Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement

SUMMARY: The government’s response to

known connections of law enforcement

officers to violent racist and militant groups

has been strikingly insufficient.

The Brannan Center for Justice

By Michael German

August 27, 2020

Introduction

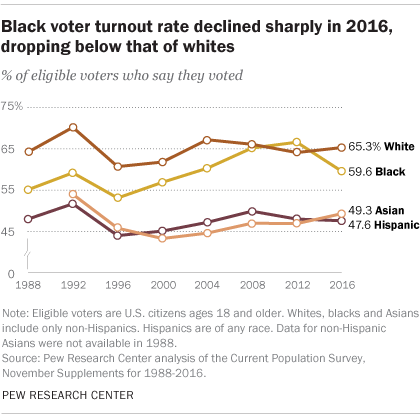

Racial disparities have long pervaded every step of the criminal justice process, from police stops, searches, arrests, shootings and other uses of force to charging decisions, wrongful convictions, and sentences. footnote1_82nauxd1 As a result, many have concluded that a structural or institutional bias against people of color, shaped by long-standing racial, economic, and social inequities, infects the criminal justice system. footnote2_km2l20m2 These systemic inequities can also instill implicit biases — unconscious prejudices that favor in-groups and stigmatize out-groups — among individual law enforcement officials, influencing their day-to-day actions while interacting with the public.

Police reforms, often imposed after incidents of racist misconduct or brutality, have focused on addressing these unconscious manifestations of bias. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), for example, has required implicit bias training as part of consent decrees it imposes to root out discriminatory practices in law enforcement agencies. Such training measures are designed to help law enforcement officers recognize these unconscious biases in order to reduce their influence on police behavior.

These reforms, while well-intentioned, leave unaddressed an especially harmful form of bias, which remains entrenched within law enforcement: explicit racism. Explicit racism in law enforcement takes many forms, from membership or affiliation with violent white supremacist or far-right militant groups, to engaging in racially discriminatory behavior toward the public or law enforcement colleagues, to making racist remarks and sharing them on social media. While it is widely acknowledged that racist officers subsist within police departments around the country, federal, state, and local governments are doing far too little to proactively identify them, report their behavior to prosecutors who might unwittingly rely on their testimony in criminal cases, or protect the diverse communities they are sworn to serve.

Efforts to address systemic and implicit biases in law enforcement are unlikely to be effective in reducing the racial disparities in the criminal justice system as long as explicit racism in law enforcement continues to endure. There is ample evidence to demonstrate that it does.

In 2017, the FBI reported that white supremacists posed a “persistent threat of lethal violence” that has produced more fatalities than any other category of domestic terrorists since 2000. footnote3_hulpaeu3 Alarmingly, internal FBI policy documents have also warned agents assigned to domestic terrorism cases that the white supremacist and anti-government militia groups they investigate often have “active links” to law enforcement officials. footnote4_bu78ixe4

The harms that armed law enforcement officers affiliated with violent white supremacist and anti-government militia groups can inflict on American society could hardly be overstated. Yet despite the FBI’s acknowledgement of the links between law enforcement and these suspected terrorist groups, the Justice Department has no national strategy designed to identify white supremacist police officers or to protect the safety and civil rights of the communities they patrol.

Obviously, only a tiny percentage of law enforcement officials are likely to be active members of white supremacist groups. But one doesn’t need access to secretive intelligence gathered in FBI terrorism investigations to find evidence of overt and explicit racism within law enforcement. Since 2000, law enforcement officials with alleged connections to white supremacist groups or far-right militant activities have been exposed in Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and elsewhere. footnote5_eompaaw5 Research organizations have uncovered hundreds of federal, state, and local law enforcement officials participating in racist, nativist, and sexist social media activity, which demonstrates that overt bias is far too common. footnote6_cj2sx6q6 These officers’ racist activities are often known within their departments, but only result in disciplinary action or termination if they trigger public scandals.

Few law enforcement agencies have policies that specifically prohibit affiliating with white supremacist groups. Instead, these officers typically face discipline, if at all, for more generally defined prohibitions against conduct detrimental to the department or for violations of anti-discrimination regulations or social media policies. Firings often lead to prolonged litigation, with dismissed officers claiming violations of their First Amendment speech and association rights. Most courts have upheld dismissals of police officers who have affiliated with racist or militant groups, following Supreme Court decisions limiting free speech rights for public employees to matters of public concern. footnote7_fcjnjsz7 Courts have given law enforcement agencies even greater latitude to restrict speech and association, citing their “heightened need for order, loyalty, morale and harmony.” footnote8_1maz1dp8

Some officers who have associated with militant groups or engaged in racist behavior have not been fired, however, or have had their dismissals overturned by courts or in arbitration. Such due process is required to ensure integrity and equity in the disciplinary process and protect falsely accused police officers from unjust punishments. Certainly, there will be cases where an officer’s behavior can be corrected with remedial measures short of termination. But leaving officers tainted by racist behavior in a job with immense discretion to take a person’s life and liberty requires a detailed supervision plan to mitigate the potential threats they pose to the communities they police, implemented with sufficient transparency to restore public trust.

Progress in removing explicit racism from law enforcement has clearly been made since the civil rights era, when Ku Klux Klan–affiliated officers were far too common. But, as Georgetown University law professor Vida B. Johnson argues, “The system can never achieve its purported goal of fairness while white supremacists continue to hide within police departments.” footnote9_6eunqy39 Trust in the police remains low among people of color, who are often victims of police violence and abuse and are disproportionately underserved as victims of crime. footnote10_9ru5zm610 The failure of law enforcement to adequately respond to racist violence and hate crimes or properly police white supremacist riots in cities across the United States over the last several years has left many Americans concerned that bias in law enforcement is pervasive. footnote11_i2on4c911 This report examines the law enforcement response to racist behavior, white supremacy, and far-right militancy within the ranks and recommends policy solutions to inform a more effective response.

Inadequate Response to Affiliations with White Supremacist and Militant Groups

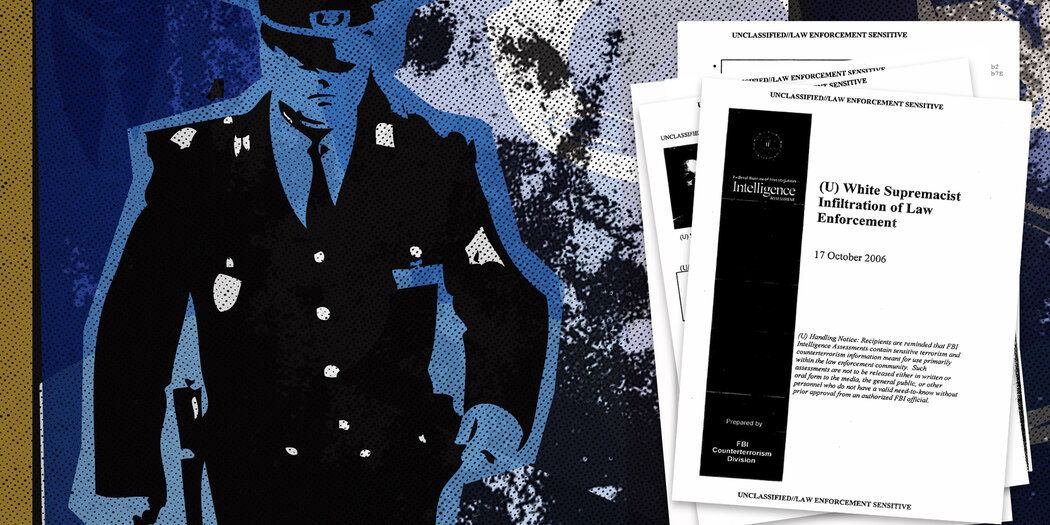

The FBI’s 2015 Counterterrorism Policy Directive and Policy Guide warns that “domestic terrorism investigations focused on militia extremists, white supremacist extremists, and sovereign citizen extremists often have identified active links to law enforcement officers.” footnote1_szgn3os12 This alarming declaration followed a 2006 intelligence assessment, based on FBI investigations and open sources, that warned of “white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement . . . by organized groups and by self-initiated infiltration by law enforcement personnel sympathetic to white supremacist causes.” footnote2_7z8mpgh13 Active links between law enforcement officials and the subjects of any terrorism investigation should raise alarms within our national security establishment, but the federal government has not responded accordingly.

