For the overwhelmingly majority of you peeps who will never read the articles below, but rush to see an ass-to-mouth sex video; here is the CliffNotes version: A Black man in Mississippi is tried six times for a murder using phantom bullshit evidence. The trials were so racially corrupt and biased that the Mississippi Supreme court invalidated most of the trials. The Mississippi prosecutor presiding over the six trials excluded every Black juror that he could during the six trials. Mr. Curtis Flowers (the defendant) anguished trials dilemma is now in front of SCOTUS. Clinically insane sambo coon clarence thomas emerged from his septic tank silence to ask a question which indicates that he has no problem with a racist cac prosecutor throwing all Black citizens off of a jury in a death penalty trial of a Black man. Sambo thomas' balls have already been cut-off by his cac sponsers; when will someone quicken his permanent demise & put him out of his self-loathing misery; he is a world historical disgrace for the ages

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Mississippi Man Tried

Six Times for the Same Crime

May 20, 2018 | by David Leonhardt | https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/20/opinion/mississippi-curtis-flowers-trial.html

Curtis Flowers, left, leaving the Montgomery County Courthouse in Winona, Miss.

One morning nearly 22 years ago, four employees of a furniture store in a small Mississippi town were shot to death. For months afterward, local law-enforcement seemed stumped by the crime. Eventually, the top prosecutor — Doug Evans — charged a former store employee, Curtis Flowers, a black man who had no criminal record.

The case since then has been unlike any other I’ve ever heard of. Evans has put Flowers on trial six separate times — even though no gun, fingerprints or other physical evidence ties Flowers to the crime and no witness even puts him at the store that day.

At each of the first three trials, Flowers was convicted, but the Mississippi Supreme Court threw out all three convictions. The first two times, it cited misconduct by Evans during the trial, and the third time it found that Evans had kept African-Americans off the jury. The justices called it as bad a case of such racial discrimination “as we have ever seen.”

The fourth trial was the first to have more than one black juror, and it ended with a hung jury. The fifth also had multiple black jurors and likewise ended in a mistrial. The sixth trial had only one black juror, and Flowers was convicted, thanks largely to dubious circumstantial testimony that Evans had coached witnesses to give. I see no good reason to believe that Curtis Flowers is guilty.

Yet today he sits in solitary confinement, on death row, in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison. He is serving his 22nd straight year behind bars, having never been released between convictions. He will turn 48 years old next week. His parents continue to visit him as often as possible.

A death row cell at the Mississippi State Prison in Parchman.

His heartbreaking, enraging story is the subject of a new podcast — the second season of “In the Dark,” led by Madeleine Baran of American Public Media — that’s already been downloaded more than two million times. The reporting and storytelling are fantastic, and I can’t capture all of it here. If you aren’t already listening to the podcast, I recommend it.

While the Flowers case is shocking in its details, it is all too typical in its broad strokes: The United States suffers from a crisis of unjust imprisonment. The crisis has been caused partly by powerful, unaccountable prosecutors, like Doug Evans. And the costs are borne overwhelmingly by black men, like Flowers.

Racist prosecutor Doug Evans, center, interviewing a witness in the sixth trial of Curtis Flowers.

We now know that dozens of innocent people have been executed in recent decades. Many others languish behind bars. My colleague Nicholas Kristof, in his latest column, told the story of Kevin Cooper, who’s on death row in California because of highly questionable evidence. Cases like these are the most extreme part of our mass-incarceration problem. As the legal scholar Michelle Alexander has noted, a larger share of black Americans are imprisoned than black South Africans were during apartheid. “A human rights nightmare is occurring on our watch,” she has written.

When Americans today look back on the past, many of us wonder how our ancestors could have tolerated blatant injustices — like child labor, Jim Crow or male-only voting — for so long. When future generations look back on our era, I expect they will ask a similar question. They will be outraged that we forcibly confined a couple million of our fellow human beings to cages, often for no good reason.

President Trump and his attorney general, Jeff Sessions, are trying to make the problem even worse, by locking up ever more people. But Trump and Sessions can’t squelch the burgeoning, bipartisan movement for criminal-justice reform. They can’t, because as the recent Pulitzer-winning author James Forman Jr. points out, criminal justice happens mostly at the local and state levels. “We should always remember that the fight is going to be at the local level,” Forman told NPR’s Terry Gross, “and, there, we continue to win.”

