THE AMERICAN SLAVE COAST

For the very, very, very, very few of you peeps who still read anything longer than 300 words. This book details the $$$$$$ capital accumulation based upon forcibly bred African women in Virginia whose offspring were sold to plantation death camp owners in the deep South. The documentation of this Hell-ocaust was chronicled by a Black man in 1897. This book uses his facts along with historically preserved records to literally recreate for the reader the horrors that African people endured under the complete dehumanization of AmeriKKKa's $$$$$$$ barbaric conscienceless morally deprived chattel slavery. AmeriKKKa's global wealth was created by slavery. Slave breeders & sellers could make cash quicker than the planters who could be wiped out by low prices for their crops or a weather catastrophe. This very rarely discussed part of American history is rarely talked about due to it's horror. Read the first chapter below and download and read the whole book. Send a copy to Kanye West who says Slavery was a choice.

Download whole book epub

CHAPTER ONE

THE AMERICAN SLAVE COAST offers a provocative vision of US history from earliest colonial times through emancipation that presents even the most familiar events and figures in a revealing new light.

Authors Ned and Constance Sublette tell the brutal story of how the slavery industry made the reproductive labor of the people it referred to as “breeding women” essential to the young country’s expansion. Captive African Americans in the slave nation were not only laborers, but merchandise and collateral all at once. in a land without silver, gold, or trustworthy paper money, their children and their children’s children into perpetuity were used as human savings accounts that functioned as the basis of money and credit in a market premised on the continual expansion of slavery. Slaveowners collected interest in the form of newborns, who had a cash value at birth and whose mothers had no legal right to say no to forced mating.

This gripping narrative is driven by the power struggle between the elites of Virginia, the slave-raising “mother of slavery,” and South Carolina, the massive importer of Africans—a conflict that was central to American politics from the making of the Constitution through the debacle of the Confederacy.

Virginia slaveowners won a major victory when Thomas Jefferson’s 1808 prohibition of the African slave trade protected the domestic slave markets for slave-breeding. The interstate slave trade exploded in mississippi during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, drove the US expansion into Texas, and powered attempts to take over Cuba and other parts of Latin America, until a disaffected South Carolina spearheaded the drive to secession and war, pushing the Virginians to secede or lose their slave-breeding industry.

Filled with surprising facts, fascinating incidents, and startling portraits of the people who made, endured, and resisted the slave-breeding industry, The American Slave Coast culminates in the revolutionary Emancipation Proclamation, which at last decommissioned the capitalized womb and armed the African Americans to fight for their freedom.

Introduction

THIS IS A HISTORY of the slave-breeding industry, which we define as the complex of businesses and individuals in the United States who profited from the enslavement of African American children at birth.

At the heart of our account is the intricate connection between the legal fact of people as property—the “chattel principle”—and national expansion. Our narrative doubles, then, as a history of the making of the United States as seen from the point of view of the slave trade.

It also traces the history of money in America. In the Southern United States, the “peculiar institution” of slavery was inextricably associated with its own peculiar economy, interconnected with that of the North.

One of the two principal products of the antebellum slave economy was staple crops, which provided the cash flow—primarily cotton, which was the United States’ major export. The other was enslaved people, who counted as capital and functioned as the stable wealth of the South. African American bodies and childbearing potential collateralized massive amounts of credit, the use of which made slaveowners the wealthiest people in the country. When the Southern states seceded to form the Confederacy they partitioned off, and declared independence for, their economic system in which people were money.

Our chronology reaches from earliest colonial times through emancipation, following the two main phases of the slave trade. The first phase, importation, began with the first known sale of kidnapped Africans in Virginia in 1619 and took place largely, though not entirely, during the colonial years. The second phase, breeding, was the era of the domestic, or interstate, slave trade in African Americans. The key date here—from our perspective, one of the most important dates in American history—was the federal prohibition of the “importation of persons” as of January 1, 1808. After that, the interstate trade was, with minor exceptions, the only slave trade in the United States, and it became massified on a previously impossible scale.

The conflict between North and South is a fundamental trope of American history, but in our narrative, the major conflict is intra-Southern: the commercial antagonism between Virginia, the great slave breeder, and South Carolina, the great slave importer, for control of the market that supplied slave labor to an expanding slavery nation. The dramatic power struggle between the two was central to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 and to secession in 1860–61.

Part One is an overview, intended as an extended introduction to the

subject.

Part Two, which begins the main chronological body of the text, describes the creation of a slave economy during the colonial years.

Part Three centers on the US Constitution’s role as hinge between the two phases of slave importation and slave breeding.

Parts Four through Six cover the years of the slave-breeding industry, from the end of the War of 1812 through emancipation: the rise, peak, and fall of the cotton kingdom.