The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have identified white supremacists as the most lethal domestic terrorist threat to the United States. footnote3_pbq2b0m14 In recent years, white supremacists have executed deadly rampages in Charleston, South Carolina, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and El Paso, Texas. footnote4_kl6umul15 Narrowly thwarted attempts by neo-Nazis to manufacture radiological “dirty” bombs in Maine in 2009 and Florida in 2017 show their dangerous capability and intent to unleash mass destruction. footnote5_suyrmw116 These groups also pose a lethal threat to law enforcement, as evidenced by recent attacks against Federal Protective Service officers and sheriff’s deputies in California by far-right militants intent on starting the “Boogaloo” — a euphemism for a new civil war — which killed two and injured several others. footnote6_r0sowcx17

Any law enforcement officers associating with these groups should be treated as a matter of urgent concern. Operating under color of law, such officers put the lives and liberty of people of color, religious minorities, LGBTQ+ people, and anti-racist activists at extreme risk, both through the violence they can mete out directly and by their failure to properly respond when these communities are victimized by other racist violent crime. Biased policing also tears at the fabric of American society by undermining public trust in equal justice and the rule of law.

The FBI’s 2006 assessment, however, takes a narrower view. It claims that “the primary threat” posed by the infiltration or recruitment of police officers into white supremacist or other far-right militant groups “arises from the areas of intelligence collection and exploitation, which can lead to investigative breaches and can jeopardize the safety of law enforcement sources or personnel.” footnote7_4n1fidz18 Though the FBI redacted significant passages of the assessment before releasing it to the public, the document does not appear to address any of the potential harms these bigoted officers pose to communities of color they police or to society at large. Rather, it identifies the main problem as a risk to the integrity of FBI investigations and the security of its agents and informants.

In a June 2019 hearing before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, Rep. William Lacy Clay (D-MO) asked Michael McGarrity, the FBI’s assistant director for counterterrorism, whether the bureau remained concerned about white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement since the publication of the 2006 assessment. McGarrity indicated he had not read the 2006 assessment. footnote8_zguc8l119

When asked more generally about the issue, McGarrity said he would be “suspect” of white supremacist police officers, but that their ideology was a First Amendment–protected right. The 2006 assessment addresses this concern, however, correctly summarizing Supreme Court precedent on the issue: “Although the First Amendment’s freedom of association provision protects an individual’s right to join white supremacist groups for the purposes of lawful activity, the government can limit the employment opportunities of group members who hold sensitive public sector jobs, including jobs within law enforcement, when their memberships would interfere with their duties.” footnote9_0hynwu620

More importantly, the FBI’s 2015 counterterrorism policy, which McGarrity was responsible for implementing, indicates not just that members of law enforcement might hold white supremacist views, but that FBI domestic terrorism investigations have often identified “active links” between the subjects of these investigations and law enforcement officials. Its proposed remedy is stunningly inadequate, however. The guide simply instructs agents to use the “silent hit” feature of the Terrorist Screening Center watchlist so that police officers searching for themselves or their white supremacist associates could not ascertain whether they were under FBI scrutiny.

While it is important to protect the integrity of FBI terrorism investigations and the safety of law enforcement personnel, Congress has also tasked the FBI with protecting the civil rights of American communities often targeted with discriminatory stops, searches, arrests, and brutality at the hands of police officers. The issue in these cases isn’t ideology but law enforcement connections to subjects of active terrorism investigations. It is unlikely that the FBI would be similarly hesitant to act if it received information that U.S. law enforcement officials were actively linked to terrorist groups like al-Qaeda or ISIS, or to criminal organizations like street gangs or the Mafia. Yet many of the white supremacist groups investigated by the FBI have longer and more violent histories than these other organizations. The federal response to known connections of law enforcement officers to white supremacist and far-right militant groups has been strikingly insufficient.

A Long History of Law Enforcement Involvement in White Supremacist Violence

White supremacy was central to the founding of the United States, sanctified in law and practice. It was the driving ideology behind the European colonization of North America, the subjugation of Native Americans, and the enslavement of kidnapped Africans and their descendants. Policing in the early American colonies was often less about crime control than maintaining the racial social order, ensuring a stable labor force, and protecting the property interests of the white privileged class. Slave patrols were among the first public policing organizations formed in the American colonies. footnote1_wx7ughf21 Put simply, white supremacy was the law these earliest public officials were sworn to enforce. Even states such as New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois that banned slavery enacted racist “Black laws,” which restricted travel and denied civil rights regarding voting, education, employment, and even residency for free Black people. footnote2_ljelgug22 The U.S. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required law enforcement officials in free states to return escaped slaves to their enslavers in the South. footnote3_ue50urr23

When slavery was finally abolished in the United States after the Civil War, de jure white supremacy lived on through Black codes and Jim Crow laws. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, an openly racist law halting Chinese immigration and denying naturalization to Chinese nationals already living in the United States. footnote4_kfibbk724 The Immigration Act of 1924 was also explicitly racist, codifying strict national origin quotas to limit Italian, eastern European, and nonwhite immigration. The law barred all immigration from Japan and other Asian countries not already excluded by previous legislation. footnote5_1uktj9z25

As the United States expanded westward, government agents enforced policies of violent ethnic cleansing against Native Americans and Mexican Americans. In the early 20th century, Texas Rangers led lynching parties that targeted Mexican Americans residing in Texas border towns on specious allegations of banditry. footnote6_6dw98sy26 Where the laws were deemed insufficient to dissuade nonwhites and non-Protestants from exercising their civil rights, reactionary groups such as the Ku Klux Klan used terrorist violence to enforce white supremacy. Law enforcement officials often participated in this violence directly or supported it by refusing to fulfill their duty to protect the peace and hold lawbreakers to account. By the 1920s, the KKK alone claimed 1 million members nationwide from New England to California, and had fully infiltrated federal, state, and local governments to advance its exclusionist agenda. footnote7_5y6jfun27

Many states outside the Deep South maintained “sundown towns” where police officers and vigilante mobs enforced official and quasi-official policies prohibiting Black (and often other nonwhite) people from remaining in town past sunset. footnote8_byje26c28 Into the 1970s, there were an estimated 10,000 sundown towns across the United States. footnote9_w8ck9l429 Police enforcement of white supremacy was never just a regional problem.

Hidden in Plain Sight

In 1964, civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner went missing in Mississippi during the Freedom Summer voter registration drive, shortly after being released from a Philadelphia, Mississippi, jail where they had been taken to pay a speeding fine. footnote1_56r5dfe30 President Lyndon Johnson ordered FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to send FBI agents to find them. Searchers found the bodies of eight black men, including two college students who were working on the voter registration drive, before an informant’s tip finally led the agents to an earthen dam where Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were buried. After local law enforcement refused to investigate the murders, the Justice Department charged 19 Ku Klux Klansmen with conspiring to violate Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner’s civil rights. Two current and two former law enforcement officials were among those charged. An all-white jury convicted seven of the Klansman but only one of the law enforcement officers. footnote2_slqiz5w31

While the Mississippi Burning case was the most notorious, it was far from the last time white supremacist law enforcement officers engaged in racist violence. There is an unbroken chain of law enforcement involvement in violent, organized racist activity right up to the present. In the 1980s, the investigation of a KKK firebombing of a Black family’s home in Kentucky exposed a Jefferson County police officer as a Klan leader. In a deposition, the officer admitted that he directed a 40-member Klan subgroup called the Confederate Officers Patriot Squad (COPS), half of whom were police officers. He added that his involvement in the KKK was known to his police department and tolerated so long as he didn’t publicize it. footnote3_9amzido32

