Diversity and Inclusion

Is racism in the UK really as bad in the US?

Bring up the Black Lives Matter movement or racism in the UK and you’ll likely see someone roll their eyes and say that the UK isn’t as racist as the US.

Even those who hold positions that usually require impartiality seem to express disbelief that anyone could liken the UK to the US in terms of racism. Watch below for the exchange between Newsnight journalist Emily Maitlis and award-winning podcaster George Mpanga, known by his stage name, George the Poet.

As Mpanga names the victims of Black British people who have died with involvement from the police, it’s clear that this isn’t exclusively an American problem. The scale is different, but the problem is still present and in need of addressing.

After the poor handling of the racist attack that killed Black 18-year-old Stephen Lawrence, the Macpherson report identified in 1999 that there was “institutional racism” in the Metropolitan police. Maitlis alludes to the report in the interview and gently implies that the existence of the report will have helped make headway on the issue of institutional racism.

Changes have been made since then. But racism isn’t just about police brutality.

Personal accounts and statistics suggest that even if things have improved, and even if police brutality isn’t “as bad” as the other side of the Atlantic, the UK still has plenty of work to do in addressing its racism.

Systemic racism in the UK is about more than police brutality

A 2020 YouGov survey shows that most people acknowledge that racism is still very real in the UK. But there has been a shift away from overt racism.

As the survey suggests, it’s “the type of racism [that we see in the UK] that has changed over time”.

[Racism is] not seen in England, but it’s felt. And it’s oppressive.

Daniel Kaluuya, actor

Here’s a snapshot view:

In England and Wales, Black people were nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people and eight times more likely to be tasered in 2019, even though white people are more likely to be found with illegal substances.

Black people are more likely to receive harsher treatment for mental health issues — for example, being compulsorily admitted and subject to seclusion or restraint.

According to the McGregor review, people of color are “more likely to be overqualified for the job that they are in”, but white people are more likely to be promoted.

In 2019, it was noted that there were fewer FTSE 100 ethnic minority CEOs than there were FTSE 100 CEOs called Steve.

While deaths in police custody are on a much smaller scale in the UK, the Angiolini Review found that Black people were more likely to die by police force than white people. The 2017 report highlighted the harmful stereotype that Black men are “dangerous, violent and volatile”.

The facts are clear: there is plenty of work to do in acknowledging and addressing what needs to be done about the UK’s racism.

As historian and broadcaster David Olusoga writes in The Guardian,

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history… For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognize American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties.

Everyday racism in the UK

So now we understand the facts, what do these “home-grown varieties” of racism actually look like?

We can’t tackle racism if we’re not able to spot and name the kind of racism we’re dealing with. Racism takes many forms. In the UK, racism often manifests in covert, everyday occurrences that sit out of plain sight, away from the public eye.

Not all acts of racism are overt or come from a place of hatred. Racism can happen through microaggressions — everyday speech or actions, like a look or gesture, that reinforces stereotypes or marginalizes groups. They’re usually said without harmful intention, but they have a harmful impact.

Microaggressions might sound like, “where are you really from?” — the implication being that someone doesn’t belong to their country because of how they look. Sometimes a microaggression is meant as a compliment, like saying “you’re one of the good ones”, the implication being that the person is an exception to a group that is inherently “bad”.

Likewise, racist stereotypes can lead us to make incorrect assumptions. For example, the reports of Black footballers who are stopped by police and asked if their car is stolen or Black barristers who are assumed to be the defendant. Stereotypes, including racist stereotypes like these, happen through socialization — through jokes, comments and one-sided portrayals of groups in film, TV and news reporting. It’s when we accept or act on them that we feed racism into whole systems and structures. This creates police forces who consistently treat Black people with suspicion and industries who reject job applicants with Asian or African heritage.

