- Forums

- BGOL Primary Forums

- Blackgirl Online

- Gone But Not Forgotten - R.I.P. Forum

- Celebrity R.I.P. Threads

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

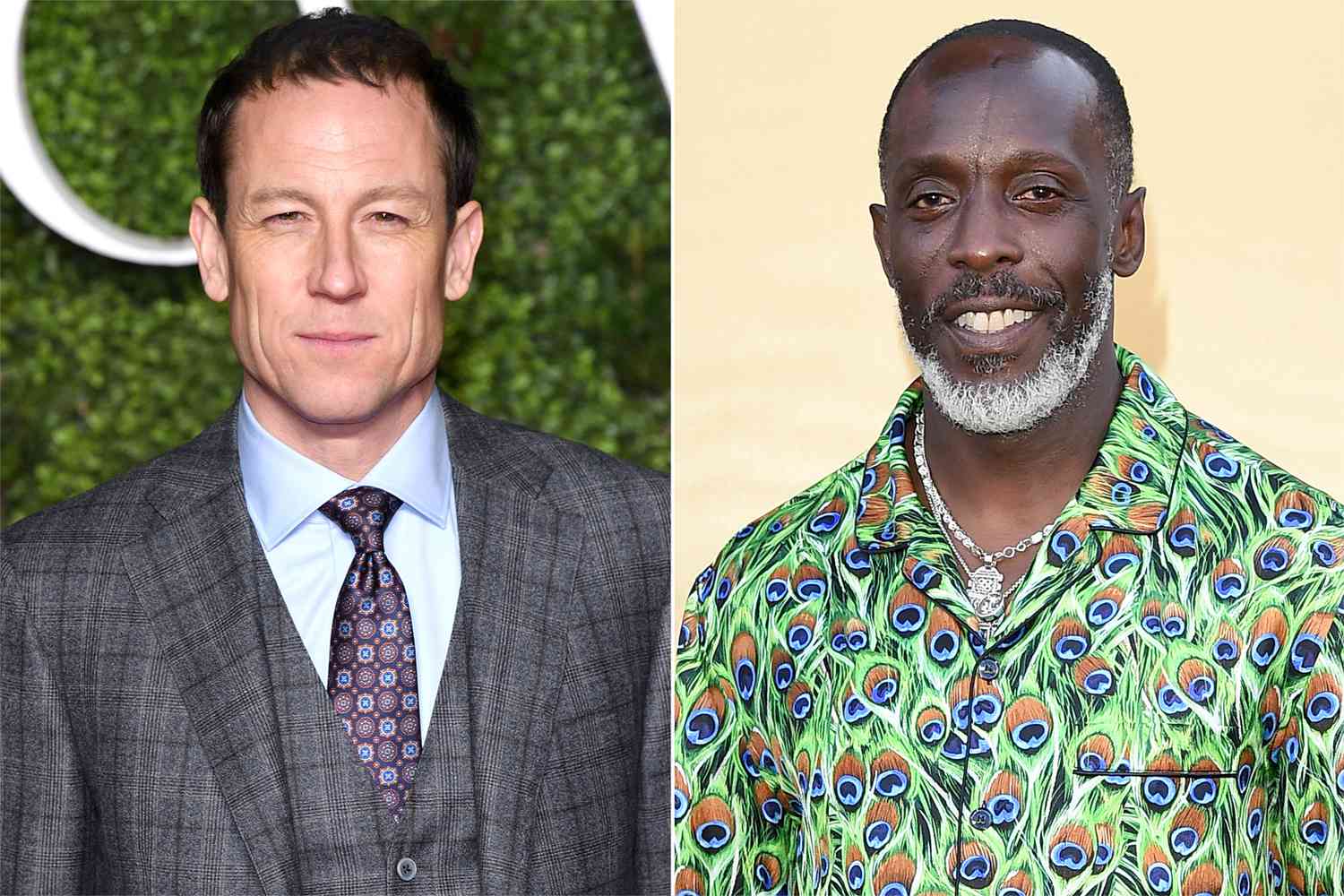

The Wire’ actor Michael K. Williams found dead in NYC apartment

- Thread starter Supersav

- Start date

I didn't watch the Wire until this past Christmas so my introduction to the brother's acting was from other roles. Everything I've seen him in was must see TV. Brother commanded the screen like very few people and I was looking forward to future performances from him R.I.P Michael K. Williams you will be missed.

In the Vanderveer Projects, Michael K. Williams Was Another Kind of Star

By Saki Knafo

Williams at the Vanderveer Estates, where he grew up. Photo: Demetrius Freeman/The New York Times/Redux

The housing project known as Vanderveer Estates consists of 59 red-brick buildings bound by Nostrand and Foster Avenues in East Flatbush, Brooklyn. One night a few months ago, the actor Michael K. Williams stood in front of one of those buildings and gave a speech. “I love my hood,” he said, hoarse with emotion. “I’m born and raised on these streets.” He was wearing a white hooded sweatshirt and white sweatpants, with a white face mask pulled down under his chin, and in the bright lights of the courtyard, he seemed to glow. Scanning the faces in the crowd, he said he had come back home to Vanderveer (or Flatbush Gardens, as it is now officially called) to deliver a message to the neighborhood’s youth. “We can be together,” he insisted. “We can love on each other. It’s possible.”

Williams gave many speeches in recent years, often on the streets of Brooklyn’s Black neighborhoods. As one of the founders of a nonprofit organization called We Build the Block, he presided over a series of unconventional gatherings throughout the borough — block parties where teenage organizers registered their neighbors to vote. He also backed a candidate for City Council, spent hours engaging groups of young people in private conversations, and traveled around the country showing a film he’d made about the incarceration of teenagers to anyone willing to see it — judges, cops, incarcerated teens themselves. When he spoke, he assumed a sort of fighting stance, his shoulders squared and nostrils flared, conveying the same combination of ferocity and tenderness that had defined his portrayal of Omar Little, one of television’s most indelible roles. Back in Vanderveer, some of his old friends called him “the prophet of the projects,” and it wasn’t hard to see why. With the white beard he sometimes wore, his intense gaze, and his fierce appeals for justice and love, he could put you in mind of the holy men of the Bible.

