http://www.espn.com/espn/feature/st...ement-endures-supporters-more-fragmented-ever

A Protest Divided

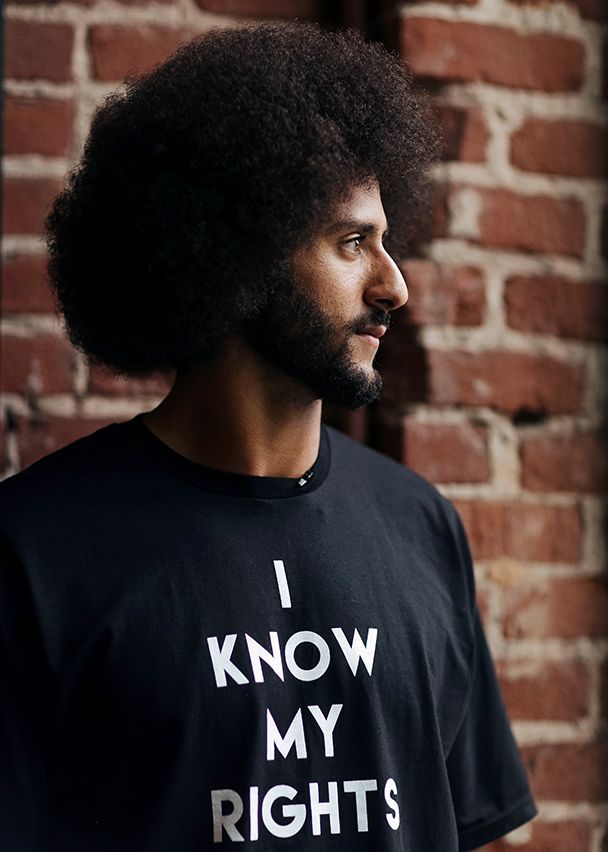

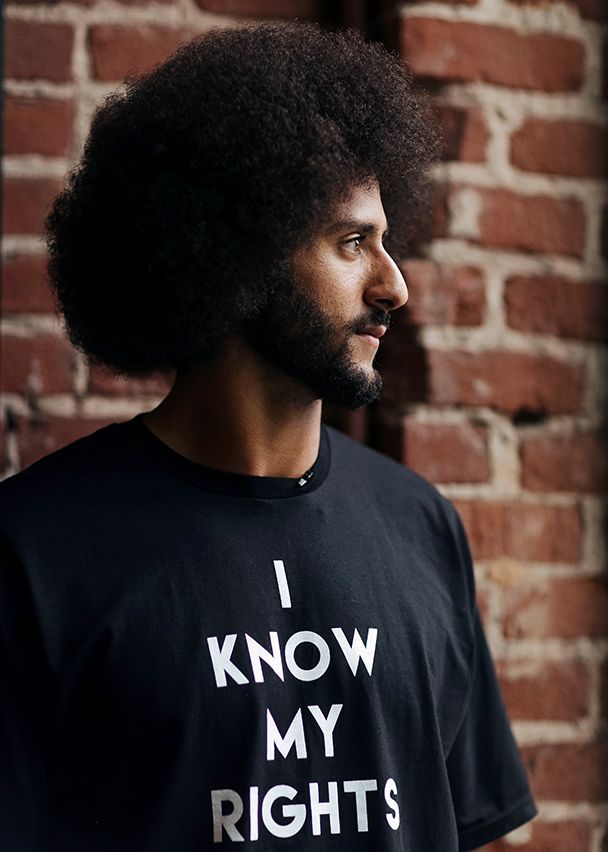

The movement started by Colin Kaepernick endures, but its supporters are more fragmented than ever. This is the inside story of how infighting splintered a group of players once unified in its pursuit of a cause bigger than themselves.

by Howard Bryant

01/26/18

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Feb. 5 State of the Black Athlete issue. Subscribe today!

Forty-niners safety Eric Reid's instincts were buzzing as if he were anticipating a screen pass. Increasingly, they were telling him to expect the worst. For weeks during the fall of 2017, tension had been brewing within the Players Coalition, a collection of NFL players committed to addressing issues of social justice. Under scrutiny from fans, owners and even the president of the United States over recent protests during the singing of the national anthem, the players found themselves fluctuating between solidarity and fracture as they struggled to unify their message and leverage their position for change.

On Nov. 29, Reid received a text from one of the leaders of the coalition, Eagles safety Malcolm Jenkins, about Jenkins' discussions with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell and the league's player liaison, Troy Vincent. At issue was how the players could partner with owners on initiatives within the African-American community. The two sides had discussed the league making a huge donation to social justice causes. Jenkins' text to the group concluded with: "If they were to agree to this, do you think you'd be more comfortable with ending the demonstrations?" Reid believed that Jenkins -- without consent of the group -- had volunteered to end their protest in exchange for a financial commitment from the NFL.

"My head was ready to explode," Reid recalls. "I was already drifting from the coalition, and this confirmed why."

To Jenkins, financial commitment from the owners was a positive step, a pathway to putting real resources toward fighting the injustice that fueled their demonstrations. But to Reid, who had been kneeling during the national anthem since the protests began in September 2016, alongside former teammate Colin Kaepernick, the deal felt like a payoff to stop kneeling -- the final betrayal in what had been a tense season. Not long after receiving Jenkins' text, feeling sold out, Reid released a statement that he was quitting the coalition.

A few days later, the NFL said it would pledge $89 million over seven years to grassroots social justice groups, to be matched by the players. Jenkins said the NFL's money did not preclude other players from protesting if they chose, but he would no longer be demonstrating during the anthem. Yet while former player Anquan Boldin, a key member of the coalition, told the New York Daily News that "I think the NFL got it right," the deal served as a breaking point for others.