Note: This book describes an economy in which people were capital, children were interest, and women were routinely violated. We have tried to avoid gratuitously subjecting the reader to offensive language and images, but we are describing a horrifying reality.

The Mother of Slavery

“VIRGINIA WAS THE MOTHER of slavery,” wrote Louis Hughes.

It wasn’t just a figure of speech.

During the fifty-three years from the prohibition of the African slave trade by federal law in 1808 to the debacle of the Confederate States of America in 1861, the Southern economy depended on the functioning of a slave-breeding industry, of which Virginia was the number-one supplier. When Hughes was born in 1832, the market was expanding sharply.

“My father was a white man and my mother a negress,” Hughes wrote.1 That meant he was classified as merchandise at birth, because children inherited the free or enslaved status of the mother, not the father. It had been that way in Virginia for 170 years already when Hughes was born.

Partus sequitur ventrem was the legal term: the status of the newborn follows the status of the womb. Fathers passed inheritances down, mothers passed slavery down. It ensured a steady flow of salable human product from the wombs of women who had no legal right to say no.

Most enslaved African Americans lived and died without writing so much as their names. The Virginia legal code of 1849 provided for “stripes”—flogging—for those who tried to acquire literacy skills. A free person who dared “assemble with negroes for the purpose of instructing them to read or write” could receive a jail sentence of up to six months and a fine of up to a hundred dollars, plus costs.2 An enslaved person who tried to teach others to read might have part of a finger chopped off by the slaveowner, with the full blessing of law.

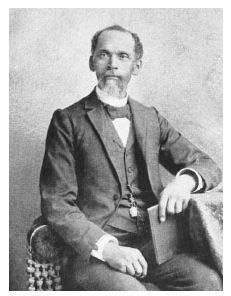

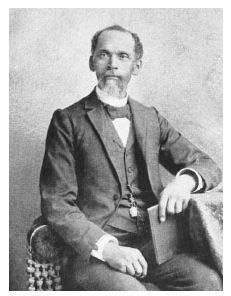

So it was an especially distinguished achievement when in 1897 the sixty-four-year-old Louis Hughes published his memoir, titled Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom: The Institution of Slavery as Seen on the Plantation and in the Home of the Planter. Like the other volumes collectively referred to as slave narratives, it bears witness to a history slaveowners did not want to exist: the firsthand testimony of the enslaved.

By the time Hughes was twelve, he had been sold five times. The third time, he was sold away from his mother to a trader. “It was sad to her to part with me,” he recalled, “though she did not know that she was never to see me again, for my master had said nothing to her regarding his purpose and she only thought, as I did, that I was hired to work on the canal-boat,and that she should see me occasionally. But alas! We never met again.”

Louis Hughes’s author photograph.

The trader carried the boy away from the Charlottesville area that had been his home, down the James River to Richmond. There he was sold a fourth time, to a local man, but Hughes “suffered with chills and fever,” so the dissatisfied purchaser had him resold. This time he went on the auction block, where he was bought by a cotton planter setting up in Pontotoc, Mississippi—a booming region that had recently become available for plantations in the wake of the delivery of large areas of expropriated Chickasaw land into the hands of speculators.

Slaves were designated by geographical origin in the market, with Virginia-and Maryland-born slaves commanding a premium. “It was held by many that [Virginia] had the best slaves,” Hughes wrote. “So when Mr. McGee found I was born and bred in that state he seemed satisfied. The bidding commenced, and I remember well when the auctioneer said: ‘Three hundred eighty dollars—once, twice and sold to Mr. Edward McGee.’”3

McGee had plenty of financing, and he was in a hurry; he bought sixty other people that day.4 A prime field hand would have commanded double or more, but even so, the $380 that bought the sickly twelve-year-old would be more than $10,000 in 2014 money.5

Like the largest number of those forcibly emigrated to the Deep South, McGee’s captives were all made to walk from Virginia to Mississippi, in a coffle.

Southern children grew up seeing coffles approach in a cloud of dust.

A coffle is “a train of men or beasts fastened together,” says the Oxford English Dictionary, and indeed Louis Hughes referred to the coffle he marched in as “a herd.”6 The word comes from the Arabic qafilah, meaning “caravan,” recalling the overland slave trade that existed across the desert from sub-Saharan Africa to the greater Islamic world centuries before Columbus crossed the Atlantic. With the development in the late fifteenth century of the maritime trade that shifted the commercial gravity of Africa southward from the desert to the Atlantic coast, coffles were used to traffic Africans from point of capture in their homeland to point of sale in one of Africa’s many slave ports.