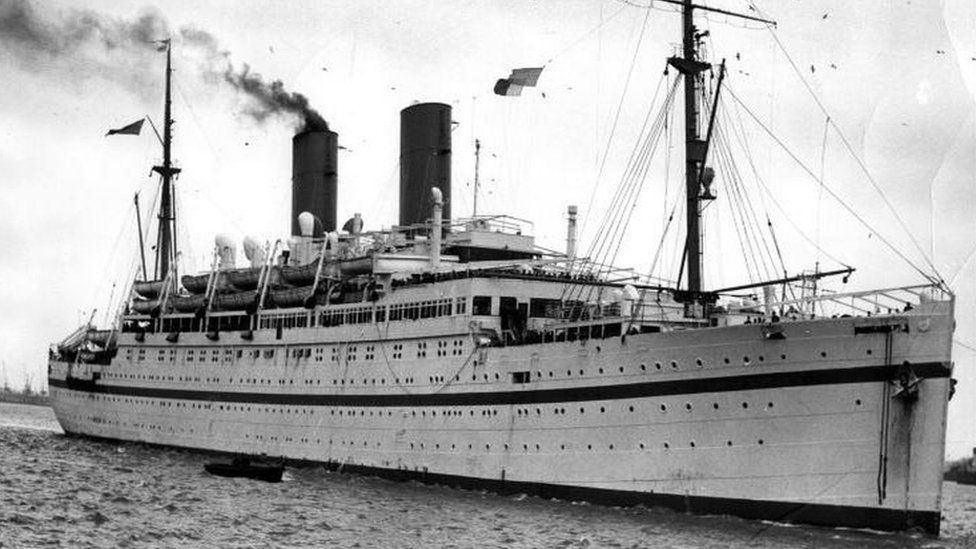

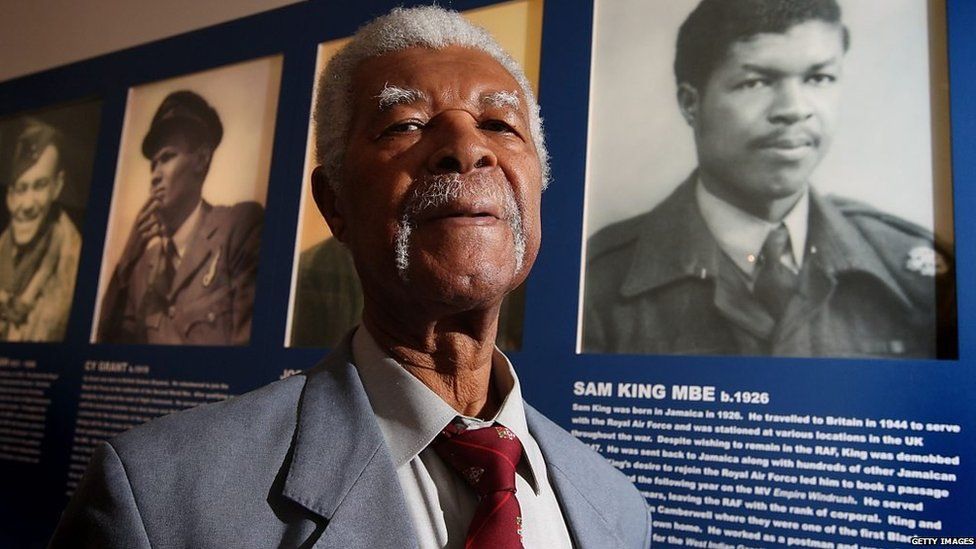

Racism can show up in decisions made by legislators and politicians that disregard the lives of Black people. A notable example of how one decision made by people with power can produce structural racism is the Windrush scandal. After decades of living and working legally in the UK, changes to immigration policy meant Black Britons were considered illegal and were in some cases wrongly deported.

Why we all need to be antiracist

Tackling racism is no small feat. To create lasting change, it’s up to every individual to take up the task of being actively antiracist. While there is still so much racism in force in the UK, we can’t keep deflecting to a worse situation while being passive within our own.

We need to choose to be actively antiracist. Passive antiracism doesn’t work, because doing nothing is the same as giving silent consent for the racism that thrives through systems.

It’s important to remember that we’re all human and we’re all still learning. Ibram X. Kendi, author of How To Be an Antiracist, talks about how a core part of antiracist work is holding ourselves accountable for racist thoughts and actions.

Being racist or antiracist isn’t something you say you are or aren’t, it’s something you do. And that means that we renew our potential to be either with every action we take.

Whatever point we’re each at in thinking and talking about race, we will all hugely benefit from learning more about racism and how to be antiracist.

Where to learn more about racism in the UK

Here’s how you can start taking antiracist action this week.

There are plenty of great antiracist reading lists just a Google search away, but here’s a starter for ten:

If you have the time, here are some longer reads:

For more resources that include a US lens, take a look at Penguin’s list of antiracism books.

As communications consultant Frankie Reddin wrote in Harper’s Bazaar and author Jasmine Guillory said in TIME Magazine, reading shouldn’t only stop at content that specifically focuses on antiracism — it needs to extend to fiction that explores Black stories with nuance, too.

Take a look at Booker Prize winner Bernadine Evaristo’s list of Black British female authors for Waterstones.

And it’s important that antiracist work goes beyond thinking and listening, too. Talking about racism at work is an important piece of the puzzle, and one that people find hard.

