CORONAVIRUS

Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate

No, the coronavirus is not an “equalizer.”

Black people are being infected and dying at higher rates.

Here’s what Milwaukee is doing about it — and why governments need to start releasing data on the race of COVID-19 patients.

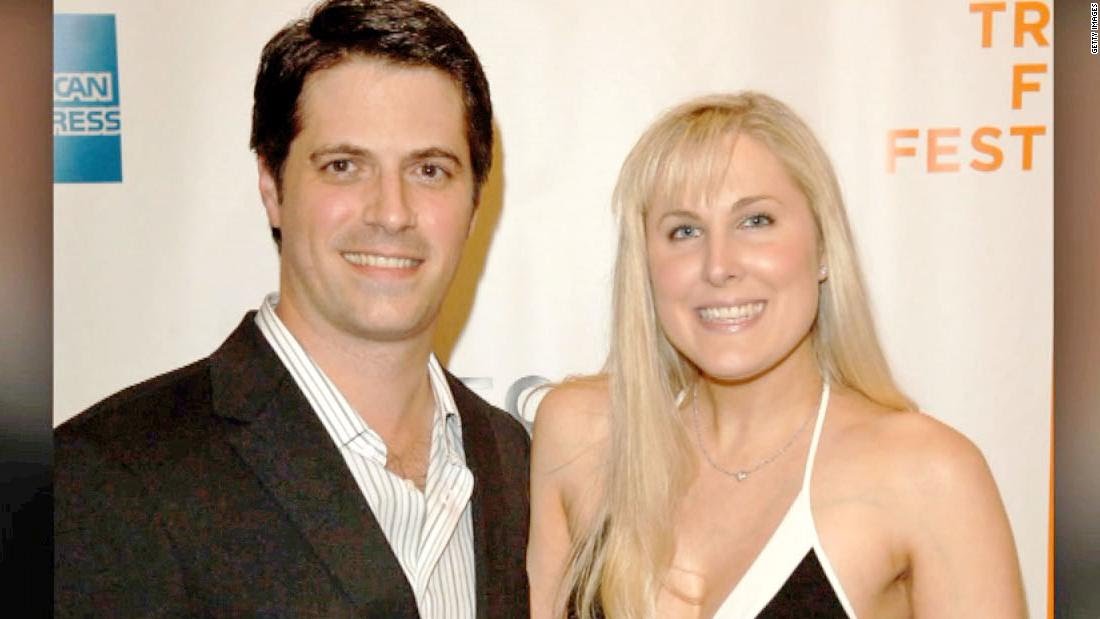

Fred Royal, the Milwaukee head of the NAACP, walks empty

streets near his home in a largely black neighborhood hit

hard by the coronavirus. He knows three people who have

died. (Darren Hauck for ProPublica)

ProPublica

by Akilah Johnson

and Talia Buford

April 3, 2020

The coronavirus entered Milwaukee from a white, affluent suburb. Then it took root in the city’s black community and erupted.

As public health officials watched cases rise in March, too many in the community shrugged off warnings. Rumors and conspiracy theories proliferated on social media, pushing the bogus idea that black people are somehow immune to the disease. And much of the initial focus was on international travel, so those who knew no one returning from Asia or Europe were quick to dismiss the risk.

Then, when the shelter-in-place order came, there was a natural pushback among those who recalled other painful government restrictions — including segregation and mass incarceration — on where black people could walk and gather.

“We’re like, ‘We have to wake people up,’” said Milwaukee Health Commissioner Jeanette Kowalik.

As the disease spread at a higher rate in the black community, it made an even deeper cut. Environmental, economic and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes. In Milwaukee, simply being black means your life expectancy is 14 years shorter, on average, than someone white.

As of Friday morning, African Americans made up almost half of Milwaukee County’s 945 cases and 81% of its 27 deaths in a county whose population is 26% black. Milwaukee is one of the few places in the United States that is tracking the racial breakdown of people who have been infected by the novel coronavirus, offering a glimpse at the disproportionate destruction it is inflicting on black communities nationwide.