But the people trudging to Mississippi along with Louis Hughes were not Africans. They were African Americans, born into slavery and raised with their eventual sale in mind. Force-marched through wilderness at a pace of twenty or twenty-five miles a day, for five weeks or more, from can’t-see to can’t-see, in blazing sun or cold rain, crossing unbridged rivers, occasionally dropping dead in their tracks, hundreds of thousands of laborers transported themselves down south at gunpoint, where they and all their descendants could expect to be prisoners for life.

Perhaps 80 percent of enslaved children were born to two-parent families—though the mother and father might live on different plantations—but in extant slave-traders’ records of those sold, according to Michael Tadman’s analysis, “complete nuclear families were almost totally absent.” About a quarter of those trafficked southward were children between eight and fifteen, purchased away from their families. The majority of coffle prisoners were male: boys who would never again see their mothers, men who would never again see wives and children.

But there were women and girls in the coffles, too—exposed, as were enslaved women everywhere, to the possibility of sexual violation from their captors. The only age bracket in which females outnumbered males in the trade was twelve to fifteen, when they were as able as the boys to do field labor, and could also bear children.7 Charles Ball, forcibly taken from Maryland to South Carolina in 1805, recalled that The women were merely tied together with a rope, about the size of a bed cord, which was tied like a halter round the neck of each; but the men … were very differently caparisoned. A strong iron collar was closely fitted by means of a padlock round each of our necks. A chain of iron, about a hundred feet in length, was passed through the hasp of each padlock, except at the two ends, where the hasps of the padlocks passed through a link of the chain. In addition to this, we were handcuffed in pairs, with iron staples and bolts, with a short chain, about a foot long, uniting the handcuffs and their wearers in pairs.8

As they tramped along, coffles were typically watched over by whip- and gun-wielding men on horseback and a few dogs, with supply wagons bringing up the rear. In the country coffles slept outdoors on the ground, perhaps in tents; in town they slept in the local jail or in a slave trader’s private jail. Farmers along the route did business with the drivers, selling them quantities of the undernourishing, monotonous fare that enslaved people ate day in and day out.

Sometimes the manacles were taken off as the coffle penetrated farther South, where escape was nearly impossible. But since the customary way of disposing of a troublesome slave—whether criminally insane, indomitably rebellious, or merely a repeated runaway—was to sell him or her down South, drivers assumed that the captives could be dangerous. Coffles were doubly vulnerable, for robbery and for revolt, so security was high.

The captives were not generally allowed to talk among themselves as they tramped along, but sometimes, in the midst of their suffering, they were made to sing. The English geologist G. W. Featherstonhaugh, who in 1834 happened upon the huge annual Natchez-bound chain gang led by trader John Armfield, noted that “the slave-drivers … endeavour to mitigate their discontent by feeding them well on the march, and by encouraging them”—encouraging them?—“to sing ‘Old Virginia never tire,’ to the banjo.”9 Thomas William Humes, who saw coffles of Virginia-born people passing through Tennessee in shackles on the way to market, wrote: “It was pathetic to see them march, thus bound, through the towns, and to hear their melodious voices in plaintive singing as they went.”10

Sometimes coffles marched with fiddlers at the head. North Carolina clergyman Jethro Rumple recalled them stepping off with a huzzah: “On the day of departure for the West the trader would have a grand jollification. A band, or at least a drum and fife, would be called into requisition, and perhaps a little rum be judiciously distributed to heighten the spirits of his sable property, and the neighbors would gather in to see the departure.”11 Rumple was speaking, needless to say, of “heightening the spirits” of young people who had just been ripped away from their parents and were being taken to a fate many equated, not incorrectly, with death.

A coffle might leave a slave jail with more people than it arrived with. The formerly enslaved Sis Shackleford described the process at Virginia’s Five Forks Depot (as transcribed by the interviewer):

Had a slave-jail built at de cross roads wid iron bars ’cross de winders. Soon’s de coffle git dere, dey bring all de slaves from de jail two at a time an’ string ’em ’long de chain back of de other po’ slaves. Ev’ybody in de village come out—’specially de wives an’ sweethearts and mothers—to see dey solt-off chillun fo’ de las’ time. An’ when dey start de chain a-clankin’ an’ step off down de line, dey all jus’ sing an’ shout an’ make all de noise dey can tryin’ to hide de sorrer in dey hearts an’ cover up de cries an’ moanin’s of dem dey’s leavin’ behin’.12

An enslaved person could always be sold to another owner, at any time. When Louis Hughes’s coffle reached Edenton, Georgia, McGee sold twenty-one of his newly purchased captives, taking advantage of the price differential in the Lower South to post an immediate profit on a third of his Virginia transaction and thereby hedge his debt to his financier.