Dolphins safety Michael Thomas, who had continued to kneel during the anthem, followed Reid out of the group. Chargers lineman Russell Okung called the deal a "farce."

For Reid and other defecting players, the coalition had become the NFL's hand-picked safe alternative to Kaepernick and the kneeling players; the league had lured them with promises of social commitment and big money to cover for the real purpose of sabotaging their movement and ending the protests. The coalition, meanwhile, was insulted by the idea it had sold out, and there was heavy sentiment within the coalition and the union that Kaepernick had squandered his opportunity. They also believed that his allies, while admirable in their idealism, were impractical about how to get things done. "It's unrealistic to think everyone was going to see eye to eye, but I am encouraged the coalition is alive and well," Jenkins says. "We have a ton of players that are super interested and excited to get to work to highlight the work they've already been doing."

With the season now nearly over, a group of socially committed players remains at odds -- with Kaepernick as the dividing line. Interviews over four months with multiple players, representatives and league insiders show how the cause Kaepernick started has been slowly fractured by frustrations, unreconciled resentments and missed opportunities to fight for real change -- a potentially unifying movement that fell apart for reasons that to some observers seem inevitable in retrospect.

"The players had real leverage," an NFL owner says. "But we knew we could sit back and watch them implode."

TO UNDERSTAND THE current player division, it's important to first understand how each faction dealt with Kaepernick's unemployment.

Kaepernick had every intention of playing in the NFL this season. When the 49ers told him that they would cut him if he opted into his $14.5 million contract, after he had thrown for 2,241 yards in 11 starts in 2016, he opted out a week early, in March 2017, to get a jump on the marketplace. He knew his season-long protest during the anthem -- which he began in the final preseason game of 2016 -- had created an enormous negative for coaches and owners. So he and his team of advisers, led by agent Jeff Nalley (who declined to be interviewed for this story), set a strategy for dealing with the issue: He would grant no interviews about the NFL. "If you say nothing, nothing can be used against you," Kaepernick told me during a July interview for an upcoming book.

The possibility that there would be repercussions for his protest, however, was never far from the minds of his advisers -- or the NFL Players Association. Following the Super Bowl last year, the union reached out to Kaepernick's team to inquire about formulating a collusion case in anticipation that he'd be frozen out of the league. Kaepernick's advisers declined, wanting to approach the free agent and draft periods with an open mind. As the calendar turned and quarterbacks with lesser pedigrees were signed, Kaepernick waited. Criticism mounted from members of the media, teams and even fellow players and union insiders over Kaepernick's decision to opt out of his deal instead of forcing the 49ers to release him, yet he still chose not to respond. (Kaepernick has not conducted a formal news conference or television interview in over a year.)

By summer's end, his support team looked with optimism toward the first month of the season. Certainly, his advisers reasoned, a contender with a hole under center would tap him as a veteran replacement. They reasoned incorrectly. Indianapolis had been in limbo throughout training camp with the injured Andrew Luck but then acquired Jacoby Brissett from the Patriots. The Broncos' quarterback situation was a mess, but the team decided to sign Brock Osweiler, a Browns castoff who had started in Denver previously. When Ryan Tannehill went down in Miami, the team lured Jay Cutler out of retirement with $10 million. The humiliations mounted. Still, Kaepernick said nothing.

Simmering through all this were what Kaepernick's advisers deemed a series of major slights by the union, dating to Aug. 31, 2016, when a story by Mike Freeman of Bleacher Report contained this passage: "One executive said he hasn't seen this much collective dislike among front office members regarding a player since Rae Carruth. Remember Rae Carruth? He's still in prison for the plot to murder his pregnant girlfriend."

That sentiment bothered Kaepernick, but it did not bother him nearly as much as what occurred after: silence from the NFLPA and its executive director, DeMaurice Smith.

"How could they f---ing let that pass? Nobody defended him," says one member of Kaepernick's inner circle. "You just let them compare one of your players, who had done nothing except try to help some of the most vulnerable people in this country ... you let them compare him to a f---ing murderer?" (Carruth was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and two other charges.) According to a union source, the NFLPA had a different focus at the time: "We're concerned with the legal aspects of this case, and they want us to make them feel better."

The Kaepernick team did want them to make their guy feel better. No one had risked more than Kaepernick, and no one was losing more. The least the union could do, members of Kaepernick's team thought, was provide a fierce, public shield of support.

Meanwhile, civil rights leader Al Sharpton attempted to mobilize his National Action Network to organize a boycott of the NFL on Sept. 10 -- opening Sunday -- if Kaepernick remained unsigned. But Sharpton had two problems, both of which spoke to the growing tensions among the protesters. The first was the fact that the players seemed prepared to play without a formal response to Kaepernick's situation; they had planned no gesture of solidarity via a news conference or an on-field action on behalf of Kaepernick. "How much can we be expected to do when these players are willing to sacrifice one of their own?" Sharpton said a month before the regular season began.

Sharpton's second problem was Kaepernick. According to Sharpton, Kaepernick's camp ignored his overtures during the spring and summer as fans organized spontaneous boycotts supporting the quarterback. The moment was slipping away. "We want to help," Sharpton said. "There's a feeling that people with buying power don't support him, and believe me, we can show the NFL that plenty of black people with buying power do support him. All he has to do is say the word and we'll get 10,000 people out in front of NFL headquarters or wherever he wants to go, but I don't know what his strategy is. Does he have a strategy?"

AS QUESTIONS WERE being raised about Kaepernick's silence, the NFLPA was wrestling with its own strategy for how to deal with protesting players. It supported the players' right to demonstrate (a dozen players did so on opening day in 2016), but the union believed its primary responsibility wasn't to eradicate police brutality- but to protect jobs and increase salaries -- and if sponsors distanced themselves from the league, it would shrink the financial pie for players. But the thorniest issue was that it was impossible to know if there was universal player support -- from a membership of nearly 2,000 -- for the on-field demonstrations.

