White contractors wouldn’t remove Confederate statues.

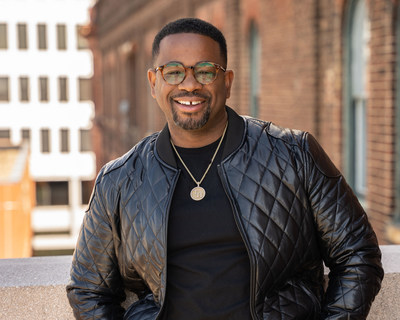

So a Black man did it.

RICHMOND — Workers in bright yellow vests circled up in the morning chill. Some clutched cups of Starbucks coffee, a last comfort before beginning the hard work of dismantling a statue of Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill in the middle of an intersection.

As a small group of Confederate heritage defenders assembled nearby — at least one of them armed — city safety coordinator Miles Jones lectured the work crew on wearing hard hats and eye protection. And who, he asked, would be the site supervisor? A bearded man in Ray-Ban sunglasses and a Norfolk State University sweatshirt stepped forward.

“What’s your name, sir?” Jones asked.

“Devon Henry.”

“Devon Hen—” Jones began, then dropped his voice respectfully. “Oh, Mr. Henry. Of course.”

The name carries weight in Richmond these days. Over the past three years, as the former capital of the Confederacy has taken down more than a dozen monuments to the Lost Cause, Henry — who is Black — has overseen all the work.

He didn’t seek the job. He had never paid much attention to Civil War history. City and state officials said they turned to Team Henry Enterprises after a long list of bigger contractors — all White-owned — said they wanted no part of taking down Confederate statues.

For a Black man to step in carried enormous risk. Henry concealed the name of his company for a time and long shunned media interviews. He has endured death threats, seen employees walk away and been told by others in the industry that his future is ruined. He started wearing a bulletproof vest on job sites and got a permit to carry a concealed firearm for protection.

The drama interrupted Henry’s careful efforts to build his business. But after removing 24 monuments in Virginia and North Carolina, Henry, 45, has grown more comfortable with his role in enabling a historic reckoning with social injustice across the South. The threats haven’t let up; Henry has simply learned to live with them.

“My head’s in a different place now,” he said. “It’s like, I’m not scared to cross the street, but I’m always going to look both ways, right? So I’m not totally oblivious to who I am and what I’ve done, but I’m just not letting fear kind of drive what I do.”

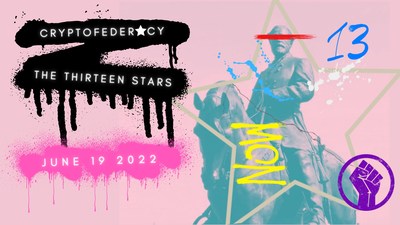

Over and over, history-minded friends directed Henry to the words of John Mitchell Jr., the civil rights pioneer and editor of the Richmond Planet, a groundbreaking African American newspaper. In 1890, the year the state erected an enormous statue of Robert E. Lee on what would become Monument Avenue, Mitchell wrote about the resilience of the Black person in society.

“The Negro … put up the Lee monument,” Mitchell wrote, “and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

****

The call that changed Henry’s life came in the middle of a business meeting in early June 2020. He ignored it, at first. But his phone kept going off, and finally a friend texted — you might want to pick up.

On the line was Clark Mercer, the chief of staff for then-Gov. Ralph Northam, with a wild proposition: Would Henry’s construction company be willing to oversee the dismantling of the giant statue of Lee on state-owned property along Monument Avenue?

Such a thing was nowhere on Henry’s radar screen. His company was experienced at building things, and at preparing sites for construction.

Outside of work, though, change was in the air. Partly in reaction to the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the General Assembly had passed a bill early in 2020 to allow localities to take down Confederate statues. That May, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police touched off nationwide racial justice protests that in Richmond focused on Monument Avenue and its iconic memorials.

Northam, a Democrat, decided it was time to act. Protesters and police were clashing every night. He wanted to move fast.

Mercer and Henry had met some time before at an event at Norfolk State, Henry’s alma mater and where he sits on the board of visitors. Now Mercer confessed that he was reaching out because he was desperate. Everyone else had turned him down.