In the 1990s, Lynwood, California, residents filed a class action civil rights lawsuit alleging that a gang of racist Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies known as the Lynwood Vikings perpetrated “systematic acts of shooting, killing, brutality, terrorism, house-trashing and other acts of lawlessness and wanton abuse of power.” footnote4_plfc5fb33 A federal judge overseeing the case labeled the Vikings “a neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” within the sheriff’s department that engaged in racially motivated violence and intimidation against the Black and Latino communities. In 1996, the county paid $9 million in settlements. footnote5_e3konme34

Recent reporting suggests this overtly racist gang activity within the sheriff’s department continues. footnote6_fjnq9bf35 In 2019, Los Angeles County paid $7 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit against two sheriff’s deputies for shooting an unarmed Black man after testimony revealed that they were part of a group of deputies with matching tattoos in the tradition of earlier deputy gangs. A pending lawsuit accuses the same two officers of beating an unarmed Black man while yelling racial epithets. footnote7_46dl4l836 A Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors investigation revealed that almost 60 lawsuits against alleged members of deputy gangs have cost the county about $55 million, which includes $21 million in cases over the last 10 years. These deputy gangs pose a threat to their fellow law enforcement officers as well, according to two recently filed lawsuits. In one, a deputy alleges he had been bullied by deputy gang members for five years, and finally viciously beaten by the gang’s enforcer. footnote8_3nzwfg837 In another, a deputy who witnessed the attack alleged he suffered threats and retaliation from deputy gang members after reporting it to an internal affairs tip line. footnote9_tqejc0l38 In 2019, the FBI reportedly initiated a civil rights investigation regarding gang activity at the sheriff’s department. footnote10_ce705tl39

Only rarely do these cases lead to criminal charges. In 2017, Florida state prosecutors convicted three prison guards of plotting with fellow KKK members to murder an inmate. footnote11_zmr81zz40 Federal prosecutions are even rarer. In 2019, the Justice Department charged a New Jersey police chief with a hate crime for assaulting a Black teenager during a trespassing arrest after several of his deputies recorded his numerous racist rants. This incident marked the first time in more than a decade that federal prosecutors charged a law enforcement official for an on-duty use of force as a hate crime. footnote12_fzatpjz41 A jury convicted the police chief of lying to FBI agents but was unable to reach a verdict on the hate crime charge, which prosecutors vowed to retry. footnote13_ealooqm42

More often, police officers with ties to white supremacist groups or overt racist behavior are subjected to internal disciplinary procedures rather than prosecution. In 2001, two Texas sheriff’s deputies were fired after they exposed their KKK affiliation in an attempt to recruit other officers. footnote14_msxm58q43 In 2005, an internal investigation revealed a Nebraska state trooper was participating in a members-only KKK chat room. footnote15_mx8o3wy44 He was fired in 2006 but won his job back in an arbitration mandated by the state’s collective bargaining agreement. On appeal, the Nebraska Supreme Court upheld his dismissal, determining that the arbitration decision violated “the explicit, well-defined, and dominant public policy that laws should be enforced without racial or religious discrimination, and the public should reasonably perceive this to be so.” footnote16_a5e6nau45 Three police officers in Fruitland Park, Florida, were fired or chose to resign over a five-year period from 2009 to 2014 after their Klan membership was discovered. footnote17_bir0x0x46 In 2015, a Louisiana police officer was fired after a photograph surfaced showing him giving a Nazi salute at a Klan rally. footnote18_nhnuqgr47

In 2019, a police officer in Muskegon, Michigan, was fired after prospective homebuyers reported prominently displayed Confederate flags and a framed KKK application in his home. The police department conducted an investigation into potential bias, examining the officer’s traffic citation rate and reviewing an earlier internal affairs investigation into an excessive force complaint and two previous on-duty shootings, each of which were found justified. (The investigation uncovered a third, previously unreported shooting in another jurisdiction that was not further described). footnote19_yrx6gw248 Although the internal investigation documented the officer citing Black drivers at a higher rate than the demographic population in the district he patrolled, it determined that the officer was not a member of the KKK and had shown no racial bias on the job. Still, the report concluded that the community had lost faith in the officer as a result of the incident, and the police department fired him. footnote20_k3ebkmu49 The officer settled a grievance he filed with the Police Officers Labor Council regarding his termination, agreeing to retire in exchange for his full pension and health insurance. footnote21_i48nxxb50

In June 2020, three Wilmington, North Carolina, police officers were fired when a routine audit of car camera recordings uncovered conversations in which the officers used racial epithets, criticized a magistrate and the police chief in frankly racist terms, and talked about shooting Black people, including a Black police officer. One officer said that he could not wait for a declaration of martial law so they could go out and “slaughter” Black people. He also announced his intent to buy an assault rifle in preparation for a civil war that would “wipe ’em off the [expletive] map.” The officers confirmed making the statements on the recording, but they claimed that they were not racist and were simply reacting to the stress of policing the protests following the killing of George Floyd. In addition to the officers’ dismissal, the police chief ordered his department to confer with the district attorney to review cases in which the officers appeared as witnesses for evidence of bias against offenders. footnote22_xael90851

In July 2020, four police officers in San Jose, California, were suspended pending investigation into their participation in a Facebook group that regularly posted racist and anti-Muslim content. In a post about the Black Lives Matter protests, one officer reportedly responded, “Black lives really don’t matter.” In a positive development, the San Jose Police Officers’ Association president vowed to withhold the union’s legal and financial support from any officer charged with wrongdoing in the matter, stating that “there is zero room in our department or our profession for racists, bigots or those that enable them.” footnote23_736n3k652

In some cases, law enforcement officials who detect white supremacist activity in their ranks take no action unless the matter becomes a public scandal. For example, in Anniston, Alabama, city officials learned in 2009 of a police officer’s membership in the League of the South, a white supremacist secessionist group. The police chief, however, determined that the officer’s membership in the group did not affect his performance and allowed him to remain on the job. In the following years the officer was promoted to sergeant and eventually lieutenant. footnote24_l39fd3i53 It wasn’t until 2015, after the Southern Poverty Law Center published an article about a speech he had given at a League of the South conference in which he discussed his recruiting efforts among other law enforcement officers, that the police department fired him. footnote25_zi971hy54 A second Anniston police lieutenant found to have attended the same League of the South rally was permitted to retire. The fired officer appealed his dismissal. After a three-day hearing, a local civil service board upheld his removal. The officer then filed a lawsuit alleging that his firing violated his First Amendment free speech and association rights, but a federal court affirmed the termination.

The Anniston example demonstrates the need for transparency, public accountability, and compliance with due process to successfully resolve these cases. The Anniston Police Department and city officials knew about these officers’ problematic involvement in a racist organization for years, but it took public pressure to finally compel action. They then responded correctly, in awareness of the public scrutiny, by dismissing the officer in a manner that provided the due process necessary to withstand judicial review. The department then implemented a policy requiring police officers to sign a statement affirming that they are not members of “a group that will cause embarrassment to the City of Anniston or the Anniston police department.” footnote26_6e5n0yg55 It requested conflict resolution training from the DOJ Community Relations Service. These were positive steps to begin rebuilding public trust. But as in many of these cases, during the nine years when avowed white supremacist police officers served in the Anniston Police Department (including in leadership positions), there was not a full evaluation or public accounting of their activities. The Alabama NAACP requested that the DOJ and U.S. attorney examine the officers’ previous cases for potential civil rights violations, but there is no evidence that either ever initiated such an investigation. footnote27_9walu4g56 This decision forfeited another opportunity to restore public confidence in law enforcement.