To take one example, manufactured jailhouse confessions are a common part of wrongful prosecutions (and are central to the Flowers case). With a shocking frequency, prosecutors and police coax so-called snitches to lie outright about what other prisoners say. In response, Texas enacted a law last year requiring the tracking of snitches and the disclosure of any plea deals to defense attorneys, who can then call the testimony into question in front of a jury. Rebecca Brown of the Innocence Project told me that the Texas law was “excellent” — and that the Illinois legislature had passed an even better version, awaiting the governor’s signature.

Elsewhere, some district attorneys are trying to make the system fairer on their own. It’s happening in Brooklyn, Chicago, Philadelphia and other cities. Most prosecutors, after all, are decent, ethical public servants. One change involves “open-file” policies, which give the defense attorney access to all of the evidence in a case. That may seem like an obvious step, and it’s the norm in civil trials. Yet it remains rare in criminal trials.

I don’t want to exaggerate the recent progress. As you read this column, thousands upon thousands of American citizens sit behind bars, unjustly denied their freedom. “Ooooh, I miss Curtis,” his devastated father, Archie Flowers, says on the podcast. “Yes. It is rough. Rough, rough, rough, rough.”

But the Flowers family refuses to give up hoping for justice. Curtis Flowers’s sixth conviction is still being appealed, and new evidence — uncovered by the podcast — seems likely to help that appeal.

If the Flowers family won’t give in to despair, nobody else should, either.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

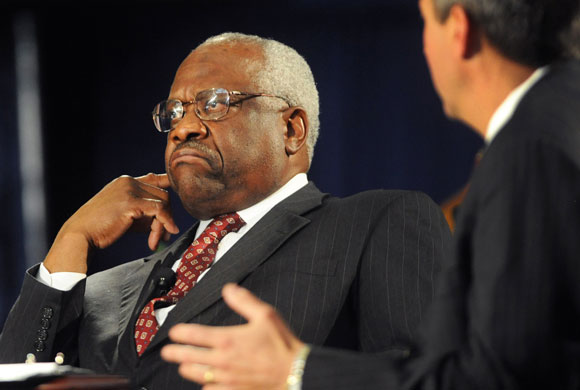

Clarence Thomas Breaks a Three-Year Silence at Supreme Court Hearing On Curtis Flowers

March 21, 2019 | by Adam Liptak | https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/us/politics/clarence-thomas-speaks-supreme-court.html

WASHINGTON — For the first 55 minutes of a Supreme Court argument on Wednesday about racial discrimination in jury selection, the justices seemed united in their view that a white Mississippi prosecutor had violated the Constitution in his determined efforts to exclude black jurors from the six trials of Curtis Flowers, who was convicted of murdering four people in a furniture store.

As Mr. Flowers’s lawyer concluded her argument, Justice Clarence Thomas asked his first questions from the bench since 2016. He wanted to know whether the defense lawyer in the sixth trial had excluded any jurors. The lawyer said yes.

“And what was the race of the jurors struck there?” Justice Thomas asked.

White, said the lawyer, Sheri Lynn Johnson.

Justice Thomas holds the modern record for silence on the bench. Before his questions in 2016, he had gone a decade without asking one. His explanations have varied, but he has said lately that the other justices asked so many questions that they were rude to the lawyers before them.

The balance of the argument went well for Mr. Flowers, whose case has attracted widespread attention. Justices across the ideological spectrum said the track record of the prosecutor, Doug Evans, was deeply troubling. Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. called it “unusual and really disturbing.”

In the first four trials, held between 1997 and 2007, Mr. Evans used all 36 of his peremptory challenges — ones that do not require giving a reason — to strike black jurors from serving. Three of those trials ended in convictions reversed on appeal, and one in a mistrial.

Official court records do not show the racial makeup of the jury pool for the fifth trial, in 2008, but the jury itself included nine white and three black people. It deadlocked, and the judge declared mistrial.

Over the years, Mississippi courts twice ruled that Mr. Evans had violated Batson v. Kentucky, a 1986 decision that made an exception to the centuries-old rule that peremptory challenges are completely discretionary and cannot be second-guessed.

In the Batson case, the court ruled that racial discrimination in jury selection was different, and it required lawyers accused of it to provide a nondiscriminatory explanation.

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, who wrote an article in The Yale Law Journal calling for vigorous enforcement of the Batson decision when he was a law student, said that Mr. Evans’s track record in the case mattered in the Supreme Court’s assessment of the sixth trial, which took place in 2010.

“We can’t take the history out of the case,” he said.

Even the state’s lawyer, Jason Davis, said that “the history in this case is troubling.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. asked whether the court was entitled to take account of that history, and Mr. Davis said it could.

But he added that Mr. Evans had offered “valid race-neutral reasons for each strike” in the sixth trial.