In Michigan, where the state’s population is 14% black, African Americans made up 35% of cases and 40% of deaths as of Friday morning. Detroit, where a majority of residents are black, has emerged as a hot spot with a high death toll. As has New Orleans. Louisiana has not published case breakdowns by race, but 40% of the state’s deaths have happened in Orleans Parish, where the majority of residents are black.

Illinois and North Carolina are two of the few areas publishing statistics on COVID-19 cases by race, and their data shows a disproportionate number of African Americans were infected.

“It will be unimaginable pretty soon,” said Dr. Celia J. Maxwell, an infectious disease physician and associate dean at Howard University College of Medicine, a school and hospital in Washington dedicated to the education and care of the black community. “And anything that comes around is going to be worse in our patients. Period. Many of our patients have so many problems, but this is kind of like the nail in the coffin.”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks virulent outbreaks and typically releases detailed data that includes information about the age, race and location of the people affected. For the coronavirus pandemic, the CDC has released location and age data, but it has been silent on race. The CDC did not respond to ProPublica’s request for race data related to the coronavirus or answer questions about whether they were collecting it at all.

Experts say that the nation’s unwillingness to publicly track the virus by race could obscure a crucial underlying reality: It’s quite likely that a disproportionate number of those who die of coronavirus will be black.

The reasons for this are the same reasons that African Americans have disproportionately high rates of maternal death, low levels of access to medical care and higher rates of asthma, said Dr. Camara Jones, a family physician, epidemiologist and visiting fellow at Harvard University.

“COVID is just unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustices and the impact of residential segregation,” said Jones, who spent 13 years at the CDC, focused on identifying, measuring and addressing racial bias within the medical system. “This is the time to name racism as the cause of all of those things. The overrepresentation of people of color in poverty and white people in wealth is not just a happenstance. … It’s because we’re not valued.”

Five congressional Democrats wrote to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, whose department encompasses the CDC, last week demanding the federal government collect and release the breakdown of coronavirus cases by race and ethnicity.

Without demographic data, the members of Congress wrote, health officials and lawmakers won’t be able to address inequities in health outcomes and testing that may emerge: “We urge you not to delay collecting this vital information, and to take any additional necessary steps to ensure that all Americans have the access they need to COVID-19 testing and treatment.”

The city’s health officials have tried to take a purposeful

approach to communicate information. (Darren Hauck for ProPublica)

Milwaukee, one of the few places already tracking coronavirus cases and deaths by race, provides an early indication of what would surface nationally if the federal government actually did this, or locally if other cities and states took its lead.

Milwaukee, both the city and county, passed resolutions last summer that were seen as important steps in addressing decades of race-based inequality.

“We declared racism as a public health issue,” said Kowalik, the city’s health commissioner. “It frames not only how we do our work but how transparent we are about how things are going. It impacts how we manage an outbreak.”

Milwaukee is trying to be purposeful in how it communicates information about the best way to slow the pandemic. It is addressing economic and logistical roadblocks that stand in the way of safety. And it’s being transparent about who is infected, who is dying and how the virus spread in the first place.

Kowalik described watching the virus spread into the city, without enough information, because of limited testing, to be able to take early action to contain it.

At the beginning of March, Wisconsin had one case. State public health officials still considered the risk from the coronavirus “low.” Testing criteria was extremely strict, as it was in many places across the country: You had to have symptoms and have traveled to China, Iran, South Korea or Italy within 14 days or have had contact with someone who had a confirmed case of COVID-19.

So, she said, she waited, wondering: “When are we going to be able to test for this to see if it is in our community?”

About two weeks later, Milwaukee had its first case.

The city’s patient zero had been in contact with a person from a neighboring, predominately white and affluent suburb who had tested positive. Given how much commuting occurs in and out of Milwaukee, with some making a 180-mile round trip to Chicago, Kowalik said she knew it would only be a matter of time before the virus spread into the city.

A day later came the city’s second case, someone who contracted the virus while in Atlanta. Kowalik said she started questioning the rigidness of the testing guidelines. Why didn’t they include domestic travel?

By the fourth case, she said, “we determined community spread. … It happened so quickly.”

Within the span of a week, Milwaukee went from having one case to nearly 40. Most of the sick people were middle-aged, African American men. By week two, the city had over 350 cases. And now, there are more than 945 cases countywide, with the bulk in the city of Milwaukee, where the population is 39% black. People of all ages have contracted the virus and about half are African American.

