety have turned into opportunities to search people’s vehicles. People are sometimes being forced off the roads into parking lots and sniffed with dogs in order to be permitted to continue driving down public streets. Some sobriety checkpoints are being dubbed “no refusal” because anyone who refuses to prove their innocence through a breath test will be strapped down to a table and have their blood forcibly taken from them. New saliva swab analyzers now allows police to detect and arrest people based on on them having things like marijuana and prescription drugs in their systems while driving.

Not to be outdone by local cops, the federal government is setting up checkpoints in reportedly 60 communities to take blood and saliva samples from drivers in a multi-million dollar “survey.”

The reasons for warrantless searches is only limited by the imaginations of the police. There are now regular license and vehicle inspection checkpoints, fruit possession checkpoints, firework possession checkpoints, tampon possession searches, searches for canned beverages, roadside smog checkpoints, and more.

DOD PROGRAM 1033 MILITARIZING LOCAL POLICE DEPARTMENTS

MRAP vehicles

Those who are paying attention are seeing the constant notices of military equipment from overseas war-zones being dispersed to domestic police departments. These giveaways are usually in the form of armored vehicles (as far as the public knows). This is all made possible by the Defense Department’s Program 1033. In place since 1997, the program allows the DOD to give away the equipment — often free of charge — to local police departments who apply for the equipment grants.

This year has been the year of the MRAP, or Mine Resistant Armor Protected vehicle. For the first time these fighting vehicles, costing an upwards of $600,000 each, are being sent out to American cops, and in rapid fashion. The hulking trucks, which come with armor plating, gun ports, bullet-proof glass, and a gun turret on top, end up being used on SWAT raids in residential America.

The program dispersed more than half a billion dollars worth of equipment in 2012, and 2013 is expected to keep that pace, if not exceed it. There is no oversight over Program 1033 and the Department of Defense has never been audited, meaning there is overwhelming room for fraud and abuse. The U.S. taxpayers have been burdened with purchasing this equipment and now it is being given away without compensation; without auction. And no one really knows the full scope of the project.

One does not have to look far for examples of local departments becoming militarized. MRAP acquisitions have taken place in every state, the latest including Alabama, Indiana, Texas, Idaho, California, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois, and Nevada.

To understand the implications of what a militarized police force is capable of, consider the extravagant anti-terror drill performed by LAPD this year at the National Homeland Security Association’s conference in June. Gunfire echoed through downtown Los Angeles, bombs exploded, and helicopters swooped low among tall office buildings in a demonstrated response to two terrorists in a pickup truck. Paramilitary police pulled up in a bomb-dropping armored vehicle, and engaged in a mock firefight. Guests from around the nation and world attended the conference to marvel at militarized law enforcement in action. The performance was funded by the federal government and was designed to inspire more departments to become militarized.

THE TSA CONTINUES TO EXPAND ITS REACH

The Transportation Security Administration had another year characterized by abuse, theft, and violations of civil rights. There was a steady stream of children being tormented, property being stolen, and genitals being grabbedthis year, as usual. Americans are being searched without probable cause or warrants while being threatened with arrest over loudspeakers if they talk back to the checkpoint agents. There are too many of these stories to count and this behavior has been standard operating procedure since the TSA was created. Some of the agency’s recent advancements deserve to be mentioned, however.

Checkpoints are now involving a much deeper look into traveler’s private personal information. Nothing short of a criminal background check will allow a person to fly in America anymore. The new security program involves gaining access to travelers’ private employment information, vehicle registrations, travel history, property ownership records, physical characteristics, tax identification numbers, past travel itineraries, law enforcement information, “intelligence” information, passport numbers, frequent flier information, and other “identifiers” linked to DHS databases. The TSA is allowing people to purchase the title of “trusted traveler” if they willingly submit their biometric fingerprint scans into a FBI database, submit to a criminal background check, and pay the TSA a fee of $85.00 for a five-year PreCheck membership.

The TSA has evidently expanded its reach to parking lots this year, after encouraging and overseeing airport security plans that involve opening up parked cars and performing warrantless searches on their interiors. Although the TSA may not be directly involved with performing these searches, they are approved by the TSA and some airports claim they are mandated by the TSA.

The response of may Americans is to avoid the TSA by ceasing air travel. This is a shortsighted solution, as the TSA has never been bound to airports. As one TSA official pointed out, “We are not the Airport Security Administration.” Indeed, avoiding the TSA became more challenging in 2013, and is bound to become more difficult in the future.

