Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

HBO Series: Watchmen (2019) (drops 10/20/19) Thread

- Thread starter fonzerrillii

- Start date

Dr Manhattan is in this bitch....

You already know this is going to be good

Man all of these trailers were Fiyah

You already know this is going to be good

Man all of these trailers were Fiyah

Fixed

man. i am about to put that clown on ignore for that comment alone.

supreme trolling.

Now I'm sold this looks wacky and subversive at the same time.

Dr Manhattan is in this bitch....

You already know this is going to be good

Man all of these trailers were Fiyah

Dr Manhattan taught me a lot about life in the Watchmen movie lol

Watchmen really was a beautiful movie

But then it gave us Zach Snyder movies after that and that formula only works with watchmen

My biggest gripe is his ear for scores

Like he fucked wonder woman with her trash score which she had to use in her movie

Just let hans do his thing man

And the slow motion loses impact

Shit by the 3rd matrix they had cut that shut out for the most part

Not Zach tho

Bump for facts

My biggest gripe is his ear for scores

Like he fucked wonder woman with her trash score which she had to use in her movie

Just let hans do his thing man

And the slow motion loses impact

Shit by the 3rd matrix they had cut that shut out for the most part

Not Zach tho

Damon Lindelof to Watchmencreator Alan Moore: 'F--- you, I’m doing it anyway'

By Sydney Bucksbaum

July 24, 2019 at 08:13 PM EDT

FBTwitter

Loaded: 56.53%

YOU MIGHT LIKE

5 DISNEY CLASSICS THAT BECAME MODERN HITS

×

Watchmen

TYPE

But Lindelof isn’t actually trying to start a war with legendary comic writer Moore. When addressing the room of reporters at the summer edition of the Television Critics Association press tour Wednesday, Lindelof explained that Moore’s decision to distance himself from the new adaptation of his graphic novel is “an ongoing wrestling match.”

“I don’t think that I’ve made peace with it,” he said. “Alan Moore is a genius, in my opinion, the greatest writer in the comic medium and maybe the greatest writer of all time. He’s made it very clear that he doesn’t want to have any association or affiliation with Watchmen ongoing and that we not use his name to get people to watch it, which I want to respect.”

ADVERTISING

inRead invented by Teads

MARK HILL/HBO; INSET: ARAYA DIAZ/FILMMAGIC

Despite Lindelof’s “personal overtures” to explain what his new adaption of the graphic novel would be, Moore remains steadfast in his decision to separate himself from the project and won’t consult on the series, a stance that he’s taken for years on the material.

“As someone who’s entire identity is based around a very complicated relationship with my dad, who I constantly need to prove myself to and never will, Alan Moore is now that surrogate,” Lindelof jokes. “The wrestling match will continue. I do feel like the spirit of Alan Moore is a punk rock spirit, a rebellious spirit, and that if you would tell Alan Moore, a teenage Moore in ’85 or ’86, ‘You’re not allowed to do this because Superman’s creator or Swamp Thing’s creator doesn’t want you to do it,’ he would say, ‘F— you, I’m doing it anyway.’ So I’m channeling the spirit of Alan Moore to tell Alan Moore, ‘F— you, I’m doing it anyway.'”

He then immediately followed up with, “That’s clickbait, guys! Clickbait!”

Lindelof did promise, however, that the original source material isn’t being retconned or rewritten in his HBO version. “We reexplore the past but it’s canon,” he says. “Everything that happened in those 12 issues could not be messed with. We were married to it. There is no rebooting it.”

And while fans may be wary of another Watchmen adaptation without Moore’s seal of approval, Lindelof explains that he’s a fan of the original as well.

“All I can say is I love the source material,” Lindelof says. “I went through a very intense period of terror of f—ing it up. I’m not entirely sure I’m out of that tunnel. But I have a tremendous amount of respect for this. I had to separate myself a little bit from this incredible reverence to take risks.”

Watchmen debuts in October on HBO.

By Sydney Bucksbaum

July 24, 2019 at 08:13 PM EDT

FBTwitter

Loaded: 56.53%

YOU MIGHT LIKE

5 DISNEY CLASSICS THAT BECAME MODERN HITS

×

Watchmen

TYPE

- Book

But Lindelof isn’t actually trying to start a war with legendary comic writer Moore. When addressing the room of reporters at the summer edition of the Television Critics Association press tour Wednesday, Lindelof explained that Moore’s decision to distance himself from the new adaptation of his graphic novel is “an ongoing wrestling match.”

“I don’t think that I’ve made peace with it,” he said. “Alan Moore is a genius, in my opinion, the greatest writer in the comic medium and maybe the greatest writer of all time. He’s made it very clear that he doesn’t want to have any association or affiliation with Watchmen ongoing and that we not use his name to get people to watch it, which I want to respect.”

ADVERTISING

inRead invented by Teads

MARK HILL/HBO; INSET: ARAYA DIAZ/FILMMAGIC

Despite Lindelof’s “personal overtures” to explain what his new adaption of the graphic novel would be, Moore remains steadfast in his decision to separate himself from the project and won’t consult on the series, a stance that he’s taken for years on the material.

“As someone who’s entire identity is based around a very complicated relationship with my dad, who I constantly need to prove myself to and never will, Alan Moore is now that surrogate,” Lindelof jokes. “The wrestling match will continue. I do feel like the spirit of Alan Moore is a punk rock spirit, a rebellious spirit, and that if you would tell Alan Moore, a teenage Moore in ’85 or ’86, ‘You’re not allowed to do this because Superman’s creator or Swamp Thing’s creator doesn’t want you to do it,’ he would say, ‘F— you, I’m doing it anyway.’ So I’m channeling the spirit of Alan Moore to tell Alan Moore, ‘F— you, I’m doing it anyway.'”

He then immediately followed up with, “That’s clickbait, guys! Clickbait!”

Lindelof did promise, however, that the original source material isn’t being retconned or rewritten in his HBO version. “We reexplore the past but it’s canon,” he says. “Everything that happened in those 12 issues could not be messed with. We were married to it. There is no rebooting it.”

And while fans may be wary of another Watchmen adaptation without Moore’s seal of approval, Lindelof explains that he’s a fan of the original as well.

“All I can say is I love the source material,” Lindelof says. “I went through a very intense period of terror of f—ing it up. I’m not entirely sure I’m out of that tunnel. But I have a tremendous amount of respect for this. I had to separate myself a little bit from this incredible reverence to take risks.”

Watchmen debuts in October on HBO.

War is brewing in the latest trailer for HBO’s Watchmen, so we’re going to get this out of the way early: We’re on whatever side Regina King’s Angela plays for.

If the reasoning put forth at the beginning of the clip is to be believed, Angela is driven by trauma, obsessed with justice and has experienced grievous injustice in her lifetime. But that doesn’t stop her from donning a mask and kicking down doors in the pursuit of good — even if that means, as she informs Don Johnson’s police chief Judd Crawford, getting a little rough. “There’s a guy in my trunk,” she says, feet kicked up on the desk. And that kind of moxie is going to be valuable if, as Louis Gossett Jr.’s Will Reeves posits, there’s a “vast and insidious conspiracy” afoot.

The new series from Damon Lindelof (The Leftovers) is based on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ graphic novel of the same name and “set in an alternate history where ‘superheroes’ are treated as outlaws.” The limited series promises to embrace the nostalgia of the original groundbreaking graphic novel while attempting to break new ground of its own. The new trailer shows us a bunch of “terrorists” known as the Kalvary, who seem to be targeting police officers like Angela. When one is questioned, we see his interrogator don a mask that seems very similar to that of the comic’s Rorshach, right?

The cast also includes Jean Smart (as Agent Laurie Blake), Jeremy Irons (as “the aging and imperious lord of a British manor,” per the official release), Tom Mison (as Mr. Phillips), Tim Blake Nelson (as Detective Looking Glass), Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (as Cal Abar), Adelaide Clemens, James Wolk, Andrew Howard, Frances Fisher (as Jane Crawford), Jacob Ming-Trent, Hong Chau (as Lady Trieu), Sara Vickers (as Ms. Crookshanks), Dylan Schombing, Lily Rose Smith and Adelynn Spoon.