Charles Ball described a deal that took place on the road in South Carolina:

The stranger, who was a thin, weather-beaten, sunburned figure, then said, he wanted a couple of breeding wenches, and would give as much for them as they would bring in Georgia…. He then walked along our line, as we stood chained together, and looked at the whole of us—then turning to the women; asked the prices of the two pregnant ones.

Our master replied, that these were two of the best breeding-wenches in all Maryland—that one was twenty-two, and the other only nineteen—that the first was already the mother of seven children, and the other of four—that he had himself seen the children at the time he bought their mothers—and that such wenches would be cheap at a thousand dollars each; but as they were not able to keep up with the gang, he would take twelve hundred

dollars for the two. The purchaser said this was too much, but that he would give nine hundred dollars for the pair.

This price was promptly refused; but our master, after some consideration, said he was willing to sell a bargain in these wenches, and would take eleven hundred dollars for them, which was objected to on the other side; and many faults and failings were pointed out in the merchandise. After much bargaining, and many gross jests on the part of the stranger, he offered a thousand dollars for the two, and said he would give no more. He then mounted his horse, and moved off; but after he had gone about one hundred yards, he was called back; and our master said, if he would go with him to the next blacksmith’s shop on the road to Columbia, and pay for taking the irons off the rest of us, he might have the two women.13 (paragraphing added)

Women with babies in hand were in a particularly cruel situation. Babies weren’t worth much money, and they slowed down coffles. William Wells Brown, hired out to a slave trader named Walker, recalled seeing a baby given away on the road:

Soon after we left St. Charles, the young child grew very cross, and kept up a noise during the greater part of the day. Mr. Walker complained of its crying several times, and told the mother to stop the child’s d——d noise, or he would. The woman tried to keep the child from crying, but could not. We put up at night with an acquaintance of Mr. Walker, and in the morning, just as we were about to start, the child again commenced crying. Walker stepped up to her, and told her to give the child to him. The mother tremblingly obeyed. He took the child by one arm, as you would a cat by the leg, walked into the house, and said to the lady,“Madam, I will make you a present of this little ******; it keeps such a noise that I can’t bear it.”

“Thank you, sir,” said the lady.14

From the first American coffles on rough wilderness treks along trails established by the indigenous people, they were the cheapest and most common way to transport captives from one region to another.

The federally built National (or Cumberland) Road, which by 1818 reached the Ohio River port of Wheeling, Virginia (subsequently West Virginia), was ideal for coffles. It was the nation’s first paved highway, with bridges across every creek. Laying out approximately the route of the future US 40, its broken-stone surface provided a westward overland transportation link that began at the Potomac River port of Cumberland, Maryland. From Wheeling, the captives could be shipped by riverboat down to the Mississippi River and on to the Deep South’s second-largest slave market at Natchez, or further on to the nation’s largest slave market, New Orleans.

Beginning after the War of 1812 and continuing up through secession, captive African Americans were trafficked south and west by every possible method, in an enormous forced migration. “A drove of slaves on a southern steamboat, bound for the cotton or sugar regions,” wrote William Wells Brown in his 1849 autobiography, “is an occurrence so common, that no one, not even the passengers, appear to notice it, though they clank their chains at every step.”15

As railroads extended their reach, captives were packed like cattle into freight cars, shortening the time and expense to market considerably. Some passenger trains had “servant cars,” though a cruder term was more commonly used. On his first trip to the South, in January 1859, the twenty-one-year-old New Englander J. Pierpont Morgan noted: “1000 slaves on train.”16

They were trafficked by sea in oceangoing vessels that sailed the hard passage from the Chesapeake around the Florida peninsula to New Orleans, as well as in shorter voyages within that route. Ocean shipment was more expensive than a coffle, but it was quicker, so it turned the capital-intensive human cargo over more efficiently. Though exact figures do not exist, it is safe to say that tens of thousands of African Americans made the coastwise voyage from the Chesapeake and from Charleston to New Orleans and up the Mississippi to Natchez, as well as to Pensacola, Mobile, Galveston, and other ports. Maryland ports alone (principally Baltimore) shipped out 11,966 people for whom records exist between 1818 and 1853, and an unknown number of others before, during, and after that time.17

More slave ships came to New Orleans from the East Coast of the United States than from Africa. In a shorter recapitulation of the Middle Passage of a century before, the captives were packed into the hold with ventilation slats along the side to keep them from suffocating. Upon arrival, they were discharged into one or another of New Orleans’s many slave pens, where they were washed, groomed, and fed, their skin was oiled, and their gray hairs, if they had any, were dyed or plucked out. On sale day, they were put into suits of the finest clothes many of them would ever wear, with perhaps even top hats for the men. Most would be sent to the cotton fields, where inhuman levels of work would be extracted from them through torture, or to Louisiana’s death camps of sugar.

