You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Mueller Report

- Thread starter QueEx

- Start date

Follow the money Follow the covfefe And follow the T.P.!

The Stunning History of William Barr’s Crusade to Bury Evidence to Protect Republican Presidents

William Barr is an old apparatchik RepubliKlan 'Fixer'. He was the guy brought in to help Papa Bushit and his minions avoid going to jail for the illegal Iran-Contra affair after the special prosecutor at-that-time Lawrence Walsh had the evidence to put them all in jail. Barr is the equivalent of the character Mr. Wolf from the movie Pulp Fiction; he's the "cleaner" brought in to deodorize Trump's putrid behavior & obstruction as much as possible

.

March 25, 2019

https://www.nationalmemo.com/bill-barrs-remarkable-history-of-scandalous-cover-up

Back in 1992, the last time Bill Barr was U.S. attorney general, iconic New York Times writer William Safire referred to him as “Coverup-General Barr” because of his role in burying evidence of then-President George H.W. Bush’s involvement in “Iraqgate” and “Iran-Contra.”

Coverup-General Barr has struck again—this time, in similar fashion, burying Mueller’s report and cherry-picking fragments of sentences from it to justify Trump’s behavior. In his letter, he notes that Robert Mueller “leaves it to the attorney general to decide whether the conduct described in the report constitutes a crime.”

As attorney general, Barr—without showing us even a single complete sentence from the Mueller report—decided there are no crimes here. Just keep moving along.

Barr’s history of doing just this sort of thing to help Republican presidents in legal crises explains why Trump brought him back in to head the Justice Department.

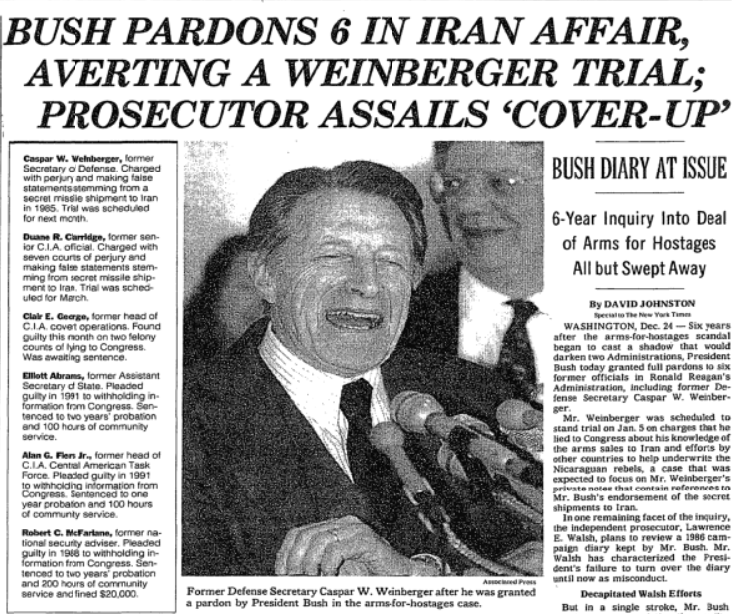

Christmas day of 1992, the New York Times featured a screaming all-caps headline across the top of its front page: Attorney General Bill Barr had covered up evidence of crimes by Reagan and Bush in the Iran-Contra scandal.

Earlier that week of Christmas, 1992, George H.W. Bush was on his way out of office. Bill Clinton had won the White House the month before, and in a few weeks would be sworn in as president.

But Bush’s biggest concern wasn’t that he’d have to leave the White House to retire back to Connecticut, Maine, or Texas (where he had homes) but, rather, that he may end up embroiled even deeper in Iran-Contra and that his colleagues may face time in a federal prison after he left office.

Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh was closing in fast on him, and Bush’s private records, subpoenaed by the independent counsel’s office, were the key to it all.

Walsh had been appointed independent counsel in 1986 to investigate the Iran-Contra activities of the Reagan administration and determine if crimes had been committed.

Was the Iran-Contra criminal conspiracy limited, as Reagan and Bush insisted (and Reagan confessed on TV), to later years in the Reagan presidency, in response to a hostage-taking in Lebanon? Or had it started in the 1980 campaign with collusion with the Iranians, as the then-president of Iran asserted? Who knew what, and when? And what was George H.W. Bush’s role in it all?

Walsh had zeroed in on documents that were in the possession of Reagan’s former defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger, who all the evidence showed was definitely in on the deal, and President Bush’s diary that could corroborate it. Elliott Abrams had already been convicted of withholding evidence from Congress, and he may have even more information, too, if it could be pried out of him before he went to prison. But Abrams was keeping mum, apparently anticipating a pardon.

Weinberger, trying to avoid jail himself, was preparing to testify that Bush knew about it and even participated, and Walsh had already, based on information he’d obtained from the investigation into Weinberger, demanded that Bush turn over his diary from the campaign. He was also again hot on the trail of Abrams.

So Bush called in his attorney general, Bill Barr, and asked his advice.

Barr, along with Bush, was already up to his eyeballs in cover-ups of shady behavior by the Reagan administration.

New York Times writer William Safire referred to him not as “Attorney General” but, instead, as “Coverup-General,” noting that in another scandal—having to do with Bush selling weapons of mass destruction to Saddam Hussein—Barr was already covering up for Bush, Weinberger, and others from the Reagan administration.

On October 19, 1992, Safire wrote of Barr’s unwillingness to appoint an independent counsel to look into Iraqgate:

“Why does the Coverup-General resist independent investigation? Because he knows where it may lead: to Dick Thornburgh, James Baker, Clayton Yeutter, Brent Scowcroft and himself [the people who organized the sale of WMD to Saddam]. He vainly hopes to be able to head it off, or at least be able to use the threat of firing to negotiate a deal.”

Now, just short of two months later, Bush was asking Barr for advice on how to avoid another very serious charge in the Iran-Contra crimes. How, he wanted to know, could they shut down Walsh’s investigation before Walsh’s lawyers got their hands on Bush’s diary?

In April of 2001, safely distant from the swirl of D.C. politics, the University of Virginia’s Miller Center was compiling oral presidential histories, and interviewed Barr about his time as AG in the Bush White House. They brought up the issue of the Weinberger pardon, which put an end to the Iran-Contra investigation, and Barr’s involvement in it.

Turns out, Barr was right in the middle of it.

“There were some people arguing just for [a pardon for] Weinberger, and I said, ‘No, in for a penny, in for a pound,’” Barr told the interviewer. “I went over and told the President I thought he should not only pardon Caspar Weinberger, but while he was at it, he should pardon about five others.”

Which is exactly what Bush did, on Christmas Eve when most Americans were with family instead of watching the news. The holiday notwithstanding, the result was explosive.

America knew that both Reagan and Bush were up to their necks in Iran-Contra, and Democrats had been talking about impeachment or worse. The independent counsel had already obtained one conviction, three guilty pleas, and two other individuals were lined up for prosecution. And Walsh was closing in fast on Bush himself.

So, when Bush shut the investigation down by pardoning not only Weinberger, but also Abrams and the others involved in the crimes, destroying Walsh’s ability to prosecute anybody, the New York Times ran the headline all the way across four of the six columns on the front page, screaming in all-caps: BUSH PARDONS 6 IN IRAN AFFAIR, ABORTING A WEINBERGER TRIAL; PROSECUTOR ASSAILS ‘COVER-UP.’

