Raised during the tumult of the civil rights movement, when she was ostracized by White classmates at schools in Georgia and Illinois, Dr. Edelin went into academia with encouragement from her mother, Annette Lewis Phinazee, the first woman to earn a doctorate in library science from Columbia University.

Dr. Edelin went on to receive a PhD in philosophy, writing her dissertation on civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, and helped launch the Afro-American studies department at Northeastern University in Boston in 1973, serving as the program’s first chair. Under her leadership, the department soon changed its name to “African American studies,” embracing language that had circulated among scholars but was seldom used by the general public.

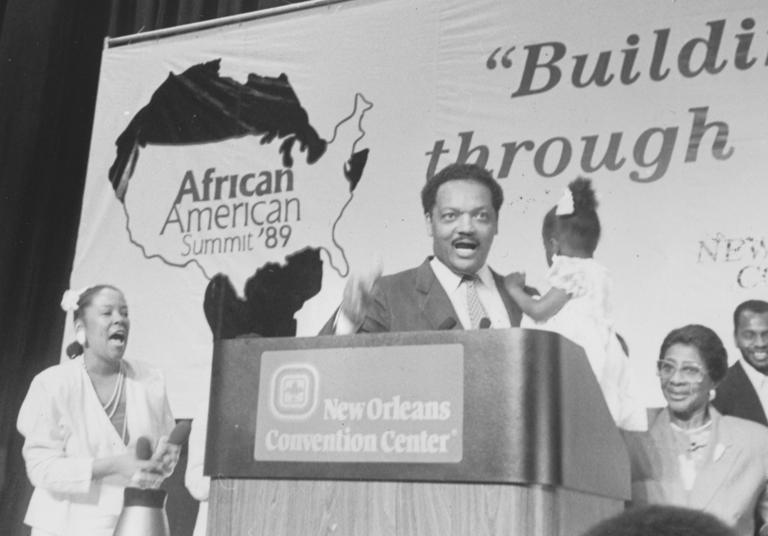

Dr. Edelin, left, with the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson at the 1989 African-American Summit in New Orleans.© Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

That began to change more than a decade later, when the term “African American” was adopted by 75 national Black leaders in the lead-up to a 1989 gathering called the African-American Summit. The meeting was convened by Jackson, the civil rights leader and former presidential candidate, who embraced the term “African American” and was widely credited with inspiring its widespread usage.

Investing OutlookElites Are Now Stockpiling Gold at the Fastest Pace in History

Ad

By all accounts, he and other Black leaders in the group decided to adopt the term at the suggestion of Dr. Edelin, who had traded scholarship for advocacy and was leading the National Urban Coalition, a Washington-based nonprofit. While helping organize the summit, Dr. Edelin argued that they should refer to themselves as African Americans instead of Blacks. The term offered historical context, she said, and linked Black Americans to the global African diaspora.

“The idea caught on,” she told the Boston Globe. “You could feel it.”

At a December 1988 news conference in Chicago, Jackson announced the preference for “African American,” speaking for summit organizers that included Dr. Edelin, NAACP leader Benjamin L. Hooks, civil rights activist C. Delores Tucker and former Gary, Ind., mayor Richard Hatcher. “Just as we were called Colored, but were not that, and then Negro, but not that, to be called Black is just as baseless,” he said, adding that “African American” “has cultural integrity” and “puts us in our proper historical context.”

Weeks later, the New York Times published a front-page story reporting that many African Americans agreed with Jackson. “The term has already shown up in the newest grade-school textbooks, been adopted by several black-run radio stations and newspapers around the country and appeared in the titles of popular books and in the conversations of many blacks as they warm to the idea and speak of visiting Africa one day,” wrote journalist Isabel Wilkerson.

There were still plenty of holdouts. Some critics found “African American” too wordy and worried that it was less powerful than “Black,” which evoked memories of the “Black is beautiful” campaign of the 1960s. Others dismissed the name-change debate as a distraction, saying that it was far less important than issues like unemployment, drug addiction and economic inequality.

For years, polls showed no strong consensus around the use of “Black” or “African American.” Both terms remain in widespread use.

As Dr. Edelin saw it, the question of terminology was about far more than a name. “Calling ourselves African Americans is the first step in the cultural offensive,” she told Ebony magazine, linking the name change to a “cultural renaissance” in which Black Americans reconnected with their history and heritage.