Damon Lindelof gives his first deep-dive interview for HBO's Watchmen

"I’m not entirely sure I’ll be able to defend every decision I made, but I’ll be able to explain why I made it"

By James Hibberd

September 18, 2019 at 10:02 AM EDT

Robert Redford has been president for 28 years. Cell phones and the internet are outlawed. Fossil fuels are a thing of the past. Costumed heroes were popular, then banned. Police wear masks to protect their identities and cannot use their guns without a dispatcher unlocking them first. Reparations were issued for racial injustice, and our country remains ever divided.

This is the alternate history America of Watchmen, HBO’s upcoming drama series from writer-producer Damon Lindelof (Lost, The Leftovers) that’s a bombastic mix of inspirations from Alan Moore’s “unfilmable” 1986 graphic novel infused with new characters and socio-political themes. “It’s so wildly ambitious and original, it’s like nothing I’ve seen before and also addresses important issues,” says director Nicole Kassell of Lindelof’s scripts.

The story is set three decades after the events in Moore’s Watchmen text. Most of the graphic novel’s iconic characters are apparently dead or in hiding, though a character we suspect is Adrian Veidt, a.k.a. Ozymandius, is kicking around in a mansion (and played with gilded smugness by Jeremy Irons), and the staggeringly powerful Doctor Manhattan is rumored to be hanging out on Mars. The focus instead is on a new character, Angela Abar, an Oklahoma police detective (The Leftovers‘ Regina King) with the secret superhero identity of Sister Night. Abar is investigating the reemergence of a white supremacist terrorist group inspired by the long-deceased moral absolutist Rorschach.

Below Lindelof gives his first in-depth interview about Watchmen, as well as discusses another title for the first time — The Hunt, a film he co-wrote with Nick Cuse that likewise touched on topical political divisions. The Hunt made headlines when it was pulled last month from its planned Sept. 27 release by studio Universal after President Trump and others attacked the film.

Entertainment Weekly: After The Leftovers, you probably could have done whatever you wanted. What made Watchmen right — aside from wanting a very difficult job?

Damon Lindelof: I ask my therapist that question on a weekly basis now. “Why, why Watchmen?” First and foremost this is something I love and something that made a very profound impression on me when I read it when I was 13 years old. In the same way, I wanted to work on a Star Trek movie [Star Trek Into Darkness] and an Alien movie [Prometheus] this is something from my childhood that I carry a tremendous amount of nostalgia for. The fantasy I indulged as a young man was maybe one day I can tell Watchmen stories. The first two times [Lindelof was offered the opportunity to write a Watchmen adaptation] it was incredibly tempting. I said no for various reasons. First and foremost, the timing didn’t feel right — [director Zack Snyder] had just made his [Watchmen] movie. And secondly, revisiting the source material meant adapting something that I knew was so perfect. I knew the best job I could do adapting the original Watchmen was just being a really good cover band.

So is there a way to take this thing I love and be inspired by it, not erase it, but build upon its foundation? That depends on whether I have the right idea. The ideas started to come with what to do with Watchmen and then it didn’t really feel like a decision anymore but something I felt compelled to do. That sounds arrogant and full of hubris but when I haven’t made choices based on that feeling things haven’t turned out so well because then you’re doing it for the wrong reasons. But when you get really inspired you have to chase it even if it leads to ruin.

You’ve said that the project is not a sequel and not a remake but a “remix” and I think some are confused by that. Can we accept that what happened in the comic/film happened in the past of your world? That if we re-read the graphic novel or watch Snyder’s movie that we have a firm handle on what occurred 30 years ago in this story?

Yes. Look, [the new series] certainly fits into the “sequel” box, and definitely doesn’t fit into the “reboot” box. We treat the original 12 issues as canon. They all happened. We haven’t done any revisionist history, but we can maneuver in between the cracks and crevices and find new stories there. But for all the reasons you just articulated, we wanted to make sure our first episode felt like the beginning of a new story rather than a continuation of an old story. That’s what I think a sequel is — the continuation of an old story.

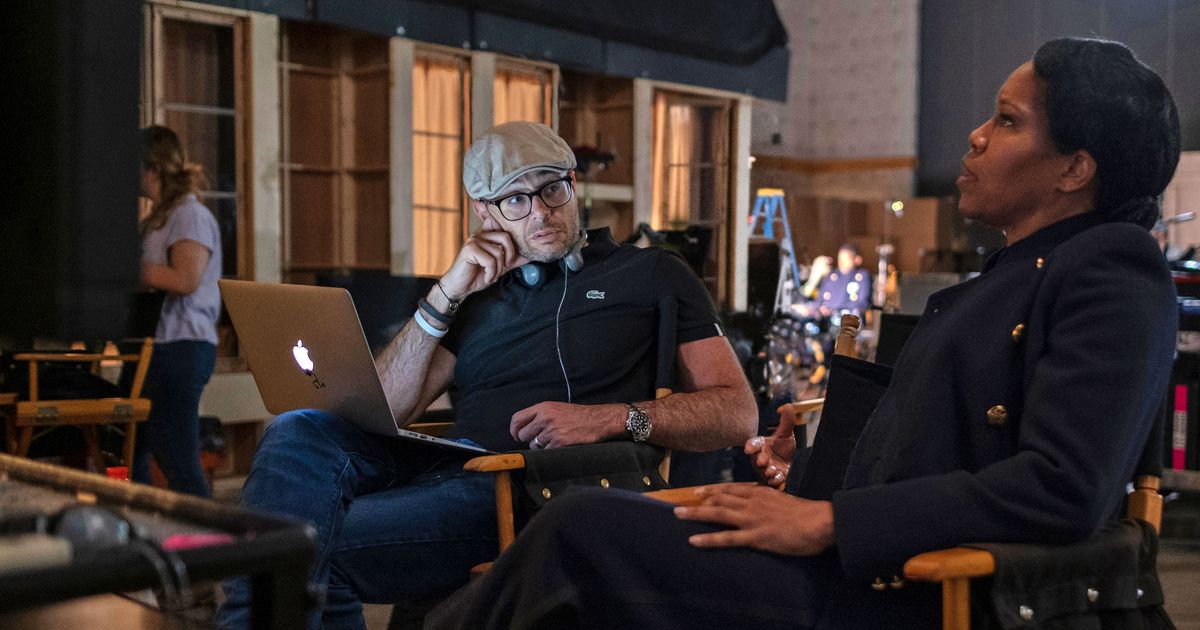

Mark Hill/HBO

After the Television Critics Association press conference this summer, some stories claimed Robert Redford was actually in your show because the president in HBO’s Watchmen for the last 28 years is “Robert Redford.” But the actor is not appearing, right? Were there any concerns about making a real person the president in your show and depicting their real-life liberal ideals as leading to a more totalitarian society without that person actually being involved?

The short answer is yes. I’ve had a lot of reservations about a lot of the creative choices made in the show. I don’t think any of the choices were made without reservations and conversations and ultimately a decision. I’m not entirely sure I’ll be able to defend every decision I made, but I’ll be able to explain why I made it. We had that conversation you’re suggesting. But the world of Watchmen is so heightened and so clearly it’s an alternate history that it will be clear to everyone we’re not talking about the real Robert Redford.

More importantly, the way we handle this story, you can’t blame Robert Redford for everything that’s happened in the world. The show says Redford has a liberal ideology, much like the actual Robert Redford, and he was incredibly well-intentioned in terms of the legislation he passed and the America that he wanted to create. But that doesn’t mean it worked out the way he wanted it to. And that’s not on him, that’s on us.

Can you tell us more about this alternative world beyond the lack of cell phones or Internet — which, of course, are also helpful to eliminate from a screenwriting perspective when telling dramatic stories?

Yes. We’re living in a world where fossil fuels have been eliminated as a power source. All the cars are zero emissions and run on electricity or fuel cells — largely thanks to the innovations of Dr. Mahattan decades earlier. There’s also this legislation that’s passed, Victims Against Racial Violence, which is a form of reparations that are colloquially known as “Redford-ations.” It’s a lifetime tax exemption for victims of, and the direct descendants of, designated areas of racial injustice throughout America’s history, the most important of which, as it relates to our show, is the Tulsa massacre of 1921. That legislation had a ripple effect into another piece of legalization, DoPA, the Defense of Police Act, which allows police to hide their face behind masks because they were being targeted by terrorist organizations for protecting the victims of the initial act. So … good luck sound biting that!