Following the precedent set by the Europeans, who referred to the coastal regions of Africa by their exports—the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast, the Slave Coast—some writers have referred to the Chesapeake region as the Tobacco Coast.

But it would also be appropriate to call it the American Slave Coast.

For the very, very, very, very few of you peeps who still read anything longer than 300 words. This book details the $$$$$$ capital accumulation based upon forcibly bred African women in Virginia whose offspring were sold to plantation death camp owners in the deep South. The documentation of this Hell-ocaust was chronicled by a Black man in 1897. This book uses his facts along with historically preserved records to literally recreate for the reader the horrors that African people endured under the complete dehumanization of AmeriKKKa's $$$$$$$ barbaric conscienceless morally deprived chattel slavery. AmeriKKKa's global wealth was created by slavery. Slave breeders & sellers could make cash quicker than the planters who could be wiped out by low prices for their crops or a weather catastrophe. This very rarely discussed part of American history is rarely talked about due to it's horror. Read the first chapter below and download and read the whole book. Send a copy to Kanye West who says Slavery was a choice.

Download whole book epub

Code:

https://mega.nz/#!n4URFQRK!ik3EI2T70TiaU7-_EfLi_r55ELknrxXLqLypjAt2EbECHAPTER ONE

THE AMERICAN SLAVE COAST offers a provocative vision of US history from earliest colonial times through emancipation that presents even the most familiar events and figures in a revealing new light.

Authors Ned and Constance Sublette tell the brutal story of how the slavery industry made the reproductive labor of the people it referred to as “breeding women” essential to the young country’s expansion. Captive African Americans in the slave nation were not only laborers, but merchandise and collateral all at once. in a land without silver, gold, or trustworthy paper money, their children and their children’s children into perpetuity were used as human savings accounts that functioned as the basis of money and credit in a market premised on the continual expansion of slavery. Slaveowners collected interest in the form of newborns, who had a cash value at birth and whose mothers had no legal right to say no to forced mating.

This gripping narrative is driven by the power struggle between the elites of Virginia, the slave-raising “mother of slavery,” and South Carolina, the massive importer of Africans—a conflict that was central to American politics from the making of the Constitution through the debacle of the Confederacy.

Virginia slaveowners won a major victory when Thomas Jefferson’s 1808 prohibition of the African slave trade protected the domestic slave markets for slave-breeding. The interstate slave trade exploded in mississippi during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, drove the US expansion into Texas, and powered attempts to take over Cuba and other parts of Latin America, until a disaffected South Carolina spearheaded the drive to secession and war, pushing the Virginians to secede or lose their slave-breeding industry.

Filled with surprising facts, fascinating incidents, and startling portraits of the people who made, endured, and resisted the slave-breeding industry, The American Slave Coast culminates in the revolutionary Emancipation Proclamation, which at last decommissioned the capitalized womb and armed the African Americans to fight for their freedom.

Introduction

THIS IS A HISTORY of the slave-breeding industry, which we define as the complex of businesses and individuals in the United States who profited from the enslavement of African American children at birth.

At the heart of our account is the intricate connection between the legal fact of people as property—the “chattel principle”—and national expansion. Our narrative doubles, then, as a history of the making of the United States as seen from the point of view of the slave trade.

It also traces the history of money in America. In the Southern United States, the “peculiar institution” of slavery was inextricably associated with its own peculiar economy, interconnected with that of the North.

One of the two principal products of the antebellum slave economy was staple crops, which provided the cash flow—primarily cotton, which was the United States’ major export. The other was enslaved people, who counted as capital and functioned as the stable wealth of the South. African American bodies and childbearing potential collateralized massive amounts of credit, the use of which made slaveowners the wealthiest people in the country. When the Southern states seceded to form the Confederacy they partitioned off, and declared independence for, their economic system in which people were money.

Our chronology reaches from earliest colonial times through emancipation, following the two main phases of the slave trade. The first phase, importation, began with the first known sale of kidnapped Africans in Virginia in 1619 and took place largely, though not entirely, during the colonial years. The second phase, breeding, was the era of the domestic, or interstate, slave trade in African Americans. The key date here—from our perspective, one of the most important dates in American history—was the federal prohibition of the “importation of persons” as of January 1, 1808. After that, the interstate trade was, with minor exceptions, the only slave trade in the United States, and it became massified on a previously impossible scale.

The conflict between North and South is a fundamental trope of American history, but in our narrative, the major conflict is intra-Southern: the commercial antagonism between Virginia, the great slave breeder, and South Carolina, the great slave importer, for control of the market that supplied slave labor to an expanding slavery nation. The dramatic power struggle between the two was central to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 and to secession in 1860–61.

Part One is an overview, intended as an extended introduction to the

subject.