The county’s online dashboard of coronavirus cases keeps up-to-date information on the racial breakdown of those who have tested positive. As of Thursday morning, 19 people had died of illness related to COVID-19 in Milwaukee County. All but four were black, according to the county medical examiner’s office. Records show that at least 11 of the deceased had diabetes, eight had hypertension and 15 had a mixture of chronic health conditions that included heart and lung disease.

Because of discrimination and generational income inequality, black households in the county earned only 50% as much as white ones in 2018, according to census statistics. Black people are far less likely to own homes than white people in Milwaukee and far more likely to rent, putting black renters at the mercy of landlords who can kick them out if they can’t pay during an economic crisis, at the same time as people are being told to stay home. And when it comes to health insurance, black people are more likely to be uninsured than their white counterparts.

African Americans have gravitated to jobs in sectors viewed as reliable paths to the middle class — health care, transportation, government, food supply — which are now deemed “essential,” rendering them unable to stay home. In places like New York City, the virus’ epicenter, black people are among the only ones still riding the subway.

“And let’s be clear, this is not because people want to live in those conditions,” said Gordon Francis Goodwin, who works for Government Alliance on Race and Equity, a national racial equity organization that worked with Milwaukee on its health and equity framework. “This is a matter of taking a look at how our history kept people from actually being fully included.”

Fred Royal, head of the Milwaukee branch of the NAACP, knows three people who have died from the virus, including 69-year-old Lenard Wells, a former Milwaukee police lieutenant and a mentor to others in the black community. Royal’s 38-year-old cousin died from the virus last week in Atlanta. His body was returned home Tuesday.

Royal is hearing that people aren’t necessarily being hospitalized but are being sent home instead and “told to self-medicate.”

“What is alarming about that,” he said, “is that a number of those individuals were sent home with symptoms and died before the confirmation of their test came back.”

Royal has spent the past days coordinating with front-line

community groups trying to make sure residents have what

they need in order to stay inside. (Darren Hauck for ProPublica)

Health Commissioner Kowalik said that there have been delays of up to two weeks in getting results back from some private labs, but nearly all of those who died have done so at hospitals or while in hospice. Still, Kowalik said she understood why some members in the black community distrusted the care they might receive in a hospital.

In January, a 25-year-old day care teacher named Tashonna Ward died after staff at Froedtert Hospital failed to check her vital signs. Federal officials examined 20 patient records and found seven patients, including Ward, didn’t receive proper care. The report didn’t reveal the race of those whose records it examined at the hospital, which predominantly serves black patients. Froedtert Hospital declined to speak to issues raised in the report, according to a February article from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and it had not submitted any corrective actions to federal officials.

“What black folks are accustomed to in Milwaukee and anywhere in the country, really, is pain not being acknowledged and constant inequities that happen in health care delivery,” Kowalik said.

The health commissioner herself, a black woman who grew up in Milwaukee, said she’s all too familiar with the city’s enduring struggles with segregation and racism. Her mother is black and her father Polish, and she remembers the stories they shared about trying to buy a house as a young interracial couple in Sherman Park, a neighborhood once off-limits to blacks.

“My father couldn’t get a mortgage for the house. He had to go to the bank without my mom,” Kowalik said.

It is the same neighborhood where fury and frustration sparked protests that, at times, roiled into riots in 2016 when a Milwaukee police officer fatally shot Sylville Smith, a 23-year-old black man.

And it is the same neighborhood that has a concentration of poor health outcomes when you overlay a heat map of conditions, be it lead poisoning, infant mortality — and now, she said, COVID-19.

Knowing which communities are most impacted allows public health officials to tailor their messaging to overcome the distrust of black residents.

“We’ve been told so much misinformation over the years about the condition of our community,” Royal, of the NAACP, said. “I believe a lot of people don’t trust what the government says.”

Kowalik has met — virtually — with trusted and influential community leaders to discuss outreach efforts to ensure everyone is on the same page about the importance of staying home and keeping 6 feet away from others if they must go out.