Over a year after Kaepernick first took a knee, it still perplexes Smith that the union could be accused of not being supportive. Smith says he had decided the most important thing he could do after the quarterback's August 2016 protest was to maintain the right of the players to protest at work, and so he gave an interview to Dave Zirin of The Nation in which he defended that right. When the league did not move to punish Kaepernick, Smith believed he had protected his player. Combined with the NFLPA's expressed willingness to mount a collusion case, Smith believes that refutes the notion that the union was lukewarm to Kaepernick's cause.

Yet the stalemate between Kaepernick and the NFLPA deepened this season. In early September, Kaepernick's representatives flew to Washington to meet with the union's legal team, general counsel Tom DePaso and senior director of player affairs Don Davis. Both sides agreed to remain in contact and strategize as the season progressed, but now, months later, each side alleges the other never called back. Kaepernick's team says that it asked Smith to write a public statement charging the NFL with collusion but that Smith refused. According to a union source, the reason the union didn't publicly accuse the owners of collusion was that it would have immediately started a statute of limitations on a collusion action, which would have undercut the union's position.

Then came the moment that changed the season: President Donald Trump's Sept. 22 speech in Huntsville, Alabama, during which he turned his focus on the player protests. "Wouldn't you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, 'Get that son of a bitch off the field right now? Out. He's fired! Fired!'"

For the first time in a year, the players had a cause that could band them together as a union. In the week after, white and black players knelt, shot their fists into the air and locked arms. Even Dallas owner Jerry Jones took a knee before an anthem.

"[Kaepernick] did such a brave thing, such a selfless thing, that has resulted in other guys doing a selfless thing, and it reached the president of the United States," Smith says. "And it pissed off some sponsors, media and fans, but it took back the curtain, and our players got to see these people for what they truly were, and it made our union stronger. It allowed me to say the same thing to all 32 teams: All of you responded with more respect than the president gave you. The best conversations about race, inequality and social justice were occurring in a room of quote-unquote millennials where people on the outside think of you as insular, self-centered and inattentive."

But even with the momentum shifting toward the players, discord simmered. The original group of dissenters -- kneelers such as Reid, Eli Harold of the 49ers and Kenny Stills of the Dolphins -- was concerned its movement was being smothered by the president's spectacle. Were the protests about Trump or the recent violence in Charlottesville? And while everyone was patting himself on the back for taking a stand, they pointed out, Kaepernick was still unemployed.

Two weeks later, high-profile defense attorney Mark Geragos filed a formal charge of collusion on behalf of Kaepernick against the NFL. What was felt privately in his camp all spring and summer could now be said out loud: Kaepernick believed he was being blackballed by the NFL.

The next obvious step was for Kaepernick's team and the union to begin working together on their case. But according to both the NFLPA and Kaepernick's legal team, when NFLPA counsel texted Kaep-ernick requesting that he meet with Smith, Kaepernick rebuffed the idea. He told them to talk to his lawyers, who were handling the case. Kaepernick's advisers saw the response as standard. The union was insulted. The bad blood increased.

AS EARLY AS the 2017 preseason, Malcolm Jenkins had been in talks with Goodell about partnering with the NFL on criminal justice initiatives. For two seasons, he'd raised his fist in the air during the anthem -- a nod to the iconic 1968 Summer Olympics protest of John Carlos and Tommie Smith -- and did work off the field with congressional leaders, local police and community organizers. In 2016, along with Boldin, he formed the advocacy group that would become the Players Coalition, growing it to roughly 50 players over the following year and a half. (Reid joined in September 2017.) Along the way, they engaged Goodell and Vincent about ways the league and players could partner on issues important to the players. Jenkins had always wanted the movement to be player-led, with minimal input from the union.

"It showed the convictions of the players, it showed the intelligence of the players, and quite frankly, we kept the PA at bay," Jenkins says. "They didn't want us in a room talking to the league, but we were going to do it anyway. So they came along to make sure things went smoothly." The coalition first met with the owners in New York in late September. Jenkins, Reid and several other players attended. Reid described it as a "dance," in which talk of common ground persisted without substantial result. The second meeting, in Washington a few weeks later, contained even more tension, according to multiple players and union members who were there. Goodell attended with owners John Mara of the Giants, Art Rooney II of the Steelers and Robert Kraft of the Patriots. Representing the players were Smith, Washington's Josh Norman and Kirk Cousins, the Jets' Demario Davis and the Eagles' Chris Long. The players told the owners they appreciated their willingness to work together but chastised their lack of public support in the face of Trump's criticism.

Norman referenced the league's domestic violence crises and how quickly the NFL sprang into action, contrasting that to the time it was taking to address players' current concerns. Jenkins and NFLPA president Eric Winston both mentioned how much money in campaign contributions owners gave to Trump, which to them explained why they allowed him to savage the players.

Smith didn't hold back either. "You've been fine with the players being out front on this issue," he said at one point, "and you were happy with our players taking a beating from the right and being characterized as anti-cop, anti-America, anti-military, and that's bulls -- t."

At another juncture, Long recalls making a different point to the owners, which was then echoed by other players: "We haven't forgotten Kaep doesn't have a job. He deserves a job."

