Americans often ask me ‘what is happening?’ in British politics at the moment. Well, here is my answer...

https://spectator.us/brexit-beginners-guide/

Americans, I know you are confused about Brexit. Who isn’t? Even us Brits struggle to keep up with the spats, splits, tensions and bitching Brexit has unleashed across Europe.

Take last week’s Salzburg showdown, at which the heads of the EU’s 28 member states met to gab about immigration, security and, of course, Brexit in a bizarrely done-up hall that looked like the Death Star conference room from Star Wars. The highlight, or lowlight, was a late-night dinner at which Theresa May had 10 minutes to convince the gathered heads to embrace her Chequers version of Brexit. She failed. The side-eye award went to European Council President Donald Tusk who posted on Instagram a photo of himself offering Theresa May a cake with the caption, ‘No cherries’. French President Emmanuel Macron lost le plot and called Brexit leaders ‘liars’. The PM of Malta got the British Twitterati all a flutter by saying the UK should have a second referendum. And May rounded it all off with a tub-thumping speech outside Downing Street upon her return, in which she told off the EU leaders for being rude to her at dinner.

This is, by anyone’s standards, strange stuff. Mean Girls meets European bureaucracy. Social-media burns elevated to the stuff of international debate. It’s little wonder pretty much everyone I meet in the US asks: ‘What’s happening with Brexit?’ Things aren’t helped by the fact that, depending on who and what you Americans read, Brexit is either the worst calamity to hit the West since Hitler (hello, New York Times), or it’s a British version of Donald Trump and everyone who voted for it is a lovely Limey Trumpite (Fox News, etc).

Let’s try to shine some light into this political fog. Here is almost everything Americans need to know about Brexit.

Brexit is the largest act of democracy in British history. 17.4m people voted for it. If you point this out, Remain voters will say: ‘And our vote was the second largest vote in British history!’ This is true. 16.1m Brits voted to remain in the EU and this is the second-largest vote in British history. All sorts of people voted for Brexit, but the poorer you are, the more likely you are to have voted for it. Middle-class anti-Brexit people hate it when you point this out, which makes it great fun. A majority in the lower social classes (C2, D and E) voted Leave, whereas a majority of the highest social class (AB) voted Remain. Yes, we are still obsessed with class.

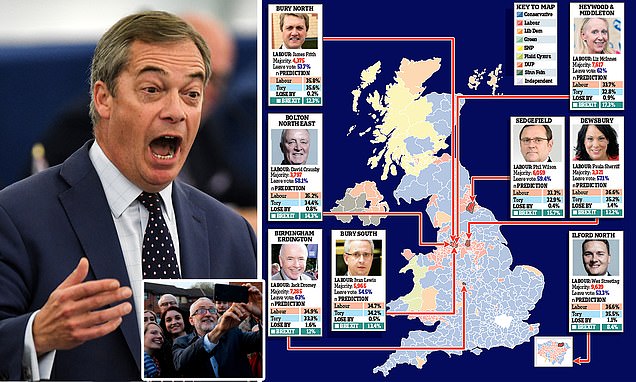

Hardly anyone in the establishment wanted us to vote for Brexit. So we are a great disappointment to them, even more so than normal. More than 70 per cent of MPs voted to remain, as did around 70 per cent of business leaders too, compared with just 48 per cent of everyday Britons. Things are even starker in Labour. Just five per cent of Labour MPs voted to leave the EU, in comparison with 52 per cent of the electorate. It’s worth remembering this next time one of your worthy relatives emails you a Jacobin article or a Bernie Sanders statement about how Jeremy Corbyn’s party is for the many, not the few. It isn’t.

This is why the establishment has been so angry with us these past two years, calling us racist and stupid and whatnot. But this isn’t true. Surveys show people voted for Brexit because they believe decisions about Britain’s future should be taken in Britain rather than in Brussels, not because they want to dismantle the Channel Tunnel and create a wholly white UK.

People still want Brexit. They’re not changing their minds in substantial numbers. Many influential politicians and businesspeople don’t want it, however, and so they are calling for a ‘People’s Vote’. By which they mean a second referendum. And then no doubt a third, and a fourth, and a fifth, until we finally give the ‘right’ answer, at which point they will declare: ‘It’s settled! The people have spoken!’ The leaders of the People’s Vote are rich and influential and most Brits don’t like them very much.

Brexit has ripped up party politics. The biggest divides are now within parties rather than between them. Some Tories are Europhobes, others Europhiles. Labour is split between ‘centrists’ who love the EU and radicals who think we should adhere to the people’s vote (the real one) and leave the EU. Although this week’s Labour conference suggests things might be murkier than that. Many supposedly edgy Corbynistas are now calling for a second referendum, suggesting that for all their Blairphobic bluster they share more in common with Tony Blair, Britain’s No1 Remainiac, than they care to admit. The Tories are led by a lifelong Remainer who now campaigns for Brexit (May), while Labour is led by a lifelong Brexiteer who campaigned for Remain (Corbyn). Are you keeping up?

Then there are the negotiations. These are not going well. This is because the EU is like your Hotel California: you can check out but you can never leave. Brussels is roadblocking Brexit. Its favoured roadblock is Northern Ireland. In order to ensure a ‘soft’ trading border between Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, the whole of the UK should probably stay in the Single Market, it says. Theresa May has offered to kind-of stay in the Single Market — but only for goods, not services — which is far too much of a sellout in the eyes of Brexiteers and not enough of one in the eyes of the EU. ‘Will Brexit ever happen?’, people around the country now ask. Our political class have no idea how irritated these people will be if it doesn’t.