At that trial, Mr. Evans accepted the first black prospective juror and struck the next five. Mr. Evans questioned black prospective jurors closely, asking an average of 29 questions of each of them. He asked the 11 white jurors who were eventually seated an average of one question each.

In that disparity, Justice Elena Kagan said, “the numbers themselves are staggering.”

Justices Alito and Sonia Sotomayor both suggested that Mr. Evans should have been taken off the case long ago.

“Could the attorney general have said, you know, enough already, we’re going to send one of our own people?” Justice Alito asked Mr. Davis, the state’s lawyer.

Under Mississippi law, Mr. Davis replied, state officials can step in only when requested by local ones like Mr. Evans, and there was no such request in the Flowers case. “So that was not an option in this case,” he said.

Much of the argument delved into Mr. Evans’s stated reasons for striking jurors in the sixth trial.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer described the characteristics of two potential jurors, one black and one white. Both were women in their mid-40s who had completed some college, strongly favored the death penalty and had some professional interactions with members of Mr. Flowers’s family. Justice Breyer suggested that race had been the decisive factor.

Justice Elena Kagan seemed to agree, noting that the black potential juror had an uncle who worked as a prison guard and a relative who had been victim of a violent crime. “Except for her race,” Justice Kagan said, “you would think that this is a juror that a prosecutor would love when she walks in the door.”

The justices had varied responses to whether the reasons offered by Mr. Evans appeared to be pretexts for racial discrimination. But there was something like a consensus that Mr. Evans’s past conduct tipped the balance in Mr. Flowers’s favor.

Mr. Flowers’s case was the subject of season-long examination by the podcast “In the Dark,” which raised substantial questions about his guilt. In February, the podcast won a George Polk award, a prestigious journalism prize, for its work about the case.

While the Supreme Court seemed likely to rule that the jury selection in Mr. Flowers’s latest trial was marred by unconstitutional racial discrimination, setting up the possibility of a seventh trial, its ruling is unlikely to establish any fresh legal principles.

Justice Kavanaugh said the key principle in the Batson decision was sufficient to address the matter. “You can’t just assume that someone’s going to be favorable to someone because they share the same race,” he said.

“Part of Batson was about confidence of the community and the fairness of the criminal justice system,” he said. “And that was against a backdrop of a lot of decades of all-white juries convicting black defendants.”

When Justice Thomas spoke near the end of the argument, it jolted the courtroom. His three questions suggested that both sides rely on racial stereotypes in picking jurors.

Justice Sotomayor responded that, with one exception, the defense lawyer could not have stricken any potential black jurors because Mr. Evans had already excluded them all.

Justice Thomas has offered shifting reasons for his silence during Supreme Court arguments. In his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” he wrote that he had never asked questions in college or law school and that he had been intimidated by some of his fellow students.

He has also said he was self-conscious about the way he spoke, partly because he had been teased about the accent he grew up with in Georgia. But in recent years, he has mostly said that he did not ask questions out of simple courtesy.

On the last two occasions on which he asked questions, in 2016 and on Wednesday, Justice Thomas asked questions only after the last lawyer finished early and was about to sit down.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Mississippi Man Tried

Six Times for the Same Crime

May 20, 2018 | by David Leonhardt | https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/20/opinion/mississippi-curtis-flowers-trial.html

Curtis Flowers, left, leaving the Montgomery County Courthouse in Winona, Miss.

One morning nearly 22 years ago, four employees of a furniture store in a small Mississippi town were shot to death. For months afterward, local law-enforcement seemed stumped by the crime. Eventually, the top prosecutor — Doug Evans — charged a former store employee, Curtis Flowers, a black man who had no criminal record.

The case since then has been unlike any other I’ve ever heard of. Evans has put Flowers on trial six separate times — even though no gun, fingerprints or other physical evidence ties Flowers to the crime and no witness even puts him at the store that day.

At each of the first three trials, Flowers was convicted, but the Mississippi Supreme Court threw out all three convictions. The first two times, it cited misconduct by Evans during the trial, and the third time it found that Evans had kept African-Americans off the jury. The justices called it as bad a case of such racial discrimination “as we have ever seen.”

The fourth trial was the first to have more than one black juror, and it ended with a hung jury. The fifth also had multiple black jurors and likewise ended in a mistrial. The sixth trial had only one black juror, and Flowers was convicted, thanks largely to dubious circumstantial testimony that Evans had coached witnesses to give. I see no good reason to believe that Curtis Flowers is guilty.

Yet today he sits in solitary confinement, on death row, in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison. He is serving his 22nd straight year behind bars, having never been released between convictions. He will turn 48 years old next week. His parents continue to visit him as often as possible.