On Monday, Williams was found dead of a suspected overdose in his Williamsburg apartment. He was 54. This week, as the world mourned the loss of a great actor, people in Flatbush grappled with the loss of something greater. His friends and family remembered him as a rare kind of person, someone from a very hard place with a very soft heart. “Mike believed that it was important to be loved and to feel love,” his nephew Dominic Dupont said. “He showed that through how he treated people.”

Williams lived in Vanderveer until he filmed the second season of The Wire. His building overlooked a courtyard known as the Terrace. “We called ourselves Terrace Massive,” Alvin Washington, a childhood friend, recalled. “It was about 15 of us. A little crew.” Of those 15 or so friends, nearly half have died. According to Washington, only Williams and maybe one other boy avoided doing time. “Mike will tell you in three seconds, he’s not a gangster,” he said, laughing. “He was a free soul. If he felt like dancing, he danced. If he felt like crying, he cried.”

Washington was serving an eight-year sentence for robbery when The Wire came out. He and the other men in his cellblock would crowd into the day room to watch it. “Ain’t no talking when it was on,” he said. When he got out of jail, Williams gave him a box set of the series and a collection of designer clothes that people had sent him. He took him to parties and introduced him to celebrities. “I know mad people who come from where he came from and don’t pick nobody up,” Washington said. “They just brush you off, because you might still be a criminal or something, but Mike looked past that and saw the person.” Recently, Williams started a production company, Freedome, with the goal of producing work by local Black artists. He planned to cast people from the community in minor roles. “Everybody would get to eat off of it,” Washington said, “because that’s how he designed it.”

Dupont, Williams’s nephew, said he believed Williams’s vision for the company would still come to fruition. “We will continue to move forward in a direction that’s consistent with Michael’s vision for the world,” he told me. He was speaking on the phone from Williams’s apartment in Williamsburg, where, two days earlier, he had found his uncle’s body. He said the love that Williams had shown him throughout his life had, in a strange way, enabled him to get through that moment. “He helped prepare me to deal with tough situations,” he said.

Those situations included a 25-year prison sentence. When Dupont was 19, he was convicted of murdering a man who had attacked his brother. “My relationship with Mike before prison was close, and those 40-foot walls did not change that,” he said. Some 20 years into his sentence, in 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo granted him clemency, a decision that prison officials attributed to Dupont’s outstanding work as a youth counselor. Dupont, in turn, credited Williams with helping him become a leader. “Mike fostered those things in me,” he said.

Shortly before Dupont got out, he and Williams made Raised in the System, a documentary for VICE on HBO about America’s mass incarceration of teenagers. In interviews, Williams has said this was a transformative experience, the beginning of a quest to understand and address the root causes of the suffering in his community. It was through this work that he got to know Edwin Raymond, a police lieutenant and activist from East Flatbush. In 2015, Raymond and 11 other Black and brown officers had sued the city, alleging that the NYPD had pressured them to engage in discriminatory practices. Last year, Williams brought Raymond to the Academy Awards. On the red carpet, he declined to speak to any reporter who didn’t interview Raymond first. “He was someone who never forgot the hood,” Raymond said. “He used his influence as much as possible to lift up people beyond him.”

One of those people was Alvin Washington’s son, AJ. Over the past year, AJ, who is 15, has recorded dozens of episodes of a video podcast in his family’s Vanderveer apartment. Called Old2New, it features his conversations with older members of the community — “people who’s been through the street life and in jail, stuff like that,” he told me.

In February, Williams appeared on the show. For a half hour, he answered AJ’s questions with remarkable thoughtfulness and vulnerability. At one point, he observed that people deal with pain and anger in different ways. “For me, I turn my pain inward, and I hurt myself,” he said. Others hurt those around them. “So it’s all about, we gotta love each other no matter what,” he said. “We gotta lift each other up.”

“We should help each other instead of fighting each other,” AJ said, agreeing. “You don’t gotta take each other’s life.”

“You said some valuable words right there, man,” Williams replied. He looked into the distance, gathering his thoughts. “As I get older,” he said, “I start to realize that our inability to communicate with each other as Black men and women — that was on purpose. When they brought us here as slaves, they took away our language, our culture, our spirituality, our religion. They stripped all of that away from us.” He added, “I was made to slit your throat so I could eat.”

As the conversation wound down, AJ told Williams that he looked up to him. “I just want to be like you,” he said with a shy smile. Williams raised his eyebrows and wagged a finger. “Oh no, no, no,” he said. “Do me one favor, nephew. Don’t be like me. Be better than me. Stand on these shoulders and take it higher.” He assured AJ that he was already on his way. “Be great,” he said. “Greater than me. Please. You hear me?”

By Saki Knafo

Williams at the Vanderveer Estates, where he grew up. Photo: Demetrius Freeman/The New York Times/Redux

The housing project known as Vanderveer Estates consists of 59 red-brick buildings bound by Nostrand and Foster Avenues in East Flatbush, Brooklyn. One night a few months ago, the actor Michael K. Williams stood in front of one of those buildings and gave a speech. “I love my hood,” he said, hoarse with emotion. “I’m born and raised on these streets.” He was wearing a white hooded sweatshirt and white sweatpants, with a white face mask pulled down under his chin, and in the bright lights of the courtyard, he seemed to glow. Scanning the faces in the crowd, he said he had come back home to Vanderveer (or Flatbush Gardens, as it is now officially called) to deliver a message to the neighborhood’s youth. “We can be together,” he insisted. “We can love on each other. It’s possible.”

Williams gave many speeches in recent years, often on the streets of Brooklyn’s Black neighborhoods. As one of the founders of a nonprofit organization called We Build the Block, he presided over a series of unconventional gatherings throughout the borough — block parties where teenage organizers registered their neighbors to vote. He also backed a candidate for City Council, spent hours engaging groups of young people in private conversations, and traveled around the country showing a film he’d made about the incarceration of teenagers to anyone willing to see it — judges, cops, incarcerated teens themselves. When he spoke, he assumed a sort of fighting stance, his shoulders squared and nostrils flared, conveying the same combination of ferocity and tenderness that had defined his portrayal of Omar Little, one of television’s most indelible roles. Back in Vanderveer, some of his old friends called him “the prophet of the projects,” and it wasn’t hard to see why. With the white beard he sometimes wore, his intense gaze, and his fierce appeals for justice and love, he could put you in mind of the holy men of the Bible.

