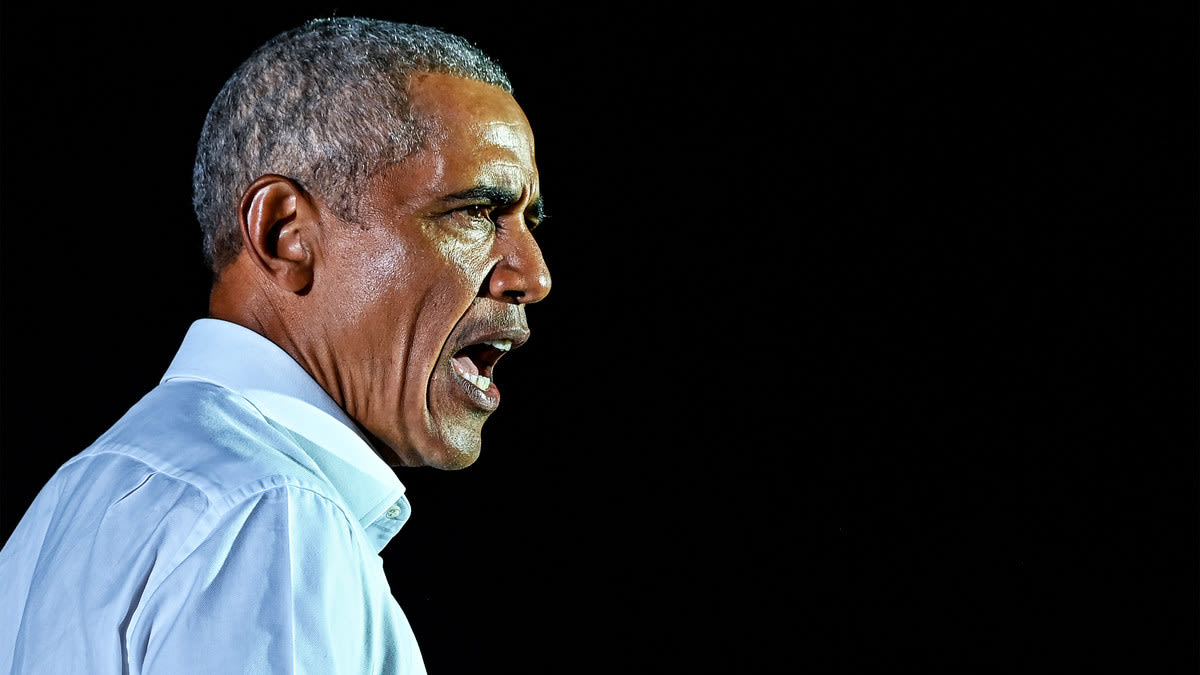

Obama’s New Book Is

Full of the Racial Honesty That He Avoided While he Was President

IN HINDSIGHT:

Even as he saw the rising tide of white racist hatred,

he exhibited a kind of racial denialism, emphasizing

that things had once been worse and

accommodating white resistance.

OPINION Getty

Kali Holloway

The Daily Beasthttps://www.thedailybeast.com/author/kali-holloway

Nov. 22, 2020

Recalling the arduous 2008 path that ultimately led to his first term in the White House, Barack Obama writes in his new presidential memoir, A Promised Land, that his campaign was careful to avoid leaning into any issues that might be construed as “racial grievance.” By this, of course, he means Black concerns about the lethal consequences of institutional white supremacist power.

“[T]oo much focus on civil rights, police misconduct or other issues considered specific to Black people risked triggering suspicion, if not a backlash from the broader electorate,” Obama writes. “You might decide to speak up anyway as a matter of conscience, but you understood there’d be a price.”

White feelings matter, in other words. More specifically, the white majority’s fears of Black equality, even as a mere political proposition, can sink Black electoral aspirations. This was implicitly understood by Black American voters, who forgave the candidate for avoiding full-throated advocacy for racial justice on the campaign trail, considering it a necessary calculation to quell the anti-Black imaginings of those “for whom the image of me in the White House involved a big psychological leap.” Like Obama, many believed “the immediate formula for racial progress” would be getting the first Black president into office, where change could happen.