We’ve previously shared discussion guides and Workouts to help teams have open-minded and thoughtful conversations about racism and antiracism at work. Here are links to a few of them:

UK Black History Month Discussion Guides, complete guides to get teams talking about the Black British experience and racism in the UK by Hive Learning. Check out the discussion guides here.

Antiracism Workouts, interactive group sessions designed to get teams talking and sharing perspectives on antiracist topics by Hive Learning. Check out the antiracism Workouts here.

How to have smoother conversations about Black Lives Matter, a guide to addressing common objections when talking about Black Lives Matter by Hive Learning

Ultimately, pointing to America’s racism doesn’t change the fact that racism in the UK isn’t going away. Taking comfort in how much further there is to fall offers a false sense of security. It overshadows the need to improve on the reality of racism in the UK, and the reality is that it’s getting worse. The UK has seen an uptick in racial discrimination after the Brexit vote and police-recorded race hate crimes rose by 6% since 2018/19.

Addressing racism is never easy, whether it’s personal to you or because it adds an uncomfortable lens to the place you call home. We all have a part to play in combating racism as we encounter it in our everyday lives and channeling our energy into taking action in the spaces we’re able to influence.

Is racism in the UK really as bad in the US? - Hive Learning

.

Is racism in the UK really as bad in the US?

Bring up the Black Lives Matter movement or racism in the UK and you’ll likely see someone roll their eyes and say that the UK isn’t as racist as the US.

On the surface, it can seem like a fair point to make, particularly for people who have never really been personally affected by racism. After all, British headlines aren’t often filled with racially charged violence, and Britain’s relationship with slavery feels far removed from its shores in comparison to America’s, which is deeply embedded in the national consciousness. London is one of the most multicultural cities in the world. And if anything, household brands in the UK seem to be embracing the country’s diversity.Even those who hold positions that usually require impartiality seem to express disbelief that anyone could liken the UK to the US in terms of racism. Watch below for the exchange between Newsnight journalist Emily Maitlis and award-winning podcaster George Mpanga, known by his stage name, George the Poet.

Maitlis is right: British police don’t carry firearms. Police brutality in the US is a topic that comes up again and again because the effects are so devastating and yet it feels preventable.As Mpanga names the victims of Black British people who have died with involvement from the police, it’s clear that this isn’t exclusively an American problem. The scale is different, but the problem is still present and in need of addressing.

After the poor handling of the racist attack that killed Black 18-year-old Stephen Lawrence, the Macpherson report identified in 1999 that there was “institutional racism” in the Metropolitan police. Maitlis alludes to the report in the interview and gently implies that the existence of the report will have helped make headway on the issue of institutional racism.

Changes have been made since then. But racism isn’t just about police brutality.

Personal accounts and statistics suggest that even if things have improved, and even if police brutality isn’t “as bad” as the other side of the Atlantic, the UK still has plenty of work to do in addressing its racism.

Systemic racism in the UK is about more than police brutality

A 2020 YouGov survey shows that most people acknowledge that racism is still very real in the UK. But there has been a shift away from overt racism.

As the survey suggests, it’s “the type of racism [that we see in the UK] that has changed over time”.

[Racism is] not seen in England, but it’s felt. And it’s oppressive.

Daniel Kaluuya, actor

Here’s a snapshot view:

In England and Wales, Black people were nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people and eight times more likely to be tasered in 2019, even though white people are more likely to be found with illegal substances.

Black people are more likely to receive harsher treatment for mental health issues — for example, being compulsorily admitted and subject to seclusion or restraint.

According to the McGregor review, people of color are “more likely to be overqualified for the job that they are in”, but white people are more likely to be promoted.

In 2019, it was noted that there were fewer FTSE 100 ethnic minority CEOs than there were FTSE 100 CEOs called Steve.

While deaths in police custody are on a much smaller scale in the UK, the Angiolini Review found that Black people were more likely to die by police force than white people. The 2017 report highlighted the harmful stereotype that Black men are “dangerous, violent and volatile”.

The facts are clear: there is plenty of work to do in acknowledging and addressing what needs to be done about the UK’s racism.

As historian and broadcaster David Olusoga writes in The Guardian,

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history… For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognize American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties.

Everyday racism in the UK

So now we understand the facts, what do these “home-grown varieties” of racism actually look like?

We can’t tackle racism if we’re not able to spot and name the kind of racism we’re dealing with. Racism takes many forms. In the UK, racism often manifests in covert, everyday occurrences that sit out of plain sight, away from the public eye.