TSA agents are not making regular appearances on other modes of transportation. Special armed TSA units — known as VIPR teams — are showing up at public venues, sporting events, train terminals, music festivals, rodeos, highway weigh stations in order to “surprise” the terrorists with “suspicionless” searches. “The security at airports has increased so the bad guys are now traveling on the trains and buses,” said TSA agent George Robinson at a surprise TSA “Spot Checks” at an Austin railway. The TSA was active in and around the Superbowl this year, one of many places many never expected to see the TSA operating.

To soften their villainous image, the TSA has been spending taxpayer money to produce cartoons designed to propagandize children into accepting warrantless checkpoints. Getting searched by strangers in uniformed is presented as fun and exciting — and vital to safety.

THE SURVEILLANCE STATE, REVEALED

(Warner Brothers)

This year we experienced a lot of mainstream discussion about the breadth of the Federal Government’s domestic surveillance grid, in large part due to the revelations from NSA contractor-gone-rogue, Edward Snowden. Snowden discovered over the course of his employment with the NSA that the American public was completely unaware of the extent of spying being performed by the government on its own people, and felt compelled to go public. In June, Snowden went to journalist Glenn Greenwald with up to 200,000 NSA documents to prove what the government was up to. Greenwald has since released a series of damning articles exposing the NSA spy grid, which have received international attention.

Now officially charged by the U.S. government with espionage, Snowden has been in hiding overseas for over 6 months. But his leaks have provided valuable insight into the operation of the government. Its a bit ironic that the man exposing the spy program is labeled the spy, but I digress.

Greenwald’s articles have revealed that the NSA’s modus operandi is to “collect it all,” meaning every collectible form of communication or data. To this end, the NSA has been utilizing what it calls the Prism program, under which the agency has obtained direct access to the systems of Google, Facebook, Apple and other US internet giants. With this access to internet traffic, the NSA uses a program called XKeyscore, which is surveillance tool that collects “nearly everything a user does on the internet.” One presentation of XKeyscore claims the program collects the content of emails, websites visited and searches, as well as their metadata.

“I, sitting at my desk,” Snowden said, could “wiretap anyone, from you or your accountant, to a federal judge or even the president, if I had a personal email”.

Another recent leak revealed that the NSA is “getting vast volumes” of records of individual’s physical locations from their cell phones — faster than it can process and store — as the agency surveils the nation’s mobile phone networks. It goes deeper than that though. Greenwald reported that the NSA is collecting information about phone calls from millions of Americans daily. Such information includes the numbers of both parties on the call, their locations, the time, and the duration of all calls made on the network.

BORDER SECURITY AS OPPRESSIVE AS EVER

Vehicles are searched indiscriminately at a border checkpoint. (Source: Eric Gay/AP Photo)

A constant barrage of stories of abuse from U.S. Customs and Border Patrol have arisen in 2013. These did not only occur at the physical borders, but at the numerous domestic checkpoints that appear all over U.S. roadways across the southwest. Up to 100 miles into the country, permanent roadblocks exist where travelers are asked by federal agents to prove their citizenship and often subjected to searches and other harassment.

At one such internal checkpoint in California, a man named Robert Trudell decided he was going to remain silent in his car until the agents let him continue traveling down the roadway. As he calmly sat in his car and photographed the scene, agents bashed in his window with a club and extracted him from his car. Police State USA has viewed numerous other videos of harassment at border patrol checkpoints, and find their prominent existence on U.S. highways to be very disconcerting.

Earlier this year, the official watchdog over civil rights for the Department of Homeland Security gave the green light for “suspicionless” seizure of any electronics they encounter from travelers crossing the border. Thousands of laptops, cell phones, and other personal property has been confiscated by customs agents, forcing the owner to spend lots of time and money to attempt to reclaim the items — not to mention the loss of privacy suffered by the owners.

Border Patrol and DHS has taken an interest in harassing small aircraft pilots as well, as we have seen multiple such stories this year. Reports follow a pattern: CBP agents approach pilots, request aviation paperwork, and conduct an extensive searches of their aircraft, often including removal of all contents. Agents have been tight-lipped about the reason or justification for these warrantless searches. Taking the harassment up a notch, DHS ordered one hobbyist glider pilot named Robin Fleming to the ground for a search. He says he was threatened with being shot down from the sky.