But Obama’s public reticence on race—and more specifically, on anti-Black racism—would turn out not to be just a campaign strategy, but one of the defining characteristics of his years in office, and especially his first term. Yet even as he avoided the topic, white grievance festered, an expression of rage at a Black man occupying a seat of power that had been marked “whites only.” Long before his primary win, for the perceived affront of even joining the presidential race, “the number of threats directed my way exceeded anything the Secret Service had ever seen before” and the candidate was assigned a 24-hour security detail. The rise of the Tea Party, the obstructionism of Republicans who seized control of Congress in 2010, the birtherism of Donald Trump—all these signaled,

Those words were published in 2020, and there’s no way Obama could have predicted in 2009 that white resentment would run so deep as to send Trump into office on a wave of racism and xenophobia—that, as he writes, “millions of Americans spooked by a Black man in White House” would elect as his successor an incompetent lying conman who boasts about sexual assault to soothe “their racial anxiety.” But what is clear is that during the first three years of his presidency, Obama recognized the seething white racist reaction to his election and the ways that Republicans lawmakers stoked that anger to their own political ends.

This recognition is part of what prompted Obama to designate Joe Biden as his deal-maker with the Senate, since “in McConnell’s mind, negotiations with the Vice President didn’t inflame the Republican base in quite the same way that any appearance of cooperating with (Black, Muslim socialist) Obama was bound to do.” Obama saw, in then-House Majority Leader John Boehner’s false depiction of him as “angry” during budget talks, more evidence that the racism on full display during “the Tea Party summer had migrated from the fringe of the GOP to the center.” He writes of his frustration in warring with Republicans dedicated to “undoing whatever I’d done,” as the Grand Old Party “increasingly seemed to consider opposition to me to be its unifying principle, the objective that superseded” everything else. “Cooperate with the Obama administration at your own peril” became an unwritten rule among GOP lawmakers, he writes. “And if you have to shake his hand, make sure you don’t look happy doing it.”

What he did not do in response to any of this was respond in kind, rhetorically or otherwise. Writing about the Tea Party, whose blatantly racist protest signs, “enraged flag waving and inflammatory slogans” became a fixture on the nightly news, Obama notes that he “didn’t believe a president should ever publicly whine about criticism from voters,” which, fair point. But he also cites his team’s “reams of data telling us that white voters, including many who supported me, reacted poorly to lectures about race,” ultimately concluding, “I knew I wasn’t going to win over any voters by labeling my opponents racist.”

It seems obvious that the folks who most needed to be engaged in a discussion on race and personal responsibility weren’t recent Morehouse College graduates or Black congressional officials, but instead, those whose entitlement demanded unearned compensatory status based solely on their whiteness. And yet, the president’s soaring oratories, which acknowledged structural racism in the abstract, did not address the concreteness of anti-Black racism, the surge in toxic white racism under his presidency, the renewed creep of white racist terror. This, even as race-based hate crimes around the country increased immediately following his election, white racist group membership precipitously rose, and right-wing domestic terror grew to eclipse threats from abroad. Amidst all of that, the president proffered respectability politics to Black folks, despite the fact that the viciously racist response to his own ascent served as definitive proof that no measure of Black success made someone safe from white racism. Rather, Black success provokes bitter white reprisal.

It’s no wonder that a clearly perturbed Rep. Maxine Waters issued a justifiably defensive response to the president’s CBC speech, noting Obama did not condescend to other voting groups in the same way.

"I’m not sure who the president was addressing. I found that language a bit curious because the president spoke to the Hispanic Caucus, and certainly they're pushing him on immigration... he certainly didn't tell them to stop complaining. And he would never say that to the gay and lesbian community, who really pushed him on Don't Ask, Don't Tell,” Waters said. “So, I don't know who he was talking to because we're certainly not complaining. We're working. We support him, and we're protecting that base because we want people to be enthusiastic about him when that election rolls around."