A death row cell at the Mississippi State Prison in Parchman.

His heartbreaking, enraging story is the subject of a new podcast — the second season of “In the Dark,” led by Madeleine Baran of American Public Media — that’s already been downloaded more than two million times. The reporting and storytelling are fantastic, and I can’t capture all of it here. If you aren’t already listening to the podcast, I recommend it.

While the Flowers case is shocking in its details, it is all too typical in its broad strokes: The United States suffers from a crisis of unjust imprisonment. The crisis has been caused partly by powerful, unaccountable prosecutors, like Doug Evans. And the costs are borne overwhelmingly by black men, like Flowers.

Racist prosecutor Doug Evans, center, interviewing a witness in the sixth trial of Curtis Flowers.

We now know that dozens of innocent people have been executed in recent decades. Many others languish behind bars. My colleague Nicholas Kristof, in his latest column, told the story of Kevin Cooper, who’s on death row in California because of highly questionable evidence. Cases like these are the most extreme part of our mass-incarceration problem. As the legal scholar Michelle Alexander has noted, a larger share of black Americans are imprisoned than black South Africans were during apartheid. “A human rights nightmare is occurring on our watch,” she has written.

When Americans today look back on the past, many of us wonder how our ancestors could have tolerated blatant injustices — like child labor, Jim Crow or male-only voting — for so long. When future generations look back on our era, I expect they will ask a similar question. They will be outraged that we forcibly confined a couple million of our fellow human beings to cages, often for no good reason.

President Trump and his attorney general, Jeff Sessions, are trying to make the problem even worse, by locking up ever more people. But Trump and Sessions can’t squelch the burgeoning, bipartisan movement for criminal-justice reform. They can’t, because as the recent Pulitzer-winning author James Forman Jr. points out, criminal justice happens mostly at the local and state levels. “We should always remember that the fight is going to be at the local level,” Forman told NPR’s Terry Gross, “and, there, we continue to win.”

To take one example, manufactured jailhouse confessions are a common part of wrongful prosecutions (and are central to the Flowers case). With a shocking frequency, prosecutors and police coax so-called snitches to lie outright about what other prisoners say. In response, Texas enacted a law last year requiring the tracking of snitches and the disclosure of any plea deals to defense attorneys, who can then call the testimony into question in front of a jury. Rebecca Brown of the Innocence Project told me that the Texas law was “excellent” — and that the Illinois legislature had passed an even better version, awaiting the governor’s signature.

Elsewhere, some district attorneys are trying to make the system fairer on their own. It’s happening in Brooklyn, Chicago, Philadelphia and other cities. Most prosecutors, after all, are decent, ethical public servants. One change involves “open-file” policies, which give the defense attorney access to all of the evidence in a case. That may seem like an obvious step, and it’s the norm in civil trials. Yet it remains rare in criminal trials.

I don’t want to exaggerate the recent progress. As you read this column, thousands upon thousands of American citizens sit behind bars, unjustly denied their freedom. “Ooooh, I miss Curtis,” his devastated father, Archie Flowers, says on the podcast. “Yes. It is rough. Rough, rough, rough, rough.”

But the Flowers family refuses to give up hoping for justice. Curtis Flowers’s sixth conviction is still being appealed, and new evidence — uncovered by the podcast — seems likely to help that appeal.

If the Flowers family won’t give in to despair, nobody else should, either.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Clarence Thomas Breaks a Three-Year Silence at Supreme Court Hearing On Curtis Flowers

March 21, 2019 | by Adam Liptak | https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/us/politics/clarence-thomas-speaks-supreme-court.html

WASHINGTON — For the first 55 minutes of a Supreme Court argument on Wednesday about racial discrimination in jury selection, the justices seemed united in their view that a white Mississippi prosecutor had violated the Constitution in his determined efforts to exclude black jurors from the six trials of Curtis Flowers, who was convicted of murdering four people in a furniture store.

As Mr. Flowers’s lawyer concluded her argument, Justice Clarence Thomas asked his first questions from the bench since 2016. He wanted to know whether the defense lawyer in the sixth trial had excluded any jurors. The lawyer said yes.

“And what was the race of the jurors struck there?” Justice Thomas asked.

White, said the lawyer, Sheri Lynn Johnson.

Justice Thomas holds the modern record for silence on the bench. Before his questions in 2016, he had gone a decade without asking one. His explanations have varied, but he has said lately that the other justices asked so many questions that they were rude to the lawyers before them.