On Monday, Williams was found dead of a suspected overdose in his Williamsburg apartment. He was 54. This week, as the world mourned the loss of a great actor, people in Flatbush grappled with the loss of something greater. His friends and family remembered him as a rare kind of person, someone from a very hard place with a very soft heart. “Mike believed that it was important to be loved and to feel love,” his nephew Dominic Dupont said. “He showed that through how he treated people.”

Williams lived in Vanderveer until he filmed the second season of The Wire. His building overlooked a courtyard known as the Terrace. “We called ourselves Terrace Massive,” Alvin Washington, a childhood friend, recalled. “It was about 15 of us. A little crew.” Of those 15 or so friends, nearly half have died. According to Washington, only Williams and maybe one other boy avoided doing time. “Mike will tell you in three seconds, he’s not a gangster,” he said, laughing. “He was a free soul. If he felt like dancing, he danced. If he felt like crying, he cried.”

Washington was serving an eight-year sentence for robbery when The Wire came out. He and the other men in his cellblock would crowd into the day room to watch it. “Ain’t no talking when it was on,” he said. When he got out of jail, Williams gave him a box set of the series and a collection of designer clothes that people had sent him. He took him to parties and introduced him to celebrities. “I know mad people who come from where he came from and don’t pick nobody up,” Washington said. “They just brush you off, because you might still be a criminal or something, but Mike looked past that and saw the person.” Recently, Williams started a production company, Freedome, with the goal of producing work by local Black artists. He planned to cast people from the community in minor roles. “Everybody would get to eat off of it,” Washington said, “because that’s how he designed it.”

Dupont, Williams’s nephew, said he believed Williams’s vision for the company would still come to fruition. “We will continue to move forward in a direction that’s consistent with Michael’s vision for the world,” he told me. He was speaking on the phone from Williams’s apartment in Williamsburg, where, two days earlier, he had found his uncle’s body. He said the love that Williams had shown him throughout his life had, in a strange way, enabled him to get through that moment. “He helped prepare me to deal with tough situations,” he said.

Those situations included a 25-year prison sentence. When Dupont was 19, he was convicted of murdering a man who had attacked his brother. “My relationship with Mike before prison was close, and those 40-foot walls did not change that,” he said. Some 20 years into his sentence, in 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo granted him clemency, a decision that prison officials attributed to Dupont’s outstanding work as a youth counselor. Dupont, in turn, credited Williams with helping him become a leader. “Mike fostered those things in me,” he said.

Shortly before Dupont got out, he and Williams made Raised in the System, a documentary for VICE on HBO about America’s mass incarceration of teenagers. In interviews, Williams has said this was a transformative experience, the beginning of a quest to understand and address the root causes of the suffering in his community. It was through this work that he got to know Edwin Raymond, a police lieutenant and activist from East Flatbush. In 2015, Raymond and 11 other Black and brown officers had sued the city, alleging that the NYPD had pressured them to engage in discriminatory practices. Last year, Williams brought Raymond to the Academy Awards. On the red carpet, he declined to speak to any reporter who didn’t interview Raymond first. “He was someone who never forgot the hood,” Raymond said. “He used his influence as much as possible to lift up people beyond him.”

One of those people was Alvin Washington’s son, AJ. Over the past year, AJ, who is 15, has recorded dozens of episodes of a video podcast in his family’s Vanderveer apartment. Called Old2New, it features his conversations with older members of the community — “people who’s been through the street life and in jail, stuff like that,” he told me.

In February, Williams appeared on the show. For a half hour, he answered AJ’s questions with remarkable thoughtfulness and vulnerability. At one point, he observed that people deal with pain and anger in different ways. “For me, I turn my pain inward, and I hurt myself,” he said. Others hurt those around them. “So it’s all about, we gotta love each other no matter what,” he said. “We gotta lift each other up.”

“We should help each other instead of fighting each other,” AJ said, agreeing. “You don’t gotta take each other’s life.”

“You said some valuable words right there, man,” Williams replied. He looked into the distance, gathering his thoughts. “As I get older,” he said, “I start to realize that our inability to communicate with each other as Black men and women — that was on purpose. When they brought us here as slaves, they took away our language, our culture, our spirituality, our religion. They stripped all of that away from us.” He added, “I was made to slit your throat so I could eat.”

As the conversation wound down, AJ told Williams that he looked up to him. “I just want to be like you,” he said with a shy smile. Williams raised his eyebrows and wagged a finger. “Oh no, no, no,” he said. “Do me one favor, nephew. Don’t be like me. Be better than me. Stand on these shoulders and take it higher.” He assured AJ that he was already on his way. “Be great,” he said. “Greater than me. Please. You hear me?”

In the Vanderveer Projects, Michael K. Williams Was Another Kind of Star

By Saki Knafo

Williams at the Vanderveer Estates, where he grew up. Photo: Demetrius Freeman/The New York Times/Redux

The housing project known as Vanderveer Estates consists of 59 red-brick buildings bound by Nostrand and Foster Avenues in East Flatbush, Brooklyn. One night a few months ago, the actor Michael K. Williams stood in front of one of those buildings and gave a speech. “I love my hood,” he said, hoarse with emotion. “I’m born and raised on these streets.” He was wearing a white hooded sweatshirt and white sweatpants, with a white face mask pulled down under his chin, and in the bright lights of the courtyard, he seemed to glow. Scanning the faces in the crowd, he said he had come back home to Vanderveer (or Flatbush Gardens, as it is now officially called) to deliver a message to the neighborhood’s youth. “We can be together,” he insisted. “We can love on each other. It’s possible.”

Williams gave many speeches in recent years, often on the streets of Brooklyn’s Black neighborhoods. As one of the founders of a nonprofit organization called We Build the Block, he presided over a series of unconventional gatherings throughout the borough — block parties where teenage organizers registered their neighbors to vote. He also backed a candidate for City Council, spent hours engaging groups of young people in private conversations, and traveled around the country showing a film he’d made about the incarceration of teenagers to anyone willing to see it — judges, cops, incarcerated teens themselves. When he spoke, he assumed a sort of fighting stance, his shoulders squared and nostrils flared, conveying the same combination of ferocity and tenderness that had defined his portrayal of Omar Little, one of television’s most indelible roles. Back in Vanderveer, some of his old friends called him “the prophet of the projects,” and it wasn’t hard to see why. With the white beard he sometimes wore, his intense gaze, and his fierce appeals for justice and love, he could put you in mind of the holy men of the Bible.