THE DESTRUCTIVE DRUG WAR WAGES ON

DEA agents (Source: Mark Wilson/AP Photo)

The War on Drugs has been the source of incomprehensible levels of injustice, government corruption, brutality, and abuse for decades in the United States. Although year 2013 represents no marked difference from the status quo, these Drug War abuses constitute far too great a threat to go unmentioned in this list.

We saw countless people imprisoned for non-violent, victimless crimes. I say countless because the numbers are truly unknown when considering all of the federal, state, county, and city-level jails housing inmates for drugs. What we do know is that there 1,571,013 prisoners in state and federal prisons in 2012, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Of the federal inmates, around half of the prisoners are being locked up because of the War on Drugs. The number of lives ruined in the name of prohibition cannot possibly be tallied. Many are going to prison for decades — even life imprisonment — without ever having committed a violent offense. One such example was the case of Jerry Duval, a farmer who was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison for growing marijuana for medicinal use in the manner he was licensed to in the state of Michigan.

The Drug War gives the government the perfect vehicle for expanding its ability to legally steal from citizens, and this year has been no exception. Thanks to a legal maneuver known as Civil Asset Forfeiture, government agents can confiscate property and cash from anyone that they merely “suspect” of being involved in the drug trade. Thanks to recent advancements in domestic spying capabilities, the DEA has managed to double its amount of seizures since 2001. The owners of the seized property don’t even have to be charged with a crime, but often have to spend a small fortune in court to prove their innocence and get their possessions back. This practice varies across the country, but the prospect of keeping seized property provides a direct incentive for confiscation in any agency where it is used. For Darren Kent, a disabled widower in New Jersey, Drug War forfeiture could allow police to confiscate his house, his bank account, his 2 vehicles, and other property — all because of illegal plants he allegedly grew in his basement.

The enforcement of these silly drug laws has become increasingly aggressive and brutal. When someone is suspected of committing a non-violent drug offense, there is often a team of masked, paramilitary SWAT agents sent in the middle of the night to break down the doors and windows of their home, hold the occupants at gunpoint, and shoot any family pets that dare to challenge their presence. As one could imagine, this insane policy of “no-knock raids” over drugs leads to an unending torrent of violence and bloodshed inside people’s homes. In 2013, Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputies gunned down 80-year-old Eugene Mallory in his bed during a legal home-invasion to investigate if he was making meth. Earlier this month, police negligently shot Krystal Barrows, mother of three, in the head during a drug raid in Chillicothe, Ohio.

In case its not obvious, prohibition laws leave open the legal doorways for many innocent people to feel the brunt of the police state. In 2013, a family of maple syrup farmers in Illinois was raided on suspicion of making meth. TheHarte family of Kansas says that after buying hydroponics equipment for their indoor garden, police stormed their house in a manner that reminded them of Navy SEALs storming the bin Laden residence. Urban garden advocate John Kohler, of GrowingYourGreens.com, had his home searched because police thought he might be growing illegal plants in his house. One does not have to look far for more examples of drug raids gone bad.

Not even the elderly can escape from the harassment of strident drug enforcers have. Tennessee police pulled over and harassed an elderly couple because their car had a Ohio State University bumper sticker that the police officer thought might represent a marijuana leaf. A Utah man’s final moments with his recently-deceased wife were rudely interrupted when police barged into his home to confiscate her prescription painkillers.

It should be obvious that drug prohibition gives perverts and sexual predators a convenient place to legally abuse citizens while getting paid to do so. In June, a story broke about a female driver being asked to lift her shirt and shake her bra multiple times for a police officer who wanted her to prove she didn’t have drugs packed in it. In Texas, two bikini-clad women were given cavity searches on the side of the highway. “You’re going to go up my private parts?” Brandy Hamilton asked the officer. “Yes, ma’am,” the officer responded, before jamming a finger into each of their crotches with the same glove.

These forced cavity searches were a regular occurrence in 2013, in what can only be described as cases of legal rape. After rolling a stop sign, David Eckert of Deming, Utah, was detained and taken to a hospital, and for hours he was subjected to manual finger probes of his anus, forced to take an enema and defecate in front of police officers, forcibly X-rayed, and ultimately given a full-blown colonoscopy to attempt to find drugs in his colon. And this case is not unique. An American woman returning to the United States from Mexico was detained at the border near El Paso, chained to a hospital bed and given a forcible gynecological exam, involving finger penetration, forced defecation, and X-rays and a CT-scan. A 26-year-old Oregon man named Jason Barnes was forcibly catheterized by police after he was stopped by police for riding a bicycle without lights.