The balance of the argument went well for Mr. Flowers, whose case has attracted widespread attention. Justices across the ideological spectrum said the track record of the prosecutor, Doug Evans, was deeply troubling. Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. called it “unusual and really disturbing.”

In the first four trials, held between 1997 and 2007, Mr. Evans used all 36 of his peremptory challenges — ones that do not require giving a reason — to strike black jurors from serving. Three of those trials ended in convictions reversed on appeal, and one in a mistrial.

Official court records do not show the racial makeup of the jury pool for the fifth trial, in 2008, but the jury itself included nine white and three black people. It deadlocked, and the judge declared mistrial.

Over the years, Mississippi courts twice ruled that Mr. Evans had violated Batson v. Kentucky, a 1986 decision that made an exception to the centuries-old rule that peremptory challenges are completely discretionary and cannot be second-guessed.

In the Batson case, the court ruled that racial discrimination in jury selection was different, and it required lawyers accused of it to provide a nondiscriminatory explanation.

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, who wrote an article in The Yale Law Journal calling for vigorous enforcement of the Batson decision when he was a law student, said that Mr. Evans’s track record in the case mattered in the Supreme Court’s assessment of the sixth trial, which took place in 2010.

“We can’t take the history out of the case,” he said.

Even the state’s lawyer, Jason Davis, said that “the history in this case is troubling.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. asked whether the court was entitled to take account of that history, and Mr. Davis said it could.

But he added that Mr. Evans had offered “valid race-neutral reasons for each strike” in the sixth trial.

At that trial, Mr. Evans accepted the first black prospective juror and struck the next five. Mr. Evans questioned black prospective jurors closely, asking an average of 29 questions of each of them. He asked the 11 white jurors who were eventually seated an average of one question each.

In that disparity, Justice Elena Kagan said, “the numbers themselves are staggering.”

Justices Alito and Sonia Sotomayor both suggested that Mr. Evans should have been taken off the case long ago.

“Could the attorney general have said, you know, enough already, we’re going to send one of our own people?” Justice Alito asked Mr. Davis, the state’s lawyer.

Under Mississippi law, Mr. Davis replied, state officials can step in only when requested by local ones like Mr. Evans, and there was no such request in the Flowers case. “So that was not an option in this case,” he said.

Much of the argument delved into Mr. Evans’s stated reasons for striking jurors in the sixth trial.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer described the characteristics of two potential jurors, one black and one white. Both were women in their mid-40s who had completed some college, strongly favored the death penalty and had some professional interactions with members of Mr. Flowers’s family. Justice Breyer suggested that race had been the decisive factor.

Justice Elena Kagan seemed to agree, noting that the black potential juror had an uncle who worked as a prison guard and a relative who had been victim of a violent crime. “Except for her race,” Justice Kagan said, “you would think that this is a juror that a prosecutor would love when she walks in the door.”

The justices had varied responses to whether the reasons offered by Mr. Evans appeared to be pretexts for racial discrimination. But there was something like a consensus that Mr. Evans’s past conduct tipped the balance in Mr. Flowers’s favor.

Mr. Flowers’s case was the subject of season-long examination by the podcast “In the Dark,” which raised substantial questions about his guilt. In February, the podcast won a George Polk award, a prestigious journalism prize, for its work about the case.

While the Supreme Court seemed likely to rule that the jury selection in Mr. Flowers’s latest trial was marred by unconstitutional racial discrimination, setting up the possibility of a seventh trial, its ruling is unlikely to establish any fresh legal principles.

Justice Kavanaugh said the key principle in the Batson decision was sufficient to address the matter. “You can’t just assume that someone’s going to be favorable to someone because they share the same race,” he said.

“Part of Batson was about confidence of the community and the fairness of the criminal justice system,” he said. “And that was against a backdrop of a lot of decades of all-white juries convicting black defendants.”

When Justice Thomas spoke near the end of the argument, it jolted the courtroom. His three questions suggested that both sides rely on racial stereotypes in picking jurors.

Justice Sotomayor responded that, with one exception, the defense lawyer could not have stricken any potential black jurors because Mr. Evans had already excluded them all.

Justice Thomas has offered shifting reasons for his silence during Supreme Court arguments. In his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” he wrote that he had never asked questions in college or law school and that he had been intimidated by some of his fellow students.

He has also said he was self-conscious about the way he spoke, partly because he had been teased about the accent he grew up with in Georgia. But in recent years, he has mostly said that he did not ask questions out of simple courtesy.

On the last two occasions on which he asked questions, in 2016 and on Wednesday, Justice Thomas asked questions only after the last lawyer finished early and was about to sit down.