Unfortunately, there is no central database that lists law enforcement officers fired for misconduct. As a result, some police officers dismissed for involvement in racist activity are able to secure other law enforcement jobs. footnote28_owy03nn57 In 2017, the police chief in Colbert, Oklahoma, resigned after local media reported his decades-long involvement with neo-Nazi skinhead groups and his ownership of neo-Nazi websites. footnote29_mfct9ix58 A neighboring Oklahoma police department hired him the following year, claiming he had renounced his previous racist activities and held a clean record as a police officer. footnote30_fzr1uyq59

In 2018, the Greensboro, Maryland, police chief was charged with falsifying records to hire a police officer who had previously been forced to resign from the Dover, Delaware, police department after he kicked a Black man in the face and broke his jaw. The same officer was later involved in the death of an unarmed Black teenager, which sparked an investigation that revealed 29 use of force reports at his previous job, including some that found he used unnecessary force. The previous incidents were never reported to the Maryland police certification board. footnote31_ml7g8cf60

Prosecutors have an important role in protecting the integrity of the criminal justice system from the potential misconduct of explicitly racist officers. The landmark 1963 Supreme Court ruling in Brady v. Maryland requires prosecutors and the police to provide criminal defendants with all exculpatory evidence in their possession. footnote32_04rxk2u61 A later decision in Giglio v. United States expanded this requirement to include the disclosure of evidence that may impeach a government witness. footnote33_2ktn5qr62 Prosecutors keep a register of law enforcement officers whose previous misconduct could reasonably undermine the reliability of their testimony and therefore would need to be disclosed to defense attorneys. This register is often referred to as a “Brady list” or “no call list.”

Georgetown Law Professor Vida B. Johnson has argued that evidence of a law enforcement officer’s explicitly racist behavior could reasonably be expected to impeach his or her testimony. footnote34_4794iz063 Prosecutors, therefore, should be required to include these officers on Brady lists to ensure defendants they testify against have access to the potentially exculpating evidence of their explicitly racist behavior. This reform would be an important measure in blunting the impact of racist police officers on the criminal justice system. In 2019, progressive St. Louis prosecutor Kimberly Gardner placed all 22 of the St. Louis police officers that the Plain View Project identified as posting racist content on Facebook on her office’s no call list. footnote35_b8hqo1t64

Lack of Mitigation Policies to Protect Communities Against Biased Police Officers

The process required to properly address a police officer’s known identification with groups like the KKK or neo-Nazi skinheads, which have decades-long histories of violence, might seem arduous, but these are actually the easy cases. Far more frequently, law enforcement officers express bias in ways that are more difficult for police administrators to navigate.

New white supremacist organizations and other far-right militant groups can often form extemporaneously, then splinter, change names, and employ disinformation campaigns to mask their illicit activities, which makes it difficult to determine whether an officer’s affiliation with a particular group presents a conflict with law enforcement obligations or not. For instance, sheriff’s deputies in Washington State and Louisiana were fired in 2018 for publicly supporting and joining the Proud Boys, a far-right “Western chauvinist” fight club founded in 2016 that disavows racism but often acts in concert with white supremacist groups during violent rallies. footnote1_ckto6hh65 The East Hampton, Connecticut, police department came to a different conclusion about such an affiliation in 2019, however, and determined that an officer who joined the Proud Boys and paid membership fees did not violate department policies and would face no discipline. (The officer claimed to have left the group.) footnote2_9fi7f5o66

Other law enforcement officials do not associate with white supremacist groups, but engage in overtly racist activities in public, on social media, or over law enforcement–only communication channels and internet chat rooms. In a 2019 report, the Plain View Project documented 5,000 patently bigoted social media posts by 3,500 accounts identified as belonging to current and former law enforcement officials. The report sparked dozens of investigations across the country. footnote3_1znr2x567 The Philadelphia Police Department, for example, placed 72 officers on administrative duties pending an investigation into their racist social media activity, ultimately suspending 15 with intent to dismiss. Other officers will face disciplinary action, including suspensions, but will remain on the force. footnote4_lpgyf0w68 Thirteen of 25 Dallas police officers investigated for objectionable social media postings received disciplinary actions ranging from counseling to suspensions without pay. footnote5_0tt1chu69 Only 2 of the 22 current St. Louis police officers identified in the report were terminated. footnote6_6p0eajg70 The St. Louis prosecutor placed all 22 of them on a list of police officers that her office would not call as witnesses, however. footnote7_6jm7hqy71

The San Francisco Police Department attempted to fire nine officers whose overtly racist, homophobic, and misogynistic text messages were uncovered in a 2015 FBI police corruption investigation. After years of litigation, the California Supreme Court finally rejected the officers’ appeal in 2018, which paved the way for disciplinary action to proceed. footnote8_79qsah472 As the case was pending, five other San Francisco police officers were found to have engaged in racist and homophobic texting, at times mocking the investigation of the earlier texts. footnote9_19pd33t73 It is perhaps unsurprising then that in 2016 the Justice Department determined that San Francisco police officers stopped, searched, and arrested Black and Hispanic people at greater rates than white people even though they were less likely to be found carrying contraband. footnote10_wlm8p7u74 In a positive development, when the texting scandal broke in 2015, the San Francisco district attorney established a task force to review 3,000 criminal prosecutions that used testimony by the offending officers, dismissing some cases and alerting defense attorneys to potential problems in others. footnote11_zh7tqt475

In 2019, an internal U.S. Customs and Border Protection investigation revealed that 62 Border Patrol agents, including the agency’s chief, participated in a secret Facebook group that included racist, nativist, and misogynistic material, including threats to members of Congress. footnote12_69ucck376 It is unclear whether disciplinary measures have been taken against these agents. The Border Patrol has tacitly supported vigilante activities by border militia groups on the Southwest border that have demonstrated a propensity for illegal violence over many years. footnote13_87ug1z477

Four Jasper, Alabama, police officers received two-week suspensions for making an “OK” hand signal in a group photograph after a drug bust. The controversial gesture signifies “white power” in the far-right subculture, but is also innocuous and commonplace in other contexts, which provides those who use it with cover to claim benign intentions. footnote14_wel0yak78 In the context of the photograph, the intent of the gesture was clear, but the officers were allowed to remain on the job. footnote15_ofxdhrw79 The mayor of Jasper suggested that the department may require diversity training in the future. footnote16_yn9oxur80

There are cases when an officer’s conduct may indicate bias but does not necessarily justify termination, perhaps because of unclear policies. A photograph of a tattoo on the bare forearm of a Philadelphia police officer caused controversy when observers noted that it resembled Nazi iconography. The officer claimed he was not a Nazi and that the tattoo, which included a stylized eagle and the word “Fatherland,” simply represented his German heritage. footnote17_sys5gbz81 The department, which lacked a specific tattoo policy, cleared the officer of wrongdoing. It subsequently adopted a policy prohibiting “offensive, extremist, indecent, racist or sexist [tattoos] while on duty.” The officer in question was grandfathered in and allowed to remain on the job despite the tattoo, though he agreed to cover it while working. Previously published material linking the officer to a neo-Nazi group was reportedly not considered during the investigation, which determined that he had never “expressed any racial bias on the job.” footnote18_oomq8sj82 The officer’s patrol duties were not altered, leaving members of the community concerned.