“I was pretty forthcoming that we hadn’t been able to find anybody to take on the job,” Mercer said in an interview. In fact, the responses from other contractors were “pretty overtly racist,” he said, including language that he found threatening. “Devon seemed to understand the magnitude of what I was asking him.”

Henry never paid much attention to Confederate monuments. Growing up in Hampton and Newport News, he went to Robert E. Lee Elementary School, but the name meant little to him. There were bigger concerns.

His mother had been only 16 when Henry was born in Lumberton, N.C. She moved to Hampton Roads and took up work in McDonald’s restaurants to support herself and her baby. At 14, Devon began taking shifts at McDonald’s as well.

He got good grades in school and developed an ambition to be a doctor. But after majoring in biology at Norfolk State, Henry found himself drawn to business. After college, he got into the corporate leadership program at General Electric, and the company paid for him to get a master’s degree as he worked in its infrastructure division. He immersed himself in biographies of business leaders — such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s.

His mother, meanwhile, had taken advantage of training programs at McDonald’s, climbed the ladder and then — by the time Henry was grown — became a franchisee. She wound up owning five restaurants in the Richmond area.

Her example of hard work pushed Henry. When he learned of a small construction business going up for sale in the city of Suffolk, he made a snap decision to leave G.E. and put all his savings into buying it. Henry and his wife commuted 90 minutes every day from Richmond to Suffolk — in separate cars so one could get back and pick up their daughter from school.

White contractors wouldn’t remove Confederate statues. So a Black man did it.

RICHMOND — Workers in bright yellow vests circled up in the morning chill. Some clutched cups of Starbucks coffee, a last comfort before beginning the hard work of dismantling a statue of Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill in the middle of an intersection.

As a small group of Confederate heritage defenders assembled nearby — at least one of them armed — city safety coordinator Miles Jones lectured the work crew on wearing hard hats and eye protection. And who, he asked, would be the site supervisor? A bearded man in Ray-Ban sunglasses and a Norfolk State University sweatshirt stepped forward.

“What’s your name, sir?” Jones asked.

“Devon Henry.”

“Devon Hen—” Jones began, then dropped his voice respectfully. “Oh, Mr. Henry. Of course.”

The name carries weight in Richmond these days. Over the past three years, as the former capital of the Confederacy has taken down more than a dozen monuments to the Lost Cause, Henry — who is Black — has overseen all the work.

He didn’t seek the job. He had never paid much attention to Civil War history. City and state officials said they turned to Team Henry Enterprises after a long list of bigger contractors — all White-owned — said they wanted no part of taking down Confederate statues.

For a Black man to step in carried enormous risk. Henry concealed the name of his company for a time and long shunned media interviews. He has endured death threats, seen employees walk away and been told by others in the industry that his future is ruined. He started wearing a bulletproof vest on job sites and got a permit to carry a concealed firearm for protection.

The drama interrupted Henry’s careful efforts to build his business. But after removing 24 monuments in Virginia and North Carolina, Henry, 45, has grown more comfortable with his role in enabling a historic reckoning with social injustice across the South. The threats haven’t let up; Henry has simply learned to live with them.

“My head’s in a different place now,” he said. “It’s like, I’m not scared to cross the street, but I’m always going to look both ways, right? So I’m not totally oblivious to who I am and what I’ve done, but I’m just not letting fear kind of drive what I do.”

Over and over, history-minded friends directed Henry to the words of John Mitchell Jr., the civil rights pioneer and editor of the Richmond Planet, a groundbreaking African American newspaper. In 1890, the year the state erected an enormous statue of Robert E. Lee on what would become Monument Avenue, Mitchell wrote about the resilience of the Black person in society.

“The Negro … put up the Lee monument,” Mitchell wrote, “and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

****

The call that changed Henry’s life came in the middle of a business meeting in early June 2020. He ignored it, at first. But his phone kept going off, and finally a friend texted — you might want to pick up.

On the line was Clark Mercer, the chief of staff for then-Gov. Ralph Northam, with a wild proposition: Would Henry’s construction company be willing to oversee the dismantling of the giant statue of Lee on state-owned property along Monument Avenue?

Such a thing was nowhere on Henry’s radar screen. His company was experienced at building things, and at preparing sites for construction.