On Monday, Williams was found dead of a suspected overdose in his Williamsburg apartment. He was 54. This week, as the world mourned the loss of a great actor, people in Flatbush grappled with the loss of something greater. His friends and family remembered him as a rare kind of person, someone from a very hard place with a very soft heart. “Mike believed that it was important to be loved and to feel love,” his nephew Dominic Dupont said. “He showed that through how he treated people.”

Williams lived in Vanderveer until he filmed the second season of The Wire. His building overlooked a courtyard known as the Terrace. “We called ourselves Terrace Massive,” Alvin Washington, a childhood friend, recalled. “It was about 15 of us. A little crew.” Of those 15 or so friends, nearly half have died. According to Washington, only Williams and maybe one other boy avoided doing time. “Mike will tell you in three seconds, he’s not a gangster,” he said, laughing. “He was a free soul. If he felt like dancing, he danced. If he felt like crying, he cried.”

Washington was serving an eight-year sentence for robbery when The Wire came out. He and the other men in his cellblock would crowd into the day room to watch it. “Ain’t no talking when it was on,” he said. When he got out of jail, Williams gave him a box set of the series and a collection of designer clothes that people had sent him. He took him to parties and introduced him to celebrities. “I know mad people who come from where he came from and don’t pick nobody up,” Washington said. “They just brush you off, because you might still be a criminal or something, but Mike looked past that and saw the person.” Recently, Williams started a production company, Freedome, with the goal of producing work by local Black artists. He planned to cast people from the community in minor roles. “Everybody would get to eat off of it,” Washington said, “because that’s how he designed it.”

Dupont, Williams’s nephew, said he believed Williams’s vision for the company would still come to fruition. “We will continue to move forward in a direction that’s consistent with Michael’s vision for the world,” he told me. He was speaking on the phone from Williams’s apartment in Williamsburg, where, two days earlier, he had found his uncle’s body. He said the love that Williams had shown him throughout his life had, in a strange way, enabled him to get through that moment. “He helped prepare me to deal with tough situations,” he said.

Those situations included a 25-year prison sentence. When Dupont was 19, he was convicted of murdering a man who had attacked his brother. “My relationship with Mike before prison was close, and those 40-foot walls did not change that,” he said. Some 20 years into his sentence, in 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo granted him clemency, a decision that prison officials attributed to Dupont’s outstanding work as a youth counselor. Dupont, in turn, credited Williams with helping him become a leader. “Mike fostered those things in me,” he said.

Shortly before Dupont got out, he and Williams made Raised in the System, a documentary for VICE on HBO about America’s mass incarceration of teenagers. In interviews, Williams has said this was a transformative experience, the beginning of a quest to understand and address the root causes of the suffering in his community. It was through this work that he got to know Edwin Raymond, a police lieutenant and activist from East Flatbush. In 2015, Raymond and 11 other Black and brown officers had sued the city, alleging that the NYPD had pressured them to engage in discriminatory practices. Last year, Williams brought Raymond to the Academy Awards. On the red carpet, he declined to speak to any reporter who didn’t interview Raymond first. “He was someone who never forgot the hood,” Raymond said. “He used his influence as much as possible to lift up people beyond him.”

One of those people was Alvin Washington’s son, AJ. Over the past year, AJ, who is 15, has recorded dozens of episodes of a video podcast in his family’s Vanderveer apartment. Called Old2New, it features his conversations with older members of the community — “people who’s been through the street life and in jail, stuff like that,” he told me.

In February, Williams appeared on the show. For a half hour, he answered AJ’s questions with remarkable thoughtfulness and vulnerability. At one point, he observed that people deal with pain and anger in different ways. “For me, I turn my pain inward, and I hurt myself,” he said. Others hurt those around them. “So it’s all about, we gotta love each other no matter what,” he said. “We gotta lift each other up.”

“We should help each other instead of fighting each other,” AJ said, agreeing. “You don’t gotta take each other’s life.”

“You said some valuable words right there, man,” Williams replied. He looked into the distance, gathering his thoughts. “As I get older,” he said, “I start to realize that our inability to communicate with each other as Black men and women — that was on purpose. When they brought us here as slaves, they took away our language, our culture, our spirituality, our religion. They stripped all of that away from us.” He added, “I was made to slit your throat so I could eat.”

As the conversation wound down, AJ told Williams that he looked up to him. “I just want to be like you,” he said with a shy smile. Williams raised his eyebrows and wagged a finger. “Oh no, no, no,” he said. “Do me one favor, nephew. Don’t be like me. Be better than me. Stand on these shoulders and take it higher.” He assured AJ that he was already on his way. “Be great,” he said. “Greater than me. Please. You hear me?”

This was a good dude man...he had a lot to live for but his demons got him

‘Last Week Tonight With John Oliver’ Pays Tribute To Michael K. Williams & Producer Amanda Bayard