Bill Barr had struck.

The second paragraph of the Times story by David Johnston laid it out:

“Mr. Weinberger was scheduled to stand trial on Jan. 5 on charges that he lied to Congress about his knowledge of the arms sales to Iran and efforts by other countries to help underwrite the Nicaraguan rebels, a case that was expected to focus on Mr. Weinberger’s private notes that contain references to Mr. Bush’s endorsement of the secret shipments to Iran.” (emphasis added)

History shows that when a Republican president is in serious legal trouble, Bill Barr is the go-to guy.

For William Safire, it was déjà vu all over again. Four months earlier, referring to Iraqgate (Bush’s selling WMDs to Iraq), Safire opened his article, titled “Justice [Department] Corrupts Justice,” by writing:

“U.S. Attorney General William Barr, in rejecting the House Judiciary Committee’s call for a prosecutor not beholden to the Bush Administration to investigate the crimes of Iraqgate, has taken personal charge of the cover-up.”

Safire accused Barr of not only rigging the cover-up, but of being one of the criminals who could be prosecuted.

“Mr. Barr,” wrote Safire in August of 1992, “…could face prosecution if it turns out that high Bush officials knew about Saddam Hussein’s perversion of our Agriculture export guarantees to finance his war machine.”

He added, “They [Barr and colleagues] have a keen personal and political interest in seeing to it that the Department of Justice stays in safe, controllable Republican hands.”

Earlier in Bush’s administration, Barr had succeeded in blocking the appointment of an investigator or independent counsel to look into Iraqgate, as Safire repeatedly documented in the Times. In December, Barr helped Bush block indictments from another independent counsel, Lawrence Walsh, and eliminated any risk that Reagan or George H.W. Bush would be held to account for Iran-Contra.

Walsh, wrote Johnston for the Times on Christmas Eve, “plans to review a 1986 campaign diary kept by Mr. Bush.” The diary would be the smoking gun that would nail Bush to the scandal.

“But,” noted the Times, “in a single stroke, Mr. Bush [at Barr’s suggestion] swept away one conviction, three guilty pleas and two pending cases, virtually decapitating what was left of Mr. Walsh’s effort, which began in 1986.”

And Walsh didn’t take it lying down.

The Times report noted that, “Mr. Walsh bitterly condemned the President’s action, charging that ‘the Iran-contra cover-up, which has continued for more than six years, has now been completed.’”

Independent Counsel Walsh added that the diary and notes he wanted to enter into a public trial of Weinberger represented, “evidence of a conspiracy among the highest ranking Reagan Administration officials to lie to Congress and the American public.”

The phrase “highest ranking” officials included Reagan and Bush.

Walsh had been fighting to get those documents ever since 1986, when he was appointed and Reagan still had two years left in office. Bush’s and Weinberger’s refusal to turn them over, Johnston noted in the Times, could have, in Walsh’s words, “forestalled impeachment proceedings against President Reagan” through a pattern of “deception and obstruction.”

Barr successfully covered up the involvement of two Republican presidents—Reagan and Bush—in two separate and perhaps impeachable “high crimes.” And months later, newly sworn-in President Clinton and the new Congress decided to put it all behind them and not pursue the matters any further.

Now, by cherry-picking Mueller’s report and handing Trump the talking points he needed, Barr has done it again.

The question this time is whether Congress will be as compliant as they were in 1993 and simply let it all go.

Both Trump and senior Republican leadership are already calling for a repeat of ’93; what remains to be seen is if the press and Democratic leadership will go along like they did back then.

Last edited:

HAPPENING NOW: Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal makes remarks following release of redacted Mueller report. https://abcn.ws/2Xh3JLI

A bit premature there, Spanky.

Mueller's report outlines obstruction evidence, Russian election interference

The Justice Department on Thursday released Special Counsel Robert Mueller's report on the Trump campaign's conduct surrounding Russian election interference in 2016.

The report, which determined that Russia interfered in the election in a "sweeping and systematic fashion," says President Trump and his campaign did not criminally conspire with the Russian efforts, but it did not determine whether any conduct constituted obstruction of justice.

The report says evidence obtained "about the president's actions and intent presents difficult issues that prevent us from conclusively determining that no criminal conduct occurred." Citing 10 instances of suspicious behavior, Mueller said Trump tried to "influence" the investigation but was "mostly unsuccessful" because aides refused to "carry out orders."

Source: Justice Department

.

The Justice Department on Thursday released Special Counsel Robert Mueller's report on the Trump campaign's conduct surrounding Russian election interference in 2016.

The report, which determined that Russia interfered in the election in a "sweeping and systematic fashion," says President Trump and his campaign did not criminally conspire with the Russian efforts, but it did not determine whether any conduct constituted obstruction of justice.

The report says evidence obtained "about the president's actions and intent presents difficult issues that prevent us from conclusively determining that no criminal conduct occurred." Citing 10 instances of suspicious behavior, Mueller said Trump tried to "influence" the investigation but was "mostly unsuccessful" because aides refused to "carry out orders."

Source: Justice Department

.

Attorney General Bill Barr released a redacted version of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's report about Russian interference and the Trump campaign to Congress and the American people April 18, 2019. Read the Report here:

https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/article/2019/apr/18/read-redacted-mueller-report/

By PolitiFact Staff on Thursday, April 18th, 2019.

Unanswered Questions in the Mueller Report Point to a Sprawling Russian Spy Game

https://theintercept.com/2019/04/28/mueller-report-trump-russia-questions/

Throughout Robert Mueller’s two-year investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election, Paul Manafort had a target on his back. The former Trump campaign chair’s longstanding ties to powerful figures in Ukraine and Russia triggered intense scrutiny from Mueller, as he and his fellow prosecutors sought to determine whether President Donald Trump or the people around him conspired with Moscow to win the presidency.

Mueller saw Manafort as a central figure in his investigation and went after him repeatedly and aggressively; as a result, Manafort ultimately faced a variety of charges in federal courts in Virginia and Washington, D.C. Mueller offered Manafort a plea deal in exchange for Manafort telling the special counsel what he knew about Trump and Russia. But Mueller eventually grew angry because Manafort continued to lie to him. A federal judge determined that Manafort had violated his plea agreement, in part by lying about his communications with a longtime Manafort employee who the FBI assessed had ties to Russian intelligence. Manafort is now in prison.

In the end, Mueller’s investigators could not find evidence that Manafort coordinated his actions with the sophisticated Russian cybercampaign to help Trump win. But the report makes clear that there were many instances in which Mueller wasn’t able to get to the bottom of things and often couldn’t determine the whole story behind the Trump-Russia contacts.

In fact, the report documents a series of strange and still unexplained contacts between the Trump crowd and Russia. It is filled with unresolved mysteries.

One reason Mueller wasn’t able to answer many of the questions surrounding those contacts was that he had to navigate a blizzard of lies. “The investigation established that several individuals affiliated with the Trump campaign lied to [the Mueller team], and to Congress, about their interactions with Russian-affiliated individuals and related matters,” the report states. “Those lies materially impaired the investigation of Russian election interference.”

Some in the Trump circle, including Manafort and former national security adviser Michael Flynn, faced criminal charges for their falsehoods. In other cases, Mueller was blocked by the refusal of key figures to talk, while other potential witnesses were not credible or were out of reach overseas.