Outside of work, though, change was in the air. Partly in reaction to the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the General Assembly had passed a bill early in 2020 to allow localities to take down Confederate statues. That May, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police touched off nationwide racial justice protests that in Richmond focused on Monument Avenue and its iconic memorials.

Northam, a Democrat, decided it was time to act. Protesters and police were clashing every night. He wanted to move fast.

Mercer and Henry had met some time before at an event at Norfolk State, Henry’s alma mater and where he sits on the board of visitors. Now Mercer confessed that he was reaching out because he was desperate. Everyone else had turned him down.

“I was pretty forthcoming that we hadn’t been able to find anybody to take on the job,” Mercer said in an interview. In fact, the responses from other contractors were “pretty overtly racist,” he said, including language that he found threatening. “Devon seemed to understand the magnitude of what I was asking him.”

Henry never paid much attention to Confederate monuments. Growing up in Hampton and Newport News, he went to Robert E. Lee Elementary School, but the name meant little to him. There were bigger concerns.

His mother had been only 16 when Henry was born in Lumberton, N.C. She moved to Hampton Roads and took up work in McDonald’s restaurants to support herself and her baby. At 14, Devon began taking shifts at McDonald’s as well.

He got good grades in school and developed an ambition to be a doctor. But after majoring in biology at Norfolk State, Henry found himself drawn to business. After college, he got into the corporate leadership program at General Electric, and the company paid for him to get a master’s degree as he worked in its infrastructure division. He immersed himself in biographies of business leaders — such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s.

His mother, meanwhile, had taken advantage of training programs at McDonald’s, climbed the ladder and then — by the time Henry was grown — became a franchisee. She wound up owning five restaurants in the Richmond area.

Her example of hard work pushed Henry. When he learned of a small construction business going up for sale in the city of Suffolk, he made a snap decision to leave G.E. and put all his savings into buying it. Henry and his wife commuted 90 minutes every day from Richmond to Suffolk — in separate cars so one could get back and pick up their daughter from school.

White contractors wouldn’t remove Confederate statues. So a Black man did it.

RICHMOND — Workers in bright yellow vests circled up in the morning chill. Some clutched cups of Starbucks coffee, a last comfort before beginning the hard work of dismantling a statue of Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill in the middle of an intersection.

As a small group of Confederate heritage defenders assembled nearby — at least one of them armed — city safety coordinator Miles Jones lectured the work crew on wearing hard hats and eye protection. And who, he asked, would be the site supervisor? A bearded man in Ray-Ban sunglasses and a Norfolk State University sweatshirt stepped forward.

“What’s your name, sir?” Jones asked.

“Devon Henry.”

“Devon Hen—” Jones began, then dropped his voice respectfully. “Oh, Mr. Henry. Of course.”

The name carries weight in Richmond these days. Over the past three years, as the former capital of the Confederacy has taken down more than a dozen monuments to the Lost Cause, Henry — who is Black — has overseen all the work.

He didn’t seek the job. He had never paid much attention to Civil War history. City and state officials said they turned to Team Henry Enterprises after a long list of bigger contractors — all White-owned — said they wanted no part of taking down Confederate statues.

For a Black man to step in carried enormous risk. Henry concealed the name of his company for a time and long shunned media interviews. He has endured death threats, seen employees walk away and been told by others in the industry that his future is ruined. He started wearing a bulletproof vest on job sites and got a permit to carry a concealed firearm for protection.

The drama interrupted Henry’s careful efforts to build his business. But after removing 24 monuments in Virginia and North Carolina, Henry, 45, has grown more comfortable with his role in enabling a historic reckoning with social injustice across the South. The threats haven’t let up; Henry has simply learned to live with them.

“My head’s in a different place now,” he said. “It’s like, I’m not scared to cross the street, but I’m always going to look both ways, right? So I’m not totally oblivious to who I am and what I’ve done, but I’m just not letting fear kind of drive what I do.”

Over and over, history-minded friends directed Henry to the words of John Mitchell Jr., the civil rights pioneer and editor of the Richmond Planet, a groundbreaking African American newspaper. In 1890, the year the state erected an enormous statue of Robert E. Lee on what would become Monument Avenue, Mitchell wrote about the resilience of the Black person in society.