I saw the opening of your pilot depicting the massacre then Googled “Tulsa 1921” and — like you said in another interview — I was surprised and embarrassed that I hadn’t heard of this tragedy before. Why was that incident in particular, and Tulsa in general, the right setting for your story?

Like you just said, my ignorance of the fact that it happened made me feel compelled to educate others. And I could go around to my friends or put it on social media but I feel the biggest platform that’s been afforded me is I get to make television shows that potentially millions are going to watch. And for a show like Watchmen, which already had a built-in audience that has nothing to do with me, to use Watchmen as a delivery mechanism for this piece of erased history felt right as long as it was presented in a non-exploitative way.

Also, the superhero genre always feels like it takes place in New York, Gotham City or Metropolis. And Gotham City and Metropolis are just New York paradigms. So I was like: What does a superhero show look like in Oklahoma? That idea was interesting to me in terms of what it would look and feel like and kinds of people we would populate it with. I also just felt that tickle in my gut that was like, Do it here. That tickle has not always steered me right but it is the thing that makes me do the things I do.

In some ways, there’s also the added challenge of not just doing Watchmen but doing a superhero deconstruction story when there have so many other superhero deconstruction stories in recent years — from Kick-Ass to Deadpool to The Boys. Did that factor into your thinking as well? How do you break new ground on super anti-heroes when even that is now common?

That’s a great question. It’s almost like the truly subversive thing that you could do right now is to celebrate a superhero because the “dark” version, or deconstructed version, is so in the culture. And by the way, in the mid-80s, Watchmen and The Dark Knight both did it, so the idea of deconstructing the superhero myth is 30 years old.

Fully aware of that, I started to think that for Watchmen maybe the more interesting point is to think about masking and authority and policing as an adjunct to superheroes. In Watchmen, nobody has superpowers — the only super-powered individual is Dr. Manhattan and he’s not currently on the planet. In The Boys, you have superpowered individuals in capes that can shoot lasers out of their eyes and fly around and have feats of strength and turn invisible. Nobody on Watchmen can do that. So I felt like we wouldn’t be deconstructing the superhero myth because all the characters in Watchmen are just humans who play dress up. It would be more interesting to ask psychological questions about why do people dress up, why is hiding their identity a good idea, and there are interesting themes to explore here when your mask both hides you and shows you at the same time — because your mask is actually a reflection in yourself. What’s the trauma an individual has that goes into the mask they wear? All that felt Watchmen-y to me. Again, these are not original ideas, but ones I thought were timely when we all have these different identities in code now.

You a sprawling cast. Is there somebody you want to single out who particularly surprised you with their take on they material?

I can’t say enough amazing things about Regina King. The opportunity to make her the star of the show is one of the reasons this was worth doing. It’s not that Regina hasn’t had opportunities to show the world what an incredible actor she is, but to be at the center of the show is a pretty big deal. She’s able to surprise me constantly with her choices as a performer even though I worked with her on The Leftovers for a season and I’ve seen everything she’s she’s ever done going back to 227 and Southland. Yet she’s still able to make choices that make me go, What?

I also want to say that I’m constantly delighted — and I’m not a person that experiences the emotion of delight in my life — by what Jeremy Irons is doing in this show. I’m not only been a fan of his for decades, but I’m just delighted of the choices he’s making.

And that’s not to the exclusion of anything that Jean Smart does, but she’s not introduced until the third episode. Tim Blake Nelson knocks my socks off. And last but not least — and again, there are others I’m not mentioning that are fantastic — Louis Gossett Jr. You don’t get to experience him much in the pilot but starting in the second episode and all through the season he’s a living legend and it was truly a gift to have him say our words.

HBO

I re-read your 2018 Instagram letter to fans about doing a Watchmen series and one line now pops out: “We also intend to revisit the past century of Costumed Adventuring through a surprising yet familiar set of eyes and it’s here we’ll be taking our greatest risk.” Does that refer to the fact that King’s character is an original creation yet the apparent focus of the story? I’m not sure — even after watching the pilot — I know what that means?

Very insightful. You should be in exactly the place that you are at the end of the pilot, which is: “I’m not sure what he’s talking about yet.” By the end of the sixth episode, it will be clear who I was talking about. There won’t be any space for debate. I think people will start to theorize who I was talking about prior to the sixth episode, but that’s the one that makes the subtext text.

Landing Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor as your composer was a big get for a TV show. He’s got such a specific style and the music makes a pretty big impact. What’s that collaboration been like?

It’s Trent and Atticus Ross, they do all their composition work together. We were talking hypothetically about composers and I love the composers that I’ve worked with in the past — like Michael Giacchino on Lost. With The Leftovers, I wanted the show to sound different than Lost so we got Max Richter, who was amazing. When talking about Watchmen, I had to start all over again with somebody I haven’t worked with before because the music is a big part of making shows unique and different from one another. At the top of my wishlist were Trent and Atticus. I called HBO and said, “Look, they haven’t done TV but it’s worth an inquiry.” And [HBO drama executive] Francesca Orsi said, “This is the weirdest thing but their reps called us this morning and asked about Watchmen.” Within 48 hours of that call, Trent and Atticus and I were in a room together and it turns out they’re huge Watchmen fans. They signed up on faith and faith alone. They get the scripts at the same time the actors do. They started writing the music even before we shot the pilot so we can get a sense in our heads of what it would sound like. It’s been incredible. They’re doing some cool stuff I can’t talk about stuff inside the world of Watchmen musically that I think is going to be really cool. They go deep.

I think perhaps your boldest move I’ve heard about so far is Regina said about in an interview we did that you’re not only diving into very hot button topics but you’re handling them in such a way that viewers can read whatever they want into their meaning. You’re avoiding moralizing at a time when popular entertainment is terrified of being misunderstood because there’s such a willingness online to accuse artists of bad intentions. Is that an accurate read? And does that kind of freak you out?

The read is completely accurate and yeah it freaks me out. But when I’m freaked out is when I get excited. I can’t write or create from a nervous scared space. If you stop and try to talk yourself out of doing something that might be upsetting or might make people onerous or confused or uncomfortable you’re never going to do anything interesting. You have to jump in with some degree of forethought and responsibility and then afterward you can ask yourself why you did it. The time for contemplation is not at the edge of the diving board because going back down the ladder is worse than the distance to the pool. I also kind of feel like, unfortunately, we live in a space where hate runs rampant not just on the internet but in real life and it’s important to remind ourselves this is a TV show. It is not real. Although it is dealing with real issues and it’s meant to generate and provoke conversations and emotions we have to contextualize that this is fiction.

That answer could also apply to another of your recent projects, the movie The Hunt (where a group of red-state conservatives are seemingly hunted for sport by liberal elites). From what I gathered from an early version of the script, the film, ironically enough, was attempting to satirize the same sort of divisive online political outrage that led to it being pulled from release. There was a lot of confusion about what the film was actually about. What were you trying to say with that one?

The Hunt is, and always was, a story about what happens when political outrage goes to the most absurd, ridiculous extreme. Because we wanted the movie to be fun and entertaining, we did our very best to make fun of ourselves while making it. The last thing we wanted to do was make a “message” movie. The audience doesn’t want to be preached at so, if anything, this is a story about what happens to folks who deem themselves holier than thou. Spoiler alert: Things don’t turn out great for them.

What was your reaction to Universal canceling the film’s release? Is there a chance of distribution somewhere else?

I’m a TV guy, so I’ve seen many shows “canceled” then revived, so, of course, there’s always a chance the same will happen for us. I understand why the movie was misunderstood, but I really hope people get a chance to see it and make up their minds for themselves.

"I’m not entirely sure I’ll be able to defend every decision I made, but I’ll be able to explain why I made it"

By James Hibberd

September 18, 2019 at 10:02 AM EDT

Robert Redford has been president for 28 years. Cell phones and the internet are outlawed. Fossil fuels are a thing of the past. Costumed heroes were popular, then banned. Police wear masks to protect their identities and cannot use their guns without a dispatcher unlocking them first. Reparations were issued for racial injustice, and our country remains ever divided.

This is the alternate history America of Watchmen, HBO’s upcoming drama series from writer-producer Damon Lindelof (Lost, The Leftovers) that’s a bombastic mix of inspirations from Alan Moore’s “unfilmable” 1986 graphic novel infused with new characters and socio-political themes. “It’s so wildly ambitious and original, it’s like nothing I’ve seen before and also addresses important issues,” says director Nicole Kassell of Lindelof’s scripts.