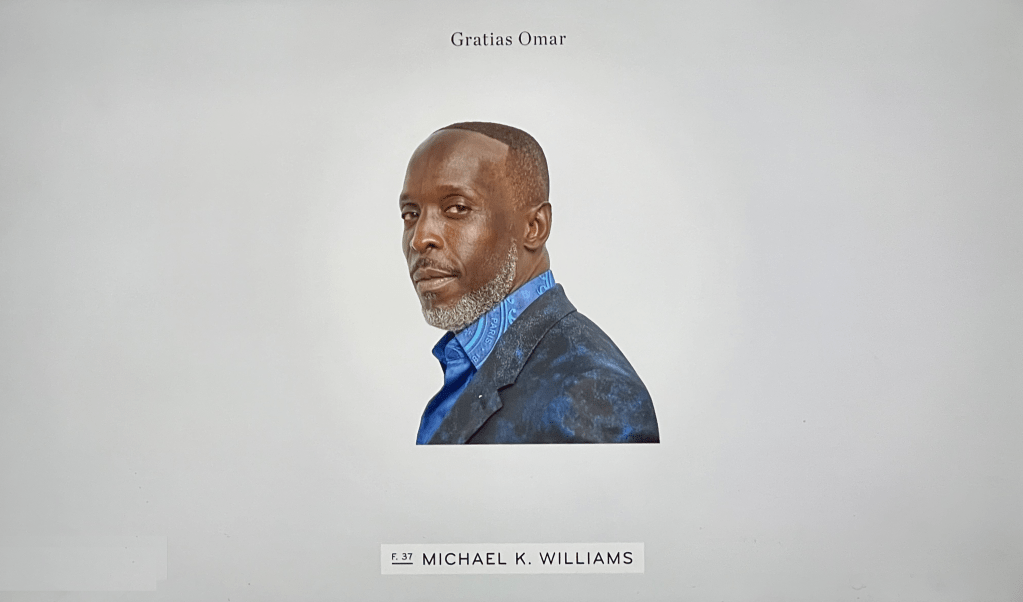

HBO’s Last Week Tonight With John Oliver on Sunday honored Emmy-nominated actor Michael K. Williams who died Sept. 6 at the age of 54. The show’s Latin-themed opening montage featured a photo of Williams and a note, “Gratias Omar”, “Thank you” in Latin and a reference to Williams’ signature role...

Emmy Winner Courtney B. Vance Pays Tribute To ‘Lovecraft Country’s Michael K. Williams; Says HBO Show’s Cancellation “Doesn’t Make Sense”

Courtney B. Vance Pays Tribute To 'Lovecraft Country' Co-Star Michael K. Williams: "Let Us All Honor His Immense Legacy"

Emmy Winner Courtney B. Vance Pays Tribute To ‘Lovecraft Country’s Michael K. Williams; Says HBO Show’s Cancellation “Doesn’t Make Sense”

Courtney B. Vance Pays Tribute To 'Lovecraft Country' Co-Star Michael K. Williams: "Let Us All Honor His Immense Legacy"

Emmy Winner Courtney B. Vance Pays Tribute To ‘Lovecraft Country’s Michael K. Williams; Says HBO Show’s Cancellation “Doesn’t Make Sense”

By Antonia Blyth

On Sunday, Courtney B. Vance accepted his guest actor Emmy Award for Lovecraft Country, and took the opportunity to pay touching tribute to his recently passed co-star Michael K. Williams.

After thanking creator Misha Green, the show, his fellow nominees, fans and his wife and children, Vance said, “Finally to Michael K. Williams. Misha said it best. Michael did everything with his full heart open, with his infinite spirit and with way too much style. May he rest in power and let us all honor his immense legacy by being a little more love forward, a little more endless in thought and a little more swaggy in act.”

Speaking backstage after his win, Vance said, “I love him. We recently met for the first time. I’ve been following him and he’s been following me for a number of years. We met at an event in New Jersey about two and-a-half, three years ago. We were just overjoyed to share the dame dias and couldn’t wait to get offstage so we could hug and just say how much we loved each other. And the idea that shortly after that we would be playing brothers in Lovecraft Country. This is his. We were brothers. I died in the series and we said goodbye to each other, so it’s just too painful to really think about so I just honor him everywhere and every way I can.”

Vance is not the first to pay tribute while accepting an Emmy for this show. On Saturday, during the first Creative Arts Emmy ceremony, leading Sound Supervisor Tim Kimmel honored Williams in his acceptance speech.

Williams, perhaps best known for his role of Omar on The Wire, died September 6 in Brooklyn. He was 54. Williams is up for a Supporting Actor Emmy this year was for his portrayal of Lovecraft Country‘s Montrose Freeman.

Vance’s win was so far the second for Lovecraft Country. It landed 18 nominations total, following its cancellation by HBO. Speaking about what the win meant to him, Vance said,

“I’m very, very happy and at the same time I’m very sad because of Michael and because we’re not still doing the show. In my mind and in my spirit it doesn’t make sense… I’m sad for audiences that we don’t get to see like Game of Thrones we don’t get to see seven years, eight years of following these characters and learning more about that time period and learning about our people and their struggles. And where Misha’s mind is going to go so that’s very painful for me as an actor.”

Despite being cancelled, Lovecraft made history by having Black nominees in every acting category. “I don’t understand it [the cancellation],” Vance continued. “it doesn’t make sense to fans and that’s all who matter. We set everyone up and then we don’t deliver for whatever reason. I’m tired of it…they can find a way to make a Game of Thrones, but not Lovecraft Country.”

Last edited:

In the Vanderveer Projects, Michael K. Williams Was Another Kind of Star

By Saki Knafo

Williams at the Vanderveer Estates, where he grew up. Photo: Demetrius Freeman/The New York Times/Redux

The housing project known as Vanderveer Estates consists of 59 red-brick buildings bound by Nostrand and Foster Avenues in East Flatbush, Brooklyn. One night a few months ago, the actor Michael K. Williams stood in front of one of those buildings and gave a speech. “I love my hood,” he said, hoarse with emotion. “I’m born and raised on these streets.” He was wearing a white hooded sweatshirt and white sweatpants, with a white face mask pulled down under his chin, and in the bright lights of the courtyard, he seemed to glow. Scanning the faces in the crowd, he said he had come back home to Vanderveer (or Flatbush Gardens, as it is now officially called) to deliver a message to the neighborhood’s youth. “We can be together,” he insisted. “We can love on each other. It’s possible.”

Williams gave many speeches in recent years, often on the streets of Brooklyn’s Black neighborhoods. As one of the founders of a nonprofit organization called We Build the Block, he presided over a series of unconventional gatherings throughout the borough — block parties where teenage organizers registered their neighbors to vote. He also backed a candidate for City Council, spent hours engaging groups of young people in private conversations, and traveled around the country showing a film he’d made about the incarceration of teenagers to anyone willing to see it — judges, cops, incarcerated teens themselves. When he spoke, he assumed a sort of fighting stance, his shoulders squared and nostrils flared, conveying the same combination of ferocity and tenderness that had defined his portrayal of Omar Little, one of television’s most indelible roles. Back in Vanderveer, some of his old friends called him “the prophet of the projects,” and it wasn’t hard to see why. With the white beard he sometimes wore, his intense gaze, and his fierce appeals for justice and love, he could put you in mind of the holy men of the Bible.