Part Two, which begins the main chronological body of the text, describes the creation of a slave economy during the colonial years.

Part Three centers on the US Constitution’s role as hinge between the two phases of slave importation and slave breeding.

Parts Four through Six cover the years of the slave-breeding industry, from the end of the War of 1812 through emancipation: the rise, peak, and fall of the cotton kingdom.

Note: This book describes an economy in which people were capital, children were interest, and women were routinely violated. We have tried to avoid gratuitously subjecting the reader to offensive language and images, but we are describing a horrifying reality.

The Mother of Slavery

“VIRGINIA WAS THE MOTHER of slavery,” wrote Louis Hughes.

It wasn’t just a figure of speech.

During the fifty-three years from the prohibition of the African slave trade by federal law in 1808 to the debacle of the Confederate States of America in 1861, the Southern economy depended on the functioning of a slave-breeding industry, of which Virginia was the number-one supplier. When Hughes was born in 1832, the market was expanding sharply.

“My father was a white man and my mother a negress,” Hughes wrote.1 That meant he was classified as merchandise at birth, because children inherited the free or enslaved status of the mother, not the father. It had been that way in Virginia for 170 years already when Hughes was born.

Partus sequitur ventrem was the legal term: the status of the newborn follows the status of the womb. Fathers passed inheritances down, mothers passed slavery down. It ensured a steady flow of salable human product from the wombs of women who had no legal right to say no.

Most enslaved African Americans lived and died without writing so much as their names. The Virginia legal code of 1849 provided for “stripes”—flogging—for those who tried to acquire literacy skills. A free person who dared “assemble with negroes for the purpose of instructing them to read or write” could receive a jail sentence of up to six months and a fine of up to a hundred dollars, plus costs.2 An enslaved person who tried to teach others to read might have part of a finger chopped off by the slaveowner, with the full blessing of law.

So it was an especially distinguished achievement when in 1897 the sixty-four-year-old Louis Hughes published his memoir, titled Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom: The Institution of Slavery as Seen on the Plantation and in the Home of the Planter. Like the other volumes collectively referred to as slave narratives, it bears witness to a history slaveowners did not want to exist: the firsthand testimony of the enslaved.

By the time Hughes was twelve, he had been sold five times. The third time, he was sold away from his mother to a trader. “It was sad to her to part with me,” he recalled, “though she did not know that she was never to see me again, for my master had said nothing to her regarding his purpose and she only thought, as I did, that I was hired to work on the canal-boat,and that she should see me occasionally. But alas! We never met again.”

Louis Hughes’s author photograph.

The trader carried the boy away from the Charlottesville area that had been his home, down the James River to Richmond. There he was sold a fourth time, to a local man, but Hughes “suffered with chills and fever,” so the dissatisfied purchaser had him resold. This time he went on the auction block, where he was bought by a cotton planter setting up in Pontotoc, Mississippi—a booming region that had recently become available for plantations in the wake of the delivery of large areas of expropriated Chickasaw land into the hands of speculators.

Slaves were designated by geographical origin in the market, with Virginia-and Maryland-born slaves commanding a premium. “It was held by many that [Virginia] had the best slaves,” Hughes wrote. “So when Mr. McGee found I was born and bred in that state he seemed satisfied. The bidding commenced, and I remember well when the auctioneer said: ‘Three hundred eighty dollars—once, twice and sold to Mr. Edward McGee.’”3

McGee had plenty of financing, and he was in a hurry; he bought sixty other people that day.4 A prime field hand would have commanded double or more, but even so, the $380 that bought the sickly twelve-year-old would be more than $10,000 in 2014 money.5

Like the largest number of those forcibly emigrated to the Deep South, McGee’s captives were all made to walk from Virginia to Mississippi, in a coffle.

Southern children grew up seeing coffles approach in a cloud of dust.

A coffle is “a train of men or beasts fastened together,” says the Oxford English Dictionary, and indeed Louis Hughes referred to the coffle he marched in as “a herd.”6 The word comes from the Arabic qafilah, meaning “caravan,” recalling the overland slave trade that existed across the desert from sub-Saharan Africa to the greater Islamic world centuries before Columbus crossed the Atlantic. With the development in the late fifteenth century of the maritime trade that shifted the commercial gravity of Africa southward from the desert to the Atlantic coast, coffles were used to traffic Africans from point of capture in their homeland to point of sale in one of Africa’s many slave ports.

But the people trudging to Mississippi along with Louis Hughes were not Africans. They were African Americans, born into slavery and raised with their eventual sale in mind. Force-marched through wilderness at a pace of twenty or twenty-five miles a day, for five weeks or more, from can’t-see to can’t-see, in blazing sun or cold rain, crossing unbridged rivers, occasionally dropping dead in their tracks, hundreds of thousands of laborers transported themselves down south at gunpoint, where they and all their descendants could expect to be prisoners for life.