The story is set three decades after the events in Moore’s Watchmen text. Most of the graphic novel’s iconic characters are apparently dead or in hiding, though a character we suspect is Adrian Veidt, a.k.a. Ozymandius, is kicking around in a mansion (and played with gilded smugness by Jeremy Irons), and the staggeringly powerful Doctor Manhattan is rumored to be hanging out on Mars. The focus instead is on a new character, Angela Abar, an Oklahoma police detective (The Leftovers‘ Regina King) with the secret superhero identity of Sister Night. Abar is investigating the reemergence of a white supremacist terrorist group inspired by the long-deceased moral absolutist Rorschach.

Below Lindelof gives his first in-depth interview about Watchmen, as well as discusses another title for the first time — The Hunt, a film he co-wrote with Nick Cuse that likewise touched on topical political divisions. The Hunt made headlines when it was pulled last month from its planned Sept. 27 release by studio Universal after President Trump and others attacked the film.

Entertainment Weekly: After The Leftovers, you probably could have done whatever you wanted. What made Watchmen right — aside from wanting a very difficult job?

Damon Lindelof: I ask my therapist that question on a weekly basis now. “Why, why Watchmen?” First and foremost this is something I love and something that made a very profound impression on me when I read it when I was 13 years old. In the same way, I wanted to work on a Star Trek movie [Star Trek Into Darkness] and an Alien movie [Prometheus] this is something from my childhood that I carry a tremendous amount of nostalgia for. The fantasy I indulged as a young man was maybe one day I can tell Watchmen stories. The first two times [Lindelof was offered the opportunity to write a Watchmen adaptation] it was incredibly tempting. I said no for various reasons. First and foremost, the timing didn’t feel right — [director Zack Snyder] had just made his [Watchmen] movie. And secondly, revisiting the source material meant adapting something that I knew was so perfect. I knew the best job I could do adapting the original Watchmen was just being a really good cover band.

So is there a way to take this thing I love and be inspired by it, not erase it, but build upon its foundation? That depends on whether I have the right idea. The ideas started to come with what to do with Watchmen and then it didn’t really feel like a decision anymore but something I felt compelled to do. That sounds arrogant and full of hubris but when I haven’t made choices based on that feeling things haven’t turned out so well because then you’re doing it for the wrong reasons. But when you get really inspired you have to chase it even if it leads to ruin.

You’ve said that the project is not a sequel and not a remake but a “remix” and I think some are confused by that. Can we accept that what happened in the comic/film happened in the past of your world? That if we re-read the graphic novel or watch Snyder’s movie that we have a firm handle on what occurred 30 years ago in this story?

Yes. Look, [the new series] certainly fits into the “sequel” box, and definitely doesn’t fit into the “reboot” box. We treat the original 12 issues as canon. They all happened. We haven’t done any revisionist history, but we can maneuver in between the cracks and crevices and find new stories there. But for all the reasons you just articulated, we wanted to make sure our first episode felt like the beginning of a new story rather than a continuation of an old story. That’s what I think a sequel is — the continuation of an old story.

Mark Hill/HBO

After the Television Critics Association press conference this summer, some stories claimed Robert Redford was actually in your show because the president in HBO’s Watchmen for the last 28 years is “Robert Redford.” But the actor is not appearing, right? Were there any concerns about making a real person the president in your show and depicting their real-life liberal ideals as leading to a more totalitarian society without that person actually being involved?

The short answer is yes. I’ve had a lot of reservations about a lot of the creative choices made in the show. I don’t think any of the choices were made without reservations and conversations and ultimately a decision. I’m not entirely sure I’ll be able to defend every decision I made, but I’ll be able to explain why I made it. We had that conversation you’re suggesting. But the world of Watchmen is so heightened and so clearly it’s an alternate history that it will be clear to everyone we’re not talking about the real Robert Redford.

More importantly, the way we handle this story, you can’t blame Robert Redford for everything that’s happened in the world. The show says Redford has a liberal ideology, much like the actual Robert Redford, and he was incredibly well-intentioned in terms of the legislation he passed and the America that he wanted to create. But that doesn’t mean it worked out the way he wanted it to. And that’s not on him, that’s on us.

Can you tell us more about this alternative world beyond the lack of cell phones or Internet — which, of course, are also helpful to eliminate from a screenwriting perspective when telling dramatic stories?

Yes. We’re living in a world where fossil fuels have been eliminated as a power source. All the cars are zero emissions and run on electricity or fuel cells — largely thanks to the innovations of Dr. Mahattan decades earlier. There’s also this legislation that’s passed, Victims Against Racial Violence, which is a form of reparations that are colloquially known as “Redford-ations.” It’s a lifetime tax exemption for victims of, and the direct descendants of, designated areas of racial injustice throughout America’s history, the most important of which, as it relates to our show, is the Tulsa massacre of 1921. That legislation had a ripple effect into another piece of legalization, DoPA, the Defense of Police Act, which allows police to hide their face behind masks because they were being targeted by terrorist organizations for protecting the victims of the initial act. So … good luck sound biting that!

I saw the opening of your pilot depicting the massacre then Googled “Tulsa 1921” and — like you said in another interview — I was surprised and embarrassed that I hadn’t heard of this tragedy before. Why was that incident in particular, and Tulsa in general, the right setting for your story?

Like you just said, my ignorance of the fact that it happened made me feel compelled to educate others. And I could go around to my friends or put it on social media but I feel the biggest platform that’s been afforded me is I get to make television shows that potentially millions are going to watch. And for a show like Watchmen, which already had a built-in audience that has nothing to do with me, to use Watchmen as a delivery mechanism for this piece of erased history felt right as long as it was presented in a non-exploitative way.

Also, the superhero genre always feels like it takes place in New York, Gotham City or Metropolis. And Gotham City and Metropolis are just New York paradigms. So I was like: What does a superhero show look like in Oklahoma? That idea was interesting to me in terms of what it would look and feel like and kinds of people we would populate it with. I also just felt that tickle in my gut that was like, Do it here. That tickle has not always steered me right but it is the thing that makes me do the things I do.

In some ways, there’s also the added challenge of not just doing Watchmen but doing a superhero deconstruction story when there have so many other superhero deconstruction stories in recent years — from Kick-Ass to Deadpool to The Boys. Did that factor into your thinking as well? How do you break new ground on super anti-heroes when even that is now common?

That’s a great question. It’s almost like the truly subversive thing that you could do right now is to celebrate a superhero because the “dark” version, or deconstructed version, is so in the culture. And by the way, in the mid-80s, Watchmen and The Dark Knight both did it, so the idea of deconstructing the superhero myth is 30 years old.

Fully aware of that, I started to think that for Watchmen maybe the more interesting point is to think about masking and authority and policing as an adjunct to superheroes. In Watchmen, nobody has superpowers — the only super-powered individual is Dr. Manhattan and he’s not currently on the planet. In The Boys, you have superpowered individuals in capes that can shoot lasers out of their eyes and fly around and have feats of strength and turn invisible. Nobody on Watchmen can do that. So I felt like we wouldn’t be deconstructing the superhero myth because all the characters in Watchmen are just humans who play dress up. It would be more interesting to ask psychological questions about why do people dress up, why is hiding their identity a good idea, and there are interesting themes to explore here when your mask both hides you and shows you at the same time — because your mask is actually a reflection in yourself. What’s the trauma an individual has that goes into the mask they wear? All that felt Watchmen-y to me. Again, these are not original ideas, but ones I thought were timely when we all have these different identities in code now.

You a sprawling cast. Is there somebody you want to single out who particularly surprised you with their take on they material?

I can’t say enough amazing things about Regina King. The opportunity to make her the star of the show is one of the reasons this was worth doing. It’s not that Regina hasn’t had opportunities to show the world what an incredible actor she is, but to be at the center of the show is a pretty big deal. She’s able to surprise me constantly with her choices as a performer even though I worked with her on The Leftovers for a season and I’ve seen everything she’s she’s ever done going back to 227 and Southland. Yet she’s still able to make choices that make me go, What?

I also want to say that I’m constantly delighted — and I’m not a person that experiences the emotion of delight in my life — by what Jeremy Irons is doing in this show. I’m not only been a fan of his for decades, but I’m just delighted of the choices he’s making.