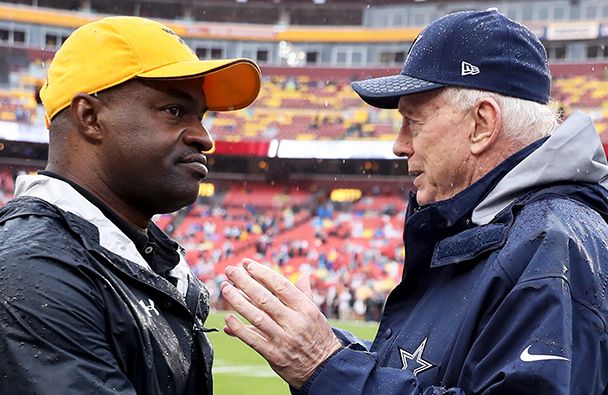

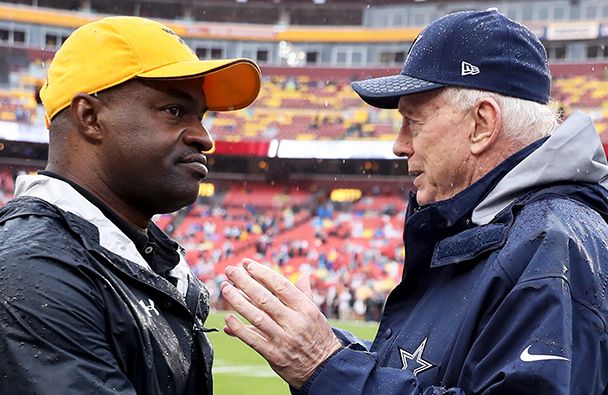

Over a year after Kaepernick first took a knee, it still perplexes DeMaurice Smith, pictured here talking to Jerry Jones, that the union could be accused of not being supportive. ROB CARR/GETTY IMAGES

FOR A FEW weeks between late October and early November, the players appeared unified; in group chats and phone calls, they discussed strategy for negotiating with the owners. Through Reid, Kaepernick was kept up to speed, and Kaepernick soon agreed to join the coalition.

But the coalition was fracturing along a tenuous line. Players like Reid, who primarily protested by taking a knee and who believed their protest was directly linked to Kaepernick's employment, saw themselves as taking the greatest risk. Kaepernick was out of the league, as was longtime veteran defensive back Antonio Cromartie, who had taken a knee to start 2016 and was cut after four games by the Colts. Reid himself was in a contract year. And although Jenkins maintained that all the players in the coalition could offer input on a massive group text-messaging chain, the kneelers felt as if they had nominal influence.

Reid had been wary of the coalition dating to the first New York meeting, when, as ESPN The Magazine previously reported, Bills owner Terry Pegula suggested that Boldin would be the perfect NFL spokesman on social issues, in part because it couldn't be a "white owner but needs to be someone who's black." Reid suggested Kaepernick. "If there's going to be a face to this, it needs to be Colin," Reid recalls saying. The room did not respond.

The kneelers didn't feel particularly supported by the union either. In early October, when Jerry Jones threatened to bench any Cowboys player who demonstrated, Reid called Smith, asking him what the union response would be. "You just heard a guy blatantly threaten our job security," Reid remembers saying, "and you're not going to respond?" Smith said he already had Goodell's assurances that players would not be punished for protesting, as well as the assurance of Giants owner John Mara, one of the game's most powerful brokers. "It's healthy for us to have tough discussions and even disagree at times," Smith says now. "We will be taking measures this offseason to work with agents and the league to make sure players know their rights and clubs respect the rights we all agreed are protected."

But personal animus lingered after Jones' threat. There was jousting between Kaepernick and Jenkins about leadership of the coalition. Reid says the group had agreed that there would be an inclusive leadership structure, yet he felt that Jenkins had annointed himself the leader of the coalition. Meanwhile, Jenkins says his only goal was to have players united to fight issues important to them -- he was moved to action when police killed Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, the same as Reid and Kaepernick. "We got to this moment, we're all here for the same reason," he says, "and that is we want to see change in our communities, especially black communities. The goal isn't the protest. The goal is to move beyond the protest and make some changes."

The divide grew when Geragos went public about Kaepernick not being invited by the players to the October New York meeting. According to two players in the group, Jenkins and other members of the coalition did not like Kaepernick "lawyering up."

On Oct. 28, Jenkins sent a message to the group chat that read, "Heads up guys. I removed Kap from this chat. His attorneys have been contacting me and it seems clear to me that he is not interested in working under the Coalition. I think it's important that we keep him involved in what we do and he will still be invited to meetings that we have. But in regards to our decision making and communications between members of the Coalition, I think it's important to keep these things in house in the spirit of solidarity."

“The players had real leverage. But we knew we could sit back and watch them implode.”

- NFL OWNER

According to Jenkins, Long and other coalition sources, overtures were made to Kaepernick to rejoin, but a stalemate ensued. Members say they offered to fly to a place of Kaepernick's choosing for a face-to-face meeting, but Kaepernick and Reid routinely changed the conditions of a summit, and it never materialized. Reid recalls a very different scenario: an ultimatum to attend a Nov. 7 meeting in Dallas that he couldn't attend because of his grandmother's funeral. Says Reid: "We just didn't see eye to eye on why the owners were meeting with us. We never wanted the NFL's money. It was never about that. It was about us as players using our platforms to help organizations and people. We're not experts. We wanted to get the experts involved and let the experts handle this."

A union source points out the obvious historical parallels to the civil rights movement: The idealistic and uncompromising Reid and Kaepernick faction was at odds with the Jenkins-Boldin faction, which was willing to work with, and within, the system. "It's like it was then," the source says. "The legislation wasn't perfect. You didn't get everything you wanted, but you had more than you had before."