Perhaps 80 percent of enslaved children were born to two-parent families—though the mother and father might live on different plantations—but in extant slave-traders’ records of those sold, according to Michael Tadman’s analysis, “complete nuclear families were almost totally absent.” About a quarter of those trafficked southward were children between eight and fifteen, purchased away from their families. The majority of coffle prisoners were male: boys who would never again see their mothers, men who would never again see wives and children.

But there were women and girls in the coffles, too—exposed, as were enslaved women everywhere, to the possibility of sexual violation from their captors. The only age bracket in which females outnumbered males in the trade was twelve to fifteen, when they were as able as the boys to do field labor, and could also bear children.7 Charles Ball, forcibly taken from Maryland to South Carolina in 1805, recalled that The women were merely tied together with a rope, about the size of a bed cord, which was tied like a halter round the neck of each; but the men … were very differently caparisoned. A strong iron collar was closely fitted by means of a padlock round each of our necks. A chain of iron, about a hundred feet in length, was passed through the hasp of each padlock, except at the two ends, where the hasps of the padlocks passed through a link of the chain. In addition to this, we were handcuffed in pairs, with iron staples and bolts, with a short chain, about a foot long, uniting the handcuffs and their wearers in pairs.8

As they tramped along, coffles were typically watched over by whip- and gun-wielding men on horseback and a few dogs, with supply wagons bringing up the rear. In the country coffles slept outdoors on the ground, perhaps in tents; in town they slept in the local jail or in a slave trader’s private jail. Farmers along the route did business with the drivers, selling them quantities of the undernourishing, monotonous fare that enslaved people ate day in and day out.

Sometimes the manacles were taken off as the coffle penetrated farther South, where escape was nearly impossible. But since the customary way of disposing of a troublesome slave—whether criminally insane, indomitably rebellious, or merely a repeated runaway—was to sell him or her down South, drivers assumed that the captives could be dangerous. Coffles were doubly vulnerable, for robbery and for revolt, so security was high.

The captives were not generally allowed to talk among themselves as they tramped along, but sometimes, in the midst of their suffering, they were made to sing. The English geologist G. W. Featherstonhaugh, who in 1834 happened upon the huge annual Natchez-bound chain gang led by trader John Armfield, noted that “the slave-drivers … endeavour to mitigate their discontent by feeding them well on the march, and by encouraging them”—encouraging them?—“to sing ‘Old Virginia never tire,’ to the banjo.”9 Thomas William Humes, who saw coffles of Virginia-born people passing through Tennessee in shackles on the way to market, wrote: “It was pathetic to see them march, thus bound, through the towns, and to hear their melodious voices in plaintive singing as they went.”10

Sometimes coffles marched with fiddlers at the head. North Carolina clergyman Jethro Rumple recalled them stepping off with a huzzah: “On the day of departure for the West the trader would have a grand jollification. A band, or at least a drum and fife, would be called into requisition, and perhaps a little rum be judiciously distributed to heighten the spirits of his sable property, and the neighbors would gather in to see the departure.”11 Rumple was speaking, needless to say, of “heightening the spirits” of young people who had just been ripped away from their parents and were being taken to a fate many equated, not incorrectly, with death.

A coffle might leave a slave jail with more people than it arrived with. The formerly enslaved Sis Shackleford described the process at Virginia’s Five Forks Depot (as transcribed by the interviewer):

Had a slave-jail built at de cross roads wid iron bars ’cross de winders. Soon’s de coffle git dere, dey bring all de slaves from de jail two at a time an’ string ’em ’long de chain back of de other po’ slaves. Ev’ybody in de village come out—’specially de wives an’ sweethearts and mothers—to see dey solt-off chillun fo’ de las’ time. An’ when dey start de chain a-clankin’ an’ step off down de line, dey all jus’ sing an’ shout an’ make all de noise dey can tryin’ to hide de sorrer in dey hearts an’ cover up de cries an’ moanin’s of dem dey’s leavin’ behin’.12

An enslaved person could always be sold to another owner, at any time. When Louis Hughes’s coffle reached Edenton, Georgia, McGee sold twenty-one of his newly purchased captives, taking advantage of the price differential in the Lower South to post an immediate profit on a third of his Virginia transaction and thereby hedge his debt to his financier.

Charles Ball described a deal that took place on the road in South Carolina:

The stranger, who was a thin, weather-beaten, sunburned figure, then said, he wanted a couple of breeding wenches, and would give as much for them as they would bring in Georgia…. He then walked along our line, as we stood chained together, and looked at the whole of us—then turning to the women; asked the prices of the two pregnant ones.