Police and inspectors are responding to complaints received about “noncompliant” businesses forcing staff to come to work or not practicing social distancing in the workplace. Violators could face fines.

“Who are we getting these complaints from?” she asked. “Many people of color.”

Residents have been urged to call 211 if they need help with anything from finding something to eat or a place to stay. And the state has set up two voluntary isolation facilities for people with COVID-19 symptoms whose living situations are untenable, including a Super 8 motel in Milwaukee.

Despite the work being done in Milwaukee, experts like Linda Sprague Martinez, a community health researcher at Boston University’s School of Social Work, worry that the government is not paying close enough attention to race, and as the disease spreads, will do too little to blunt its toll.

“When COVID-19 passes and we see the losses … it will be deeply tied to the story of post-World War II policies that left communities marginalized,” Sprague said. “Its impact is going to be tied to our history and legacy of racial inequities. It’s going to be tied to the fact that we live in two very different worlds.”

Update, April 3, 2020: This story has been updated to reflect that Illinois and North Carolina are breaking coronavirus cases down by race.

Doris Burke and Hannah Fresques contributed reporting.

www.propublica.org

www.propublica.org

.

Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate

No, the coronavirus is not an “equalizer.”

Black people are being infected and dying at higher rates.

Here’s what Milwaukee is doing about it — and why governments need to start releasing data on the race of COVID-19 patients.

Fred Royal, the Milwaukee head of the NAACP, walks empty

streets near his home in a largely black neighborhood hit

hard by the coronavirus. He knows three people who have

died. (Darren Hauck for ProPublica)

ProPublica

by Akilah Johnson

and Talia Buford

April 3, 2020

The coronavirus entered Milwaukee from a white, affluent suburb. Then it took root in the city’s black community and erupted.

As public health officials watched cases rise in March, too many in the community shrugged off warnings. Rumors and conspiracy theories proliferated on social media, pushing the bogus idea that black people are somehow immune to the disease. And much of the initial focus was on international travel, so those who knew no one returning from Asia or Europe were quick to dismiss the risk.

Then, when the shelter-in-place order came, there was a natural pushback among those who recalled other painful government restrictions — including segregation and mass incarceration — on where black people could walk and gather.

“We’re like, ‘We have to wake people up,’” said Milwaukee Health Commissioner Jeanette Kowalik.

As the disease spread at a higher rate in the black community, it made an even deeper cut. Environmental, economic and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes. In Milwaukee, simply being black means your life expectancy is 14 years shorter, on average, than someone white.

As of Friday morning, African Americans made up almost half of Milwaukee County’s 945 cases and 81% of its 27 deaths in a county whose population is 26% black. Milwaukee is one of the few places in the United States that is tracking the racial breakdown of people who have been infected by the novel coronavirus, offering a glimpse at the disproportionate destruction it is inflicting on black communities nationwide.

In Michigan, where the state’s population is 14% black, African Americans made up 35% of cases and 40% of deaths as of Friday morning. Detroit, where a majority of residents are black, has emerged as a hot spot with a high death toll. As has New Orleans. Louisiana has not published case breakdowns by race, but 40% of the state’s deaths have happened in Orleans Parish, where the majority of residents are black.

Illinois and North Carolina are two of the few areas publishing statistics on COVID-19 cases by race, and their data shows a disproportionate number of African Americans were infected.

“It will be unimaginable pretty soon,” said Dr. Celia J. Maxwell, an infectious disease physician and associate dean at Howard University College of Medicine, a school and hospital in Washington dedicated to the education and care of the black community. “And anything that comes around is going to be worse in our patients. Period. Many of our patients have so many problems, but this is kind of like the nail in the coffin.”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks virulent outbreaks and typically releases detailed data that includes information about the age, race and location of the people affected. For the coronavirus pandemic, the CDC has released location and age data, but it has been silent on race. The CDC did not respond to ProPublica’s request for race data related to the coronavirus or answer questions about whether they were collecting it at all.

Experts say that the nation’s unwillingness to publicly track the virus by race could obscure a crucial underlying reality: It’s quite likely that a disproportionate number of those who die of coronavirus will be black.

