This past Saturday, about a dozen people from across the United States and Canada held a Zoom memorial for a man whose remains have been lying in an unmarked grave in Nova Scotia since last spring.

He was Charles R. Saunders, and his lonely death in May belied his status as a foundational figure in a literary genre known as sword and soul. Some 40 years ago, Mr. Saunders reimagined the white worlds of Tarzan and Conan with Black heroes and African mythologies in books that spoke especially to Black fans eager for more fictional champions with whom they could identify.

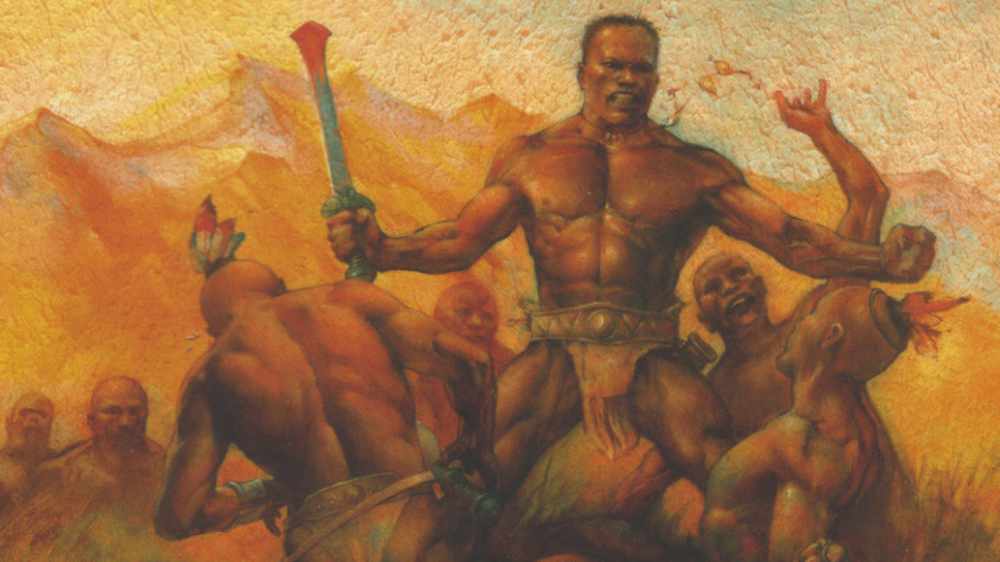

Some of those on the Zoom call knew Mr. Saunders as a copy editor and writer for The Daily News of Halifax, a newspaper that went under in 2008. One first met him in the 1970s, when he was teaching at Algonquin College in Ontario. Most had been profoundly influenced by his fiction, especially his book series that features a warrior hero named Imaro, who battles enemies both human and supernatural and does it as part of a rich, vibrant Black civilization that contrasted sharply with the “Dark Continent” view of Africa that had long been served up by white writers.

All of them wanted, by the small gesture of the Zoom memorial and larger gestures yet to come, to make sure that Mr. Saunders’s death did not go unnoticed, and that his contributions do not go unremembered.

“Charles gave us that fictional hero that looked like us and existed in a world based on our origins,” Milton J. Davis, a Black writer of speculative fiction who acted as host of the Zoom memorial, said by email the next day. “He did it without using the ‘struggle’ narrative that traditional publishers seem to require from Black authors. Imaro’s struggles and triumphs were personal, not ‘racial,’ which for me was a breath of fresh air.”

Taaq Kirksey, another organizer of the memorial, first became enamored of Mr. Saunders’s fiction in 2004 while in his final semester at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and ever since he has been working to turn the Imaro stories into a movie or television series, an effort he said is close to bearing fruit.

Mr. Kirksey had corresponded with the reclusive Mr. Saunders on and off for years but had met him face to face only once, in June 2019, when he traveled to Nova Scotia and presented him with his first check from their long-simmering collaboration.

“I had always been afraid that his living situation was suboptimal,” Mr. Kirksey said, “and when I got up there to see him, those fears were validated.”