Our master replied, that these were two of the best breeding-wenches in all Maryland—that one was twenty-two, and the other only nineteen—that the first was already the mother of seven children, and the other of four—that he had himself seen the children at the time he bought their mothers—and that such wenches would be cheap at a thousand dollars each; but as they were not able to keep up with the gang, he would take twelve hundred

dollars for the two. The purchaser said this was too much, but that he would give nine hundred dollars for the pair.

This price was promptly refused; but our master, after some consideration, said he was willing to sell a bargain in these wenches, and would take eleven hundred dollars for them, which was objected to on the other side; and many faults and failings were pointed out in the merchandise. After much bargaining, and many gross jests on the part of the stranger, he offered a thousand dollars for the two, and said he would give no more. He then mounted his horse, and moved off; but after he had gone about one hundred yards, he was called back; and our master said, if he would go with him to the next blacksmith’s shop on the road to Columbia, and pay for taking the irons off the rest of us, he might have the two women.13 (paragraphing added)

Women with babies in hand were in a particularly cruel situation. Babies weren’t worth much money, and they slowed down coffles. William Wells Brown, hired out to a slave trader named Walker, recalled seeing a baby given away on the road:

Soon after we left St. Charles, the young child grew very cross, and kept up a noise during the greater part of the day. Mr. Walker complained of its crying several times, and told the mother to stop the child’s d——d noise, or he would. The woman tried to keep the child from crying, but could not. We put up at night with an acquaintance of Mr. Walker, and in the morning, just as we were about to start, the child again commenced crying. Walker stepped up to her, and told her to give the child to him. The mother tremblingly obeyed. He took the child by one arm, as you would a cat by the leg, walked into the house, and said to the lady,“Madam, I will make you a present of this little ******; it keeps such a noise that I can’t bear it.”

“Thank you, sir,” said the lady.14

From the first American coffles on rough wilderness treks along trails established by the indigenous people, they were the cheapest and most common way to transport captives from one region to another.

The federally built National (or Cumberland) Road, which by 1818 reached the Ohio River port of Wheeling, Virginia (subsequently West Virginia), was ideal for coffles. It was the nation’s first paved highway, with bridges across every creek. Laying out approximately the route of the future US 40, its broken-stone surface provided a westward overland transportation link that began at the Potomac River port of Cumberland, Maryland. From Wheeling, the captives could be shipped by riverboat down to the Mississippi River and on to the Deep South’s second-largest slave market at Natchez, or further on to the nation’s largest slave market, New Orleans.

Beginning after the War of 1812 and continuing up through secession, captive African Americans were trafficked south and west by every possible method, in an enormous forced migration. “A drove of slaves on a southern steamboat, bound for the cotton or sugar regions,” wrote William Wells Brown in his 1849 autobiography, “is an occurrence so common, that no one, not even the passengers, appear to notice it, though they clank their chains at every step.”15

As railroads extended their reach, captives were packed like cattle into freight cars, shortening the time and expense to market considerably. Some passenger trains had “servant cars,” though a cruder term was more commonly used. On his first trip to the South, in January 1859, the twenty-one-year-old New Englander J. Pierpont Morgan noted: “1000 slaves on train.”16

They were trafficked by sea in oceangoing vessels that sailed the hard passage from the Chesapeake around the Florida peninsula to New Orleans, as well as in shorter voyages within that route. Ocean shipment was more expensive than a coffle, but it was quicker, so it turned the capital-intensive human cargo over more efficiently. Though exact figures do not exist, it is safe to say that tens of thousands of African Americans made the coastwise voyage from the Chesapeake and from Charleston to New Orleans and up the Mississippi to Natchez, as well as to Pensacola, Mobile, Galveston, and other ports. Maryland ports alone (principally Baltimore) shipped out 11,966 people for whom records exist between 1818 and 1853, and an unknown number of others before, during, and after that time.17

More slave ships came to New Orleans from the East Coast of the United States than from Africa. In a shorter recapitulation of the Middle Passage of a century before, the captives were packed into the hold with ventilation slats along the side to keep them from suffocating. Upon arrival, they were discharged into one or another of New Orleans’s many slave pens, where they were washed, groomed, and fed, their skin was oiled, and their gray hairs, if they had any, were dyed or plucked out. On sale day, they were put into suits of the finest clothes many of them would ever wear, with perhaps even top hats for the men. Most would be sent to the cotton fields, where inhuman levels of work would be extracted from them through torture, or to Louisiana’s death camps of sugar.

Following the precedent set by the Europeans, who referred to the coastal regions of Africa by their exports—the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast, the Slave Coast—some writers have referred to the Chesapeake region as the Tobacco Coast.

But it would also be appropriate to call it the American Slave Coast.