Which brings us back to Salzburg and that lavish dinner at which the leaders of Europe argued the toss over whether Brexit, the largest vote in British history, remember, should be fudged a little (May’s preference) or a lot (the EU’s preference). There’s one good thing about that dinner: it doubles up as a metaphor for why Britons revolted against the EU in the first place.

https://spectator.us/brexit-beginners-guide/

Americans, I know you are confused about Brexit. Who isn’t? Even us Brits struggle to keep up with the spats, splits, tensions and bitching Brexit has unleashed across Europe.

Take last week’s Salzburg showdown, at which the heads of the EU’s 28 member states met to gab about immigration, security and, of course, Brexit in a bizarrely done-up hall that looked like the Death Star conference room from Star Wars. The highlight, or lowlight, was a late-night dinner at which Theresa May had 10 minutes to convince the gathered heads to embrace her Chequers version of Brexit. She failed. The side-eye award went to European Council President Donald Tusk who posted on Instagram a photo of himself offering Theresa May a cake with the caption, ‘No cherries’. French President Emmanuel Macron lost le plot and called Brexit leaders ‘liars’. The PM of Malta got the British Twitterati all a flutter by saying the UK should have a second referendum. And May rounded it all off with a tub-thumping speech outside Downing Street upon her return, in which she told off the EU leaders for being rude to her at dinner.

This is, by anyone’s standards, strange stuff. Mean Girls meets European bureaucracy. Social-media burns elevated to the stuff of international debate. It’s little wonder pretty much everyone I meet in the US asks: ‘What’s happening with Brexit?’ Things aren’t helped by the fact that, depending on who and what you Americans read, Brexit is either the worst calamity to hit the West since Hitler (hello, New York Times), or it’s a British version of Donald Trump and everyone who voted for it is a lovely Limey Trumpite (Fox News, etc).

Let’s try to shine some light into this political fog. Here is almost everything Americans need to know about Brexit.

Brexit is the largest act of democracy in British history. 17.4m people voted for it. If you point this out, Remain voters will say: ‘And our vote was the second largest vote in British history!’ This is true. 16.1m Brits voted to remain in the EU and this is the second-largest vote in British history. All sorts of people voted for Brexit, but the poorer you are, the more likely you are to have voted for it. Middle-class anti-Brexit people hate it when you point this out, which makes it great fun. A majority in the lower social classes (C2, D and E) voted Leave, whereas a majority of the highest social class (AB) voted Remain. Yes, we are still obsessed with class.

Hardly anyone in the establishment wanted us to vote for Brexit. So we are a great disappointment to them, even more so than normal. More than 70 per cent of MPs voted to remain, as did around 70 per cent of business leaders too, compared with just 48 per cent of everyday Britons. Things are even starker in Labour. Just five per cent of Labour MPs voted to leave the EU, in comparison with 52 per cent of the electorate. It’s worth remembering this next time one of your worthy relatives emails you a Jacobin article or a Bernie Sanders statement about how Jeremy Corbyn’s party is for the many, not the few. It isn’t.

This is why the establishment has been so angry with us these past two years, calling us racist and stupid and whatnot. But this isn’t true. Surveys show people voted for Brexit because they believe decisions about Britain’s future should be taken in Britain rather than in Brussels, not because they want to dismantle the Channel Tunnel and create a wholly white UK.

People still want Brexit. They’re not changing their minds in substantial numbers. Many influential politicians and businesspeople don’t want it, however, and so they are calling for a ‘People’s Vote’. By which they mean a second referendum. And then no doubt a third, and a fourth, and a fifth, until we finally give the ‘right’ answer, at which point they will declare: ‘It’s settled! The people have spoken!’ The leaders of the People’s Vote are rich and influential and most Brits don’t like them very much.

Brexit has ripped up party politics. The biggest divides are now within parties rather than between them. Some Tories are Europhobes, others Europhiles. Labour is split between ‘centrists’ who love the EU and radicals who think we should adhere to the people’s vote (the real one) and leave the EU. Although this week’s Labour conference suggests things might be murkier than that. Many supposedly edgy Corbynistas are now calling for a second referendum, suggesting that for all their Blairphobic bluster they share more in common with Tony Blair, Britain’s No1 Remainiac, than they care to admit. The Tories are led by a lifelong Remainer who now campaigns for Brexit (May), while Labour is led by a lifelong Brexiteer who campaigned for Remain (Corbyn). Are you keeping up?

Then there are the negotiations. These are not going well. This is because the EU is like your Hotel California: you can check out but you can never leave. Brussels is roadblocking Brexit. Its favoured roadblock is Northern Ireland. In order to ensure a ‘soft’ trading border between Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, the whole of the UK should probably stay in the Single Market, it says. Theresa May has offered to kind-of stay in the Single Market — but only for goods, not services — which is far too much of a sellout in the eyes of Brexiteers and not enough of one in the eyes of the EU. ‘Will Brexit ever happen?’, people around the country now ask. Our political class have no idea how irritated these people will be if it doesn’t.

Which brings us back to Salzburg and that lavish dinner at which the leaders of Europe argued the toss over whether Brexit, the largest vote in British history, remember, should be fudged a little (May’s preference) or a lot (the EU’s preference). There’s one good thing about that dinner: it doubles up as a metaphor for why Britons revolted against the EU in the first place.