“The Negro … put up the Lee monument,” Mitchell wrote, “and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

****

The call that changed Henry’s life came in the middle of a business meeting in early June 2020. He ignored it, at first. But his phone kept going off, and finally a friend texted — you might want to pick up.

On the line was Clark Mercer, the chief of staff for then-Gov. Ralph Northam, with a wild proposition: Would Henry’s construction company be willing to oversee the dismantling of the giant statue of Lee on state-owned property along Monument Avenue?

Such a thing was nowhere on Henry’s radar screen. His company was experienced at building things, and at preparing sites for construction.

Outside of work, though, change was in the air. Partly in reaction to the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the General Assembly had passed a bill early in 2020 to allow localities to take down Confederate statues. That May, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police touched off nationwide racial justice protests that in Richmond focused on Monument Avenue and its iconic memorials.

Northam, a Democrat, decided it was time to act. Protesters and police were clashing every night. He wanted to move fast.

Mercer and Henry had met some time before at an event at Norfolk State, Henry’s alma mater and where he sits on the board of visitors. Now Mercer confessed that he was reaching out because he was desperate. Everyone else had turned him down.

“I was pretty forthcoming that we hadn’t been able to find anybody to take on the job,” Mercer said in an interview. In fact, the responses from other contractors were “pretty overtly racist,” he said, including language that he found threatening. “Devon seemed to understand the magnitude of what I was asking him.”

Henry never paid much attention to Confederate monuments. Growing up in Hampton and Newport News, he went to Robert E. Lee Elementary School, but the name meant little to him. There were bigger concerns.

His mother had been only 16 when Henry was born in Lumberton, N.C. She moved to Hampton Roads and took up work in McDonald’s restaurants to support herself and her baby. At 14, Devon began taking shifts at McDonald’s as well.

He got good grades in school and developed an ambition to be a doctor. But after majoring in biology at Norfolk State, Henry found himself drawn to business. After college, he got into the corporate leadership program at General Electric, and the company paid for him to get a master’s degree as he worked in its infrastructure division. He immersed himself in biographies of business leaders — such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s.

His mother, meanwhile, had taken advantage of training programs at McDonald’s, climbed the ladder and then — by the time Henry was grown — became a franchisee. She wound up owning five restaurants in the Richmond area.

Her example of hard work pushed Henry. When he learned of a small construction business going up for sale in the city of Suffolk, he made a snap decision to leave G.E. and put all his savings into buying it. Henry and his wife commuted 90 minutes every day from Richmond to Suffolk — in separate cars so one could get back and pick up their daughter from school.

Washington Post

So a Black man did it.

RICHMOND — Workers in bright yellow vests circled up in the morning chill. Some clutched cups of Starbucks coffee, a last comfort before beginning the hard work of dismantling a statue of Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill in the middle of an intersection.

As a small group of Confederate heritage defenders assembled nearby — at least one of them armed — city safety coordinator Miles Jones lectured the work crew on wearing hard hats and eye protection. And who, he asked, would be the site supervisor? A bearded man in Ray-Ban sunglasses and a Norfolk State University sweatshirt stepped forward.

“What’s your name, sir?” Jones asked.

“Devon Henry.”

“Devon Hen—” Jones began, then dropped his voice respectfully. “Oh, Mr. Henry. Of course.”

The name carries weight in Richmond these days. Over the past three years, as the former capital of the Confederacy has taken down more than a dozen monuments to the Lost Cause, Henry — who is Black — has overseen all the work.

He didn’t seek the job. He had never paid much attention to Civil War history. City and state officials said they turned to Team Henry Enterprises after a long list of bigger contractors — all White-owned — said they wanted no part of taking down Confederate statues.

For a Black man to step in carried enormous risk. Henry concealed the name of his company for a time and long shunned media interviews. He has endured death threats, seen employees walk away and been told by others in the industry that his future is ruined. He started wearing a bulletproof vest on job sites and got a permit to carry a concealed firearm for protection.

The drama interrupted Henry’s careful efforts to build his business. But after removing 24 monuments in Virginia and North Carolina, Henry, 45, has grown more comfortable with his role in enabling a historic reckoning with social injustice across the South. The threats haven’t let up; Henry has simply learned to live with them.