The reasons for this are the same reasons that African Americans have disproportionately high rates of maternal death, low levels of access to medical care and higher rates of asthma, said Dr. Camara Jones, a family physician, epidemiologist and visiting fellow at Harvard University.

“COVID is just unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustices and the impact of residential segregation,” said Jones, who spent 13 years at the CDC, focused on identifying, measuring and addressing racial bias within the medical system. “This is the time to name racism as the cause of all of those things. The overrepresentation of people of color in poverty and white people in wealth is not just a happenstance. … It’s because we’re not valued.”

Five congressional Democrats wrote to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, whose department encompasses the CDC, last week demanding the federal government collect and release the breakdown of coronavirus cases by race and ethnicity.

Without demographic data, the members of Congress wrote, health officials and lawmakers won’t be able to address inequities in health outcomes and testing that may emerge: “We urge you not to delay collecting this vital information, and to take any additional necessary steps to ensure that all Americans have the access they need to COVID-19 testing and treatment.”

The city’s health officials have tried to take a purposeful

approach to communicate information. (Darren Hauck for ProPublica)

Milwaukee, one of the few places already tracking coronavirus cases and deaths by race, provides an early indication of what would surface nationally if the federal government actually did this, or locally if other cities and states took its lead.

Milwaukee, both the city and county, passed resolutions last summer that were seen as important steps in addressing decades of race-based inequality.

“We declared racism as a public health issue,” said Kowalik, the city’s health commissioner. “It frames not only how we do our work but how transparent we are about how things are going. It impacts how we manage an outbreak.”

Milwaukee is trying to be purposeful in how it communicates information about the best way to slow the pandemic. It is addressing economic and logistical roadblocks that stand in the way of safety. And it’s being transparent about who is infected, who is dying and how the virus spread in the first place.

Kowalik described watching the virus spread into the city, without enough information, because of limited testing, to be able to take early action to contain it.

At the beginning of March, Wisconsin had one case. State public health officials still considered the risk from the coronavirus “low.” Testing criteria was extremely strict, as it was in many places across the country: You had to have symptoms and have traveled to China, Iran, South Korea or Italy within 14 days or have had contact with someone who had a confirmed case of COVID-19.

So, she said, she waited, wondering: “When are we going to be able to test for this to see if it is in our community?”

About two weeks later, Milwaukee had its first case.

The city’s patient zero had been in contact with a person from a neighboring, predominately white and affluent suburb who had tested positive. Given how much commuting occurs in and out of Milwaukee, with some making a 180-mile round trip to Chicago, Kowalik said she knew it would only be a matter of time before the virus spread into the city.

A day later came the city’s second case, someone who contracted the virus while in Atlanta. Kowalik said she started questioning the rigidness of the testing guidelines. Why didn’t they include domestic travel?

By the fourth case, she said, “we determined community spread. … It happened so quickly.”

Within the span of a week, Milwaukee went from having one case to nearly 40. Most of the sick people were middle-aged, African American men. By week two, the city had over 350 cases. And now, there are more than 945 cases countywide, with the bulk in the city of Milwaukee, where the population is 39% black. People of all ages have contracted the virus and about half are African American.

The county’s online dashboard of coronavirus cases keeps up-to-date information on the racial breakdown of those who have tested positive. As of Thursday morning, 19 people had died of illness related to COVID-19 in Milwaukee County. All but four were black, according to the county medical examiner’s office. Records show that at least 11 of the deceased had diabetes, eight had hypertension and 15 had a mixture of chronic health conditions that included heart and lung disease.

Because of discrimination and generational income inequality, black households in the county earned only 50% as much as white ones in 2018, according to census statistics. Black people are far less likely to own homes than white people in Milwaukee and far more likely to rent, putting black renters at the mercy of landlords who can kick them out if they can’t pay during an economic crisis, at the same time as people are being told to stay home. And when it comes to health insurance, black people are more likely to be uninsured than their white counterparts.

African Americans have gravitated to jobs in sectors viewed as reliable paths to the middle class — health care, transportation, government, food supply — which are now deemed “essential,” rendering them unable to stay home. In places like New York City, the virus’ epicenter, black people are among the only ones still riding the subway.