But even as he strove toward that vision, he details in this new memoir that he was well aware of the rising tide of white racist hatred, despite publicly exhibiting a kind of racial denialism. It’s hard not to see this as accommodating white discomfort with the realities of racism, just as he had on the campaign trail.

It’s tempting to assume that Obama did not do these things because he assumed even the mildest expression of irritation was verboten, lest he be stereotyped as an “angry Black man.” Obama’s passing criticism of the white officer who arrested Black scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. as he attempted to enter his own home in 2009, which became the story at a press conference that was supposed to have been about passage of the Affordable Care Act, “caused a huge drop in my support among white voters, bigger than would come from any single event during the eight years of my presidency. It was support that I’d never completely get back.”

It remains disappointing that Obama did not speak more forcefully about the realities of race and anti-Black racism during his time in office. At the very least, his bootstrapping messaging to Black folks reinforced white myths about Black pathology, omitting historical truths that tell the full story of how this country has always, legislatively and extrajudicially, fought to maintain white supremacy and Black second-classness.

He writes in his memoir about how Black people have “grown skilled at suppressing our reactions to minor slights, ever ready to give white colleagues the benefit of the doubt, remaining mindful that all but the most careful discussions of race risked triggering in them a mild panic.” About how “the basis of our nation’s social order had never been simply about consent — that it was also about centuries of state sponsored violence by whites against Black and brown people, and that who controlled legally sanctioned violence, how it was wielded and against whom, still mattered in the recesses of our tribal minds more than we cared to admit.” He notes that white voters seemed to lack the empathy required to understand that “African Americans and other minority groups might need extra help from the government—that their specific hardships could be traced to a brutal history of discrimination rather than immutable characteristics or individual choices... Even universal programs that enjoyed broad support—like public education or public sector employment—had a funny way of becoming controversial once Black and brown people were added as beneficiaries.”

Where was this clarity and honesty when he was in office?

I don’t know if speaking this way would have mattered much to white folks broadly. It certainly would not have assuaged the racism of future white Trump voters and Rush Limbaugh listeners; there is nothing Obama could have said to those folks that would not have incurred their white racist wrath. And congressional Republicans would undoubtedly have shot down even the most tepid legislative proposals leading toward Black equality.

But I do know how much it would have meant for Black folks to be truly seen by a president who acknowledged and spoke to their American story. I am well aware that the American presidency is not meant to be a vehicle for real change, or an office that truly challenges the racial status quo. If Obama had only been more of a truth-teller during his tenure, to quote scholar Danielle Fuentes Morgan, “like Trump, he might have broken American politics, but in this case for good.”

Obama writes that his “first hundred days in office revealed a basic strand of my political character. I was a reformer, conservative in temperament if not vision,” and that he wasn’t up to prosecute people who’d done great damage to the country’s social fabric because that would have “required a violence to the social order,” even as he acknowledges that “omeone with a more revolutionary soul might respond that all this would have been worth it.”

Maybe, because the topic is the sudden financial crisis he’d inherited, Obama is more direct here about the limits of his nature and ambitions while grappling with American racism as president.

Obama’s New Book Is Full of the Racial Honesty That He Avoided While he Was President (thedailybeast.com)