Mr. Saunders’s health was not good; he had diabetes, among other problems.

“My instinct told me he didn’t have much time,” Mr. Kirksey said.

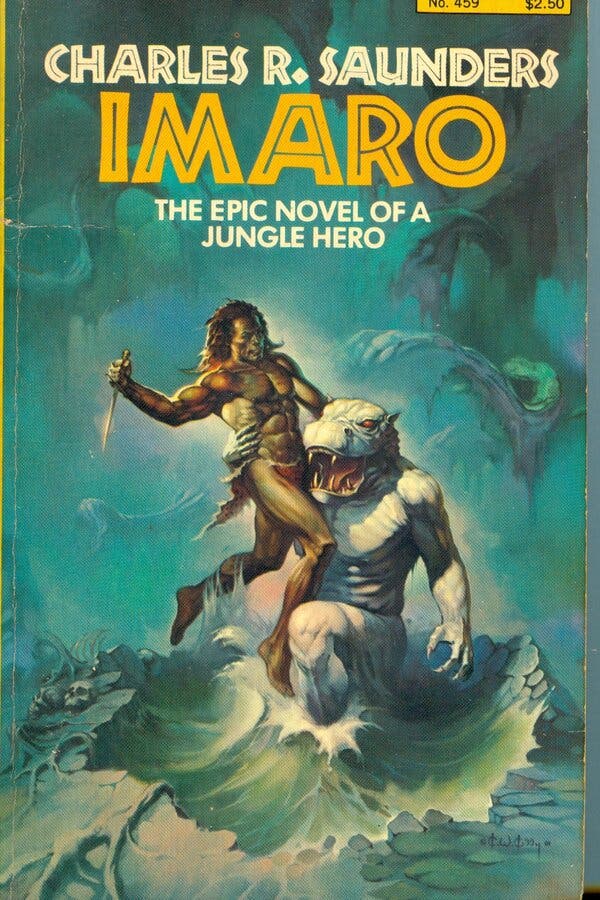

Image

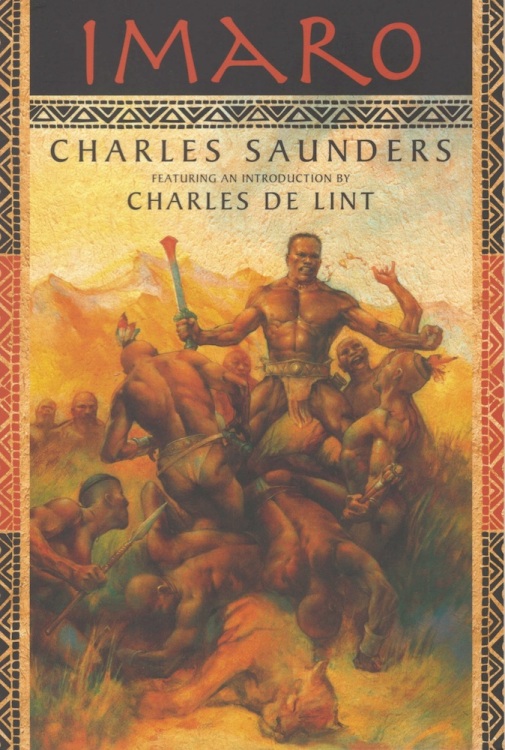

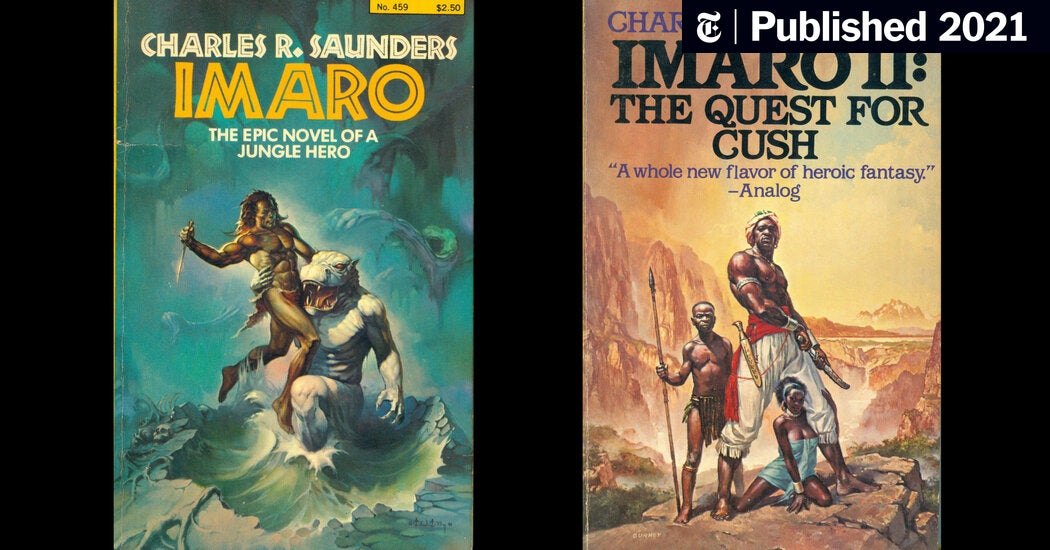

Mr. Saunders began writing speculative fiction in the 1970s and published his first novel, “Imaro,” in 1981.Credit...via Taaq Kirksey

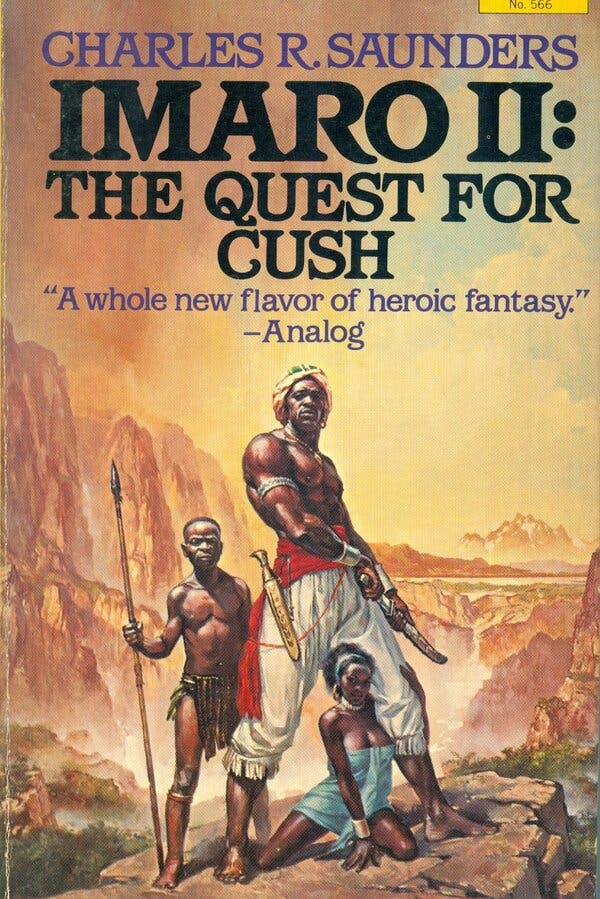

Image

“Imaro II: The Quest for Cush” was published in 1984. The Imaro books, Mr. Kirksey said, reclaimed a continent and a heritage for Black readers.Credit...via Taaq Kirksey

Mr. Saunders had no phone or internet service, and was in the habit of going to the local library once a week or so to keep up with friends by email. Early last year, when Covid-19 caused the province to lock down, his access to the library was cut off. Another long-distance friend, Dale Armelin, who lives in Colorado, became concerned when Mr. Saunders’s emails stopped. In early May he asked local officials to check on his friend at his apartment in the Dartmouth section of Halifax. He was fine.

But then, as Mr. Kirksey put it, “somewhere between May 2 and May 15, he wasn’t fine” — a crew doing work on Mr. Saunders’s apartment building found him dead. The cause wasn’t clear. He was 73.