Long was disheartened by the discord. He was a vocal supporter of Kaepernick and donated his entire 2017 salary to charity after the violent protests in Charlottesville. When he chose to leave the Patriots, whose Super Bowl fete at the White House he did not attend, and test the free agent market, his phone didn't ring -- a stark contrast to his free agency the year before, when he fielded many calls after two injury-riddled seasons. "So now you're wondering," he says. "What was it? I wanted to play. Was it because I was supportive of Kaep? You didn't know. I had to make phone calls."

As one of the only white players in professional sports taking a public and active stand in solidarity with the protesting players, the rifts were particularly painful to him. "I sort of felt like the kid watching their parents get divorced," Long says. "I think so much of this is personality-based. I honestly believe that a phone call or a meeting could have cleared all this up. But we never got there."

JENKINS AND LONG are hopeful that time and the offseason will heal the breaches. According to the agreement the coalition struck with the league in November, players are expected to make a significant contribution to match the owners. Jenkins says the funding mechanisms on the players' side are still being worked out. The same is true for control over the joint advisory board that the league and coalition formed to oversee the initiative. In its current form, with five players, five owners and two NFL-appointed members, the league owns the tiebreakers for any disputes, a point that concerned the kneelers. They see their concerns playing out already: Recently, the NFL committed funds to the United Negro College Fund, a venerable organization but hardly on the front lines of police misconduct.

"I don't think it's as fractured as it appears in the public," Jenkins says. "Obviously, it's a sensitive subject that a lot of guys are passionate about and a lot of guys sacrificed for and put themselves out there to change. It's going to be something that's hard for everybody to see eye to eye on, but at the end of the day I'm proud of everybody who gave us input to get us here. That includes Eric Reid and Mike Thomas. They played a huge role in the things we got the league to commit to. They were in those meetings up until the very end. I think everyone's hearts are in the right place."

"I think all of the details can probably be worked out," Reid says. "But the details aren't the reason I left the coalition. I left the coalition because of Malcolm."

Looming over all of this is the issue of protest. Long believes that if the owners attempt to compel the players to stop protesting, the players will dissolve the relationship. "I believe in Malcolm," Long says. "I've watched how hard this guy works, how much he cares about this. This was never supposed to be a quid pro quo. I don't think guys would accept that."

Jenkins' pragmatism produced a result -- hard cash from the owners -- that few people thought possible when Kaepernick first began his protest. But cooperation is not the same as trust, and that looms large in the coming months. The Kaepernick collusion suit will play out as other protesters, like Reid, reach free agency. Meanwhile, for all of Long's faith, as players contribute their financial share under the agreement struck by Jenkins and Boldin, it remains to be seen whether it will result in a reduction of their protests, willingly or otherwise.

"We'll see if the league will keep its word or if the players got taken," says a former player. "But I don't think they sold out. You know what they did? They bought in."

A Protest Divided

The movement started by Colin Kaepernick endures, but its supporters are more fragmented than ever. This is the inside story of how infighting splintered a group of players once unified in its pursuit of a cause bigger than themselves.

by Howard Bryant

01/26/18

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Feb. 5 State of the Black Athlete issue. Subscribe today!

Forty-niners safety Eric Reid's instincts were buzzing as if he were anticipating a screen pass. Increasingly, they were telling him to expect the worst. For weeks during the fall of 2017, tension had been brewing within the Players Coalition, a collection of NFL players committed to addressing issues of social justice. Under scrutiny from fans, owners and even the president of the United States over recent protests during the singing of the national anthem, the players found themselves fluctuating between solidarity and fracture as they struggled to unify their message and leverage their position for change.

On Nov. 29, Reid received a text from one of the leaders of the coalition, Eagles safety Malcolm Jenkins, about Jenkins' discussions with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell and the league's player liaison, Troy Vincent. At issue was how the players could partner with owners on initiatives within the African-American community. The two sides had discussed the league making a huge donation to social justice causes. Jenkins' text to the group concluded with: "If they were to agree to this, do you think you'd be more comfortable with ending the demonstrations?" Reid believed that Jenkins -- without consent of the group -- had volunteered to end their protest in exchange for a financial commitment from the NFL.

"My head was ready to explode," Reid recalls. "I was already drifting from the coalition, and this confirmed why."

To Jenkins, financial commitment from the owners was a positive step, a pathway to putting real resources toward fighting the injustice that fueled their demonstrations. But to Reid, who had been kneeling during the national anthem since the protests began in September 2016, alongside former teammate Colin Kaepernick, the deal felt like a payoff to stop kneeling -- the final betrayal in what had been a tense season. Not long after receiving Jenkins' text, feeling sold out, Reid released a statement that he was quitting the coalition.

A few days later, the NFL said it would pledge $89 million over seven years to grassroots social justice groups, to be matched by the players. Jenkins said the NFL's money did not preclude other players from protesting if they chose, but he would no longer be demonstrating during the anthem. Yet while former player Anquan Boldin, a key member of the coalition, told the New York Daily News that "I think the NFL got it right," the deal served as a breaking point for others.

Dolphins safety Michael Thomas, who had continued to kneel during the anthem, followed Reid out of the group. Chargers lineman Russell Okung called the deal a "farce."

For Reid and other defecting players, the coalition had become the NFL's hand-picked safe alternative to Kaepernick and the kneeling players; the league had lured them with promises of social commitment and big money to cover for the real purpose of sabotaging their movement and ending the protests. The coalition, meanwhile, was insulted by the idea it had sold out, and there was heavy sentiment within the coalition and the union that Kaepernick had squandered his opportunity. They also believed that his allies, while admirable in their idealism, were impractical about how to get things done. "It's unrealistic to think everyone was going to see eye to eye, but I am encouraged the coalition is alive and well," Jenkins says. "We have a ton of players that are super interested and excited to get to work to highlight the work they've already been doing."