www.thedailybeast.com

www.thedailybeast.com

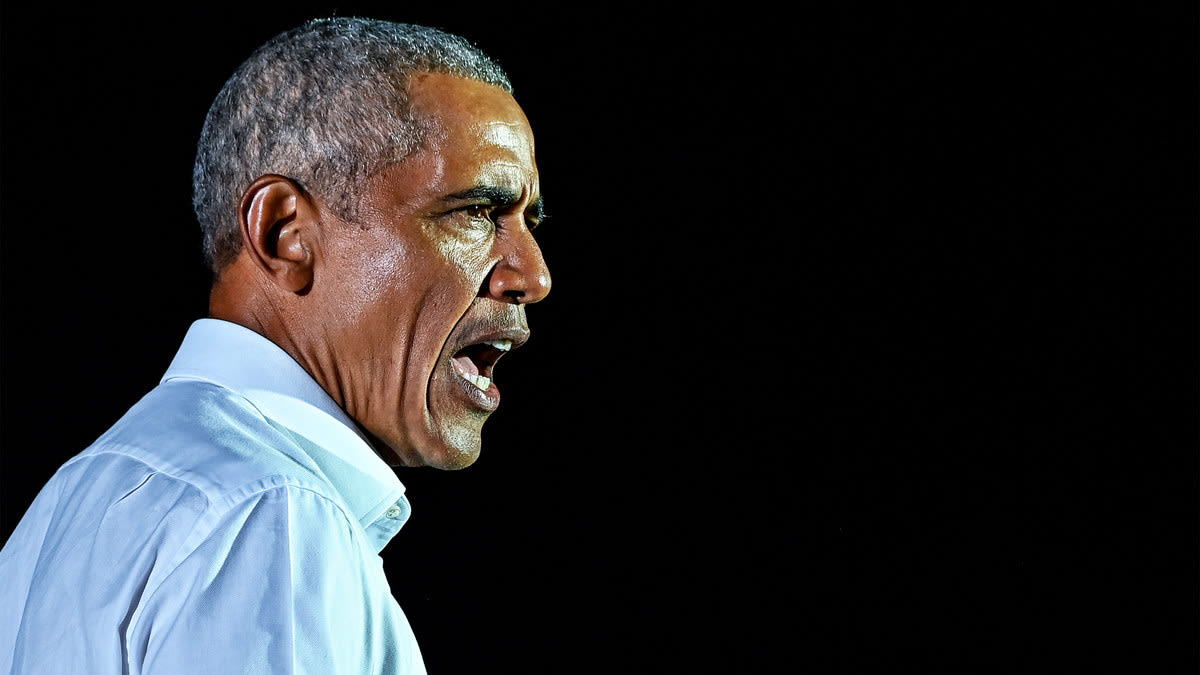

Full of the Racial Honesty That He Avoided While he Was President

IN HINDSIGHT:

Even as he saw the rising tide of white racist hatred,

he exhibited a kind of racial denialism, emphasizing

that things had once been worse and

accommodating white resistance.

OPINION Getty

Kali Holloway

The Daily Beasthttps://www.thedailybeast.com/author/kali-holloway

Nov. 22, 2020

Recalling the arduous 2008 path that ultimately led to his first term in the White House, Barack Obama writes in his new presidential memoir, A Promised Land, that his campaign was careful to avoid leaning into any issues that might be construed as “racial grievance.” By this, of course, he means Black concerns about the lethal consequences of institutional white supremacist power.

“[T]oo much focus on civil rights, police misconduct or other issues considered specific to Black people risked triggering suspicion, if not a backlash from the broader electorate,” Obama writes. “You might decide to speak up anyway as a matter of conscience, but you understood there’d be a price.”

White feelings matter, in other words. More specifically, the white majority’s fears of Black equality, even as a mere political proposition, can sink Black electoral aspirations. This was implicitly understood by Black American voters, who forgave the candidate for avoiding full-throated advocacy for racial justice on the campaign trail, considering it a necessary calculation to quell the anti-Black imaginings of those “for whom the image of me in the White House involved a big psychological leap.” Like Obama, many believed “the immediate formula for racial progress” would be getting the first Black president into office, where change could happen.

But Obama’s public reticence on race—and more specifically, on anti-Black racism—would turn out not to be just a campaign strategy, but one of the defining characteristics of his years in office, and especially his first term. Yet even as he avoided the topic, white grievance festered, an expression of rage at a Black man occupying a seat of power that had been marked “whites only.” Long before his primary win, for the perceived affront of even joining the presidential race, “the number of threats directed my way exceeded anything the Secret Service had ever seen before” and the candidate was assigned a 24-hour security detail. The rise of the Tea Party, the obstructionism of Republicans who seized control of Congress in 2010, the birtherism of Donald Trump—all these signaled,

“an emotional, almost visceral reaction to my presidency, distinct

from any differences in policy or ideology. It was as if my very

presence in the White House had triggered a deep-seated

panic, a sense that the natural order had been disrupted.”