On Monday, Williams was found dead of a suspected overdose in his Williamsburg apartment. He was 54. This week, as the world mourned the loss of a great actor, people in Flatbush grappled with the loss of something greater. His friends and family remembered him as a rare kind of person, someone from a very hard place with a very soft heart. “Mike believed that it was important to be loved and to feel love,” his nephew Dominic Dupont said. “He showed that through how he treated people.”

Williams lived in Vanderveer until he filmed the second season of The Wire. His building overlooked a courtyard known as the Terrace. “We called ourselves Terrace Massive,” Alvin Washington, a childhood friend, recalled. “It was about 15 of us. A little crew.” Of those 15 or so friends, nearly half have died. According to Washington, only Williams and maybe one other boy avoided doing time. “Mike will tell you in three seconds, he’s not a gangster,” he said, laughing. “He was a free soul. If he felt like dancing, he danced. If he felt like crying, he cried.”

Washington was serving an eight-year sentence for robbery when The Wire came out. He and the other men in his cellblock would crowd into the day room to watch it. “Ain’t no talking when it was on,” he said. When he got out of jail, Williams gave him a box set of the series and a collection of designer clothes that people had sent him. He took him to parties and introduced him to celebrities. “I know mad people who come from where he came from and don’t pick nobody up,” Washington said. “They just brush you off, because you might still be a criminal or something, but Mike looked past that and saw the person.” Recently, Williams started a production company, Freedome, with the goal of producing work by local Black artists. He planned to cast people from the community in minor roles. “Everybody would get to eat off of it,” Washington said, “because that’s how he designed it.”

Dupont, Williams’s nephew, said he believed Williams’s vision for the company would still come to fruition. “We will continue to move forward in a direction that’s consistent with Michael’s vision for the world,” he told me. He was speaking on the phone from Williams’s apartment in Williamsburg, where, two days earlier, he had found his uncle’s body. He said the love that Williams had shown him throughout his life had, in a strange way, enabled him to get through that moment. “He helped prepare me to deal with tough situations,” he said.

Those situations included a 25-year prison sentence. When Dupont was 19, he was convicted of murdering a man who had attacked his brother. “My relationship with Mike before prison was close, and those 40-foot walls did not change that,” he said. Some 20 years into his sentence, in 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo granted him clemency, a decision that prison officials attributed to Dupont’s outstanding work as a youth counselor. Dupont, in turn, credited Williams with helping him become a leader. “Mike fostered those things in me,” he said.

Shortly before Dupont got out, he and Williams made Raised in the System, a documentary for VICE on HBO about America’s mass incarceration of teenagers. In interviews, Williams has said this was a transformative experience, the beginning of a quest to understand and address the root causes of the suffering in his community. It was through this work that he got to know Edwin Raymond, a police lieutenant and activist from East Flatbush. In 2015, Raymond and 11 other Black and brown officers had sued the city, alleging that the NYPD had pressured them to engage in discriminatory practices. Last year, Williams brought Raymond to the Academy Awards. On the red carpet, he declined to speak to any reporter who didn’t interview Raymond first. “He was someone who never forgot the hood,” Raymond said. “He used his influence as much as possible to lift up people beyond him.”

One of those people was Alvin Washington’s son, AJ. Over the past year, AJ, who is 15, has recorded dozens of episodes of a video podcast in his family’s Vanderveer apartment. Called Old2New, it features his conversations with older members of the community — “people who’s been through the street life and in jail, stuff like that,” he told me.

In February, Williams appeared on the show. For a half hour, he answered AJ’s questions with remarkable thoughtfulness and vulnerability. At one point, he observed that people deal with pain and anger in different ways. “For me, I turn my pain inward, and I hurt myself,” he said. Others hurt those around them. “So it’s all about, we gotta love each other no matter what,” he said. “We gotta lift each other up.”

“We should help each other instead of fighting each other,” AJ said, agreeing. “You don’t gotta take each other’s life.”

“You said some valuable words right there, man,” Williams replied. He looked into the distance, gathering his thoughts. “As I get older,” he said, “I start to realize that our inability to communicate with each other as Black men and women — that was on purpose. When they brought us here as slaves, they took away our language, our culture, our spirituality, our religion. They stripped all of that away from us.” He added, “I was made to slit your throat so I could eat.”

As the conversation wound down, AJ told Williams that he looked up to him. “I just want to be like you,” he said with a shy smile. Williams raised his eyebrows and wagged a finger. “Oh no, no, no,” he said. “Do me one favor, nephew. Don’t be like me. Be better than me. Stand on these shoulders and take it higher.” He assured AJ that he was already on his way. “Be great,” he said. “Greater than me. Please. You hear me?”

Just saw this. Aw man. Damn

RIP

Bro was funny too!

But this "Typecast"is him (to me).

"Are you sure about that?"

Bro was funny too!

But this "Typecast"is him (to me).

"Are you sure about that?"

Michael K. Williams gettin' a surprised birthday cake on the set of Love Craft Country......

Jurnee Smollett Honors Michael K. Williams In Heartfelt Tribute

Smollett, who recently starred alongside Williams in HBO’s Lovecraft Country, penned the touching post hours after he was laid to rest on Tuesday.

www.theroot.com

www.theroot.com

Michael K. Williams Was A Chronicler of Black Humanity

To be a Black artist means to be an archivist of our existence; Michael K. Williams excelled in this role.

www.theroot.com

www.theroot.com

Jonathan Majors Pens Touching Tribute to Michael K. Williams

Majors recently starred alongside Williams in the multiple Emmy-nominated HBO series Lovecraft Country.

www.theroot.com

www.theroot.com

Michael Kenneth Williams Was a Master of Blending In While Standing Out

Every TV fan knew Michael Kenneth Williams. But when it came to each new role, that never stopped him from making us forget.

Michael K. Williams Laid to Rest in Private Pennsylvania Funeral

Michael K. Williams was found dead in his Brooklyn apartment on Sep. 6

Michael K. Williams laid to rest, remembered by Jurnee Smollett: 'Still can't make sense of it'

Michael K. Williams was laid to rest Tuesday. Hours later, his "Lovecraft Country" co-star Jurnee Smollett shared a heartbreaking tribute.

www.usatoday.com

Emmys: Michael K. Williams’ Nephew Will Accept if ‘Lovecraft Country’ Star Wins (Exclusive)

Dominic Dupont was the subject of a Vice documentary for which Williams received one of his four prior Emmy nominations.