“My head’s in a different place now,” he said. “It’s like, I’m not scared to cross the street, but I’m always going to look both ways, right? So I’m not totally oblivious to who I am and what I’ve done, but I’m just not letting fear kind of drive what I do.”

Over and over, history-minded friends directed Henry to the words of John Mitchell Jr., the civil rights pioneer and editor of the Richmond Planet, a groundbreaking African American newspaper. In 1890, the year the state erected an enormous statue of Robert E. Lee on what would become Monument Avenue, Mitchell wrote about the resilience of the Black person in society.

“The Negro … put up the Lee monument,” Mitchell wrote, “and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

****

The call that changed Henry’s life came in the middle of a business meeting in early June 2020. He ignored it, at first. But his phone kept going off, and finally a friend texted — you might want to pick up.

On the line was Clark Mercer, the chief of staff for then-Gov. Ralph Northam, with a wild proposition: Would Henry’s construction company be willing to oversee the dismantling of the giant statue of Lee on state-owned property along Monument Avenue?

Such a thing was nowhere on Henry’s radar screen. His company was experienced at building things, and at preparing sites for construction.

Outside of work, though, change was in the air. Partly in reaction to the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the General Assembly had passed a bill early in 2020 to allow localities to take down Confederate statues. That May, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police touched off nationwide racial justice protests that in Richmond focused on Monument Avenue and its iconic memorials.

Northam, a Democrat, decided it was time to act. Protesters and police were clashing every night. He wanted to move fast.

Mercer and Henry had met some time before at an event at Norfolk State, Henry’s alma mater and where he sits on the board of visitors. Now Mercer confessed that he was reaching out because he was desperate. Everyone else had turned him down.

“I was pretty forthcoming that we hadn’t been able to find anybody to take on the job,” Mercer said in an interview. In fact, the responses from other contractors were “pretty overtly racist,” he said, including language that he found threatening. “Devon seemed to understand the magnitude of what I was asking him.”

Henry never paid much attention to Confederate monuments. Growing up in Hampton and Newport News, he went to Robert E. Lee Elementary School, but the name meant little to him. There were bigger concerns.

His mother had been only 16 when Henry was born in Lumberton, N.C. She moved to Hampton Roads and took up work in McDonald’s restaurants to support herself and her baby. At 14, Devon began taking shifts at McDonald’s as well.

He got good grades in school and developed an ambition to be a doctor. But after majoring in biology at Norfolk State, Henry found himself drawn to business. After college, he got into the corporate leadership program at General Electric, and the company paid for him to get a master’s degree as he worked in its infrastructure division. He immersed himself in biographies of business leaders — such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s.

His mother, meanwhile, had taken advantage of training programs at McDonald’s, climbed the ladder and then — by the time Henry was grown — became a franchisee. She wound up owning five restaurants in the Richmond area.

Her example of hard work pushed Henry. When he learned of a small construction business going up for sale in the city of Suffolk, he made a snap decision to leave G.E. and put all his savings into buying it. Henry and his wife commuted 90 minutes every day from Richmond to Suffolk — in separate cars so one could get back and pick up their daughter from school.

White contractors wouldn’t remove Confederate statues. So a Black man did it.

RICHMOND — Workers in bright yellow vests circled up in the morning chill. Some clutched cups of Starbucks coffee, a last comfort before beginning the hard work of dismantling a statue of Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill in the middle of an intersection.

As a small group of Confederate heritage defenders assembled nearby — at least one of them armed — city safety coordinator Miles Jones lectured the work crew on wearing hard hats and eye protection. And who, he asked, would be the site supervisor? A bearded man in Ray-Ban sunglasses and a Norfolk State University sweatshirt stepped forward.

“What’s your name, sir?” Jones asked.

“Devon Henry.”

“Devon Hen—” Jones began, then dropped his voice respectfully. “Oh, Mr. Henry. Of course.”

The name carries weight in Richmond these days. Over the past three years, as the former capital of the Confederacy has taken down more than a dozen monuments to the Lost Cause, Henry — who is Black — has overseen all the work.

He didn’t seek the job. He had never paid much attention to Civil War history. City and state officials said they turned to Team Henry Enterprises after a long list of bigger contractors — all White-owned — said they wanted no part of taking down Confederate statues.