When it came to the infamous June 9, 2016 meeting at Trump Tower in New York between key members of the Trump circle and a Russian lawyer, for example, Mueller was unable to question the two most important participants. The president’s oldest son, Donald Trump Jr., refused to be interviewed by Mueller, while Natalia Veselnitskaya, the Russian lawyer, was in Russia and couldn’t be questioned. The report says that Mueller considered bringing campaign finance charges against some in the Trump circle who participated in the meeting but decided not to.

And what are we to make of the brief but mysterious interactions during the campaign between George Papadopoulos, a young Trump foreign policy adviser, and Sergei Millian, an American who was born in Belarus? Among other contacts with Papadopoulos, Millian sent him a Facebook message in August 2016 promising to “share with you a disruptive technology that might be instrumental in your political work for the campaign.”

The report notes that Mueller’s team was “not fully able to explore the contact because the individual at issue, Sergei Millian, remained out of the country since the inception of our investigation and declined to meet with members of [Mueller’s team] despite our repeated efforts to obtain an interview.” (This isn’t the first time Millian’s name has surfaced in connection with the Trump-Russia case. During the campaign, Millian reportedly told an associate that Trump had longstanding ties to Russia and that the Russians were passing on damaging information about Hillary Clinton. Millian’s assertions ended up as secondhand information in the Steele dossier, an opposition research report on possible links between the Trump campaign and Russia compiled by a former British intelligence officer in 2016.)

In yet another instance, Mueller investigated whether anyone around Trump coordinated with WikiLeaks to release stolen emails from Clinton campaign chair John Podesta on October 7, 2016, about an hour after the Washington Post reported on an “Access Hollywood” audiotape of Trump using crude language about women. The release of the emails seemed designed to distract attention from the “Access Hollywood” tape, which had the makings of a major political scandal.

Jerome Corsi, a conservative author with close ties to Trump ally Roger Stone, told Mueller that he believed his actions prompted the quick WikiLeaks release, but Mueller’s report says investigators couldn’t corroborate Corsi’s story. The report doesn’t offer any other explanation for the release of the Podesta emails on what turned out to be one of the most important days of the 2016 campaign.

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s redacted report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. These pages refer to former campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

Photo: Jon Elswick/AP

Mueller’s frustration with Manafort’s lies reflects a major theme in the report’s account of the contacts between people around Trump and figures with ties to Russia. Although Mueller’s investigation “identified numerous links between individuals with ties to the Russian government and individuals associated with the Trump campaign, the evidence was not sufficient to support criminal charges,” the report states. It adds that “the evidence was not sufficient to charge that any member of the Trump campaign conspired with representatives of the Russian government to interfere in the 2016 election.”

It’s important to remember that as special counsel, Mueller was trying to answer very narrow questions about whether contacts between the Trump circle and Russia were directly related to the Russian cybercampaign against the Democratic Party, and whether those actions violated federal law.

But that narrow scope may have obscured the possibility that the Russians were seeking to gain influence in the United States in many different ways at the same time. The reality is that every great power, including the United States and Russia, conducts many different intelligence operations simultaneously against its adversaries. The cyberoffensive against the Democratic Party, launched by the GRU, Russian military intelligence, could have been going on separately from a more diffuse Russian effort to gather intelligence and probe for influence in Washington.

The report makes clear that Manafort remained a frustrating enigma to Mueller. It’s not hard to read between the lines and glean that Mueller, the straight-arrow prosecutor, former FBI director, and former Marine, was revulsed by the international political consultant’s corrupt behavior and found it difficult to comprehend his willingness to work for Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs. In this regard, Manafort was a sort of object of fascination for Mueller.

Mueller had good reason to focus on Manafort. Before he joined the Trump campaign, Manafort made millions working for Oleg Deripaska, a Russian oligarch with extensive international aluminum and power holdings and close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Rick Gates, Manafort’s former deputy, who pleaded guilty to conspiracy and lying to the FBI and agreed to cooperate with the special counsel’s office, explained that Deripaska used Manafort to install friendly political officials in countries where Deripaska had business interests.

Manafort’s work for Deripaska began in about 2005 and ultimately led him to Rinat Akhmetov, a Ukrainian oligarch who brought Manafort in as a political consultant in Ukraine for the pro-Russian Party of Regions. Manafort helped Viktor Yanukovych, the Party of Regions candidate, win the presidency in 2010. Manafort became a close adviser to Yanukovych until he was forced to flee to Russia in 2014 in the wake of the Maidan Revolution in Kiev that ousted his government.

With Yanukovych’s ouster, Manafort lost his meal ticket in Ukraine. By then, his relations with Deripaska had also turned bitter. Deripaska had invested in a fund created by Manafort that had failed, and he wanted his money back.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, shakes hands with Russian metals magnate Oleg Deripaska while visiting the RusVinyl plant in Russia’s Nizhny Novgorod region on Sept. 19, 2014.

Photo: RIA-Novosti/Mikhail Klimentyev/Presidential Press Service via AP

By the time Manafort joined the Trump team, he was eager to make peace with Deripaska. The Mueller report says that right after joining the campaign, Manafort asked Gates, who had accompanied him into Trump’s orbit, to prepare memos for Deripaska, Akhmetov, and two other Ukrainian oligarchs about Manafort’s new post with Trump and his willingness to work on Ukrainian politics in the future.

During this period, Konstantin Kilimnik, a Russian national and longtime Manafort employee, served as an intermediary between Manafort, Deripaska, and Yanukovych. The FBI has concluded that Kilimnik has ties to Russian intelligence; indeed, Kilimnik’s connection to Deripaska was through a Deripaska deputy who had previously served in the defense attaché’s office in the Russian embassy in Washington. While it is not known whether the Deripaska deputy, Victor Boyarkin, has an intelligence background, a position in an embassy defense attaché’s office is commonly used as cover for intelligence officers.

Manafort met with Kilimnik twice in the United States during the campaign. In one meeting, Manafort discussed with Kilimnik the political situation in the battleground states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota, according to the report.

Manafort also arranged for Gates to send Kilimnik updates on the Trump campaign, including internal polling data, which he asked Kilimnik to pass on to Deripaska. Manafort also communicated with Kilimnik about pro-Russian peace plans for Ukraine at least four times during and after the campaign.

Those frequent communications between Manafort and prominent people from Ukraine and Russia in the midst of the campaign certainly raised Mueller’s suspicions. But Mueller ultimately couldn’t find evidence of a connection between Manafort’s decision to give polling data to Kilimnik and the Russian cyberoffensive in the 2016 election. The special counsel and his team “could not reliably determine Manafort’s purpose in sharing internal polling data with Kilimnik during the campaign period,” the report notes, adding that “because of questions about Manafort’s credibility and our limited ability to gather evidence on what happened to the polling data after it was sent to Kilimnik, [Mueller’s team] could not assess what Kilimnik [or others with whom he may have shared it] did with it.”

Mueller’s investigators did not find evidence that Manafort passed along information about the Ukrainian peace plan he discussed with Kilimnik to Trump or anyone else in the campaign, or, later, to members of the Trump administration. But Mueller also notes that “while Manafort denied that he spoke to members of the Trump campaign or the new Administration about the peace plan, he lied to the [special counsel’s] office and the grand jury about the peace plan and his meetings with Kilmnik, and his unreliability on this subject was among the reasons that [the judge in his case] found that he breached his cooperation agreement.”