With the season now nearly over, a group of socially committed players remains at odds -- with Kaepernick as the dividing line. Interviews over four months with multiple players, representatives and league insiders show how the cause Kaepernick started has been slowly fractured by frustrations, unreconciled resentments and missed opportunities to fight for real change -- a potentially unifying movement that fell apart for reasons that to some observers seem inevitable in retrospect.

"The players had real leverage," an NFL owner says. "But we knew we could sit back and watch them implode."

TO UNDERSTAND THE current player division, it's important to first understand how each faction dealt with Kaepernick's unemployment.

Kaepernick had every intention of playing in the NFL this season. When the 49ers told him that they would cut him if he opted into his $14.5 million contract, after he had thrown for 2,241 yards in 11 starts in 2016, he opted out a week early, in March 2017, to get a jump on the marketplace. He knew his season-long protest during the anthem -- which he began in the final preseason game of 2016 -- had created an enormous negative for coaches and owners. So he and his team of advisers, led by agent Jeff Nalley (who declined to be interviewed for this story), set a strategy for dealing with the issue: He would grant no interviews about the NFL. "If you say nothing, nothing can be used against you," Kaepernick told me during a July interview for an upcoming book.

The possibility that there would be repercussions for his protest, however, was never far from the minds of his advisers -- or the NFL Players Association. Following the Super Bowl last year, the union reached out to Kaepernick's team to inquire about formulating a collusion case in anticipation that he'd be frozen out of the league. Kaepernick's advisers declined, wanting to approach the free agent and draft periods with an open mind. As the calendar turned and quarterbacks with lesser pedigrees were signed, Kaepernick waited. Criticism mounted from members of the media, teams and even fellow players and union insiders over Kaepernick's decision to opt out of his deal instead of forcing the 49ers to release him, yet he still chose not to respond. (Kaepernick has not conducted a formal news conference or television interview in over a year.)

By summer's end, his support team looked with optimism toward the first month of the season. Certainly, his advisers reasoned, a contender with a hole under center would tap him as a veteran replacement. They reasoned incorrectly. Indianapolis had been in limbo throughout training camp with the injured Andrew Luck but then acquired Jacoby Brissett from the Patriots. The Broncos' quarterback situation was a mess, but the team decided to sign Brock Osweiler, a Browns castoff who had started in Denver previously. When Ryan Tannehill went down in Miami, the team lured Jay Cutler out of retirement with $10 million. The humiliations mounted. Still, Kaepernick said nothing.

Simmering through all this were what Kaepernick's advisers deemed a series of major slights by the union, dating to Aug. 31, 2016, when a story by Mike Freeman of Bleacher Report contained this passage: "One executive said he hasn't seen this much collective dislike among front office members regarding a player since Rae Carruth. Remember Rae Carruth? He's still in prison for the plot to murder his pregnant girlfriend."

That sentiment bothered Kaepernick, but it did not bother him nearly as much as what occurred after: silence from the NFLPA and its executive director, DeMaurice Smith.

"How could they f---ing let that pass? Nobody defended him," says one member of Kaepernick's inner circle. "You just let them compare one of your players, who had done nothing except try to help some of the most vulnerable people in this country ... you let them compare him to a f---ing murderer?" (Carruth was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and two other charges.) According to a union source, the NFLPA had a different focus at the time: "We're concerned with the legal aspects of this case, and they want us to make them feel better."

The Kaepernick team did want them to make their guy feel better. No one had risked more than Kaepernick, and no one was losing more. The least the union could do, members of Kaepernick's team thought, was provide a fierce, public shield of support.

Meanwhile, civil rights leader Al Sharpton attempted to mobilize his National Action Network to organize a boycott of the NFL on Sept. 10 -- opening Sunday -- if Kaepernick remained unsigned. But Sharpton had two problems, both of which spoke to the growing tensions among the protesters. The first was the fact that the players seemed prepared to play without a formal response to Kaepernick's situation; they had planned no gesture of solidarity via a news conference or an on-field action on behalf of Kaepernick. "How much can we be expected to do when these players are willing to sacrifice one of their own?" Sharpton said a month before the regular season began.

Sharpton's second problem was Kaepernick. According to Sharpton, Kaepernick's camp ignored his overtures during the spring and summer as fans organized spontaneous boycotts supporting the quarterback. The moment was slipping away. "We want to help," Sharpton said. "There's a feeling that people with buying power don't support him, and believe me, we can show the NFL that plenty of black people with buying power do support him. All he has to do is say the word and we'll get 10,000 people out in front of NFL headquarters or wherever he wants to go, but I don't know what his strategy is. Does he have a strategy?"

AS QUESTIONS WERE being raised about Kaepernick's silence, the NFLPA was wrestling with its own strategy for how to deal with protesting players. It supported the players' right to demonstrate (a dozen players did so on opening day in 2016), but the union believed its primary responsibility wasn't to eradicate police brutality- but to protect jobs and increase salaries -- and if sponsors distanced themselves from the league, it would shrink the financial pie for players. But the thorniest issue was that it was impossible to know if there was universal player support -- from a membership of nearly 2,000 -- for the on-field demonstrations.

Over a year after Kaepernick first took a knee, it still perplexes Smith that the union could be accused of not being supportive. Smith says he had decided the most important thing he could do after the quarterback's August 2016 protest was to maintain the right of the players to protest at work, and so he gave an interview to Dave Zirin of The Nation in which he defended that right. When the league did not move to punish Kaepernick, Smith believed he had protected his player. Combined with the NFLPA's expressed willingness to mount a collusion case, Smith believes that refutes the notion that the union was lukewarm to Kaepernick's cause.