For a Black man to step in carried enormous risk. Henry concealed the name of his company for a time and long shunned media interviews. He has endured death threats, seen employees walk away and been told by others in the industry that his future is ruined. He started wearing a bulletproof vest on job sites and got a permit to carry a concealed firearm for protection.

The drama interrupted Henry’s careful efforts to build his business. But after removing 24 monuments in Virginia and North Carolina, Henry, 45, has grown more comfortable with his role in enabling a historic reckoning with social injustice across the South. The threats haven’t let up; Henry has simply learned to live with them.

“My head’s in a different place now,” he said. “It’s like, I’m not scared to cross the street, but I’m always going to look both ways, right? So I’m not totally oblivious to who I am and what I’ve done, but I’m just not letting fear kind of drive what I do.”

Over and over, history-minded friends directed Henry to the words of John Mitchell Jr., the civil rights pioneer and editor of the Richmond Planet, a groundbreaking African American newspaper. In 1890, the year the state erected an enormous statue of Robert E. Lee on what would become Monument Avenue, Mitchell wrote about the resilience of the Black person in society.

“The Negro … put up the Lee monument,” Mitchell wrote, “and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

****

The call that changed Henry’s life came in the middle of a business meeting in early June 2020. He ignored it, at first. But his phone kept going off, and finally a friend texted — you might want to pick up.

On the line was Clark Mercer, the chief of staff for then-Gov. Ralph Northam, with a wild proposition: Would Henry’s construction company be willing to oversee the dismantling of the giant statue of Lee on state-owned property along Monument Avenue?

Such a thing was nowhere on Henry’s radar screen. His company was experienced at building things, and at preparing sites for construction.

Outside of work, though, change was in the air. Partly in reaction to the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the General Assembly had passed a bill early in 2020 to allow localities to take down Confederate statues. That May, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police touched off nationwide racial justice protests that in Richmond focused on Monument Avenue and its iconic memorials.

Northam, a Democrat, decided it was time to act. Protesters and police were clashing every night. He wanted to move fast.

Mercer and Henry had met some time before at an event at Norfolk State, Henry’s alma mater and where he sits on the board of visitors. Now Mercer confessed that he was reaching out because he was desperate. Everyone else had turned him down.

“I was pretty forthcoming that we hadn’t been able to find anybody to take on the job,” Mercer said in an interview. In fact, the responses from other contractors were “pretty overtly racist,” he said, including language that he found threatening. “Devon seemed to understand the magnitude of what I was asking him.”

Henry never paid much attention to Confederate monuments. Growing up in Hampton and Newport News, he went to Robert E. Lee Elementary School, but the name meant little to him. There were bigger concerns.

His mother had been only 16 when Henry was born in Lumberton, N.C. She moved to Hampton Roads and took up work in McDonald’s restaurants to support herself and her baby. At 14, Devon began taking shifts at McDonald’s as well.

He got good grades in school and developed an ambition to be a doctor. But after majoring in biology at Norfolk State, Henry found himself drawn to business. After college, he got into the corporate leadership program at General Electric, and the company paid for him to get a master’s degree as he worked in its infrastructure division. He immersed himself in biographies of business leaders — such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s.

His mother, meanwhile, had taken advantage of training programs at McDonald’s, climbed the ladder and then — by the time Henry was grown — became a franchisee. She wound up owning five restaurants in the Richmond area.

Her example of hard work pushed Henry. When he learned of a small construction business going up for sale in the city of Suffolk, he made a snap decision to leave G.E. and put all his savings into buying it. Henry and his wife commuted 90 minutes every day from Richmond to Suffolk — in separate cars so one could get back and pick up their daughter from school.

White contractors wouldn’t remove Confederate statues. So a Black man did it.

RICHMOND — Workers in bright yellow vests circled up in the morning chill. Some clutched cups of Starbucks coffee, a last comfort before beginning the hard work of dismantling a statue of Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill in the middle of an intersection.

As a small group of Confederate heritage defenders assembled nearby — at least one of them armed — city safety coordinator Miles Jones lectured the work crew on wearing hard hats and eye protection. And who, he asked, would be the site supervisor? A bearded man in Ray-Ban sunglasses and a Norfolk State University sweatshirt stepped forward.