Alan Pergament: Recalling an old, chilling interview with Michael K. Williams of 'The Wire'

The actor, 54, was found dead on Sept. 6 in Brooklyn.

your working your ass off to troll. What is sad is the fact that is a part of your DNA and there is nothing you can do about it.kids, dont do drugs.

then go do drugsyour working your ass off to troll. What is sad is the fact that is a part of your DNA and there is nothing you can do about it.

Eddie Murphy made a joke back in 1983, saying how people would say he will get on drugs in the industry. He was like "not me baby"... Now all the people in that mid 80s class Michael Jackson, Prince, Whitney Houston, are all gone through the use of drugs. Fame doesn't equate to happiness.

Who's ever idea that was needs a fucking raise

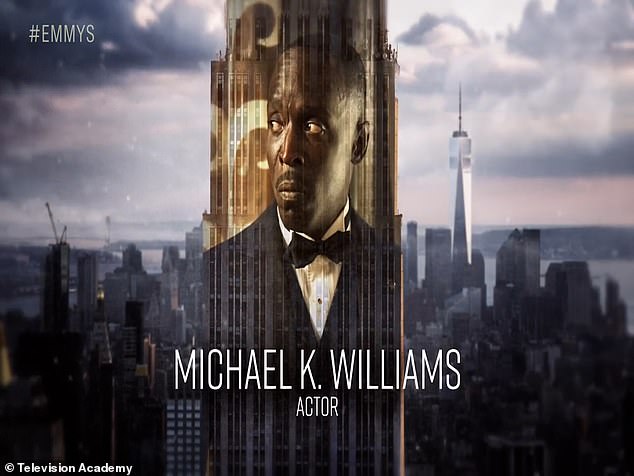

The Wire's Michael K. Williams and Up's Ed Asner honoured at Emmys

Michael K. Williams, Cicely Tyson, and Ed Asner were among those remembered during the Primetime Emmy Awards' annual In Memoriam segment on Sunday.

Baltimore Ravens salute Michael K. Williams with 'The Wire' whistle

The Baltimore Ravens kicked off their game Sunday with a tribute to Michael K. Williams, playing the famous whistle of Omar Little, the late actor's Baltimore-based character on 'The Wire.'

god dammit ...2 wks later ..

i know i shouldnt have watched this shit ...dam u funk ...

Michael K. Williams Died of a Drug Overdose, Authorities Say

The actor known for “The Wire,” who was found dead in his apartment earlier this month, died of intoxication by a mixture of heroin, cocaine and fentanyl. He had been open about his struggle with addiction.

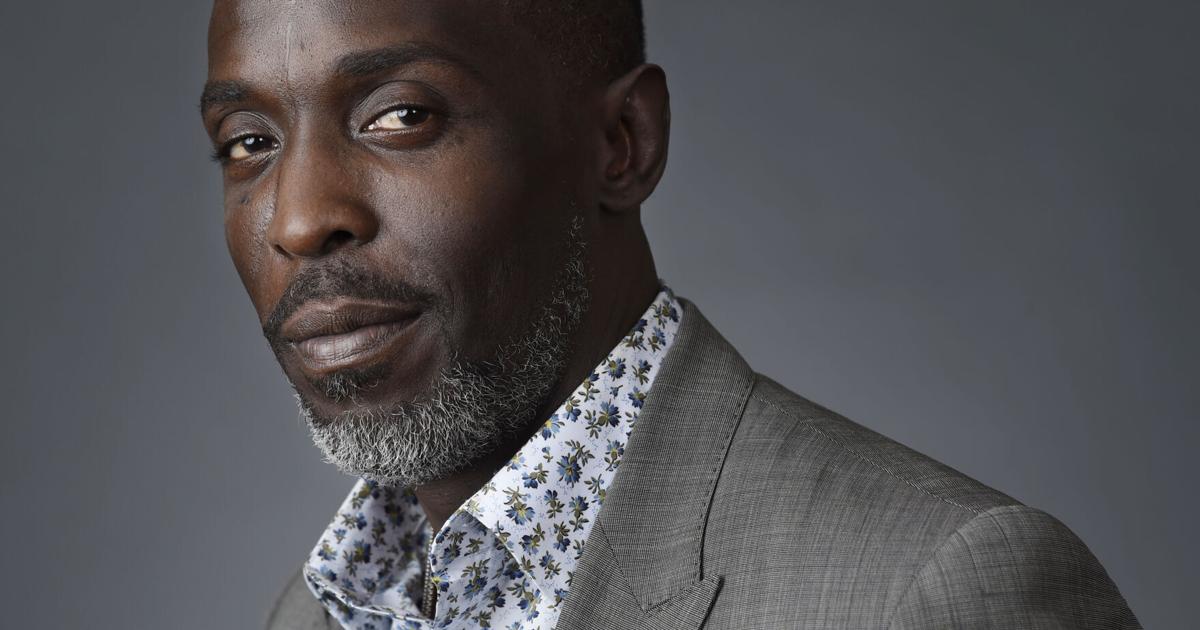

Michael K. Williams lived much of his life in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.Credit...Arturo Holmes/Getty Images For Aba

By Michael Gold and Jonah E. Bromwich

Sept. 24, 2021Updated 7:00 p.m. ET

The death this month of Michael K. Williams, the Brooklyn actor most famous for his memorable portrayal of a gay stickup man in “The Wire,” was caused by an accidental drug overdose involving fentanyl, New York City’s medical examiner said on Friday.

Mr. Williams, 54, was found dead in his apartment in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn on Sept. 6. The medical examiner said the official cause of death was “acute intoxication by the combined effects of fentanyl, p-fluorofentanyl, heroin and cocaine.”

A longtime representative for Mr. Williams did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The presence of multiple drugs in Mr. Williams’s system at the time of his death does not necessarily indicate whether he took those drugs together or separately, or whether he used them knowingly or unknowingly.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that can be 50 times more powerful than heroin and is cheaper to produce and distribute, has seen increased use in the United States in recent years as an alternative to heroin or prescription opioids. It has also contributed to a rise in fatal overdoses among older people and African-Americans.

Though it is common for heroin to be mixed with fentanyl, the combination of cocaine and fentanyl recently drew attention after eight people overdosed on Long Island after taking the two drugs. Six of those overdoses were fatal.