Stories from 2013 also should have made it glaringly obvious how easy it is to wrongly convict people and ruin innocent lives. In February, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that “a court can presume” an alert by a drug-sniffing dog provides probable cause for a search, even if the dot is not fully trained and lacks any documentation of its accuracy record. If animals deciding your fate is not disconcerting enough, consider what happens when the government agents decide to say you possessed contraband when you actually didn’t. Tens of thousands of drug cases may have been corrupted by a Massachusetts crime-lab chemist named Annie Dookhanwho collaborated with prosecutors to achieve more convictions. A Georgia judge ordered police officers to frame a woman with drugs after she refused to have sex with him. The potential for abusing “possession” laws are endless.

SCHOOLS GROOM CHILDREN FOR LIFE IN POLICE STATE USA

(Source: Yuma Sun / AP)

Government schools have always been the source of indoctrination and inadequate education, but the rise of security hysteria and zero-tolerance policies has made them into veritable conditioning centers for life in the American police state.

As a matter of policy in most compulsory government schools, students are subjected to warrantless searches of their bags and lockers, dog sniffs, and are even being forced to give urine samples without probable cause. Drug enforcement and education takes on a variety of different forms. In Indiana, police officers subjected a class of 5th graders to a “simulated drug raid” in a “drug awareness” event that resulted in one student getting attacked by the police dog that was demonstrating how it might children for drugs if the police were crashing a party at someone’s home.

With modern technology, they are being watched and listened under sophisticated surveillance systems, sometimes which are fed directly to police departments. Some schools are making students are having to carry RFID badges or use biometric scanners to track attendance and movement. Their bodies are forced to endure mass-medication at earlier and earlier ages.

Many schools use what have been known as “isolation booths” for children who misbehave, which in practice are tantamount to solitary confinement in a dark closet.

Parking lots are subject to warrantless searches; some so draconian that high school students are getting felonies for leaving pocket knives locked in their cars. In fact, it is common to have police officers regularly in school so administrators can outsource discipline to courts and jails. An undercover cop disguised as a high-schooler in Temecula, California, befriended an autistic boy and convinced him to purchase marijuana in order to arrest him.

The curriculum is unsurprisingly pro-statism, with recent (and glaring) examples involving students being asked to justify repealing amendments out of the Bill of Rights and being taught that government is like “family” and should be obeyed.

In addition, schools are being locked down at every possible opportunity. A school in Idaho went into “full prison mode” when a student brought a folding shovel. A Long Island school went into lockdown when a child had a lime green Nerf toy.

The lockdowns are becoming so routine that police departments and schools are running terror drills to make sure they run smoothly. The El Paso SWAT team staged a “surprise” terror drill in a school in which police charged into the school, used simulated gunfire, and detonated concussion grenades while they took over the school — to the surprise of everyone except for the principal. A similar terror drill was conducted in a Chicago school “in an effort to provide our teachers and students some familiarity with the sound of gunfire.” An Oregon school hired a man to wear a mask and carry a realistic gun into a faculty meeting and surprise teachers with realistic sounding gunfire in order to test their “readiness.” In Ohio, a mock hijacking was staged on a school bus containing children so that the SWAT team could practice its explosive rescue techniques.

MORE DANGEROUS DECISIONS FROM THE SUPREME COURT

The Supreme Court

SCOTUS made a few rulings in 2013 regarding the police state. While certainly not the worst court decisions we’ve endured, they can be added to a long list of bad ones.

In Salinas v. Texas, the court ruled 5-4 that when a suspect doesn’t answer a question during an interrogation, his silence can be used as evidence in court to demonstrate guilt. Genovevo Salinas was convicted of a 1992 murder. Salinas cooperated with detectives in answering some questions, but refrained from answering others. He remained silent when questioned about the murder weapon. Prosecutors used his silence as evidence of guilt during trial, which has now been upheld by both Texas courts and the U.S. Supreme Court. Critics say that this decision has compromised a person’s right to remain silent.

The second case being called to attention is Bowman v. Monsanto. An Indiana farmer named Vernon Bowman was sued by agri-giant and seed-modifier Monsanto for purchasing seeds from a grain elevator and planting them in his fields. Monsanto claimed that planting those seeds violated the corporation’s patent rights over them, since they were genetically-modified and considered Monsanto’s intellectual property. Since Bowman “replicated” the company’s intellectual property, he was sued for nearly $85,000.00 in damages. Bowman contended that existing patent law did not cover life forms, and that he had broken no laws. “If they don’t want me to go to the elevator and buy that grain, then Congress should pass a law saying you can’t do it,” said Bowman.