And that’s not to the exclusion of anything that Jean Smart does, but she’s not introduced until the third episode. Tim Blake Nelson knocks my socks off. And last but not least — and again, there are others I’m not mentioning that are fantastic — Louis Gossett Jr. You don’t get to experience him much in the pilot but starting in the second episode and all through the season he’s a living legend and it was truly a gift to have him say our words.

HBO

I re-read your 2018 Instagram letter to fans about doing a Watchmen series and one line now pops out: “We also intend to revisit the past century of Costumed Adventuring through a surprising yet familiar set of eyes and it’s here we’ll be taking our greatest risk.” Does that refer to the fact that King’s character is an original creation yet the apparent focus of the story? I’m not sure — even after watching the pilot — I know what that means?

Very insightful. You should be in exactly the place that you are at the end of the pilot, which is: “I’m not sure what he’s talking about yet.” By the end of the sixth episode, it will be clear who I was talking about. There won’t be any space for debate. I think people will start to theorize who I was talking about prior to the sixth episode, but that’s the one that makes the subtext text.

Landing Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor as your composer was a big get for a TV show. He’s got such a specific style and the music makes a pretty big impact. What’s that collaboration been like?

It’s Trent and Atticus Ross, they do all their composition work together. We were talking hypothetically about composers and I love the composers that I’ve worked with in the past — like Michael Giacchino on Lost. With The Leftovers, I wanted the show to sound different than Lost so we got Max Richter, who was amazing. When talking about Watchmen, I had to start all over again with somebody I haven’t worked with before because the music is a big part of making shows unique and different from one another. At the top of my wishlist were Trent and Atticus. I called HBO and said, “Look, they haven’t done TV but it’s worth an inquiry.” And [HBO drama executive] Francesca Orsi said, “This is the weirdest thing but their reps called us this morning and asked about Watchmen.” Within 48 hours of that call, Trent and Atticus and I were in a room together and it turns out they’re huge Watchmen fans. They signed up on faith and faith alone. They get the scripts at the same time the actors do. They started writing the music even before we shot the pilot so we can get a sense in our heads of what it would sound like. It’s been incredible. They’re doing some cool stuff I can’t talk about stuff inside the world of Watchmen musically that I think is going to be really cool. They go deep.

I think perhaps your boldest move I’ve heard about so far is Regina said about in an interview we did that you’re not only diving into very hot button topics but you’re handling them in such a way that viewers can read whatever they want into their meaning. You’re avoiding moralizing at a time when popular entertainment is terrified of being misunderstood because there’s such a willingness online to accuse artists of bad intentions. Is that an accurate read? And does that kind of freak you out?

The read is completely accurate and yeah it freaks me out. But when I’m freaked out is when I get excited. I can’t write or create from a nervous scared space. If you stop and try to talk yourself out of doing something that might be upsetting or might make people onerous or confused or uncomfortable you’re never going to do anything interesting. You have to jump in with some degree of forethought and responsibility and then afterward you can ask yourself why you did it. The time for contemplation is not at the edge of the diving board because going back down the ladder is worse than the distance to the pool. I also kind of feel like, unfortunately, we live in a space where hate runs rampant not just on the internet but in real life and it’s important to remind ourselves this is a TV show. It is not real. Although it is dealing with real issues and it’s meant to generate and provoke conversations and emotions we have to contextualize that this is fiction.

That answer could also apply to another of your recent projects, the movie The Hunt (where a group of red-state conservatives are seemingly hunted for sport by liberal elites). From what I gathered from an early version of the script, the film, ironically enough, was attempting to satirize the same sort of divisive online political outrage that led to it being pulled from release. There was a lot of confusion about what the film was actually about. What were you trying to say with that one?

The Hunt is, and always was, a story about what happens when political outrage goes to the most absurd, ridiculous extreme. Because we wanted the movie to be fun and entertaining, we did our very best to make fun of ourselves while making it. The last thing we wanted to do was make a “message” movie. The audience doesn’t want to be preached at so, if anything, this is a story about what happens to folks who deem themselves holier than thou. Spoiler alert: Things don’t turn out great for them.

What was your reaction to Universal canceling the film’s release? Is there a chance of distribution somewhere else?

I’m a TV guy, so I’ve seen many shows “canceled” then revived, so, of course, there’s always a chance the same will happen for us. I understand why the movie was misunderstood, but I really hope people get a chance to see it and make up their minds for themselves.

Watchmen’s Extremist Superhero Dystopia Succeeds on Sheer Nerve

By Matt Zoller Seitz@mattzollerseitz

Photo: HBO

One of the first things you’ll notice about Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen is that the characters who wear masks seem to have trouble keeping them off. The HBO series is a follow-up rather than an adaptation of its source, set in an alternate present, more than three decades after the events of Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins’s industry-realigning 1986 comic — er, graphic novel. Watchmen was ground zero, along with contemporaneous works like Frank Miller’s Ronin and The Dark Knight Returns and Moore’s The Killing Joke, for the “grim and gritty” craze that continues to this day. True to the spirit of those inquisitive, psychology-driven revisionist ’80s works, Lindelof’s series never loses sight of the core question of why people would don masks, even in situations where it’s not important to hide who they are.

Watchmen’s restless dystopia (utopias don’t exist onscreen anymore) is riven by racism and class anxiety, even more so than the present-day United States, and the country seems to have made peace with a mutated version of authoritarian rule — although the fact that the strongman running the country is liberal environmentalist and gun-control advocate Robert Redford, still chugging along after 26 years as president, complicates the analogies to Trump’s America. (Redford is not in the series, but his name is spoken often.) There’s a racially motivated hot war between the guardians of the state and racist elements in the populace, represented by a melting-pot police force that wears masks over the lower parts of their faces to prevent enemies from identifying and murdering them. (The official police masks are bright yellow, evoking the Watchmen series’s insignia, the Comedian’s badge.) The main antagonists are the Seventh Cavalry, a Ku Klux Klan–inspired militia that stockpiles weapons and attacks public officials and institutions while wearing masks inspired by Rorschach, a character from the original comic who was the only vigilante who refused to be employed by the U.S. government. (The use of masks here feels like an escalation of one of Moore’s conceits: The U.S. government banned masked vigilantes in the 1970s.)

It makes sense that Cavalry members would wear masks when carrying out terrorist actions and committing crimes, and that the police would wear their own, often more personalized and makeshift masks while on duty, and while carrying out off-the-books vigilante missions — as when detective Angela Abar (Regina King) decides to capture a suspect in a police shooting without authorization, and puts on the costume of her own alter ego, Sister Night, a flowing hooded cloak and black face paint. But there are many other moments where characters wear them even though they have no apparent reason to, like the police surveillance expert who covers her face while monitoring a Cavalry hideout from inside an armored police hovercraft. And one of Angela’s fellow officers, Looking Glass (Tim Blake Nelson), wears a silvery ski mask with no eyeholes (how does he see?) even when he’s at home watching the news and eating an old-fashioned TV dinner out of an aluminum tin. Sometimes he lifts the mask up so that you can see his eyes, but usually all you get is that distinctively Nelsonian mouth and scraggly whiskers. Does wearing a mask liberate or hide these characters? A bit of both, probably, because people are complicated.

Fans of the source material are either going to love this Watchmen or despise it — the latter, perhaps, because of the selective amnesia afflicting reactionary comic fans who insist that the art form “didn’t used to be political” when it was political from the jump, and progressive more often than not. Moore and Gibbons’s series was released midway through Ronald Reagan’s second term and contained many elements that seemed to warn of latent fascistic tendencies within the United States’ cultural identity, including an obsession with superheroes and supervillains who settled ideological and personal differences through city-leveling mayhem, and often claimed to be acting on behalf of higher principles even when projecting their personal issues onto the world. The series’ storylines concentrate on American discrimination from Watchmen’s opening sequence, a recreation of the 1921 Tulsa riot, in which a white mob destroyed an affluent African-American section of town known as Black Wall Street. (Survivors and descendants of the victims of the Tulsa riots sued for compensation, referred to here as Redfordations.) This theme threads through each successive hour, investing even moments that are theoretically about the characters’ personal lives with a dread of impending racial violence. There’s plenty of the literal kind, including police raids on a Cavalry staging area and a crackdown on a fenced-in trailer park called Nixonville. (There’s a giant statue of the disgraced president out front, both hands raised overhead in a “victory” symbol.) But Lindelof and company invest these and other seemingly straightforward scenes with touches that complicate an easy reading (or just muddle things up). The images of poor whites fenced in by armed police plays into Trump fantasies of the dominant demographic in the U.S. as an embattled minority, beset by deep-state forces and muzzled by political correctness. And for avatars of righteousness, the cops on this show are quite comfortable with torture, which the series portrays as a not merely defensible but effective means of extracting useful information.