When a police department fails to address allegations of officer involvement in white supremacist activities in a timely and transparent manner, it can undermine the public’s perceptions of an entire department, particularly when use of force issues arise. For example, in Portland, Oregon, the National Lawyers Guild filed an excessive force lawsuit against a police officer who pepper-sprayed nonviolent antiwar protesters, including children and a TV camerawoman, in 2002 and 2003. footnote19_9km9ar383 The city of Portland paid $300,000 to settle the lawsuit, but the officer was not disciplined and instead received a promotion. During the lawsuit, however, a whistleblower came forward and alleged that as a young man, the officer was an Adolf Hitler admirer who publicly shouted racist and homophobic rhetoric, vandalized property with Nazi graffiti, dressed in Nazi uniforms, and collected Nazi memorabilia. footnote20_gtuz8op84 A second longtime friend of the officer later confirmed these allegations and contended that the officer had maintained his Nazi ideology while working at the Portland Police Bureau. He provided evidence that the officer had, while working for the police department, illegally erected a memorial to five Nazi soldiers, including one SS officer suspected of war crimes, in a public park. footnote21_xbxg77w85 The officer dismantled the shrine and someone reportedly stashed the plaque in the Portland city attorney’s office, where it remained undiscovered until after the brutality lawsuit had concluded. The officer later claimed that he was not a Nazi but just a “history geek.” footnote22_tg9koqc86

In 2010, the Portland Police Bureau suspended the officer for two weeks for erecting the Nazi shrine. footnote23_43kx2xj87 However, Portland rescinded this disciplinary action in 2014 in order to settle a defamation lawsuit the officer had filed against a superior who called him a Nazi. footnote24_5adt1o788 The officer then continued to be promoted to positions of authority within the bureau.

This history became relevant because the Portland Police Bureau was again accused of bias in its response to a series of violent rallies instigated by far-right militants and white supremacist groups from 2016 through 2019. Portland police and DHS agents appeared inappropriately sympathetic to violent members of the far-right groups, while conducting mass arrests and indiscriminately using less-lethal munitions against antiracist and antifascist counterprotesters. footnote25_hkc493l89 DHS officers were captured on video soliciting the assistance of militia members to arrest antiracist protesters. footnote26_qu67dql90

A draft report of an Independent Police Review investigation into the bureau’s response to the rallies appeared to substantiate these concerns. It quoted a police lieutenant who “felt the right-wing protesters were ‘much more mainstream’ than the left-wing protesters.” footnote27_ikyo0ny91 Allegations of the bureau’s bias surfaced again when Willamette Week, Portland’s alternative weekly newspaper, published friendly text messages between a Portland Police Bureau lieutenant and the out-of-state leader of a far-right group whose members had engaged in violence at these rallies. The texts included advice on how one member with an active warrant could avoid arrest and details about the movements of opposing groups. footnote28_mnqk34e92 The bureau later claimed the texts were intended to gather intelligence and cooperation from the far-right group to prevent violence at the rallies. footnote29_strhaji93 The FBI brought no charges even though several of the violent far-right militants had traveled interstate in order to engage in the rallies.

In May 2019, the Portland City Council hired a private police auditing company to conduct an independent investigation of the police bureau’s response to the far-right protests. footnote30_68ugbxz94 To date, the auditing company has held no public hearings and issued no progress reports.

The Portland Police Bureau was not the only law enforcement agency criticized for its apparent bias as white supremacists and far-right militants engaged in violent protests around the country. California Highway Patrol investigators treated neo-Nazi skinheads who stabbed antiracist counterprotesters at a 2016 Sacramento rally as victims and sought their cooperation in investigating the counterprotesters and a wounded Black journalist. footnote31_7exhc0b95 Police in Anaheim, California, arrested seven antiracism protesters at a KKK rally in 2016, but did not charge the Klansman who stabbed three people. footnote32_t2npp0696

In Huntington Beach, California, park police refused to investigate the battery of OC Weekly journalists by members of the white supremacist Rise Above Movement at a 2017 pro–Donald Trump march, citing a lack of resources. The Orange County district attorney did, however, prosecute an antifascist protester who attempted to defend the journalists by slapping one of the white supremacist attackers. footnote33_606pbum97 The FBI later charged four members of the Rise Above Movement for engaging in violence at a series of riots, including the Huntington Beach attack, but a federal judge dismissed the charges, arguing that the 50-year-old Anti-Riot Act was unconstitutional. footnote34_iu20w0q98

In 2019, a group of Proud Boys in Washington, DC, disrupted a permitted flag burning by members of a communist group in front of the White House, instigating a scuffle. DC police arrested two of the communists but escorted the Proud Boys away. Some officers fist-bumped them as they later walked into a bar. An investigation determined that the officers had not violated any police policies. footnote35_soj035m99

Justice Department Shirks Its Duty to Police Law Enforcement Misconduct

Not only does the U.S. Justice Department fail to properly prioritize investigations of white supremacist violence and hate crimes, it also fails to utilize all necessary resources to address police violence and racism. footnote1_e4acemf100 Federal prosecutors declined to prosecute 96 percent of FBI civil rights investigations involving police misconduct from 1995 to 2015, turning down more than 12,700 complaints, according to a Reuters analysis of DOJ records. footnote2_te8x89j101

Federal prosecutors do face a high evidentiary bar when bringing criminal cases against law enforcement officials, which require proof that the officers willfully intended to violate the victim’s civil rights in their use of force. footnote3_s996inu102 It is not enough to prove that an officer’s intentional use of excessive force resulted in a denial of a victim’s constitutional rights. The civil rights statute that covers police brutality, 18 U.S.C. § 242, requires prosecutors to prove that police officers intended to use excessive force and that they did so with the specific intent to violate the victim’s constitutional rights. footnote4_zg5w16j103

The Justice Department has been delinquent in gathering data about overtly racist police conduct. The lack of a federal database that tracks this type of misconduct or membership in white supremacist or far-right militant groups makes discovering evidence of intent more difficult. The FBI only began collecting data on law enforcement use of force in 2018, after Black Lives Matter and other police accountability groups pushed for more federal oversight of police violence against people of color. footnote5_s2pc8g1104 This is a positive step, but the data relies on voluntary reporting by law enforcement agencies, a methodology which has led to serious deficiencies in hate crime reporting.

In addition to criminal penalties, the Justice Department also has the authority under 42 U.S.C. § 14141 and § 3789d(c)(3) to bring civil suits against law enforcement agencies if it can demonstrate a “pattern or practice” of civil rights violations. footnote6_ji2j5in105 Civil suits have a lower evidentiary bar, but they target department-wide problems rather than individual officers’ misconduct. These cases often reach settlement agreements or “consent decrees,” which provide for a period of DOJ oversight of agreed upon reform efforts. The Obama administration opened 20 pattern and practice investigations of police departments, doubling the number initiated by the Bush administration, and entered into at least 14 consent decrees with police agencies. footnote7_3x1bc92106 The Justice Department has not developed metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of these efforts in curbing police violence or civil rights abuses, however. .footnote8_i03gp6y107

The Trump administration abandoned police reform efforts championed by Obama’s Justice Department. Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered a review of civil rights pattern and practice cases and, on his last day in office, signed a memo establishing more stringent requirements for Justice Department attorneys seeking to open them, which limited the utility of this tool in curbing systemic police misconduct. footnote9_twkacfm108 Sessions also killed a program operated by the DOJ Office of Community Oriented Policing Services that evaluated police department practices and offered corrective recommendations in a more collaborative way that avoided litigation. Attorney General William Barr has indicated similar disdain for law enforcement oversight, once threatening that communities that do not give support and respect to law enforcement “might find themselves without the police protection they need.” footnote10_fadnxhj109

The Justice Department offers civil rights and implicit bias training to law enforcement and often mandates it in consent decrees following pattern and practice lawsuits. While this training may be important to help sensitize law enforcement to unconscious bias, its effectiveness in curbing police bias remains unproven. footnote11_713l0fs110 An obvious deficiency in implicit training sessions is the failure to address overt racism and white supremacy within law enforcement. A police trainer quoted in The Atlantic said overt racism is “just something that you don’t admit. . . . If we admit that, then what does it mean about how we serve the public?” footnote12_wdj17sg111 Another told The Forward, “If [antibias training] is not presented in a very nimble way, officers will assume that what you’re saying is that officers are racist. . . . In my experience, that has tended to close officers up to whatever content you provide.” A third trainer told MSN.com, “When they walk into the classroom, the officers are somewhere between defensive and downright hostile. They think we’re gonna shake our fingers at them and call them racist.” Some studies suggest that implicit bias training can even be counterproductive by reinforcing racial stereotypes. footnote13_kbfob56112

During the June 2019 House oversight committee hearing discussed earlier in this report, Representative Clay asked Deputy Assistant Director Calvin Shivers, who manages the FBI’s civil rights section, whether the bureau provides any resources or training to state and local police departments to help them identify white supremacists attempting to infiltrate their agencies. footnote14_eh3mj75113 Shivers said the training that the FBI’s civil rights section provides to law enforcement is focused on helping them identify hate crimes that may occur within their jurisdictions. He did not identify any training focused on identifying and weeding out officers who actively participate in white supremacist and far-right militant groups.