Yet the stalemate between Kaepernick and the NFLPA deepened this season. In early September, Kaepernick's representatives flew to Washington to meet with the union's legal team, general counsel Tom DePaso and senior director of player affairs Don Davis. Both sides agreed to remain in contact and strategize as the season progressed, but now, months later, each side alleges the other never called back. Kaepernick's team says that it asked Smith to write a public statement charging the NFL with collusion but that Smith refused. According to a union source, the reason the union didn't publicly accuse the owners of collusion was that it would have immediately started a statute of limitations on a collusion action, which would have undercut the union's position.

Then came the moment that changed the season: President Donald Trump's Sept. 22 speech in Huntsville, Alabama, during which he turned his focus on the player protests. "Wouldn't you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, 'Get that son of a bitch off the field right now? Out. He's fired! Fired!'"

For the first time in a year, the players had a cause that could band them together as a union. In the week after, white and black players knelt, shot their fists into the air and locked arms. Even Dallas owner Jerry Jones took a knee before an anthem.

"[Kaepernick] did such a brave thing, such a selfless thing, that has resulted in other guys doing a selfless thing, and it reached the president of the United States," Smith says. "And it pissed off some sponsors, media and fans, but it took back the curtain, and our players got to see these people for what they truly were, and it made our union stronger. It allowed me to say the same thing to all 32 teams: All of you responded with more respect than the president gave you. The best conversations about race, inequality and social justice were occurring in a room of quote-unquote millennials where people on the outside think of you as insular, self-centered and inattentive."

But even with the momentum shifting toward the players, discord simmered. The original group of dissenters -- kneelers such as Reid, Eli Harold of the 49ers and Kenny Stills of the Dolphins -- was concerned its movement was being smothered by the president's spectacle. Were the protests about Trump or the recent violence in Charlottesville? And while everyone was patting himself on the back for taking a stand, they pointed out, Kaepernick was still unemployed.

Two weeks later, high-profile defense attorney Mark Geragos filed a formal charge of collusion on behalf of Kaepernick against the NFL. What was felt privately in his camp all spring and summer could now be said out loud: Kaepernick believed he was being blackballed by the NFL.

The next obvious step was for Kaepernick's team and the union to begin working together on their case. But according to both the NFLPA and Kaepernick's legal team, when NFLPA counsel texted Kaep-ernick requesting that he meet with Smith, Kaepernick rebuffed the idea. He told them to talk to his lawyers, who were handling the case. Kaepernick's advisers saw the response as standard. The union was insulted. The bad blood increased.

AS EARLY AS the 2017 preseason, Malcolm Jenkins had been in talks with Goodell about partnering with the NFL on criminal justice initiatives. For two seasons, he'd raised his fist in the air during the anthem -- a nod to the iconic 1968 Summer Olympics protest of John Carlos and Tommie Smith -- and did work off the field with congressional leaders, local police and community organizers. In 2016, along with Boldin, he formed the advocacy group that would become the Players Coalition, growing it to roughly 50 players over the following year and a half. (Reid joined in September 2017.) Along the way, they engaged Goodell and Vincent about ways the league and players could partner on issues important to the players. Jenkins had always wanted the movement to be player-led, with minimal input from the union.

"It showed the convictions of the players, it showed the intelligence of the players, and quite frankly, we kept the PA at bay," Jenkins says. "They didn't want us in a room talking to the league, but we were going to do it anyway. So they came along to make sure things went smoothly." The coalition first met with the owners in New York in late September. Jenkins, Reid and several other players attended. Reid described it as a "dance," in which talk of common ground persisted without substantial result. The second meeting, in Washington a few weeks later, contained even more tension, according to multiple players and union members who were there. Goodell attended with owners John Mara of the Giants, Art Rooney II of the Steelers and Robert Kraft of the Patriots. Representing the players were Smith, Washington's Josh Norman and Kirk Cousins, the Jets' Demario Davis and the Eagles' Chris Long. The players told the owners they appreciated their willingness to work together but chastised their lack of public support in the face of Trump's criticism.

Norman referenced the league's domestic violence crises and how quickly the NFL sprang into action, contrasting that to the time it was taking to address players' current concerns. Jenkins and NFLPA president Eric Winston both mentioned how much money in campaign contributions owners gave to Trump, which to them explained why they allowed him to savage the players.

Smith didn't hold back either. "You've been fine with the players being out front on this issue," he said at one point, "and you were happy with our players taking a beating from the right and being characterized as anti-cop, anti-America, anti-military, and that's bulls -- t."

At another juncture, Long recalls making a different point to the owners, which was then echoed by other players: "We haven't forgotten Kaep doesn't have a job. He deserves a job."

Over a year after Kaepernick first took a knee, it still perplexes DeMaurice Smith, pictured here talking to Jerry Jones, that the union could be accused of not being supportive. ROB CARR/GETTY IMAGES

FOR A FEW weeks between late October and early November, the players appeared unified; in group chats and phone calls, they discussed strategy for negotiating with the owners. Through Reid, Kaepernick was kept up to speed, and Kaepernick soon agreed to join the coalition.

But the coalition was fracturing along a tenuous line. Players like Reid, who primarily protested by taking a knee and who believed their protest was directly linked to Kaepernick's employment, saw themselves as taking the greatest risk. Kaepernick was out of the league, as was longtime veteran defensive back Antonio Cromartie, who had taken a knee to start 2016 and was cut after four games by the Colts. Reid himself was in a contract year. And although Jenkins maintained that all the players in the coalition could offer input on a massive group text-messaging chain, the kneelers felt as if they had nominal influence.

Reid had been wary of the coalition dating to the first New York meeting, when, as ESPN The Magazine previously reported, Bills owner Terry Pegula suggested that Boldin would be the perfect NFL spokesman on social issues, in part because it couldn't be a "white owner but needs to be someone who's black." Reid suggested Kaepernick. "If there's going to be a face to this, it needs to be Colin," Reid recalls saying. The room did not respond.