While early episodes keep a tight focus on the race war happening on the ground in Tulsa (this is surely the only time that a lavishly budgeted TV fantasy has been set there), Watchmen slowly widens its view to incorporate other characters, some of whom are drawn from the original series. Adrian Veidt (Jeremy Irons), a.k.a. Ozymandias, long missing and officially declared dead, is secretly living in a remote château, where he rides horses, dines in the nude, and is attended to by young servants who double as actors in his plays. The great Jean Smart, fresh off FX’s psychedelic comic-book adaptation Legion, plays an older, more hard-bitten version of Silk Spectre, a crime fighter from the source work. The all-powerful Dr. Manhattan, who left Earth at the end of the original story, is briefly mentioned as living on Mars, and his non-presence here eventually becomes Kurtz-like: You feel his ominous energy even when nobody’s discussing him. Among the new characters, the standout is Angela’s boss, Chief Judd Crawford (Don Johnson), who wears a white hat and professes to have enjoyed an “all-black” local production of Oklahoma! (This is the most charming that Johnson has been since the original Miami Vice — although his casting in this part, as well as the character’s Oklahoma!-derived name, guarantees that the character’s no saint.)

Beyond the embellishments and reimaginings of the source material, the biggest hurdle this Watchmen will face is the way it tells its story. Although each chapter has the feel of a stand-alone, à la The Leftovers, it’s ultimately a highly serialized tale, though one that takes its sweet time easing you into its world and making you work to understand who’s who and what’s actually happening. It’s easy to imagine viewers who aren’t already invested in the very idea of a Watchmen sequel growing impatient with the show’s gradual doling out of exposition; this might turn out to be a case where it’s better to watch the entire thing later, in a single sitting, to see how it all comes together, and to eliminate the feeling that not enough is happening. Still, the sheer nerve of the thing is admirable, as is Lindelof’s determination to make a newish comic-book series that’s bound to be as divisive as the work that sparked his imagination as a teenager.

By Matt Zoller Seitz@mattzollerseitz

Photo: HBO

One of the first things you’ll notice about Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen is that the characters who wear masks seem to have trouble keeping them off. The HBO series is a follow-up rather than an adaptation of its source, set in an alternate present, more than three decades after the events of Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins’s industry-realigning 1986 comic — er, graphic novel. Watchmen was ground zero, along with contemporaneous works like Frank Miller’s Ronin and The Dark Knight Returns and Moore’s The Killing Joke, for the “grim and gritty” craze that continues to this day. True to the spirit of those inquisitive, psychology-driven revisionist ’80s works, Lindelof’s series never loses sight of the core question of why people would don masks, even in situations where it’s not important to hide who they are.

Watchmen’s restless dystopia (utopias don’t exist onscreen anymore) is riven by racism and class anxiety, even more so than the present-day United States, and the country seems to have made peace with a mutated version of authoritarian rule — although the fact that the strongman running the country is liberal environmentalist and gun-control advocate Robert Redford, still chugging along after 26 years as president, complicates the analogies to Trump’s America. (Redford is not in the series, but his name is spoken often.) There’s a racially motivated hot war between the guardians of the state and racist elements in the populace, represented by a melting-pot police force that wears masks over the lower parts of their faces to prevent enemies from identifying and murdering them. (The official police masks are bright yellow, evoking the Watchmen series’s insignia, the Comedian’s badge.) The main antagonists are the Seventh Cavalry, a Ku Klux Klan–inspired militia that stockpiles weapons and attacks public officials and institutions while wearing masks inspired by Rorschach, a character from the original comic who was the only vigilante who refused to be employed by the U.S. government. (The use of masks here feels like an escalation of one of Moore’s conceits: The U.S. government banned masked vigilantes in the 1970s.)

It makes sense that Cavalry members would wear masks when carrying out terrorist actions and committing crimes, and that the police would wear their own, often more personalized and makeshift masks while on duty, and while carrying out off-the-books vigilante missions — as when detective Angela Abar (Regina King) decides to capture a suspect in a police shooting without authorization, and puts on the costume of her own alter ego, Sister Night, a flowing hooded cloak and black face paint. But there are many other moments where characters wear them even though they have no apparent reason to, like the police surveillance expert who covers her face while monitoring a Cavalry hideout from inside an armored police hovercraft. And one of Angela’s fellow officers, Looking Glass (Tim Blake Nelson), wears a silvery ski mask with no eyeholes (how does he see?) even when he’s at home watching the news and eating an old-fashioned TV dinner out of an aluminum tin. Sometimes he lifts the mask up so that you can see his eyes, but usually all you get is that distinctively Nelsonian mouth and scraggly whiskers. Does wearing a mask liberate or hide these characters? A bit of both, probably, because people are complicated.

Fans of the source material are either going to love this Watchmen or despise it — the latter, perhaps, because of the selective amnesia afflicting reactionary comic fans who insist that the art form “didn’t used to be political” when it was political from the jump, and progressive more often than not. Moore and Gibbons’s series was released midway through Ronald Reagan’s second term and contained many elements that seemed to warn of latent fascistic tendencies within the United States’ cultural identity, including an obsession with superheroes and supervillains who settled ideological and personal differences through city-leveling mayhem, and often claimed to be acting on behalf of higher principles even when projecting their personal issues onto the world. The series’ storylines concentrate on American discrimination from Watchmen’s opening sequence, a recreation of the 1921 Tulsa riot, in which a white mob destroyed an affluent African-American section of town known as Black Wall Street. (Survivors and descendants of the victims of the Tulsa riots sued for compensation, referred to here as Redfordations.) This theme threads through each successive hour, investing even moments that are theoretically about the characters’ personal lives with a dread of impending racial violence. There’s plenty of the literal kind, including police raids on a Cavalry staging area and a crackdown on a fenced-in trailer park called Nixonville. (There’s a giant statue of the disgraced president out front, both hands raised overhead in a “victory” symbol.) But Lindelof and company invest these and other seemingly straightforward scenes with touches that complicate an easy reading (or just muddle things up). The images of poor whites fenced in by armed police plays into Trump fantasies of the dominant demographic in the U.S. as an embattled minority, beset by deep-state forces and muzzled by political correctness. And for avatars of righteousness, the cops on this show are quite comfortable with torture, which the series portrays as a not merely defensible but effective means of extracting useful information.

While early episodes keep a tight focus on the race war happening on the ground in Tulsa (this is surely the only time that a lavishly budgeted TV fantasy has been set there), Watchmen slowly widens its view to incorporate other characters, some of whom are drawn from the original series. Adrian Veidt (Jeremy Irons), a.k.a. Ozymandias, long missing and officially declared dead, is secretly living in a remote château, where he rides horses, dines in the nude, and is attended to by young servants who double as actors in his plays. The great Jean Smart, fresh off FX’s psychedelic comic-book adaptation Legion, plays an older, more hard-bitten version of Silk Spectre, a crime fighter from the source work. The all-powerful Dr. Manhattan, who left Earth at the end of the original story, is briefly mentioned as living on Mars, and his non-presence here eventually becomes Kurtz-like: You feel his ominous energy even when nobody’s discussing him. Among the new characters, the standout is Angela’s boss, Chief Judd Crawford (Don Johnson), who wears a white hat and professes to have enjoyed an “all-black” local production of Oklahoma! (This is the most charming that Johnson has been since the original Miami Vice — although his casting in this part, as well as the character’s Oklahoma!-derived name, guarantees that the character’s no saint.)

Beyond the embellishments and reimaginings of the source material, the biggest hurdle this Watchmen will face is the way it tells its story. Although each chapter has the feel of a stand-alone, à la The Leftovers, it’s ultimately a highly serialized tale, though one that takes its sweet time easing you into its world and making you work to understand who’s who and what’s actually happening. It’s easy to imagine viewers who aren’t already invested in the very idea of a Watchmen sequel growing impatient with the show’s gradual doling out of exposition; this might turn out to be a case where it’s better to watch the entire thing later, in a single sitting, to see how it all comes together, and to eliminate the feeling that not enough is happening. Still, the sheer nerve of the thing is admirable, as is Lindelof’s determination to make a newish comic-book series that’s bound to be as divisive as the work that sparked his imagination as a teenager.