The continued presence of even a small number of far-right militants, white supremacists, and other overt racists in law enforcement has an outsized impact on public safety and on public trust in the criminal justice system and cannot be ignored. Leaving individual agencies to police themselves in a piecemeal fashion has not proven effective at restoring public confidence in law enforcement. Instead, there should be a comprehensive plan — one that involves federal, state, and local governments — to ensure that law enforcement agencies do not tolerate overtly racist conduct. The final section of this paper proposes several recommendations to include in such a plan.

Protest Policing Reveals Law Enforcement Bias

The police response to nationwide protests that followed the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 includes a number of officers across the country flaunting their affiliation with far-right militant groups. A veteran sheriff’s deputy monitoring a Black Lives Matter protest in Orange County, California, was photographed wearing patches with logos of the Three Percenters and the Oath Keepers — far-right militant groups that often challenge the federal government’s authority — affixed to his bulletproof vest. After an activist group publicized the photograph, the sheriff said it was “unacceptable” for the deputy to wear the patches and placed him on administrative leave pending an investigation. footnote1_19ior04114

A 13-year veteran of the Chicago Police Department is under investigation after photographs surfaced that showed him wearing a face covering with a Three Percenters’ logo while on duty at a protest, though a supervisor was pictured with him at the scene and apparently did not complain. footnote2_79w1d43115 The officer had reportedly been the subject of several previous misconduct lawsuits, including an excessive use of force suit following a nonfatal shooting. The city of Chicago paid $400,000 to settle those suits.

In Salem, Oregon, a police officer was recorded on video asking heavily armed white men dressed like militia to step inside a building or sit in their cars while the police arrested protesters for failing to comply with curfew orders, “so we don’t look like we’re playing favorites.” After a public outcry, the Salem police chief apologized for the appearance of favoritism, but determined the officer was only trying to gain the militants’ compliance with the curfew. footnote3_t2dcgnp116

A police officer in Olympia, Washington, was placed under investigation for posing in a photograph with a heavily armed militia group called Three Percent of Washington. One of the militia members posted the photograph on social media, claiming that the officer and her partner had come over to thank them as they guarded a local shopping center. footnote4_63uuns9117

In Philadelphia, police officers stood by and failed to intervene when mostly white mobs armed with bats, clubs, and long guns attacked journalists and protesters. footnote5_w9qka9u118 The district attorney has vowed to investigate the matter. The following month, however, Philadelphia police officers openly socialized with several men wearing Proud Boys regalia and carrying a Proud Boys flag at a “Back the Blue” party at the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge. footnote6_omz4l2w119

The affinity some police officers have shown for armed far-right militia groups at protests is confounding given that many states, including California, Illinois, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington, have laws barring unregulated paramilitary activities. footnote7_9yrkdcj120 And it is most troubling because far-right militants have often killed police officers. The overlap between militia members and the Boogaloo movement — whose adherents have been arrested for manufacturing Molotov cocktails in preparation for an attack at a Black Lives Matter protest in Nevada, inciting a riot in South Carolina, and shooting, bombing, and killing police officers in California — highlights the threat that police engagement with these groups poses to their law enforcement partners. footnote8_ef83giq121

Recommendations

Federal, State, and Local Law Enforcement Agencies

The failure of federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to aggressively respond to evidence of explicit racism among police officers undermines public confidence in fair and impartial law enforcement. Worse, it signals to white supremacists and far-right militants that their illegal acts enjoy government approval and authorization, making them all the more brazen and dangerous. Winning back public trust requires transparent and equal enforcement of the law, effective oversight, and public accountability that prioritizes targeted communities’ interests.

Where police officers are found to be involved in white supremacist or far-right militant activities, racist violence, or related misconduct, police departments should initiate mitigation plans designed to ensure public safety and uphold the integrity of the law. Mitigation plans could include referrals to prosecutors, dismissals, other disciplinary actions, limitations of assignments to reduce potentially problematic contact with the public, retraining, and intensified supervision and auditing. Law enforcement officials and prosecutors have an obligation to provide defendants exculpating information in their possession, including information about police witnesses’ misconduct that may reasonably impeach their testimony. Prosecutors should include officers known to have engaged in overtly racist behavior to Brady lists. footnote1_g3e8adm122 These lists should be shared among federal, state, and local prosecutors’ offices to ensure fair trials for all defendants in all jurisdictions.

The most effective way for law enforcement agencies to restore public trust and prevent racism from influencing law enforcement actions is to prohibit individuals who are members of white supremacist groups or who have a history of explicitly racist conduct from becoming law enforcement officers in the first place, or from remaining officers once bias is demonstrated. All law enforcement agencies should do the following:

The Justice Department has acknowledged that law enforcement involvement in white supremacist and far-right militia organizations poses an ongoing threat, but it has not produced a national strategy to address it. Not only has the department failed to prosecute police officers involved in patently racist violence, it has only recently begun collecting national data regarding use of force by law enforcement officials. footnote2_zfz2xku123

Congress should direct the Justice Department to do the following:

Lastly, Congress should pass the End Racial and Religious Profiling Act of 2019 to ban all federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies from profiling based on actual or perceived race, ethnicity, religion, national origin, gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Banning racial profiling would mark a significant step toward mitigating the potential harm caused by racist officers undetected within the ranks.

Endnotes

www.brennancenter.org

www.brennancenter.org

.

SUMMARY: The government’s response to

known connections of law enforcement

officers to violent racist and militant groups

has been strikingly insufficient.

The Brannan Center for Justice

By Michael German

August 27, 2020

Introduction

Racial disparities have long pervaded every step of the criminal justice process, from police stops, searches, arrests, shootings and other uses of force to charging decisions, wrongful convictions, and sentences. footnote1_82nauxd1 As a result, many have concluded that a structural or institutional bias against people of color, shaped by long-standing racial, economic, and social inequities, infects the criminal justice system. footnote2_km2l20m2 These systemic inequities can also instill implicit biases — unconscious prejudices that favor in-groups and stigmatize out-groups — among individual law enforcement officials, influencing their day-to-day actions while interacting with the public.

Police reforms, often imposed after incidents of racist misconduct or brutality, have focused on addressing these unconscious manifestations of bias. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), for example, has required implicit bias training as part of consent decrees it imposes to root out discriminatory practices in law enforcement agencies. Such training measures are designed to help law enforcement officers recognize these unconscious biases in order to reduce their influence on police behavior.

These reforms, while well-intentioned, leave unaddressed an especially harmful form of bias, which remains entrenched within law enforcement: explicit racism. Explicit racism in law enforcement takes many forms, from membership or affiliation with violent white supremacist or far-right militant groups, to engaging in racially discriminatory behavior toward the public or law enforcement colleagues, to making racist remarks and sharing them on social media. While it is widely acknowledged that racist officers subsist within police departments around the country, federal, state, and local governments are doing far too little to proactively identify them, report their behavior to prosecutors who might unwittingly rely on their testimony in criminal cases, or protect the diverse communities they are sworn to serve.

Efforts to address systemic and implicit biases in law enforcement are unlikely to be effective in reducing the racial disparities in the criminal justice system as long as explicit racism in law enforcement continues to endure. There is ample evidence to demonstrate that it does.