“What’s your name, sir?” Jones asked.

“Devon Henry.”

“Devon Hen—” Jones began, then dropped his voice respectfully. “Oh, Mr. Henry. Of course.”

The name carries weight in Richmond these days. Over the past three years, as the former capital of the Confederacy has taken down more than a dozen monuments to the Lost Cause, Henry — who is Black — has overseen all the work.

He didn’t seek the job. He had never paid much attention to Civil War history. City and state officials said they turned to Team Henry Enterprises after a long list of bigger contractors — all White-owned — said they wanted no part of taking down Confederate statues.

For a Black man to step in carried enormous risk. Henry concealed the name of his company for a time and long shunned media interviews. He has endured death threats, seen employees walk away and been told by others in the industry that his future is ruined. He started wearing a bulletproof vest on job sites and got a permit to carry a concealed firearm for protection.

The drama interrupted Henry’s careful efforts to build his business. But after removing 24 monuments in Virginia and North Carolina, Henry, 45, has grown more comfortable with his role in enabling a historic reckoning with social injustice across the South. The threats haven’t let up; Henry has simply learned to live with them.

“My head’s in a different place now,” he said. “It’s like, I’m not scared to cross the street, but I’m always going to look both ways, right? So I’m not totally oblivious to who I am and what I’ve done, but I’m just not letting fear kind of drive what I do.”

Over and over, history-minded friends directed Henry to the words of John Mitchell Jr., the civil rights pioneer and editor of the Richmond Planet, a groundbreaking African American newspaper. In 1890, the year the state erected an enormous statue of Robert E. Lee on what would become Monument Avenue, Mitchell wrote about the resilience of the Black person in society.

“The Negro … put up the Lee monument,” Mitchell wrote, “and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

****

The call that changed Henry’s life came in the middle of a business meeting in early June 2020. He ignored it, at first. But his phone kept going off, and finally a friend texted — you might want to pick up.

On the line was Clark Mercer, the chief of staff for then-Gov. Ralph Northam, with a wild proposition: Would Henry’s construction company be willing to oversee the dismantling of the giant statue of Lee on state-owned property along Monument Avenue?

Such a thing was nowhere on Henry’s radar screen. His company was experienced at building things, and at preparing sites for construction.

Outside of work, though, change was in the air. Partly in reaction to the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the General Assembly had passed a bill early in 2020 to allow localities to take down Confederate statues. That May, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police touched off nationwide racial justice protests that in Richmond focused on Monument Avenue and its iconic memorials.

Northam, a Democrat, decided it was time to act. Protesters and police were clashing every night. He wanted to move fast.

Mercer and Henry had met some time before at an event at Norfolk State, Henry’s alma mater and where he sits on the board of visitors. Now Mercer confessed that he was reaching out because he was desperate. Everyone else had turned him down.

“I was pretty forthcoming that we hadn’t been able to find anybody to take on the job,” Mercer said in an interview. In fact, the responses from other contractors were “pretty overtly racist,” he said, including language that he found threatening. “Devon seemed to understand the magnitude of what I was asking him.”

Henry never paid much attention to Confederate monuments. Growing up in Hampton and Newport News, he went to Robert E. Lee Elementary School, but the name meant little to him. There were bigger concerns.

His mother had been only 16 when Henry was born in Lumberton, N.C. She moved to Hampton Roads and took up work in McDonald’s restaurants to support herself and her baby. At 14, Devon began taking shifts at McDonald’s as well.

He got good grades in school and developed an ambition to be a doctor. But after majoring in biology at Norfolk State, Henry found himself drawn to business. After college, he got into the corporate leadership program at General Electric, and the company paid for him to get a master’s degree as he worked in its infrastructure division. He immersed himself in biographies of business leaders — such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s.

His mother, meanwhile, had taken advantage of training programs at McDonald’s, climbed the ladder and then — by the time Henry was grown — became a franchisee. She wound up owning five restaurants in the Richmond area.

Her example of hard work pushed Henry. When he learned of a small construction business going up for sale in the city of Suffolk, he made a snap decision to leave G.E. and put all his savings into buying it. Henry and his wife commuted 90 minutes every day from Richmond to Suffolk — in separate cars so one could get back and pick up their daughter from school.

Washington Post