Like It or Not, Damon Lindelof Made His Own Watchmen

And he’s pretty sure Alan Moore put a hex on him for doing it.

By Abraham Riesman@abrahamjoseph

Photo: Mark Hill/HBO

It’s January 2017, and Damon Lindelof is profoundly worried. HBO and Warner Bros. have just approached the erstwhile Leftovers and Lost showrunner for the third time about an extremely sensitive topic for geeks: Watchmen. The graphic novel of that name was originally published in serial form by DC Comics in 1986 and 1987 and has subsequently been hailed as one of the greatest superhero stories ever published. It depicts costumed adventurers as narcissistic, violent perverts who leave destruction in their wake, and fans have long admired it as a deconstructionist take on a hoary genre. However, it’s also been a source of great controversy on two fronts. For one, progressive critics have cast aspersions on its portrayal of women, queer people, and people of color.

But more pressing to Lindelof was the second matter, which has to do with creators’ rights. Watchmen was written by Alan Moore and drawn by Dave Gibbons, and the initial plan was for the rights to the book to revert to them after a period of initial publication. However, the Warner-owned DC used a legal loophole to hold onto those rights. An enraged Moore severed ties with DC and has declared his disapproval of all subsequent uses of Watchmen properties, such as a 2009 film adaptation and a 2011 series of prequel comics. (Gibbons has been more cooperative.)

Lindelof is a longtime Watchmen superfan and Moore admirer, so when HBO and Warner asked him to do something with the book on television, he initially refused. They asked again; again, he turned them down. But on that third time … well, he started wondering whether he might be able to do something interesting with it. It was soon after that I received an odd email asking if I’d be willing to speak with Lindelof about a mysterious matter. We scheduled a phone call, during which he explained that he had read a Vulture essay I’d published just a few days prior. DC had started to incorporate Watchmen’s characters into their mainstream superhero universe, meaning they could meet up with Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and the rest of the gang. I thought this was a bad idea.

Lindelof was receptive to that argument and, after swearing me to secrecy, told me about the HBO/Warner offer and asked if I thought it would be a smart to move forward, considering their history with Moore. I told him it was probably unethical, but that if he went through with it, there were ways he could make it interesting. Eight months later, it was announced that Lindelof was making a Watchmen series. Later, he published an open letter (which I offered some pre-publication notes on, per his request) saying the show would not be a straight adaptation, but rather a “remix.” Over the next year, we emailed occasionally about how the series was developing. I was far from a consultant on the show — indeed, I knew no details until I saw media screeners a few weeks ago — but I told him he owed me a big interview before it came out. “A Lindelof always pays his debts,” was his response.

Fast-forward to last week, when I sat in Lindelof’s memorabilia-lined office in Santa Monica for 90 minutes and we talked about Watchmen, both the book and the show. It was an intriguing conversation, revealing Lindelof as a man both proud of what he and his collaborators have made, but also deeply unhappy with his decision to make it in the first place. He’s also pretty sure that Moore, an avowed practitioner of magic, put a curse on him. No, seriously.

How are you feeling?

How I’m feeling, in general, is excitement. It’s very hard not to feel excited when I’m driving around and I see Watchmen billboards with Regina [King]. There’s relief that it’s finally going to be out there. But there’s a lot of fear and trepidation about how it’s going to be processed. Not just the usual “Will people like it?” Obviously, I’ve come to some degree of peace that not everybody is going to like it. It’s not going to be universally loved, especially because it’s Watchmen and especially because it’s about what it’s aboutThe show is explicitly about the struggle against racism and right-wing extremism in America (albeit in an alternate reality).. It’s more a fear of being misunderstood or wondering whether it should have been this. I’m alternately proud of it and second-guessing myself.

The rights to Watchmen, the book, were supposed to revert to Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. But DC Comics screwed them out of that deal and Moore has historically been furious about it, as have readers who advocate for creator rights. What does it feel like to make a show that a lot of people are going to oppose on principle, independent of the quality of the material? Is that something you think about?

That’s something that I think about a lot. What are the ethical ramifications of this even existing at all when I completely and totally side with the creator? Acknowledge that the creator has been exploited by a corporation? Now that very same corporation is basically compensating me to continue this thing.

I ask, “Is it even hypocrisy?” Then I say, as a fan, “Where would I come down on this thing if someone else was doing it? If I heard someone else was doing an HBO series called Watchmen that was not a strict adaptation of the book?” I felt that I’d be really angry about it and then I’d watch it. [Laughs.] I wonder how many of the angry people who don’t think it should exist will actually have the discipline to not even watch it. Those are the people that I really admire. The ones who are like, “This shouldn’t exist and I’m literally not watching it.” That’s an admirable position.

Does it keep you up at night? Or have you made your peace with it?

It wakes me up at night, but much less so now that it’s done. I’m about to say something very ridiculous, but in all sincerity, I was absolutely convinced that there was a magical curse placed upon me by Alan [Moore]Alan Moore has long been open about being a practitioner of magic, particularly magic involving snakes.. I’m actually feeling the psychological effects of a curse, and I’m okay with it. It’s fair that he has placed a curse on me. The basis for this, my twisted logic, was that I heard that he had placed a curse on Zack [Snyder]’s [Watchmen] movie. There is some fundamental degree of hubris and narcissism in saying he even took the time to curse me. But I became increasingly convinced that it had, in fact, happened. So I was like, “Well, at least I’m completely and totally miserable the entire time.” I should be!

When Zack was making Watchmen — and I only know this because I watched the DVDs — I was like, “This guy is having the time of his life!” And I did not enjoy any of this. That’s the price that I paid. Psychological professionals would probably suggest that I emotionally created the curse as a way of creating balance for the immorality.

When we first spoke, you were pretty sure that HBO and Warner Bros. were gonna get someone to do a Watchmen show. You were like, “If it’s me, I can make it as good as it can be so it doesn’t suck.”

That’s hypocrisy, too. It’s like, “Well, I didn’t kill the animal. The steak’s already there. So me not eating the steak doesn’t save it.” It’s a bogus argument to say, “Someone else would have done Watchmen, so it might as well have been me because I loved it the most.” I have to accept the bogusness of that argument and say the truth, which is I just wanted to do it so bad. I wanted to return to the source. This thing that I read when I was 13 years old is what made me. I tried to say “No” twice, but it kept coming back. Twenty years from now, am I going to be regretting that I didn’t do Watchmen because I was scared? If I’m a professional storyteller and I love and revere Watchmen and I spent countless hours of my life thinking about this thing? I wanted to do it.

You keep talking about being miserable; how miserable are we talking here? Was there nothing joyful about putting together the show?

I don’t think it’s fair to say that there was nothing joyful about it. Certainly, the first ten to 12 weeks that we spent in the writers’ room, where we started talking about the vision for the season, that was immensely challenging and not fun. It was work. And, obviously, we’re talking about white supremacy. When you spend hours and hours talking about that stuff, it is supposed to be unpleasant.

There were some days that I came home and I was like, “We had a really good day today.” I was never suicidal. I was never fearful of my life. I don’t like using the word depressed because I know people who are really depressed. That feeling of not wanting to get out of bed and despair and hopelessness — I had all those feelings, but they were attached very specifically to the show. What I was saying to my collaborators on a fairly constant basis was, “This was a huge mistake. I never should have done this. Why did I do this? I can’t quit, I have to see it through, but this was a huge mistake.”

Doesn’t that demoralize people?

Yes.

How did this show get to the finish line, then? How did you manage to power through?

A lot of work that we did in those 12 weeks ended up being the show. Also, the first thing that we did was we wrote all of Jeremy [Irons]’s materialJeremy Irons plays Adrian Veidt, a.k.a. Ozymandias, a mortal but hyper-competent character from the comic, who is portrayed in a surprisingly comic mode in the show.. We went to Wales, and we shot everything, all the way through the finale, for him. He’s not in episode six, but every other episode, you get this Black Freighter–esque interlude. We had to plot all that stuff out and shoot it right after. They picked up the pilot, and then, based on the weather, we were like, “We’ve got to go to Wales. This thing has to be finished shooting by the end of October or things are going to get very inclement, literally and figuratively.”