While the evidence Mueller gathered about Manafort may not have been sufficient to bring criminal charges, it does fit the pattern of information that might typically emerge in a counterintelligence investigation, which is very different from a criminal inquiry.

The Mueller report documents Manafort’s deep connections with Russians and Ukrainians, and shows that he shared internal campaign data with them in the hopes of winning their favor and “monetizing” his work with Trump. But the report also suggests that as Trump’s campaign chair, Manafort opened a secret backchannel with Russia for his own selfish reasons that had nothing to do with Russia’s efforts to help Trump win the election.

In one conversation with Mueller’s team, Manafort may have given the special counsel a candid answer about what was going on in his case: He made it clear that while Deripaska may not have played any role in the GRU’s cybercampaign, the oligarch still saw Manafort as a valuable long-term asset.

If Trump won, “Deripaska would want to use Manafort to advance whatever interests Deripaska had in the United States and elsewhere,” Manafort told Mueller. And Deripaska, remember, was very close to Putin.

In court documents, the Justice Department painted a similar picture of Maria Butina, the young Russian woman who has pleaded guilty to conspiring to act as an agent of the Russian Federation. (Butina was sentenced on Friday to 18 months in prison. After she completes her sentence, she will be deported.)

Butina was “not a spy in the traditional sense,” the Justice Department now says. Yet she was still part of a “deliberate intelligence operation by the Russian Federation,” according to an affidavit from a former high-level FBI counterintelligence official. She was in the United States to “spot and assess” Americans who might be susceptible to recruitment as foreign intelligence assets. In addition, she sought to establish a backchannel of communication to bypass formal diplomatic channels between Moscow and Washington.

Manafort and Butina may have been on two sides of a complex new kind of spy game that few outsiders understand.

https://theintercept.com/2019/04/28/mueller-report-trump-russia-questions/

Throughout Robert Mueller’s two-year investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election, Paul Manafort had a target on his back. The former Trump campaign chair’s longstanding ties to powerful figures in Ukraine and Russia triggered intense scrutiny from Mueller, as he and his fellow prosecutors sought to determine whether President Donald Trump or the people around him conspired with Moscow to win the presidency.

Mueller saw Manafort as a central figure in his investigation and went after him repeatedly and aggressively; as a result, Manafort ultimately faced a variety of charges in federal courts in Virginia and Washington, D.C. Mueller offered Manafort a plea deal in exchange for Manafort telling the special counsel what he knew about Trump and Russia. But Mueller eventually grew angry because Manafort continued to lie to him. A federal judge determined that Manafort had violated his plea agreement, in part by lying about his communications with a longtime Manafort employee who the FBI assessed had ties to Russian intelligence. Manafort is now in prison.

In the end, Mueller’s investigators could not find evidence that Manafort coordinated his actions with the sophisticated Russian cybercampaign to help Trump win. But the report makes clear that there were many instances in which Mueller wasn’t able to get to the bottom of things and often couldn’t determine the whole story behind the Trump-Russia contacts.

In fact, the report documents a series of strange and still unexplained contacts between the Trump crowd and Russia. It is filled with unresolved mysteries.

One reason Mueller wasn’t able to answer many of the questions surrounding those contacts was that he had to navigate a blizzard of lies. “The investigation established that several individuals affiliated with the Trump campaign lied to [the Mueller team], and to Congress, about their interactions with Russian-affiliated individuals and related matters,” the report states. “Those lies materially impaired the investigation of Russian election interference.”

Some in the Trump circle, including Manafort and former national security adviser Michael Flynn, faced criminal charges for their falsehoods. In other cases, Mueller was blocked by the refusal of key figures to talk, while other potential witnesses were not credible or were out of reach overseas.

When it came to the infamous June 9, 2016 meeting at Trump Tower in New York between key members of the Trump circle and a Russian lawyer, for example, Mueller was unable to question the two most important participants. The president’s oldest son, Donald Trump Jr., refused to be interviewed by Mueller, while Natalia Veselnitskaya, the Russian lawyer, was in Russia and couldn’t be questioned. The report says that Mueller considered bringing campaign finance charges against some in the Trump circle who participated in the meeting but decided not to.

And what are we to make of the brief but mysterious interactions during the campaign between George Papadopoulos, a young Trump foreign policy adviser, and Sergei Millian, an American who was born in Belarus? Among other contacts with Papadopoulos, Millian sent him a Facebook message in August 2016 promising to “share with you a disruptive technology that might be instrumental in your political work for the campaign.”

The report notes that Mueller’s team was “not fully able to explore the contact because the individual at issue, Sergei Millian, remained out of the country since the inception of our investigation and declined to meet with members of [Mueller’s team] despite our repeated efforts to obtain an interview.” (This isn’t the first time Millian’s name has surfaced in connection with the Trump-Russia case. During the campaign, Millian reportedly told an associate that Trump had longstanding ties to Russia and that the Russians were passing on damaging information about Hillary Clinton. Millian’s assertions ended up as secondhand information in the Steele dossier, an opposition research report on possible links between the Trump campaign and Russia compiled by a former British intelligence officer in 2016.)

In yet another instance, Mueller investigated whether anyone around Trump coordinated with WikiLeaks to release stolen emails from Clinton campaign chair John Podesta on October 7, 2016, about an hour after the Washington Post reported on an “Access Hollywood” audiotape of Trump using crude language about women. The release of the emails seemed designed to distract attention from the “Access Hollywood” tape, which had the makings of a major political scandal.

Jerome Corsi, a conservative author with close ties to Trump ally Roger Stone, told Mueller that he believed his actions prompted the quick WikiLeaks release, but Mueller’s report says investigators couldn’t corroborate Corsi’s story. The report doesn’t offer any other explanation for the release of the Podesta emails on what turned out to be one of the most important days of the 2016 campaign.

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s redacted report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. These pages refer to former campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

Photo: Jon Elswick/AP

Mueller’s frustration with Manafort’s lies reflects a major theme in the report’s account of the contacts between people around Trump and figures with ties to Russia. Although Mueller’s investigation “identified numerous links between individuals with ties to the Russian government and individuals associated with the Trump campaign, the evidence was not sufficient to support criminal charges,” the report states. It adds that “the evidence was not sufficient to charge that any member of the Trump campaign conspired with representatives of the Russian government to interfere in the 2016 election.”

It’s important to remember that as special counsel, Mueller was trying to answer very narrow questions about whether contacts between the Trump circle and Russia were directly related to the Russian cybercampaign against the Democratic Party, and whether those actions violated federal law.

But that narrow scope may have obscured the possibility that the Russians were seeking to gain influence in the United States in many different ways at the same time. The reality is that every great power, including the United States and Russia, conducts many different intelligence operations simultaneously against its adversaries. The cyberoffensive against the Democratic Party, launched by the GRU, Russian military intelligence, could have been going on separately from a more diffuse Russian effort to gather intelligence and probe for influence in Washington.

The report makes clear that Manafort remained a frustrating enigma to Mueller. It’s not hard to read between the lines and glean that Mueller, the straight-arrow prosecutor, former FBI director, and former Marine, was revulsed by the international political consultant’s corrupt behavior and found it difficult to comprehend his willingness to work for Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs. In this regard, Manafort was a sort of object of fascination for Mueller.