Not all acts of racism are overt or come from a place of hatred. Racism can happen through microaggressions — everyday speech or actions, like a look or gesture, that reinforces stereotypes or marginalizes groups. They’re usually said without harmful intention, but they have a harmful impact.

Microaggressions might sound like, “where are you really from?” — the implication being that someone doesn’t belong to their country because of how they look. Sometimes a microaggression is meant as a compliment, like saying “you’re one of the good ones”, the implication being that the person is an exception to a group that is inherently “bad”.

Likewise, racist stereotypes can lead us to make incorrect assumptions. For example, the reports of Black footballers who are stopped by police and asked if their car is stolen or Black barristers who are assumed to be the defendant. Stereotypes, including racist stereotypes like these, happen through socialization — through jokes, comments and one-sided portrayals of groups in film, TV and news reporting. It’s when we accept or act on them that we feed racism into whole systems and structures. This creates police forces who consistently treat Black people with suspicion and industries who reject job applicants with Asian or African heritage.

Racism can show up in decisions made by legislators and politicians that disregard the lives of Black people. A notable example of how one decision made by people with power can produce structural racism is the Windrush scandal. After decades of living and working legally in the UK, changes to immigration policy meant Black Britons were considered illegal and were in some cases wrongly deported.

Why we all need to be antiracist

Tackling racism is no small feat. To create lasting change, it’s up to every individual to take up the task of being actively antiracist. While there is still so much racism in force in the UK, we can’t keep deflecting to a worse situation while being passive within our own.

We need to choose to be actively antiracist. Passive antiracism doesn’t work, because doing nothing is the same as giving silent consent for the racism that thrives through systems.

It’s important to remember that we’re all human and we’re all still learning. Ibram X. Kendi, author of How To Be an Antiracist, talks about how a core part of antiracist work is holding ourselves accountable for racist thoughts and actions.

Being racist or antiracist isn’t something you say you are or aren’t, it’s something you do. And that means that we renew our potential to be either with every action we take.

Whatever point we’re each at in thinking and talking about race, we will all hugely benefit from learning more about racism and how to be antiracist.

Where to learn more about racism in the UK

Here’s how you can start taking antiracist action this week.

There are plenty of great antiracist reading lists just a Google search away, but here’s a starter for ten:

Young, British and Black, a collection of 50 stories by The Guardian

Akala x Black British History, a two-part video series, by author and rapper Akala

This Got Us Thinking: How do we confront the gaps in our Black history education?, a blog post with resources by Hive Learning

If you have the time, here are some longer reads:

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, award-winning non-fiction book by Reni Eddo-Lodge

Noughts and Crosses, YA fiction novel by Malorie Blackman

The Good Immigrant, essays edited by Nikesh Shukla

Black and British: A Forgotten History, non-fiction by David Olusoga

For more resources that include a US lens, take a look at Penguin’s list of antiracism books.

As communications consultant Frankie Reddin wrote in Harper’s Bazaar and author Jasmine Guillory said in TIME Magazine, reading shouldn’t only stop at content that specifically focuses on antiracism — it needs to extend to fiction that explores Black stories with nuance, too.

Take a look at Booker Prize winner Bernadine Evaristo’s list of Black British female authors for Waterstones.

And it’s important that antiracist work goes beyond thinking and listening, too. Talking about racism at work is an important piece of the puzzle, and one that people find hard.

We’ve previously shared discussion guides and Workouts to help teams have open-minded and thoughtful conversations about racism and antiracism at work. Here are links to a few of them:

UK Black History Month Discussion Guides, complete guides to get teams talking about the Black British experience and racism in the UK by Hive Learning. Check out the discussion guides here.

Antiracism Workouts, interactive group sessions designed to get teams talking and sharing perspectives on antiracist topics by Hive Learning. Check out the antiracism Workouts here.

How to have smoother conversations about Black Lives Matter, a guide to addressing common objections when talking about Black Lives Matter by Hive Learning

Ultimately, pointing to America’s racism doesn’t change the fact that racism in the UK isn’t going away. Taking comfort in how much further there is to fall offers a false sense of security. It overshadows the need to improve on the reality of racism in the UK, and the reality is that it’s getting worse. The UK has seen an uptick in racial discrimination after the Brexit vote and police-recorded race hate crimes rose by 6% since 2018/19.

Addressing racism is never easy, whether it’s personal to you or because it adds an uncomfortable lens to the place you call home. We all have a part to play in combating racism as we encounter it in our everyday lives and channeling our energy into taking action in the spaces we’re able to influence.

Is racism in the UK really as bad in the US? - Hive Learning

.