Jeremy Irons in Watchmen. Photo: HBO

So the Veidt stuff was super-duper fun because we did it first. It gave us a road map. It’s like we had run mile one, mile seven, mile 15, mile 18, mile 21, and mile 26 of the marathon, so it was just kind of connecting the dots. The other part was the material that we were getting back from [shooting in] Atlanta. The stuff that we were getting for [episodes] two and three was like, “Jean Smart is really good. Regina is really amazing. This stuff is working.” As miserable as I was, I’d watch dailies and I’d be like, “That’s pretty cool”

The short answer, now that I’ve monologued about it, is the show stopped feeling like it was mine and it started feeling like it was ours.

Given the racial and gender politics of the show, I didn’t want this to just be a conversation between two white men. So I reached out to a group of women of various ethnic backgrounds who wrote a series of essays called “Women Watch the Watchmen” to ask them what they’d want to ask you. The first question comes from Chloe Maveal: “Do you feel like this show is something that can help redeem Watchmen to literally anyone who’s not part of straight white male audience? Do you, as both a fan of the comics and showrunner of the TV series, feel like the comic books here need redeeming in the first place?”

[Long pause.] I’m only thinking because words are very important. The word redemption is not semantics.

Take your time.

I don’t think that the original Watchmen requires redemption on any level. In any way, shape, or form. I accept it in its totality as a staggering work of art. I also acknowledge that my relationship with Watchmen is that of a hetero straight male who read it as a 13-year-old, which may be the perfect sweet spot. I am not in a place where I can be critical of Watchmen. I am in a place where I can acknowledge criticisms of Watchmen. I will say that a number of the women who worked on Watchmen — wrote Watchmen, produced Watchmen, directed Watchmen — had found the treatment of women in the graphic novel to be less than ideal.

Let’s talk about LaurieLaurie Juspeczyk was a costumed adventurer in the comic. Her father, Eddie Blake, a.k.a. the Comedian, attempted to rape her mother, Sally Jupiter, a.k.a. Silk Spectre, at one point. In the show, she’s played by Jean Smart.. In our presentation of Laurie 30 years later, instead of apologizing for or mocking her younger self, we can show she’s evolved. I think that we were given clues at the end of the original Watchmen — when she says that she wants to get some guns — that she’s feeling this kinship with her dadBlake is a violent, jingoistic, sociopathic bastard whom Laurie despises in the comic, and she only learns about her parentage near the book’s end.. So I’m like, “Instead of casting somebody to play Eddie Blake in flashbacks, what if Laurie is now Eddie Blake?” Not to write her in a masculine way, but to give her that level of nihilism and cynicism. It’s not an idea about redeeming the original Laurie.

Jean Smart in Watchmen. Photo: HBO

We would have Watchmen book club in the writers’ room. Every two or three days, we would unpack an issue. We would argue and debate on areas of ambiguity. I think it’s just fascinating that these characters are so dimensionalized — most of them. You really care about them, but they don’t fit into a very, very simple box. Laurie, I would say, lacked the same level of dimensionality that some of the other male characters in Watchmen do. I would actually argue that Silk SpectreSilk Spectre, a.k.a. Sally Juspeczyk, was a costumed adventurer in the 1930s and ’40s. She is depicted in the comic as a strong-willed, somewhat vain woman who became intimate with Blake, despite his attempted sexual assault., her mom, is fairly dimensionalized. That’s a very provocative idea in 2019, let alone in 1986, that a woman is in love with her rapist. I think, through a certain prism, that idea would require some redemption.

Because I’m not Alan Moore, I get to make a Watchmen that’s like, “Here’s how I feel about female characters. Here’s how I feel about characters of color. Here’s how I feel about Rorschach.” I get to have those debates in the writers’ room. Those other writers get to say, “Well, here’s how I feel about it.” Of course, in the writers’ room, there was a wide range of whether or not Rorschach was a white supremacistRorschach, a.k.a. Walter Joseph Kovacs, is a costumed vigilante with a lethal streak and an unshakeable sense of right and wrong. Speaking of right: He’s profoundly socially conservative and an avid reader of a trashy right-wing magazine. In his diary, he writes about his distaste for queer people and other marginalized groups.. I said, “That’s not relevant. He’s dead. What’s interesting is that you can make a compelling argument that he was and I can make a compelling argument that he wasn’t.”

That gets to a question from Sara Century: “Why is it important to reimagine Rorschach?”

I don’t think that we are reimagining Rorschach. I think that we are interpreting Rorschach. The meta-ness of Watchmen was critical, I think, to its success. This idea of a comic book that is deconstructing comic books, to the degree where a comic book, The Black FreighterThe Black Freighter is a comic that exists within the narrative of Watchmen. It’s about pirates, a topic that became very popular in that world because superheroes never caught on, what with the fact that they were real and therefore somewhat dull., is inside the comic book. You’re actually deconstructing the form. For Veidt to be able to say, “I’m not some Republic Serial villain” with a straight face when he is monologuing about how he just dropped a fake alien squid on New York CityAt the comic’s climax, Veidt unleashes a bizarre assault on New York City wherein he fakes an interdimensional invasion from a giant squid–like creature with psychic powers and deliberately kills 3 million people in the process. The goal is to unite the world at a time when the U.S. and the Soviet Union are about to go to war. and killed 3 million people? That is meta at its most brilliant meta-ness. To that degree, the show is about appropriation. We’re appropriating the original Watchmen. We’re reinterpreting it. We’re saying, “Instead of just being a cover band, we’re going to try to make a new album that is inspired by the original Watchmen and bears its name.”

One of the things that really struck me on my reread of Watchmen, as we were writing the show, was how ineffective Rorschach is. He actually doesn’t accomplish anything. He finds the Comedian costume in Blake’s apartment and then he goes to warn Dr. ManhattanJon Osterman, a.k.a. Dr. Manhattan, is a blue-skinned being from the comic with honest-to-God superpowers, such as the ability to manipulate and destroy matter at will. He is romantically involved with Laurie, but he decides at the end of the book to leave Earth behind. that someone is coming after masks. First off, Dr. Manhattan would know if somebody was coming after him, so Rorschach’s theory is entirely wrong. Then his investigative technique is to just walk into bars and break people’s fingers. He gets suckered by Moloch and gets thrown into jail. DanDan Dreiberg, a.k.a. Nite Owl, is Laurie’s other beau. He’s a nerdy and slightly paunchy costumed adventurer with a lot of gadgets. shows up and gets him away, then he shows up in Karnak too late to stop Veidt’s plan. Then he insists on exposing it all to the one person who he knows is going to kill him. His journal doesn’t out Veidt because everything that he learns in Karnak was not in his journal. So he’s not the brightest bulb. He’s got some very non-progressive views about the world. He’s sad and he’s tragic. At the same time, I love Rorschach. I loved him as a 13-year-old, and I still love him. When you see the tears streaming down his face when his mask is pulled off, one of the cops is saying, “This little runt is wearing lifts.” It just breaks my heart every time. I have such empathy and compassion for this guy who’s losing. The world is sickening, and there’s nothing that he can do to stop it. He’s broken, so he’s going to appeal to broken people.

I worry that the first six episodes, in some ways, can almost be read as a white-supremacist militiaman’s vision of America. Like, “Cops care too much about black people, and they’re cracking down on proud whites like me who just want to see a pure country.” But in reality, the much bigger problem is cops not caring enough about black people. Was that something you thought about? Was that something that worried you?

Yes. I’m not even going to use the past tense. What we’re really worried about, in my opinion, it’s not the television show. What we’re really worried about is a reflection of the real world. The paradox is: How do we feel about the police? When you say “the police,” you can mean it quite literally, which is just people wearing police uniforms. But how do you feel about authority? How do you feel about the law? Is the law just? The answer to the question, “How do you feel about the police?” Well, are you white? Are you a man? Are you a woman? Are you a person of color? What part of the country are you living in? Those are all questions that you should be asking.

We understand that being a police officer is a dangerous job. At the same time, we understand that there are police officers who are not following the law, who cannot be trusted, who do not behave in ways that are demonstrative of equality. This is demonstrated for us over and over again, to the degree where I think anyone who says that there is no issue in the United States in terms of policing and race is a crazy person. That isn’t to say that all cops are racist is any more ridiculous than saying all cops are not racist.