Mueller had good reason to focus on Manafort. Before he joined the Trump campaign, Manafort made millions working for Oleg Deripaska, a Russian oligarch with extensive international aluminum and power holdings and close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Rick Gates, Manafort’s former deputy, who pleaded guilty to conspiracy and lying to the FBI and agreed to cooperate with the special counsel’s office, explained that Deripaska used Manafort to install friendly political officials in countries where Deripaska had business interests.

Manafort’s work for Deripaska began in about 2005 and ultimately led him to Rinat Akhmetov, a Ukrainian oligarch who brought Manafort in as a political consultant in Ukraine for the pro-Russian Party of Regions. Manafort helped Viktor Yanukovych, the Party of Regions candidate, win the presidency in 2010. Manafort became a close adviser to Yanukovych until he was forced to flee to Russia in 2014 in the wake of the Maidan Revolution in Kiev that ousted his government.

With Yanukovych’s ouster, Manafort lost his meal ticket in Ukraine. By then, his relations with Deripaska had also turned bitter. Deripaska had invested in a fund created by Manafort that had failed, and he wanted his money back.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, shakes hands with Russian metals magnate Oleg Deripaska while visiting the RusVinyl plant in Russia’s Nizhny Novgorod region on Sept. 19, 2014.

Photo: RIA-Novosti/Mikhail Klimentyev/Presidential Press Service via AP

By the time Manafort joined the Trump team, he was eager to make peace with Deripaska. The Mueller report says that right after joining the campaign, Manafort asked Gates, who had accompanied him into Trump’s orbit, to prepare memos for Deripaska, Akhmetov, and two other Ukrainian oligarchs about Manafort’s new post with Trump and his willingness to work on Ukrainian politics in the future.

During this period, Konstantin Kilimnik, a Russian national and longtime Manafort employee, served as an intermediary between Manafort, Deripaska, and Yanukovych. The FBI has concluded that Kilimnik has ties to Russian intelligence; indeed, Kilimnik’s connection to Deripaska was through a Deripaska deputy who had previously served in the defense attaché’s office in the Russian embassy in Washington. While it is not known whether the Deripaska deputy, Victor Boyarkin, has an intelligence background, a position in an embassy defense attaché’s office is commonly used as cover for intelligence officers.

Manafort met with Kilimnik twice in the United States during the campaign. In one meeting, Manafort discussed with Kilimnik the political situation in the battleground states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota, according to the report.

Manafort also arranged for Gates to send Kilimnik updates on the Trump campaign, including internal polling data, which he asked Kilimnik to pass on to Deripaska. Manafort also communicated with Kilimnik about pro-Russian peace plans for Ukraine at least four times during and after the campaign.

Those frequent communications between Manafort and prominent people from Ukraine and Russia in the midst of the campaign certainly raised Mueller’s suspicions. But Mueller ultimately couldn’t find evidence of a connection between Manafort’s decision to give polling data to Kilimnik and the Russian cyberoffensive in the 2016 election. The special counsel and his team “could not reliably determine Manafort’s purpose in sharing internal polling data with Kilimnik during the campaign period,” the report notes, adding that “because of questions about Manafort’s credibility and our limited ability to gather evidence on what happened to the polling data after it was sent to Kilimnik, [Mueller’s team] could not assess what Kilimnik [or others with whom he may have shared it] did with it.”

Mueller’s investigators did not find evidence that Manafort passed along information about the Ukrainian peace plan he discussed with Kilimnik to Trump or anyone else in the campaign, or, later, to members of the Trump administration. But Mueller also notes that “while Manafort denied that he spoke to members of the Trump campaign or the new Administration about the peace plan, he lied to the [special counsel’s] office and the grand jury about the peace plan and his meetings with Kilmnik, and his unreliability on this subject was among the reasons that [the judge in his case] found that he breached his cooperation agreement.”

While the evidence Mueller gathered about Manafort may not have been sufficient to bring criminal charges, it does fit the pattern of information that might typically emerge in a counterintelligence investigation, which is very different from a criminal inquiry.

The Mueller report documents Manafort’s deep connections with Russians and Ukrainians, and shows that he shared internal campaign data with them in the hopes of winning their favor and “monetizing” his work with Trump. But the report also suggests that as Trump’s campaign chair, Manafort opened a secret backchannel with Russia for his own selfish reasons that had nothing to do with Russia’s efforts to help Trump win the election.

In one conversation with Mueller’s team, Manafort may have given the special counsel a candid answer about what was going on in his case: He made it clear that while Deripaska may not have played any role in the GRU’s cybercampaign, the oligarch still saw Manafort as a valuable long-term asset.

If Trump won, “Deripaska would want to use Manafort to advance whatever interests Deripaska had in the United States and elsewhere,” Manafort told Mueller. And Deripaska, remember, was very close to Putin.

In court documents, the Justice Department painted a similar picture of Maria Butina, the young Russian woman who has pleaded guilty to conspiring to act as an agent of the Russian Federation. (Butina was sentenced on Friday to 18 months in prison. After she completes her sentence, she will be deported.)

Butina was “not a spy in the traditional sense,” the Justice Department now says. Yet she was still part of a “deliberate intelligence operation by the Russian Federation,” according to an affidavit from a former high-level FBI counterintelligence official. She was in the United States to “spot and assess” Americans who might be susceptible to recruitment as foreign intelligence assets. In addition, she sought to establish a backchannel of communication to bypass formal diplomatic channels between Moscow and Washington.

Manafort and Butina may have been on two sides of a complex new kind of spy game that few outsiders understand.

Mueller:

Barr’s letter did not capture ‘context’ of Trump probe

Special counsel Robert S. Mueller III submitted his investigation to the Justice Department in March.

(Kevin Lamarque/Reuters)

Washington Post

By Devlin Barrett and

Matt Zapotosky

April 30 at 7:16 PM

Special counsel Robert S. Mueller III wrote a letter in late March complaining to Attorney General William P. Barr that [his] four-page memo to Congress describing the principal conclusions of the investigation into President Trump “did not fully capture the context, nature, and substance” of Mueller’s work, according to a copy of the letter reviewed Tuesday by The Washington Post.

Days after Barr’s announcement, Mueller wrote a previously unknown private letter to the Justice Department, which revealed a degree of dissatisfaction with the public discussion of Mueller’s work that shocked senior Justice Department officials, according to people familiar with the discussions.

The letter made a key request:

Justice Department officials said Tuesday they were taken aback by the tone of Mueller’s letter, and it came as a surprise to them that he had such concerns. Until they received the letter, they believed Mueller was in agreement with them on the process of reviewing the report and redacting certain types of information, a process that took several weeks. Barr has testified to Congress previously that Mueller declined the opportunity to review his four-page letter to lawmakers that distilled the essence of the special counsel’s findings.

In his letter, Mueller wrote that the redaction process “need not delay release of the enclosed materials. Release at this time would alleviate the misunderstandings that have arisen and would answer congressional and public questions about the nature and outcome of our investigation.”

Barr is scheduled to appear Wednesday morning before the Senate Judiciary Committee — a much-anticipated public confrontation between the nation’s top law enforcement official and Democratic lawmakers, where he is likely to be questioned at length about his interactions with Mueller.

A day after the letter was sent, Barr and Mueller spoke by phone for about 15 minutes, according to law enforcement officials.