The Supreme Court took up the Bowman case, and disappointingly sided 9-0 with Monsanto. Rather than accurately declaring that the 120-year-old patent law did not offer any legal coverage of self-replicating seeds as they reproduce in perpetuity, the court made a landmark decision and changed the mechanics of patent law forever without an act of Congress. This was the very definition of legislating from the bench, and corporations the leverage they need to punish consumers for “breaking” laws that don’t really accurately cover modern technologies like genetically-modified lifeforms and computer software.

Lastly was the Maryland v. King case, in which the Supreme Court affirmed that a police department may seize DNA as a part of a standard booking procedure — like fingerprinting — for people arrested and accused of a crime. The DNA may then be put into a database, stored indefinitely, and compared to existing cases, despite the fact that the accused person had not yet been convicted of any crimes.

HEALTH CARE LAW THREATENS INDIVIDUAL SOVEREIGNTY & PRIVACY

The Obamacare logo

There are a lot of reasons to object to the mandatory imposition of purchasing corporate services — also known as the “Affordable Care Act.” For brevity and relevance, we will focus here on the aspects that increase the power of the police state.

2013 was the last year that Americans could live and breathe in the United States legally without being compelled to insurance packages from private corporations. Should a person fail or refuse to purchase insurance, he will be subjected to some hefty fines from the federal government, enforced by the IRS.

The fines have been subject to quite a bit of disinformation, and are more significant than most people realize. A common talking point is that the fines are “only” $95, being spread by disinfo agents on the internet and even official radio ads released by the government. The part that is being omitted by these people is that the $95 fine is only valid for a small group of low-income taxpayers, for the first year (2014) only. The fines increase dramatically if the person has an average income or has a family, as well as increasing in stages in 2015 and 2016.

Police State USA discussed the details of the fines in a previous article. We consider the mandates to be a very serious breach of liberty that come with widespread implications.

We also learned this year that the upcoming health care law will include a considerable amount of privacy concerns. With the creation of the “Federal Data Services Hub,” a trove of personal information will be collected on all customers and shared among several agencies. The information “includes, but may not be limited to”: Social Security numbers, income, family size, citizenship and immigration status, gender, ethnicity, email addresses, incarceration records, enrollment status in other health plans, tax information, employment information, patient medical records, pregnancy status, list of disabilities, welfare information, and demographic data (e.g. address, birthdate, physical description…).

All this personal information will be accessible by bureaucrats ranging from the Social Security Administration, the IRS, the Department of Homeland Security, the Veterans Administration, Office of Personnel Management, the Department of Defense and the Peace Corps. And that is in addition to the Medicaid databases linked to the Hub. To be forced into a system such as this by is indeed a great detriment to personal freedom.

THE DORNER MANHUNT

A SWAT team searches a vehicle for Chris Dorner at a roadblock along Highway 38. (Source: Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

One of the most significant stories of 2013 in was the 9-day manhunt for an ex-LAPD officer, Christopher Dorner. After 2 people related to a Los Angeles Police Department captain were shot to death, a manifesto was published online — purportedly by Chris Dorner — claiming responsibility for the acts and threatening more violence against the department. In a city that experiences hundreds of murders per year, this incident would be treated much differently because the targets were police officers. What followed was a horrifying and shameful display of violence and disregard for civil liberties.

A SWAT team searches a home for Chris Dorner in Big Bear Lake. (Source: Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

The manhunt that ensued spanned from oceans to mountains, involving participation from local, state, and federal agents. Roadblocks were set up and vehicles were searched without probable cause; some at gunpoint. When police narrowed their search to the mountain community of Big Bear Lake, California, they began performing house-to-house searches. Some 400-600 homes were searched, as reported by CNN and the Los Angeles Times. The town was blocked off and all vehicles entering and leaving were searched.

The vehicle that contained 2 innocent Latino women delivering newspapers in Torrance, CA. (Source: LA Times)

Four days into the manhunt, with tensions high and paranoia abound, police opened fire on innocent people in two separate incidents; both in the LA suburb of Torrance. The shootings took place minutes apart at separate locations, involving different sets of officers.