In 2017, the FBI reported that white supremacists posed a “persistent threat of lethal violence” that has produced more fatalities than any other category of domestic terrorists since 2000. footnote3_hulpaeu3 Alarmingly, internal FBI policy documents have also warned agents assigned to domestic terrorism cases that the white supremacist and anti-government militia groups they investigate often have “active links” to law enforcement officials. footnote4_bu78ixe4

The harms that armed law enforcement officers affiliated with violent white supremacist and anti-government militia groups can inflict on American society could hardly be overstated. Yet despite the FBI’s acknowledgement of the links between law enforcement and these suspected terrorist groups, the Justice Department has no national strategy designed to identify white supremacist police officers or to protect the safety and civil rights of the communities they patrol.

Obviously, only a tiny percentage of law enforcement officials are likely to be active members of white supremacist groups. But one doesn’t need access to secretive intelligence gathered in FBI terrorism investigations to find evidence of overt and explicit racism within law enforcement. Since 2000, law enforcement officials with alleged connections to white supremacist groups or far-right militant activities have been exposed in Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and elsewhere. footnote5_eompaaw5 Research organizations have uncovered hundreds of federal, state, and local law enforcement officials participating in racist, nativist, and sexist social media activity, which demonstrates that overt bias is far too common. footnote6_cj2sx6q6 These officers’ racist activities are often known within their departments, but only result in disciplinary action or termination if they trigger public scandals.

Few law enforcement agencies have policies that specifically prohibit affiliating with white supremacist groups. Instead, these officers typically face discipline, if at all, for more generally defined prohibitions against conduct detrimental to the department or for violations of anti-discrimination regulations or social media policies. Firings often lead to prolonged litigation, with dismissed officers claiming violations of their First Amendment speech and association rights. Most courts have upheld dismissals of police officers who have affiliated with racist or militant groups, following Supreme Court decisions limiting free speech rights for public employees to matters of public concern. footnote7_fcjnjsz7 Courts have given law enforcement agencies even greater latitude to restrict speech and association, citing their “heightened need for order, loyalty, morale and harmony.” footnote8_1maz1dp8

Some officers who have associated with militant groups or engaged in racist behavior have not been fired, however, or have had their dismissals overturned by courts or in arbitration. Such due process is required to ensure integrity and equity in the disciplinary process and protect falsely accused police officers from unjust punishments. Certainly, there will be cases where an officer’s behavior can be corrected with remedial measures short of termination. But leaving officers tainted by racist behavior in a job with immense discretion to take a person’s life and liberty requires a detailed supervision plan to mitigate the potential threats they pose to the communities they police, implemented with sufficient transparency to restore public trust.

Progress in removing explicit racism from law enforcement has clearly been made since the civil rights era, when Ku Klux Klan–affiliated officers were far too common. But, as Georgetown University law professor Vida B. Johnson argues, “The system can never achieve its purported goal of fairness while white supremacists continue to hide within police departments.” footnote9_6eunqy39 Trust in the police remains low among people of color, who are often victims of police violence and abuse and are disproportionately underserved as victims of crime. footnote10_9ru5zm610 The failure of law enforcement to adequately respond to racist violence and hate crimes or properly police white supremacist riots in cities across the United States over the last several years has left many Americans concerned that bias in law enforcement is pervasive. footnote11_i2on4c911 This report examines the law enforcement response to racist behavior, white supremacy, and far-right militancy within the ranks and recommends policy solutions to inform a more effective response.

Inadequate Response to Affiliations with White Supremacist and Militant Groups

The FBI’s 2015 Counterterrorism Policy Directive and Policy Guide warns that “domestic terrorism investigations focused on militia extremists, white supremacist extremists, and sovereign citizen extremists often have identified active links to law enforcement officers.” footnote1_szgn3os12 This alarming declaration followed a 2006 intelligence assessment, based on FBI investigations and open sources, that warned of “white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement . . . by organized groups and by self-initiated infiltration by law enforcement personnel sympathetic to white supremacist causes.” footnote2_7z8mpgh13 Active links between law enforcement officials and the subjects of any terrorism investigation should raise alarms within our national security establishment, but the federal government has not responded accordingly.

The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have identified white supremacists as the most lethal domestic terrorist threat to the United States. footnote3_pbq2b0m14 In recent years, white supremacists have executed deadly rampages in Charleston, South Carolina, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and El Paso, Texas. footnote4_kl6umul15 Narrowly thwarted attempts by neo-Nazis to manufacture radiological “dirty” bombs in Maine in 2009 and Florida in 2017 show their dangerous capability and intent to unleash mass destruction. footnote5_suyrmw116 These groups also pose a lethal threat to law enforcement, as evidenced by recent attacks against Federal Protective Service officers and sheriff’s deputies in California by far-right militants intent on starting the “Boogaloo” — a euphemism for a new civil war — which killed two and injured several others. footnote6_r0sowcx17

Any law enforcement officers associating with these groups should be treated as a matter of urgent concern. Operating under color of law, such officers put the lives and liberty of people of color, religious minorities, LGBTQ+ people, and anti-racist activists at extreme risk, both through the violence they can mete out directly and by their failure to properly respond when these communities are victimized by other racist violent crime. Biased policing also tears at the fabric of American society by undermining public trust in equal justice and the rule of law.

The FBI’s 2006 assessment, however, takes a narrower view. It claims that “the primary threat” posed by the infiltration or recruitment of police officers into white supremacist or other far-right militant groups “arises from the areas of intelligence collection and exploitation, which can lead to investigative breaches and can jeopardize the safety of law enforcement sources or personnel.” footnote7_4n1fidz18 Though the FBI redacted significant passages of the assessment before releasing it to the public, the document does not appear to address any of the potential harms these bigoted officers pose to communities of color they police or to society at large. Rather, it identifies the main problem as a risk to the integrity of FBI investigations and the security of its agents and informants.

In a June 2019 hearing before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, Rep. William Lacy Clay (D-MO) asked Michael McGarrity, the FBI’s assistant director for counterterrorism, whether the bureau remained concerned about white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement since the publication of the 2006 assessment. McGarrity indicated he had not read the 2006 assessment. footnote8_zguc8l119

When asked more generally about the issue, McGarrity said he would be “suspect” of white supremacist police officers, but that their ideology was a First Amendment–protected right. The 2006 assessment addresses this concern, however, correctly summarizing Supreme Court precedent on the issue: “Although the First Amendment’s freedom of association provision protects an individual’s right to join white supremacist groups for the purposes of lawful activity, the government can limit the employment opportunities of group members who hold sensitive public sector jobs, including jobs within law enforcement, when their memberships would interfere with their duties.” footnote9_0hynwu620

More importantly, the FBI’s 2015 counterterrorism policy, which McGarrity was responsible for implementing, indicates not just that members of law enforcement might hold white supremacist views, but that FBI domestic terrorism investigations have often identified “active links” between the subjects of these investigations and law enforcement officials. Its proposed remedy is stunningly inadequate, however. The guide simply instructs agents to use the “silent hit” feature of the Terrorist Screening Center watchlist so that police officers searching for themselves or their white supremacist associates could not ascertain whether they were under FBI scrutiny.

While it is important to protect the integrity of FBI terrorism investigations and the safety of law enforcement personnel, Congress has also tasked the FBI with protecting the civil rights of American communities often targeted with discriminatory stops, searches, arrests, and brutality at the hands of police officers. The issue in these cases isn’t ideology but law enforcement connections to subjects of active terrorism investigations. It is unlikely that the FBI would be similarly hesitant to act if it received information that U.S. law enforcement officials were actively linked to terrorist groups like al-Qaeda or ISIS, or to criminal organizations like street gangs or the Mafia. Yet many of the white supremacist groups investigated by the FBI have longer and more violent histories than these other organizations. The federal response to known connections of law enforcement officers to white supremacist and far-right militant groups has been strikingly insufficient.