In that call, Mueller said he was concerned that news coverage of the obstruction investigation was misguided and creating public misunderstandings about the office’s work, according to Justice Department officials.

When Barr pressed him whether he thought Barr’s letter was inaccurate, Mueller said he did not, but felt that the media coverage of the letter was misinterpreting the investigation, officials said.

In their call, Barr also took issue with Mueller calling his letter a “summary,” saying he had never meant his letter to summarize the voluminous report, but instead provide an account of the top conclusions, officials said.

Justice Department officials said in some ways, the phone conversation was more cordial than the letter that preceded it, but they did express some differences of opinion about how to proceed.

Barr said he did not want to put out pieces of the report, but rather issue it all at once with redactions, and didn’t want to change course now, according to officials.

Throughout the conversation, Mueller’s main worry was that the public was not getting an accurate understanding of the obstruction investigation, officials said.

“After the Attorney General received Special Counsel Mueller’s letter, he called him to discuss it,” a Justice Department spokeswoman said Tuesday. “In a cordial and professional conversation, the Special Counsel emphasized that nothing in the Attorney General’s March 24 letter was inaccurate or misleading. But, he expressed frustration over the lack of context and the resulting media coverage regarding the Special Counsel’s obstruction analysis. They then discussed whether additional context from the report would be helpful and could be quickly released.

“However, the Attorney General ultimately determined that it would not be productive to release the report in piecemeal fashion,” the spokeswoman’s statement continues. “The Attorney General and the Special Counsel agreed to get the full report out with necessary redactions as expeditiously as possible. The next day, the Attorney General sent a letter to Congress reiterating that his March 24 letter was not intended to be a summary of the report, but instead only stated the Special Counsel’s principal conclusions, and volunteered to testify before both Senate and House Judiciary Committees on May 1 and 2.”

Some senior Justice Department officials were frustrated by Mueller’s complaints, because they had expected that the report would reach them with proposed redactions the first time they got it, but it did not. Even when Mueller sent along his suggested redactions, those covered only a few areas of protected information, and the documents required further review, these people said.

Wednesday’s hearing will be the first time lawmakers will get to question Barr since the Mueller report was released on April 18, and he is expected to face a raft of tough questions from Democrats about his public announcement of the findings, his private interactions with Mueller, and his views about President Trump’s conduct.

Republicans on the committee are expected to question Barr about an assertion he made earlier this month that government officials had engaged in “spying” on the Trump campaign — a comment that was seized on by the president’s supporters as evidence the investigation into the president was biased.

Barr is also scheduled to testify Thursday before a House committee, but that hearing could be canceled or postponed amid a dispute about whether committee staff lawyers will question the attorney general.

Democrats have accused Barr of downplaying the seriousness of the evidence against the president.

In the report, Mueller described ten significant episodes of possible obstruction of justice, but said that due to long-standing Justice Department policy that says a sitting president cannot be indicted, and because of Justice Department practice regarding fairness toward those under investigation, his team did not reach a conclusion about whether the president had committed a crime.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/worl...82d3f3d96d5_story.html?utm_term=.555b90f3e35a

.

Barr’s letter did not capture ‘context’ of Trump probe

Special counsel Robert S. Mueller III submitted his investigation to the Justice Department in March.

(Kevin Lamarque/Reuters)

Washington Post

By Devlin Barrett and

Matt Zapotosky

April 30 at 7:16 PM

Special counsel Robert S. Mueller III wrote a letter in late March complaining to Attorney General William P. Barr that [his] four-page memo to Congress describing the principal conclusions of the investigation into President Trump “did not fully capture the context, nature, and substance” of Mueller’s work, according to a copy of the letter reviewed Tuesday by The Washington Post.

At the time the letter was sent on March 27, Barr had announced that Mueller had not found a conspiracy between the Trump campaign and Russian officials seeking to interfere in the 2016 presidential election. Barr also said Mueller had not reached a conclusion about whether Trump had tried to obstruct justice, but Barr reviewed the evidence and found it insufficient to support such a charge.

Days after Barr’s announcement, Mueller wrote a previously unknown private letter to the Justice Department, which revealed a degree of dissatisfaction with the public discussion of Mueller’s work that shocked senior Justice Department officials, according to people familiar with the discussions.

“The summary letter the Department sent to Congress and released to the public late in the afternoon of March 24 did not fully capture the context, nature, and substance of this office’s work and conclusions,” Mueller wrote. “There is now public confusion about critical aspects of the results of our investigation. This threatens to undermine a central purpose for which the Department appointed the Special Counsel: to assure full public confidence in the outcome of the investigations.”

The letter made a key request:

that Barr release the 448-page report’s introductions and executive summaries, and made some initial suggested redactions for doing so, according to Justice Department officials.

Justice Department officials said Tuesday they were taken aback by the tone of Mueller’s letter, and it came as a surprise to them that he had such concerns. Until they received the letter, they believed Mueller was in agreement with them on the process of reviewing the report and redacting certain types of information, a process that took several weeks. Barr has testified to Congress previously that Mueller declined the opportunity to review his four-page letter to lawmakers that distilled the essence of the special counsel’s findings.

In his letter, Mueller wrote that the redaction process “need not delay release of the enclosed materials. Release at this time would alleviate the misunderstandings that have arisen and would answer congressional and public questions about the nature and outcome of our investigation.”

Barr is scheduled to appear Wednesday morning before the Senate Judiciary Committee — a much-anticipated public confrontation between the nation’s top law enforcement official and Democratic lawmakers, where he is likely to be questioned at length about his interactions with Mueller.

A day after the letter was sent, Barr and Mueller spoke by phone for about 15 minutes, according to law enforcement officials.

In that call, Mueller said he was concerned that news coverage of the obstruction investigation was misguided and creating public misunderstandings about the office’s work, according to Justice Department officials.

When Barr pressed him whether he thought Barr’s letter was inaccurate, Mueller said he did not, but felt that the media coverage of the letter was misinterpreting the investigation, officials said.

In their call, Barr also took issue with Mueller calling his letter a “summary,” saying he had never meant his letter to summarize the voluminous report, but instead provide an account of the top conclusions, officials said.

Justice Department officials said in some ways, the phone conversation was more cordial than the letter that preceded it, but they did express some differences of opinion about how to proceed.

Barr said he did not want to put out pieces of the report, but rather issue it all at once with redactions, and didn’t want to change course now, according to officials.

Throughout the conversation, Mueller’s main worry was that the public was not getting an accurate understanding of the obstruction investigation, officials said.

“After the Attorney General received Special Counsel Mueller’s letter, he called him to discuss it,” a Justice Department spokeswoman said Tuesday. “In a cordial and professional conversation, the Special Counsel emphasized that nothing in the Attorney General’s March 24 letter was inaccurate or misleading. But, he expressed frustration over the lack of context and the resulting media coverage regarding the Special Counsel’s obstruction analysis. They then discussed whether additional context from the report would be helpful and could be quickly released.

“However, the Attorney General ultimately determined that it would not be productive to release the report in piecemeal fashion,” the spokeswoman’s statement continues. “The Attorney General and the Special Counsel agreed to get the full report out with necessary redactions as expeditiously as possible. The next day, the Attorney General sent a letter to Congress reiterating that his March 24 letter was not intended to be a summary of the report, but instead only stated the Special Counsel’s principal conclusions, and volunteered to testify before both Senate and House Judiciary Committees on May 1 and 2.”