The first incident occurred when two newspaper couriers performed their regular delivery route during the early morning hours of February 7th. Unbeknownst to the two delivery women, their route took them directly past the home of one of the VIPs of the Los Angeles Police Department, which was surrounded by police officers as a preemptive security measure. Police watched as the truck made drops along the street. As it drove away from the VIP’s home — making no threat to anyone — eight police officers opened fire at the rear of the truck. The two terrified women huddled up as over 100 rounds riddled their vehicle; popping the tires, shattering the windows, mangling the steel, and hitting both of their bodies. Miraculously, both women survived their wounds.

The incident was a breathtaking display of incompetence and unprovoked aggression. Police had absolutely no idea who they were shooting at. They were seeking a suspect driving a black Nissan Titan. The victims were in a blue Toyota Tacoma. The fugitive was a large, muscular black man with a shaved head. The victims were two Hispanic women; one of them 71-years-old. A total of 102 rounds struck the truck, not counting the other stray shots that whizzed through the residential neighborhood.

(Source: Brad Graverson)

The second incident of unprovoked violence occurred 25 minutes later the same morning. Around 5:45 a.m., a man driving a black truck was on his way to do some early morning surfing before work. He was flagged down by two police officers staking out the neighborhood for Dorner. The officers questioned him, searched his truck, and told him to turn around and head the other direction. He complied.

Moments later, as he traveled the opposite direction on the same road, another police car approached him from ahead. He slowed his truck to the side of the road and expected them to pass. Instead, the police car went into rapid acceleration directly toward him, striking his truck so violently that it knocked one of his wheels off. Police officers then leapt from their car and opened fire on the truck, riddling the windshield with bullets. Miraculously, the man survived.

Again, police had no idea who they were attacking. The victim in this case was a Caucasian man with a small build, and drove a Honda Ridgeline. None of this matched the description of the suspect, and even if it did match, it would not be justifiable cause to immediately attack.

In both cases, the department defended the actions of the officers, kept them on duty, and concealed their identities from the public. At least nine officers were involved in the two incidents of unprovoked aggression, and none of them have been held to any semblance of accountability to the public.

The manhunt concluded with Dorner being surrounded in a cabin in Big Bear, California. Negotiations failed, and gunfire was exchanged. Police quickly resorted to deliberately burning down the cabin in a Waco-style burn out. Pyrotechnic teargas was deployed into the structure and set ablaze with the purpose of burning the suspect alive. Although the sheriff would go on to deny the fire was set intentionally, audio from the incident clearly shows the fire was premeditated and the police had no interest in taking the suspect alive.

THE BOSTON / WATERTOWN LOCKDOWN

Police and National Guard helped to lock down Watertown. (Source: EPA / CJ Gunther)

The incidents that transpired after the attack at the Boston Marathon were nothing short of egregious with respect to civil liberties. On April 15th, two small devices made from pressure cookers exploded at the race, killing 3 and wounding hundreds. An incredible show of force followed, with a deployment of National Guard soldiers all over Boston and rifle-toting police officers standing guard on city streets. Governor Deval Patrick said that Bostonians should expect random checks of their bags and backpacks while in public. The governor said that the “enhanced” police presence and warrantless searches would be an “inconvenience” to residents. Pedestrians were forced to show their identifications to soldiers, bags were searched, and civil rights were generally discarded for the days that followed.

“They can give me a cavity search right now and I’d be perfectly happy,” said one man as he waited for a train.

Police suspected two Chechen brothers as being responsible. On Friday, April 19th, police encountered one of the suspects and engaged him in a firefight. The suspect was killed, but his brother remained at large in the Boston suburb of Watertown, Massachusetts. With this information, over 9,000 police, federal agents, and military personnel from around the country descended upon the the town and put it into complete lock down. Public transportation was suspended. Residents were ordered to stay home and “shelter in place.” Businesses were ordered to remain closed. Roads were barricaded and no one was allowed to leave the town.

A Watertown family is ordered out of their home for a warrantless search. (Source: AP / Reuters

Dramatic photographs began to hit the internet as people remained trapped inside their homes with mobs of police and military filling the streets. Armored vehicles and military Humvees patrolled the town and enforced the lockdown. Agents began performing warrantless house-to-house searches. Police were filmed ripping people from their homes at gunpoint, marching the residents out with their hands raised in submission, and then storming the homes to perform full home searches. While it was unclear initially if the searches were voluntary, videos of the searches and interviews with the residents make it absolutely clear that some of the searches were absolutely NOT voluntary.