“Who are we if we don’t acknowledge our motherland?” she asked in a separate interview, adding that “when a child in a ghetto calls himself African American, immediately he’s international. You’ve taken him from the ghetto and put him on the globe.”

Dr. Edelin went on to receive a PhD in philosophy, writing her dissertation on civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, and helped launch the Afro-American studies department at Northeastern University in Boston in 1973, serving as the program’s first chair. Under her leadership, the department soon changed its name to “African American studies,” embracing language that had circulated among scholars but was seldom used by the general public.

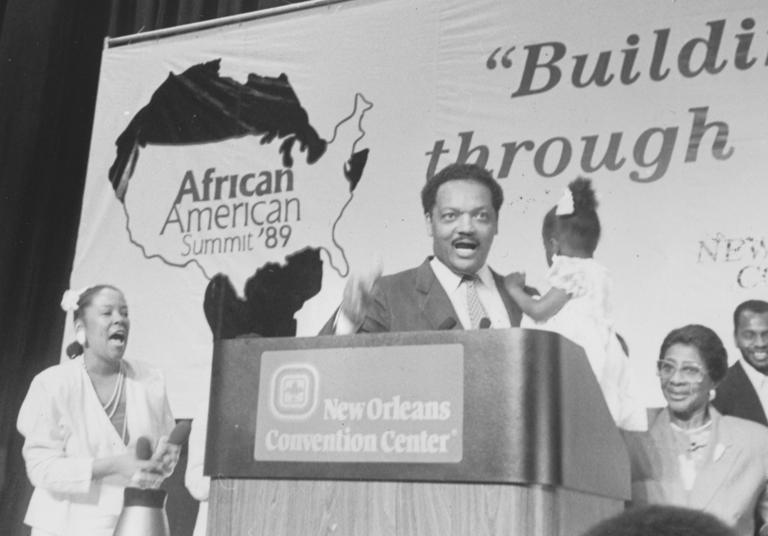

Dr. Edelin, left, with the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson at the 1989 African-American Summit in New Orleans.© Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

That began to change more than a decade later, when the term “African American” was adopted by 75 national Black leaders in the lead-up to a 1989 gathering called the African-American Summit. The meeting was convened by Jackson, the civil rights leader and former presidential candidate, who embraced the term “African American” and was widely credited with inspiring its widespread usage.

Investing OutlookElites Are Now Stockpiling Gold at the Fastest Pace in History

Ad

By all accounts, he and other Black leaders in the group decided to adopt the term at the suggestion of Dr. Edelin, who had traded scholarship for advocacy and was leading the National Urban Coalition, a Washington-based nonprofit. While helping organize the summit, Dr. Edelin argued that they should refer to themselves as African Americans instead of Blacks. The term offered historical context, she said, and linked Black Americans to the global African diaspora.

“The idea caught on,” she told the Boston Globe. “You could feel it.”

At a December 1988 news conference in Chicago, Jackson announced the preference for “African American,” speaking for summit organizers that included Dr. Edelin, NAACP leader Benjamin L. Hooks, civil rights activist C. Delores Tucker and former Gary, Ind., mayor Richard Hatcher. “Just as we were called Colored, but were not that, and then Negro, but not that, to be called Black is just as baseless,” he said, adding that “African American” “has cultural integrity” and “puts us in our proper historical context.”

Weeks later, the New York Times published a front-page story reporting that many African Americans agreed with Jackson. “The term has already shown up in the newest grade-school textbooks, been adopted by several black-run radio stations and newspapers around the country and appeared in the titles of popular books and in the conversations of many blacks as they warm to the idea and speak of visiting Africa one day,” wrote journalist Isabel Wilkerson.

There were still plenty of holdouts. Some critics found “African American” too wordy and worried that it was less powerful than “Black,” which evoked memories of the “Black is beautiful” campaign of the 1960s. Others dismissed the name-change debate as a distraction, saying that it was far less important than issues like unemployment, drug addiction and economic inequality.

For years, polls showed no strong consensus around the use of “Black” or “African American.” Both terms remain in widespread use.

As Dr. Edelin saw it, the question of terminology was about far more than a name. “Calling ourselves African Americans is the first step in the cultural offensive,” she told Ebony magazine, linking the name change to a “cultural renaissance” in which Black Americans reconnected with their history and heritage.

“Who are we if we don’t acknowledge our motherland?” she asked in a separate interview, adding that “when a child in a ghetto calls himself African American, immediately he’s international. You’ve taken him from the ghetto and put him on the globe.”