Some senior Justice Department officials were frustrated by Mueller’s complaints, because they had expected that the report would reach them with proposed redactions the first time they got it, but it did not. Even when Mueller sent along his suggested redactions, those covered only a few areas of protected information, and the documents required further review, these people said.

Wednesday’s hearing will be the first time lawmakers will get to question Barr since the Mueller report was released on April 18, and he is expected to face a raft of tough questions from Democrats about his public announcement of the findings, his private interactions with Mueller, and his views about President Trump’s conduct.

Republicans on the committee are expected to question Barr about an assertion he made earlier this month that government officials had engaged in “spying” on the Trump campaign — a comment that was seized on by the president’s supporters as evidence the investigation into the president was biased.

Barr is also scheduled to testify Thursday before a House committee, but that hearing could be canceled or postponed amid a dispute about whether committee staff lawyers will question the attorney general.

Democrats have accused Barr of downplaying the seriousness of the evidence against the president.

In the report, Mueller described ten significant episodes of possible obstruction of justice, but said that due to long-standing Justice Department policy that says a sitting president cannot be indicted, and because of Justice Department practice regarding fairness toward those under investigation, his team did not reach a conclusion about whether the president had committed a crime.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/worl...82d3f3d96d5_story.html?utm_term=.555b90f3e35a

.

We already knew members of Mueller's team were upset with Barr's characterization of their work, but "what we didn't know until today is that Mueller was pissed," legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin said on CNN Tuesday night. New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman had another explanation: "Muller seems to have learned the lesson that a lot of people who have been around Donald Trump's world learned — and Mueller knows, because almost all of them were witnesses for him — that you have to put everything down on paper. This was not enough to just voice his concerns privately to Barr, there had to be a letter documenting it, and it's a stunning letter." Peter Weber

https://theweek.com/speedreads/8386...shocked-mueller-displeasure-barr-down-writing

Trump would have been charged with obstruction were he not president, hundreds of former federal prosecutors assert

More than 370 former federal prosecutors who worked in Republican and Democratic administrations have signed on to a statement asserting special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s findings would have produced obstruction charges against President Trump — if not for the office he held.

The statement — signed by myriad former career government employees as well as high-profile political appointees — offers a rebuttal to Attorney General William P. Barr’s determination that the evidence Mueller uncovered was “not sufficient” to establish that Trump committed a crime.

Mueller had declined to say one way or the other whether Trump should have been charged, citing a Justice Department legal opinion that sitting presidents cannot be indicted, as well as concerns about the fairness of accusing someone for whom there can be no court proceeding.

“Each of us believes that the conduct of President Trump described in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report would, in the case of any other person not covered by the Office of Legal Counsel policy against indicting a sitting President, result in multiple felony charges for obstruction of justice,” the former federal prosecutors wrote.

“We emphasize that these are not matters of close professional judgment,” they added. “Of course, there are potential defenses or arguments that could be raised in response to an indictment of the nature we describe here. . . . But, to look at these facts and say that a prosecutor could not probably sustain a conviction for obstruction of justice — the standard set out in Principles of Federal Prosecution — runs counter to logic and our experience.”

The statement is notable for the number of people who signed it — 375 as of Monday afternoon — and the positions and political affiliations of some on the list. It was posted online Monday afternoon; those signing it did not explicitly address what, if anything, they hope might happen next.

mong the high-profile signers are Bill Weld, a former U.S. attorney and Justice Department official in the Reagan administration who is running against Trump as a Republican; Donald Ayer, a former deputy attorney general in the George H.W. Bush Administration; John S. Martin, a former U.S. attorney and federal judge appointed to his posts by two Republican presidents; Paul Rosenzweig, who served as senior counsel to independent counsel Kenneth W. Starr; and Jeffrey Harris, who worked as the principal assistant to Rudolph W. Giuliani when he was at the Justice Department in the Reagan administration.

The list also includes more than 20 former U.S. attorneys and more than 100 people with at least 20 years of service at the Justice Department — most of them former career officials. The signers worked in every presidential administration since that of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The signatures were collected by the nonprofit group Protect Democracy, which counts Justice Department alumni among its staff and was contacted about the statement last week by a group of former federal prosecutors, said Justin Vail, an attorney at Protect Democracy.

“We strongly believe that Americans deserve to hear from the men and women who spent their careers weighing evidence and making decisions about whether it was sufficient to justify prosecution, so we agreed to send out a call for signatories,” Vail said. “The response was overwhelming. This effort reflects the voices of former prosecutors who have served at DOJ and signed the statement.”

FULL ARTICLE: https://www.washingtonpost.com/worl...fc2ee80027a_story.html?utm_term=.35b61911cf5d

.

More than 370 former federal prosecutors who worked in Republican and Democratic administrations have signed on to a statement asserting special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s findings would have produced obstruction charges against President Trump — if not for the office he held.

The statement — signed by myriad former career government employees as well as high-profile political appointees — offers a rebuttal to Attorney General William P. Barr’s determination that the evidence Mueller uncovered was “not sufficient” to establish that Trump committed a crime.

Mueller had declined to say one way or the other whether Trump should have been charged, citing a Justice Department legal opinion that sitting presidents cannot be indicted, as well as concerns about the fairness of accusing someone for whom there can be no court proceeding.

“Each of us believes that the conduct of President Trump described in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report would, in the case of any other person not covered by the Office of Legal Counsel policy against indicting a sitting President, result in multiple felony charges for obstruction of justice,” the former federal prosecutors wrote.

“We emphasize that these are not matters of close professional judgment,” they added. “Of course, there are potential defenses or arguments that could be raised in response to an indictment of the nature we describe here. . . . But, to look at these facts and say that a prosecutor could not probably sustain a conviction for obstruction of justice — the standard set out in Principles of Federal Prosecution — runs counter to logic and our experience.”

The statement is notable for the number of people who signed it — 375 as of Monday afternoon — and the positions and political affiliations of some on the list. It was posted online Monday afternoon; those signing it did not explicitly address what, if anything, they hope might happen next.

mong the high-profile signers are Bill Weld, a former U.S. attorney and Justice Department official in the Reagan administration who is running against Trump as a Republican; Donald Ayer, a former deputy attorney general in the George H.W. Bush Administration; John S. Martin, a former U.S. attorney and federal judge appointed to his posts by two Republican presidents; Paul Rosenzweig, who served as senior counsel to independent counsel Kenneth W. Starr; and Jeffrey Harris, who worked as the principal assistant to Rudolph W. Giuliani when he was at the Justice Department in the Reagan administration.

The list also includes more than 20 former U.S. attorneys and more than 100 people with at least 20 years of service at the Justice Department — most of them former career officials. The signers worked in every presidential administration since that of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The signatures were collected by the nonprofit group Protect Democracy, which counts Justice Department alumni among its staff and was contacted about the statement last week by a group of former federal prosecutors, said Justin Vail, an attorney at Protect Democracy.

“We strongly believe that Americans deserve to hear from the men and women who spent their careers weighing evidence and making decisions about whether it was sufficient to justify prosecution, so we agreed to send out a call for signatories,” Vail said. “The response was overwhelming. This effort reflects the voices of former prosecutors who have served at DOJ and signed the statement.”