A Long History of Law Enforcement Involvement in White Supremacist Violence

White supremacy was central to the founding of the United States, sanctified in law and practice. It was the driving ideology behind the European colonization of North America, the subjugation of Native Americans, and the enslavement of kidnapped Africans and their descendants. Policing in the early American colonies was often less about crime control than maintaining the racial social order, ensuring a stable labor force, and protecting the property interests of the white privileged class. Slave patrols were among the first public policing organizations formed in the American colonies. footnote1_wx7ughf21 Put simply, white supremacy was the law these earliest public officials were sworn to enforce. Even states such as New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois that banned slavery enacted racist “Black laws,” which restricted travel and denied civil rights regarding voting, education, employment, and even residency for free Black people. footnote2_ljelgug22 The U.S. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required law enforcement officials in free states to return escaped slaves to their enslavers in the South. footnote3_ue50urr23

When slavery was finally abolished in the United States after the Civil War, de jure white supremacy lived on through Black codes and Jim Crow laws. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, an openly racist law halting Chinese immigration and denying naturalization to Chinese nationals already living in the United States. footnote4_kfibbk724 The Immigration Act of 1924 was also explicitly racist, codifying strict national origin quotas to limit Italian, eastern European, and nonwhite immigration. The law barred all immigration from Japan and other Asian countries not already excluded by previous legislation. footnote5_1uktj9z25

As the United States expanded westward, government agents enforced policies of violent ethnic cleansing against Native Americans and Mexican Americans. In the early 20th century, Texas Rangers led lynching parties that targeted Mexican Americans residing in Texas border towns on specious allegations of banditry. footnote6_6dw98sy26 Where the laws were deemed insufficient to dissuade nonwhites and non-Protestants from exercising their civil rights, reactionary groups such as the Ku Klux Klan used terrorist violence to enforce white supremacy. Law enforcement officials often participated in this violence directly or supported it by refusing to fulfill their duty to protect the peace and hold lawbreakers to account. By the 1920s, the KKK alone claimed 1 million members nationwide from New England to California, and had fully infiltrated federal, state, and local governments to advance its exclusionist agenda. footnote7_5y6jfun27

Many states outside the Deep South maintained “sundown towns” where police officers and vigilante mobs enforced official and quasi-official policies prohibiting Black (and often other nonwhite) people from remaining in town past sunset. footnote8_byje26c28 Into the 1970s, there were an estimated 10,000 sundown towns across the United States. footnote9_w8ck9l429 Police enforcement of white supremacy was never just a regional problem.

Hidden in Plain Sight

In 1964, civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner went missing in Mississippi during the Freedom Summer voter registration drive, shortly after being released from a Philadelphia, Mississippi, jail where they had been taken to pay a speeding fine. footnote1_56r5dfe30 President Lyndon Johnson ordered FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to send FBI agents to find them. Searchers found the bodies of eight black men, including two college students who were working on the voter registration drive, before an informant’s tip finally led the agents to an earthen dam where Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were buried. After local law enforcement refused to investigate the murders, the Justice Department charged 19 Ku Klux Klansmen with conspiring to violate Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner’s civil rights. Two current and two former law enforcement officials were among those charged. An all-white jury convicted seven of the Klansman but only one of the law enforcement officers. footnote2_slqiz5w31

While the Mississippi Burning case was the most notorious, it was far from the last time white supremacist law enforcement officers engaged in racist violence. There is an unbroken chain of law enforcement involvement in violent, organized racist activity right up to the present. In the 1980s, the investigation of a KKK firebombing of a Black family’s home in Kentucky exposed a Jefferson County police officer as a Klan leader. In a deposition, the officer admitted that he directed a 40-member Klan subgroup called the Confederate Officers Patriot Squad (COPS), half of whom were police officers. He added that his involvement in the KKK was known to his police department and tolerated so long as he didn’t publicize it. footnote3_9amzido32

In the 1990s, Lynwood, California, residents filed a class action civil rights lawsuit alleging that a gang of racist Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies known as the Lynwood Vikings perpetrated “systematic acts of shooting, killing, brutality, terrorism, house-trashing and other acts of lawlessness and wanton abuse of power.” footnote4_plfc5fb33 A federal judge overseeing the case labeled the Vikings “a neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” within the sheriff’s department that engaged in racially motivated violence and intimidation against the Black and Latino communities. In 1996, the county paid $9 million in settlements. footnote5_e3konme34

Recent reporting suggests this overtly racist gang activity within the sheriff’s department continues. footnote6_fjnq9bf35 In 2019, Los Angeles County paid $7 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit against two sheriff’s deputies for shooting an unarmed Black man after testimony revealed that they were part of a group of deputies with matching tattoos in the tradition of earlier deputy gangs. A pending lawsuit accuses the same two officers of beating an unarmed Black man while yelling racial epithets. footnote7_46dl4l836 A Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors investigation revealed that almost 60 lawsuits against alleged members of deputy gangs have cost the county about $55 million, which includes $21 million in cases over the last 10 years. These deputy gangs pose a threat to their fellow law enforcement officers as well, according to two recently filed lawsuits. In one, a deputy alleges he had been bullied by deputy gang members for five years, and finally viciously beaten by the gang’s enforcer. footnote8_3nzwfg837 In another, a deputy who witnessed the attack alleged he suffered threats and retaliation from deputy gang members after reporting it to an internal affairs tip line. footnote9_tqejc0l38 In 2019, the FBI reportedly initiated a civil rights investigation regarding gang activity at the sheriff’s department. footnote10_ce705tl39

Only rarely do these cases lead to criminal charges. In 2017, Florida state prosecutors convicted three prison guards of plotting with fellow KKK members to murder an inmate. footnote11_zmr81zz40 Federal prosecutions are even rarer. In 2019, the Justice Department charged a New Jersey police chief with a hate crime for assaulting a Black teenager during a trespassing arrest after several of his deputies recorded his numerous racist rants. This incident marked the first time in more than a decade that federal prosecutors charged a law enforcement official for an on-duty use of force as a hate crime. footnote12_fzatpjz41 A jury convicted the police chief of lying to FBI agents but was unable to reach a verdict on the hate crime charge, which prosecutors vowed to retry. footnote13_ealooqm42

More often, police officers with ties to white supremacist groups or overt racist behavior are subjected to internal disciplinary procedures rather than prosecution. In 2001, two Texas sheriff’s deputies were fired after they exposed their KKK affiliation in an attempt to recruit other officers. footnote14_msxm58q43 In 2005, an internal investigation revealed a Nebraska state trooper was participating in a members-only KKK chat room. footnote15_mx8o3wy44 He was fired in 2006 but won his job back in an arbitration mandated by the state’s collective bargaining agreement. On appeal, the Nebraska Supreme Court upheld his dismissal, determining that the arbitration decision violated “the explicit, well-defined, and dominant public policy that laws should be enforced without racial or religious discrimination, and the public should reasonably perceive this to be so.” footnote16_a5e6nau45 Three police officers in Fruitland Park, Florida, were fired or chose to resign over a five-year period from 2009 to 2014 after their Klan membership was discovered. footnote17_bir0x0x46 In 2015, a Louisiana police officer was fired after a photograph surfaced showing him giving a Nazi salute at a Klan rally. footnote18_nhnuqgr47

In 2019, a police officer in Muskegon, Michigan, was fired after prospective homebuyers reported prominently displayed Confederate flags and a framed KKK application in his home. The police department conducted an investigation into potential bias, examining the officer’s traffic citation rate and reviewing an earlier internal affairs investigation into an excessive force complaint and two previous on-duty shootings, each of which were found justified. (The investigation uncovered a third, previously unreported shooting in another jurisdiction that was not further described). footnote19_yrx6gw248 Although the internal investigation documented the officer citing Black drivers at a higher rate than the demographic population in the district he patrolled, it determined that the officer was not a member of the KKK and had shown no racial bias on the job. Still, the report concluded that the community had lost faith in the officer as a result of the incident, and the police department fired him. footnote20_k3ebkmu49 The officer settled a grievance he filed with the Police Officers Labor Council regarding his termination, agreeing to retire in exchange for his full pension and health insurance. footnote21_i48nxxb50