It is impossible to know which of the drugs found in Mr. Williams system caused his death, or whether a lethal combination was to blame, but fentanyl adulteration in both heroin and cocaine is a growing threat.

Before his death, Mr. Williams — most known for his role on a show that tackled drugs, addiction, corruption and the police — had openly discussed his struggles with drug addiction in interviews.

In 2016, he told NPR’s Terry Gross that he had started doing drugs during the second or third season of “The Wire,” the beloved HBO series in which he played Omar Little, a principled thief who specialized in robbing drug dealers and who former President Barack Obama once said at a campaign rally was his favorite character on television.

Mr. Williams met Mr. Obama, then a senator, at that rally in 2008. Mr. Williams told The New York Times in 2017 that he was high at the time and could barely talk. Hearing Mr. Obama compliment his work, he said, “woke me up.”

According to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, drug overdoses have risen in the United States during the pandemic. In 2020, more than 93,000 people overdosed, an increase of nearly 30 percent over the previous year.

New York City experienced a record-breaking rise in such deaths, with more than 1,600 people dying over the course of the year and about five dying every day, according to the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City of New York. The vast majority of those deaths involved fentanyl.

Mr. Williams grew up in Brooklyn’s East Flatbush neighborhood and maintained significant ties to the community even as his career drew him away. Residents there said they were devastated by his death.

For years, Mr. Williams participated in youth-focused events or food drives for the hungry. He was a vocal advocate for criminal justice reform and ending mass incarceration.

But his connections to his roots came in less tangible ways too: he said that he constantly drew inspiration for his characters from people in the neighborhood.

Beyond “The Wire,” Mr. Williams acted in acclaimed series like “Boardwalk Empire,” “The Night Of” and “When They See Us,” a mini-series about the five Black and Latino teenagers wrongfully convicted in the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park. (Mr. Williams was in his 20s and living in New York City when the trial took place and said he felt a complicated connection to it.)

He received five Emmy Award nominations over his career, including one this year for supporting actor in a drama series for his role in “Lovecraft County.”

At the ceremony, held on Sunday, the actress Kerry Washington paused to pay tribute to Mr. Williams before presenting the award in his category. She described him as “a brilliantly talented actor and a generous human being.”

Ms. Washington then addressed Mr. Williams: “Michael, I know you’re here, because you wouldn’t miss this. Your excellence, your artistry will endure. We love you.”

The actor known for “The Wire,” who was found dead in his apartment earlier this month, died of intoxication by a mixture of heroin, cocaine and fentanyl. He had been open about his struggle with addiction.

Michael K. Williams lived much of his life in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.Credit...Arturo Holmes/Getty Images For Aba

By Michael Gold and Jonah E. Bromwich

Sept. 24, 2021Updated 7:00 p.m. ET

The death this month of Michael K. Williams, the Brooklyn actor most famous for his memorable portrayal of a gay stickup man in “The Wire,” was caused by an accidental drug overdose involving fentanyl, New York City’s medical examiner said on Friday.

Mr. Williams, 54, was found dead in his apartment in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn on Sept. 6. The medical examiner said the official cause of death was “acute intoxication by the combined effects of fentanyl, p-fluorofentanyl, heroin and cocaine.”

A longtime representative for Mr. Williams did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The presence of multiple drugs in Mr. Williams’s system at the time of his death does not necessarily indicate whether he took those drugs together or separately, or whether he used them knowingly or unknowingly.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that can be 50 times more powerful than heroin and is cheaper to produce and distribute, has seen increased use in the United States in recent years as an alternative to heroin or prescription opioids. It has also contributed to a rise in fatal overdoses among older people and African-Americans.

Though it is common for heroin to be mixed with fentanyl, the combination of cocaine and fentanyl recently drew attention after eight people overdosed on Long Island after taking the two drugs. Six of those overdoses were fatal.

It is impossible to know which of the drugs found in Mr. Williams system caused his death, or whether a lethal combination was to blame, but fentanyl adulteration in both heroin and cocaine is a growing threat.

Before his death, Mr. Williams — most known for his role on a show that tackled drugs, addiction, corruption and the police — had openly discussed his struggles with drug addiction in interviews.

In 2016, he told NPR’s Terry Gross that he had started doing drugs during the second or third season of “The Wire,” the beloved HBO series in which he played Omar Little, a principled thief who specialized in robbing drug dealers and who former President Barack Obama once said at a campaign rally was his favorite character on television.

Mr. Williams met Mr. Obama, then a senator, at that rally in 2008. Mr. Williams told The New York Times in 2017 that he was high at the time and could barely talk. Hearing Mr. Obama compliment his work, he said, “woke me up.”

According to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, drug overdoses have risen in the United States during the pandemic. In 2020, more than 93,000 people overdosed, an increase of nearly 30 percent over the previous year.

New York City experienced a record-breaking rise in such deaths, with more than 1,600 people dying over the course of the year and about five dying every day, according to the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City of New York. The vast majority of those deaths involved fentanyl.

Mr. Williams grew up in Brooklyn’s East Flatbush neighborhood and maintained significant ties to the community even as his career drew him away. Residents there said they were devastated by his death.

For years, Mr. Williams participated in youth-focused events or food drives for the hungry. He was a vocal advocate for criminal justice reform and ending mass incarceration.

But his connections to his roots came in less tangible ways too: he said that he constantly drew inspiration for his characters from people in the neighborhood.

Beyond “The Wire,” Mr. Williams acted in acclaimed series like “Boardwalk Empire,” “The Night Of” and “When They See Us,” a mini-series about the five Black and Latino teenagers wrongfully convicted in the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park. (Mr. Williams was in his 20s and living in New York City when the trial took place and said he felt a complicated connection to it.)

He received five Emmy Award nominations over his career, including one this year for supporting actor in a drama series for his role in “Lovecraft County.”

At the ceremony, held on Sunday, the actress Kerry Washington paused to pay tribute to Mr. Williams before presenting the award in his category. She described him as “a brilliantly talented actor and a generous human being.”

Ms. Washington then addressed Mr. Williams: “Michael, I know you’re here, because you wouldn’t miss this. Your excellence, your artistry will endure. We love you.”

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 525

- Replies

- 34

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 72

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 97