Those words were published in 2020, and there’s no way Obama could have predicted in 2009 that white resentment would run so deep as to send Trump into office on a wave of racism and xenophobia—that, as he writes, “millions of Americans spooked by a Black man in White House” would elect as his successor an incompetent lying conman who boasts about sexual assault to soothe “their racial anxiety.” But what is clear is that during the first three years of his presidency, Obama recognized the seething white racist reaction to his election and the ways that Republicans lawmakers stoked that anger to their own political ends.

This recognition is part of what prompted Obama to designate Joe Biden as his deal-maker with the Senate, since “in McConnell’s mind, negotiations with the Vice President didn’t inflame the Republican base in quite the same way that any appearance of cooperating with (Black, Muslim socialist) Obama was bound to do.” Obama saw, in then-House Majority Leader John Boehner’s false depiction of him as “angry” during budget talks, more evidence that the racism on full display during “the Tea Party summer had migrated from the fringe of the GOP to the center.” He writes of his frustration in warring with Republicans dedicated to “undoing whatever I’d done,” as the Grand Old Party “increasingly seemed to consider opposition to me to be its unifying principle, the objective that superseded” everything else. “Cooperate with the Obama administration at your own peril” became an unwritten rule among GOP lawmakers, he writes. “And if you have to shake his hand, make sure you don’t look happy doing it.”

What he did not do in response to any of this was respond in kind, rhetorically or otherwise. Writing about the Tea Party, whose blatantly racist protest signs, “enraged flag waving and inflammatory slogans” became a fixture on the nightly news, Obama notes that he “didn’t believe a president should ever publicly whine about criticism from voters,” which, fair point. But he also cites his team’s “reams of data telling us that white voters, including many who supported me, reacted poorly to lectures about race,” ultimately concluding, “I knew I wasn’t going to win over any voters by labeling my opponents racist.”

“The president proffered respectability politics to Black folks,

despite the fact that the viciously racist response to his own

ascent served as definitive proof that no measure

of Black success made someone safe from white racism.”

Those “lectures about race” that Obama refrained from giving white audiences were instead delivered to Black folks. In his 2013 commencement speech at Morehouse, the then-president patronizingly informed a class of new graduates that “whatever hardships you may experience because of your race, they pale in comparison to the hardships previous generations endured and overcame,” along with the admonition that “there's no longer any room for excuses.” At the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington the same year, Obama claimed that “if we're honest with ourselves, we'll admit that… there were times when some of us claiming to push for change lost our way. The anguish of assassinations set off self-defeating riots. Legitimate grievances against police brutality tipped into excuse-making for criminal behavior.” Speaking to the assembled Congressional Black Caucus in 2011, he told members to “take off your bedroom slippers, put on your marching shoes. Shake it off. Stop complaining, stop grumbling, stop crying.”It seems obvious that the folks who most needed to be engaged in a discussion on race and personal responsibility weren’t recent Morehouse College graduates or Black congressional officials, but instead, those whose entitlement demanded unearned compensatory status based solely on their whiteness. And yet, the president’s soaring oratories, which acknowledged structural racism in the abstract, did not address the concreteness of anti-Black racism, the surge in toxic white racism under his presidency, the renewed creep of white racist terror. This, even as race-based hate crimes around the country increased immediately following his election, white racist group membership precipitously rose, and right-wing domestic terror grew to eclipse threats from abroad. Amidst all of that, the president proffered respectability politics to Black folks, despite the fact that the viciously racist response to his own ascent served as definitive proof that no measure of Black success made someone safe from white racism. Rather, Black success provokes bitter white reprisal.

It’s no wonder that a clearly perturbed Rep. Maxine Waters issued a justifiably defensive response to the president’s CBC speech, noting Obama did not condescend to other voting groups in the same way.

"I’m not sure who the president was addressing. I found that language a bit curious because the president spoke to the Hispanic Caucus, and certainly they're pushing him on immigration... he certainly didn't tell them to stop complaining. And he would never say that to the gay and lesbian community, who really pushed him on Don't Ask, Don't Tell,” Waters said. “So, I don't know who he was talking to because we're certainly not complaining. We're working. We support him, and we're protecting that base because we want people to be enthusiastic about him when that election rolls around."