Mr. Armelin eventually got a call from Nova Scotia officials, who told him that they had his name only because of his request for a wellness check. The officials could find no local friends or relatives. When a body goes unclaimed in the province, the office of the Public Trustee of Nova Scotia takes over. It arranged for Mr. Saunders to be buried on a hillside in Dartmouth Memorial Gardens.

Jon Tattrie, a journalist who had worked with Mr. Saunders for two years at The Daily News, pieced together what had happened in

an article published by CBC News in September.

“By law,”

he wrote, “the public purse covers the cost of the plot, and of the burial. But it doesn’t cover a headstone.”

And so Mr. Tattrie and others, including Mr. Kirksey and Mr. Davis, created a

GoFundMe page to raise money for a headstone as well as a stone monument representing Imaro, Mr. Saunders’s best-known fictional creation. They will be installed in the next few months, Mr. Tattrie said during the Zoom memorial, and he hopes to organize a graveside service in May around the anniversary of the death.

It fell to Mr. Kirksey to put together a sparse biography of Mr. Saunders for the Zoom memorial.

Charles Robert Saunders was born on July 3, 1946, in Elizabeth, Pa., near Pittsburgh, and grew up there and in Norristown, Pa. In 1968 he earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology at Lincoln University, west of Philadelphia.

The next year, he moved to Canada to avoid the draft and became a teacher. At the Zoom memorial, Janet LeRoy recalled the first time she saw him, when she was a student at Carleton University in Ontario in the 1970s and glimpsed him through a doorway, talking to his students. His physical stature — he was 6-foot-4 or so — made a distinct impression, as did his Afro and dashiki top.

“He looked like he’d stepped off the TV show ‘The Mod Squad,’” she said.

Three years later, she finally met him when they were both teaching at Algonquin College. They became fast friends.

“He was a giant of a man, but he had such a tender, quiet voice,” she said. “We could talk about the deepest, darkest moments in our lives, and Charles would find a way to say something that would make us both chuckle.”

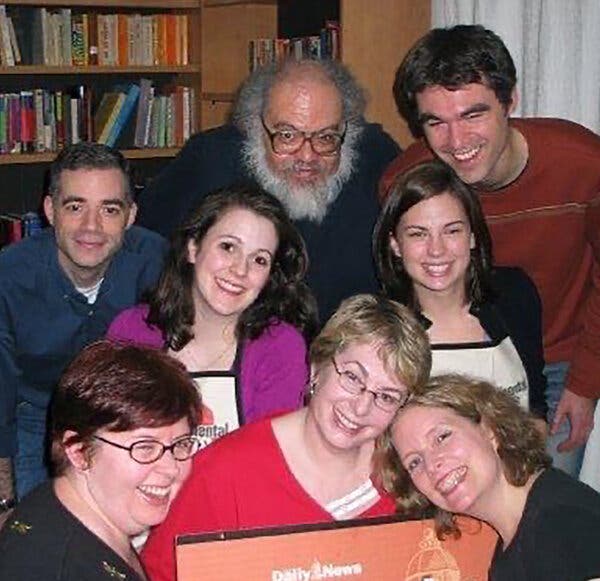

At some point Mr. Saunders moved to Nova Scotia, and in 1989 he began working at The Daily News, editing and sometimes writing, including about issues facing the Black community there.

“He was so quiet,” Mr. Tattrie, speaking at the Zoom memorial, recalled of his presence in the newsroom. “He would never draw attention to himself. But you noticed him. You could just tell there was a depth to him, a richness, that you don’t find in many other people.”

Mr. Saunders in 2008 with colleagues from the staff of The Daily News of Halifax, Nova Scotia, shortly after it shut down. He had been a copy editor and writer there since 1989.Credit...via Jon Tattrie

He was so good at not calling attention to himself that many at the newspaper didn’t realize that he had a whole other life as an author of speculative fiction, the umbrella genre that encompasses fantasy, science fiction and other strains of literature that deal in imagined worlds.