FULL ARTICLE: https://www.washingtonpost.com/worl...fc2ee80027a_story.html?utm_term=.35b61911cf5d

.

Flynn: People tied to Trump, Congress tried to interfere in Russia probe

During his interviews with Special Counsel Robert Mueller's office, former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn told investigators that people with ties to the Trump administration and Congress contacted him in an attempt to interfere with the Russia investigation, Mueller wrote in newly unredacted court papers released Thursday. The messages could have "affected both his willingness to cooperate and the completeness of that cooperation," Mueller said, adding that "in some instances," his office was "unaware of the outreach until being alerted to it by the defendant." Flynn provided a recording of one of the voicemails he received, the filing said. In December 2017, Flynn pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about his conversations with Russia's ambassador.

Source: NBC News

.

During his interviews with Special Counsel Robert Mueller's office, former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn told investigators that people with ties to the Trump administration and Congress contacted him in an attempt to interfere with the Russia investigation, Mueller wrote in newly unredacted court papers released Thursday. The messages could have "affected both his willingness to cooperate and the completeness of that cooperation," Mueller said, adding that "in some instances," his office was "unaware of the outreach until being alerted to it by the defendant." Flynn provided a recording of one of the voicemails he received, the filing said. In December 2017, Flynn pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about his conversations with Russia's ambassador.

Source: NBC News

.

The House Judiciary Committee will hold hearings Monday afternoon on Special Counsel Robert Mueller's report, focusing on President Trump's potential obstruction of justice with former Nixon White House Counsel John Dean and some of the 1,000-plus former federal prosecutors who signed a letter saying Trump would face criminal charges if he were not president.

Monday's hearings kick off a week in which House Democrats hope to focus on Mueller's findings, believing the public is largely unaware of what he found.

On Tuesday, the House will vote on whether to authorize contempt cases against Attorney General William Barr and former White House Counsel Don McGahn; and

On Wednesday, the House Intelligence Committee will hold a hearing on the Russia part of Mueller's report.

Source: ABC News

It's taken me ten weeks to read it. I had to go and do some side reading, like the Justice Department policy. They need to put Mueller on the stand...

They need to put Mueller on the stand...

I'd like to see that also; but I'd like to have the questioning handled by skilled trial lawyers. Time is very limited in these hearings and most of the pols waste too much time (even those with law degrees) and tend not to ask pointed questions and maintain a flow that results in something.

I'd like to see that also; but I'd like to have the questioning handled by skilled trial lawyers. Time is very limited in these hearings and most of the pols waste too much time (even those with law degrees) and tend not to ask pointed questions and maintain a flow that results in something.

Yeah, but it was not until "The Watergate Hearings" before Congress - two years after the break in - that the public began to understand

#1 what was important about it: (Republican dirty tricks)

#2 what was criminal of the president (Nixon being a part of meetings several days after the break-in and, in effect, directing a coverup [he didn't actually say "cover it up for me" but there were enough "take care of it" and "be careful" for a truly neutral mind to say, he's telling them what to do]

#3 it was the testimony of people like Dean, Alexander Butterfield and others who let out little and big secrets, in the open air, that led the public and politicians to realize that it was true that the President of the United States directed the cover up of the illegal break in of the Democratic Party headuarters.

No-one will ever know if Nixon ordered the creation of The Plumbers, who were former CIA and FBI agents and anti-Castro Cuban exiles who were tasked to do "ratfucking" or dirty tricks. But he certainly knew that that was what certain people within his party did. He knew that that was what his party did. and if you hire certain people that's what they will do.

Examples of the Nixon dirty tricks? Follow Democratic Party operatives, see that they've gone into a Japanese restaurant and steal their shoes. Or go to northern Maine and New Hampshire where there are a lot of people who descend from people who crossed the river from Quebec. Fake a letter that uses the term "Canuck", suggesting that the Democratic party candidate is mentally ill. Then hint to the media cameramen to be outside his house the next morning. Like clockwork, that candidate came outside and was so angry and frustrated after months of dirty tricks, teared up. The REpubllican response? Oh, he can't be president, he's a crybaby. He's weak. Nixon won reelction a few months after news of the break in by a landslide: 49 to 1.

So when you hear Trump say "no collusion" what he's really saying is that he had nothing to do with ordering people to "collude" with Russia. But you hired people that had extensive experience and contact with Russia. You knew what they would do. And the second part of the Mueller report shows you tried to cover it up after the fact. That's a crime. That's an impeachable crime. That's an indictable crime. And you should not be president.

But after all that, I am not confident this can be pulled off. I don't think Pelosi thinks that it can be pulled off in congress. I think she wants to win the White House, retain the House and reclaim the Senate next year. And that is because of the tactics from the REpublicans.

First, thanks for your comments.Yeah, but it was not until "The Watergate Hearings" before Congress - two years after the break in - that the public began to understand

Yeah, you're right . . . it took a while before Clarity arrived. But Howard Baker's pointed question brought shit home: “What did the president know and when did he know it?”

.

First, thanks for your comments.

Yeah, you're right . . . it took a while before Clarity arrived. But Howard Baker's pointed question brought shit home: “What did the president know and when did he know it?”.

I'm saying that was the question in 1973. But the question for 2019 and 2020 should be: What did the Vice President know and when did he know it? Because if he knew during the campaign - he can't be president if there is an impeachment and conviction at 1600 Pennsylvania Av.

I'm saying that was the question in 1973. But the question for 2019 and 2020 should be: What did the Vice President know and when did he know it? Because if he knew during the campaign - he can't be president if there is an impeachment and conviction at 1600 Pennsylvania Av.

I think you're asking a good question of the Vice President, especially since in the event of a Trump impeachment it would put Pence in a hellava Pinch!

But the kind of questioning I have in mind relates more to well planned, systematic questioning designed to elicit the responses that one has planned to receive within the time frame that you have to work with.

In other words, you already know the answers before you ask the questions (you don't ask questions that you don't know the answers to) and you design the questions with the idea of walking the witness right down the path that you want him/her to walk. Of course, this means you have to have a great command of the evidence and a lot of homework carefully designing the examination. If done properly (and can fit into the ridiculously small time frames of congressional hearings) there could be opportunities for the "Zingers" like Howard Baker's.

I think you're asking a good question of the Vice President, especially since in the event of a Trump impeachment it would put Pence in a hellava Pinch!

But the kind of questioning I have in mind relates more to well planned, systematic questioning designed to elicit the responses that one has planned to receive within the time frame that you have to work with.

In other words, you already know the answers before you ask the questions (you don't ask questions that you don't know the answers to) and you design the questions with the idea of walking the witness right down the path that you want him/her to walk. Of course, this means you have to have a great command of the evidence and a lot of homework carefully designing the examination. If done properly (and can fit into the ridiculously small time frames of congressional hearings) there could be opportunities for the "Zingers" like Howard Baker's.

Congress - wait, want a joke? What's a group of baboons called? A congress - has enough good lawyers to do the job. But I'd bet that all of Trump's people have been practicing their answers for two years. In other words, after watching the Attorney General manover like he did, I think such questioning before subcommittees might not lead to any surprises. I just don't know. It's all theater.

This thing has to go to November 2020. We will have to brace ourselves for what policies come down the pipeline until then.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 222

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 54

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 135

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 383