“Publicly, Obama exhibited a kind of racial denialism,

consistently emphasizing that things had once been worse.”

Obama’s reluctance to discuss racism is often attributed to the same intense, almost blinding optimism that led him to believe he could, against all historical odds, clinch the presidency in the first place. It was there in the most cited lines from the 2004 Democratic National Convention speech that made him a political star: “There is not a Black America and a white America and a Latino America and Asian America. There is the United States of America.” In his memoir, he says that the sentiment “was more a statement of aspiration than a description of reality, but it was an aspiration I believed in and a reality I strove for.”But even as he strove toward that vision, he details in this new memoir that he was well aware of the rising tide of white racist hatred, despite publicly exhibiting a kind of racial denialism. It’s hard not to see this as accommodating white discomfort with the realities of racism, just as he had on the campaign trail.

It’s tempting to assume that Obama did not do these things because he assumed even the mildest expression of irritation was verboten, lest he be stereotyped as an “angry Black man.” Obama’s passing criticism of the white officer who arrested Black scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. as he attempted to enter his own home in 2009, which became the story at a press conference that was supposed to have been about passage of the Affordable Care Act, “caused a huge drop in my support among white voters, bigger than would come from any single event during the eight years of my presidency. It was support that I’d never completely get back.”

It remains disappointing that Obama did not speak more forcefully about the realities of race and anti-Black racism during his time in office. At the very least, his bootstrapping messaging to Black folks reinforced white myths about Black pathology, omitting historical truths that tell the full story of how this country has always, legislatively and extrajudicially, fought to maintain white supremacy and Black second-classness.

He writes in his memoir about how Black people have “grown skilled at suppressing our reactions to minor slights, ever ready to give white colleagues the benefit of the doubt, remaining mindful that all but the most careful discussions of race risked triggering in them a mild panic.” About how “the basis of our nation’s social order had never been simply about consent — that it was also about centuries of state sponsored violence by whites against Black and brown people, and that who controlled legally sanctioned violence, how it was wielded and against whom, still mattered in the recesses of our tribal minds more than we cared to admit.” He notes that white voters seemed to lack the empathy required to understand that “African Americans and other minority groups might need extra help from the government—that their specific hardships could be traced to a brutal history of discrimination rather than immutable characteristics or individual choices... Even universal programs that enjoyed broad support—like public education or public sector employment—had a funny way of becoming controversial once Black and brown people were added as beneficiaries.”

Where was this clarity and honesty when he was in office?

I don’t know if speaking this way would have mattered much to white folks broadly. It certainly would not have assuaged the racism of future white Trump voters and Rush Limbaugh listeners; there is nothing Obama could have said to those folks that would not have incurred their white racist wrath. And congressional Republicans would undoubtedly have shot down even the most tepid legislative proposals leading toward Black equality.

But I do know how much it would have meant for Black folks to be truly seen by a president who acknowledged and spoke to their American story. I am well aware that the American presidency is not meant to be a vehicle for real change, or an office that truly challenges the racial status quo. If Obama had only been more of a truth-teller during his tenure, to quote scholar Danielle Fuentes Morgan, “like Trump, he might have broken American politics, but in this case for good.”

Obama writes that his “first hundred days in office revealed a basic strand of my political character. I was a reformer, conservative in temperament if not vision,” and that he wasn’t up to prosecute people who’d done great damage to the country’s social fabric because that would have “required a violence to the social order,” even as he acknowledges that “omeone with a more revolutionary soul might respond that all this would have been worth it.”

Maybe, because the topic is the sudden financial crisis he’d inherited, Obama is more direct here about the limits of his nature and ambitions while grappling with American racism as president.

Obama’s New Book Is Full of the Racial Honesty That He Avoided While he Was President (thedailybeast.com)

Obama’s New Book Is Full of the Racial Honesty That He Avoided While he Was President

Even as he saw the rising tide of white racist hatred, he exhibited a kind of racial denialism, emphasizing that things had once been worse and accommodating white resistance.