“And let’s be clear, this is not because people want to live in those conditions,” said Gordon Francis Goodwin, who works for Government Alliance on Race and Equity, a national racial equity organization that worked with Milwaukee on its health and equity framework. “This is a matter of taking a look at how our history kept people from actually being fully included.”

Fred Royal, head of the Milwaukee branch of the NAACP, knows three people who have died from the virus, including 69-year-old Lenard Wells, a former Milwaukee police lieutenant and a mentor to others in the black community. Royal’s 38-year-old cousin died from the virus last week in Atlanta. His body was returned home Tuesday.

Royal is hearing that people aren’t necessarily being hospitalized but are being sent home instead and “told to self-medicate.”

“What is alarming about that,” he said, “is that a number of those individuals were sent home with symptoms and died before the confirmation of their test came back.”

Royal has spent the past days coordinating with front-line

community groups trying to make sure residents have what

they need in order to stay inside. (Darren Hauck for ProPublica)

Health Commissioner Kowalik said that there have been delays of up to two weeks in getting results back from some private labs, but nearly all of those who died have done so at hospitals or while in hospice. Still, Kowalik said she understood why some members in the black community distrusted the care they might receive in a hospital.

In January, a 25-year-old day care teacher named Tashonna Ward died after staff at Froedtert Hospital failed to check her vital signs. Federal officials examined 20 patient records and found seven patients, including Ward, didn’t receive proper care. The report didn’t reveal the race of those whose records it examined at the hospital, which predominantly serves black patients. Froedtert Hospital declined to speak to issues raised in the report, according to a February article from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and it had not submitted any corrective actions to federal officials.

“What black folks are accustomed to in Milwaukee and anywhere in the country, really, is pain not being acknowledged and constant inequities that happen in health care delivery,” Kowalik said.

The health commissioner herself, a black woman who grew up in Milwaukee, said she’s all too familiar with the city’s enduring struggles with segregation and racism. Her mother is black and her father Polish, and she remembers the stories they shared about trying to buy a house as a young interracial couple in Sherman Park, a neighborhood once off-limits to blacks.

“My father couldn’t get a mortgage for the house. He had to go to the bank without my mom,” Kowalik said.

It is the same neighborhood where fury and frustration sparked protests that, at times, roiled into riots in 2016 when a Milwaukee police officer fatally shot Sylville Smith, a 23-year-old black man.

And it is the same neighborhood that has a concentration of poor health outcomes when you overlay a heat map of conditions, be it lead poisoning, infant mortality — and now, she said, COVID-19.

Knowing which communities are most impacted allows public health officials to tailor their messaging to overcome the distrust of black residents.

“We’ve been told so much misinformation over the years about the condition of our community,” Royal, of the NAACP, said. “I believe a lot of people don’t trust what the government says.”

Kowalik has met — virtually — with trusted and influential community leaders to discuss outreach efforts to ensure everyone is on the same page about the importance of staying home and keeping 6 feet away from others if they must go out.

Police and inspectors are responding to complaints received about “noncompliant” businesses forcing staff to come to work or not practicing social distancing in the workplace. Violators could face fines.

“Who are we getting these complaints from?” she asked. “Many people of color.”

Residents have been urged to call 211 if they need help with anything from finding something to eat or a place to stay. And the state has set up two voluntary isolation facilities for people with COVID-19 symptoms whose living situations are untenable, including a Super 8 motel in Milwaukee.

Despite the work being done in Milwaukee, experts like Linda Sprague Martinez, a community health researcher at Boston University’s School of Social Work, worry that the government is not paying close enough attention to race, and as the disease spreads, will do too little to blunt its toll.

“When COVID-19 passes and we see the losses … it will be deeply tied to the story of post-World War II policies that left communities marginalized,” Sprague said. “Its impact is going to be tied to our history and legacy of racial inequities. It’s going to be tied to the fact that we live in two very different worlds.”

Update, April 3, 2020: This story has been updated to reflect that Illinois and North Carolina are breaking coronavirus cases down by race.

Doris Burke and Hannah Fresques contributed reporting.

Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate

No, the coronavirus is not an “equalizer.” Black people are being infected and dying at higher rates. Here’s what Milwaukee is doing about it — and why governments need to start releasing data on the race of COVID-19 patients.

.