He had begun writing speculative fiction in the 1970s and published his first novel, “Imaro,” in 1981. As a child he had been enthralled by the fantasies spun by white writers like Robert E. Howard, who created Conan the Barbarian, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, who created Tarzan, the white African figure embodied most famously on the screen by Johnny Weissmuller. But he came to recognize the racism inherent in such works. Imaro was the result.

“I think he was born when I watched a Tarzan movie and fantasized a Black man jumping up and beating the hell out of Johnny Weissmuller,” Mr. Saunders told the journal Black American Literature Forum in 1984.

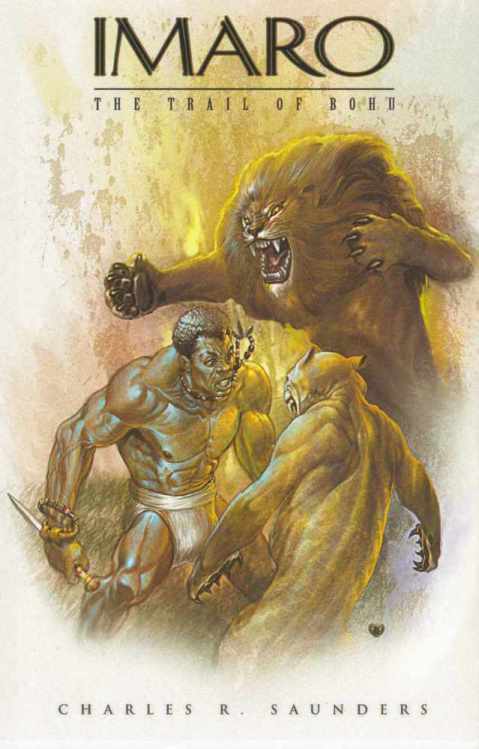

“Imaro II: The Quest for Cush” appeared in 1984, and “Imaro III: The Trail of Bohu” came out the next year. The books, Mr. Kirksey said, reclaimed a continent and a heritage for Black readers.

“For Tarzan to be the king of mythical Africa,” he said, “it’s an utter slap in the face to a young Black child who is looking for a place in his imagination where he can be indomitable, where he can be the king or the queen.”

Though Marvel Comics had introduced the character Black Panther and other Black heroes in its comics before Mr. Saunders’s “Imaro” books, only more recently have Black heroes and Black worlds become more common on bookshelves and on the big and small screens. The hit 2018 film “Black Panther” won three Oscars. Mr. Kirksey said that overdue progress rests in part on Mr. Saunders’s shoulders.

“It’s easy to look at the success of the movie ‘Black Panther’ and think that was always there,” he said. “That’s a very short memory speaking. Charles set that in motion in his own quiet way.”

Mr. Armelin said that though he had never met Mr. Saunders in person, “I consider him my best friend.” The two began corresponding in the mid-1970s, after Mr. Saunders had reached out when he saw a letter Mr. Armelin had written to Marvel commending the company for removing racist elements from a Conan tale it had republished.

During the Zoom memorial, Mr. Armelin confessed that, as a Black youth at an almost all-white Roman Catholic high school, he had “become an Uncle Tom.” Mr. Saunders, through his stories and his counsel, led him to embrace his heritage.

“What Charles did was, he gave me back my Blackness,” he said.

Mr. Kirksey said he believed that Mr. Saunders had married twice and that the marriages had ended in divorce. Whether he has any survivors remains unclear.

But his stories remain. Mr. Saunders created other fantasy worlds in books like “Abengoni,” published by Mr. Davis’s

MVmedia in 2014. In the 1984 interview, he said that the possibilities for Imaro and the other characters who populated his imagination were endless.

“There is so much source material available on African culture and folklore,” he said, “that I would have to live indefinitely to do justice to it all.”

His speculative fiction was built on Black heroes and African themes. He died alone and unrecognized, but friends are trying to make amends.

www.nytimes.com

www.nytimes.com

www.nytimes.com

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org