The kneelers didn't feel particularly supported by the union either. In early October, when Jerry Jones threatened to bench any Cowboys player who demonstrated, Reid called Smith, asking him what the union response would be. "You just heard a guy blatantly threaten our job security," Reid remembers saying, "and you're not going to respond?" Smith said he already had Goodell's assurances that players would not be punished for protesting, as well as the assurance of Giants owner John Mara, one of the game's most powerful brokers. "It's healthy for us to have tough discussions and even disagree at times," Smith says now. "We will be taking measures this offseason to work with agents and the league to make sure players know their rights and clubs respect the rights we all agreed are protected."

But personal animus lingered after Jones' threat. There was jousting between Kaepernick and Jenkins about leadership of the coalition. Reid says the group had agreed that there would be an inclusive leadership structure, yet he felt that Jenkins had annointed himself the leader of the coalition. Meanwhile, Jenkins says his only goal was to have players united to fight issues important to them -- he was moved to action when police killed Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, the same as Reid and Kaepernick. "We got to this moment, we're all here for the same reason," he says, "and that is we want to see change in our communities, especially black communities. The goal isn't the protest. The goal is to move beyond the protest and make some changes."

The divide grew when Geragos went public about Kaepernick not being invited by the players to the October New York meeting. According to two players in the group, Jenkins and other members of the coalition did not like Kaepernick "lawyering up."

On Oct. 28, Jenkins sent a message to the group chat that read, "Heads up guys. I removed Kap from this chat. His attorneys have been contacting me and it seems clear to me that he is not interested in working under the Coalition. I think it's important that we keep him involved in what we do and he will still be invited to meetings that we have. But in regards to our decision making and communications between members of the Coalition, I think it's important to keep these things in house in the spirit of solidarity."

“The players had real leverage. But we knew we could sit back and watch them implode.”

- NFL OWNER

According to Jenkins, Long and other coalition sources, overtures were made to Kaepernick to rejoin, but a stalemate ensued. Members say they offered to fly to a place of Kaepernick's choosing for a face-to-face meeting, but Kaepernick and Reid routinely changed the conditions of a summit, and it never materialized. Reid recalls a very different scenario: an ultimatum to attend a Nov. 7 meeting in Dallas that he couldn't attend because of his grandmother's funeral. Says Reid: "We just didn't see eye to eye on why the owners were meeting with us. We never wanted the NFL's money. It was never about that. It was about us as players using our platforms to help organizations and people. We're not experts. We wanted to get the experts involved and let the experts handle this."

A union source points out the obvious historical parallels to the civil rights movement: The idealistic and uncompromising Reid and Kaepernick faction was at odds with the Jenkins-Boldin faction, which was willing to work with, and within, the system. "It's like it was then," the source says. "The legislation wasn't perfect. You didn't get everything you wanted, but you had more than you had before."

Long was disheartened by the discord. He was a vocal supporter of Kaepernick and donated his entire 2017 salary to charity after the violent protests in Charlottesville. When he chose to leave the Patriots, whose Super Bowl fete at the White House he did not attend, and test the free agent market, his phone didn't ring -- a stark contrast to his free agency the year before, when he fielded many calls after two injury-riddled seasons. "So now you're wondering," he says. "What was it? I wanted to play. Was it because I was supportive of Kaep? You didn't know. I had to make phone calls."

As one of the only white players in professional sports taking a public and active stand in solidarity with the protesting players, the rifts were particularly painful to him. "I sort of felt like the kid watching their parents get divorced," Long says. "I think so much of this is personality-based. I honestly believe that a phone call or a meeting could have cleared all this up. But we never got there."

JENKINS AND LONG are hopeful that time and the offseason will heal the breaches. According to the agreement the coalition struck with the league in November, players are expected to make a significant contribution to match the owners. Jenkins says the funding mechanisms on the players' side are still being worked out. The same is true for control over the joint advisory board that the league and coalition formed to oversee the initiative. In its current form, with five players, five owners and two NFL-appointed members, the league owns the tiebreakers for any disputes, a point that concerned the kneelers. They see their concerns playing out already: Recently, the NFL committed funds to the United Negro College Fund, a venerable organization but hardly on the front lines of police misconduct.

"I don't think it's as fractured as it appears in the public," Jenkins says. "Obviously, it's a sensitive subject that a lot of guys are passionate about and a lot of guys sacrificed for and put themselves out there to change. It's going to be something that's hard for everybody to see eye to eye on, but at the end of the day I'm proud of everybody who gave us input to get us here. That includes Eric Reid and Mike Thomas. They played a huge role in the things we got the league to commit to. They were in those meetings up until the very end. I think everyone's hearts are in the right place."

"I think all of the details can probably be worked out," Reid says. "But the details aren't the reason I left the coalition. I left the coalition because of Malcolm."

Looming over all of this is the issue of protest. Long believes that if the owners attempt to compel the players to stop protesting, the players will dissolve the relationship. "I believe in Malcolm," Long says. "I've watched how hard this guy works, how much he cares about this. This was never supposed to be a quid pro quo. I don't think guys would accept that."

Jenkins' pragmatism produced a result -- hard cash from the owners -- that few people thought possible when Kaepernick first began his protest. But cooperation is not the same as trust, and that looms large in the coming months. The Kaepernick collusion suit will play out as other protesters, like Reid, reach free agency. Meanwhile, for all of Long's faith, as players contribute their financial share under the agreement struck by Jenkins and Boldin, it remains to be seen whether it will result in a reduction of their protests, willingly or otherwise.

"We'll see if the league will keep its word or if the players got taken," says a former player. "But I don't think they sold out. You know what they did? They bought in."