Africatown Heritage House opening:

Public events, festivities to know about

Published: July 6, 2023

Lorna Gail Woods, a leader of the community descended from survivors of the slave ship Clotilda's final voyage, carries a wreath during a ceremony on July 9, 2022, marking the anniversary of the ship's arrival. The 2023 Landing ceremony will take place on the morning of Saturday, July 8, 2023. Lawrence Specker |

LSpecker@AL.com

By

Lawrence Specker | lspecker@al.com

If you were hoping to get into the

Africatown Heritage House on opening day, you’re out of luck: Every available tour has been booked up. But the weekend brings several other opportunities to get in on the celebrations.

The opening of the Heritage House on Saturday promises to be a watershed moment for a community seeking to capitalize on growing interest in its unique story. The facility will provide a much-needed point of entry for visitors, which hasn’t had one since Hurricane Katrina damaged an old welcome center in 2005.

Millions of dollars in funding have been committed to a new Welcome Center, but it’s still

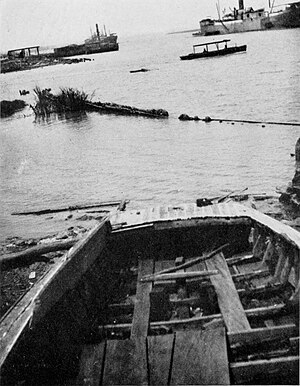

in the process of being designed. Meanwhile the Heritage House will provide the first public display of materials from the slave ship

Clotilda.

The Africatown Heritage House as pictured on

Thursday, January 26, 2023, in Mobile, Ala.

(John Sharp/

jsharp@al.com).

The Heritage House website,

Clotilda.com, describes its Clotilda exhibition as a 2,500-square-foot display that addresses the final voyage of the slave ship Clotilda, its survivors and the community they founded:

“‘Clotilda: The Exhibition’ will cover the story of the Clotilda with a special focus on the people of the story – their individuality, their perseverance, and the extraordinary community they established. The exhibition tells the story of the 110 remarkable men, women and children, from their West African beginnings, to their enslavement, to their settlement of Africatown, and finally the discovery of the sunken schooner, all through a combination of interpretive text panels, documents, and artifacts. The pieces of the Clotilda that have been recovered from the site of the wreck will be on display in the exhibition, on loan from the Alabama Historical Commission. The exhibition has been curated, developed, and designed in conjunction with the local community and the wider descendent community, and in consultation with experts around the country.”

Speaking at a recent meeting of the Africatown community group CHESS, Heritage House director Jessica Fairley said that the museum’s opening exhibition features audio narration. To ensure that an audio device is available for every visitor, the timed tours allow 25 people to enter every 20 minutes. Fairley said that once people are inside, they’re welcome to stay as long as they want.

After Saturday’s events the Heritage House will begin regular operations. The facility will be open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday. Advance reservations are recommended; timed tickets can be reserved at

clotilda.com/visit-us. As of Thursday, July 6, it appeared that tickets were available throughout the week of July 11-15.

Admission is free for residents of Mobile County, though donations are encouraged. Regular admission prices are $15 for adults; $9 for seniors, active and retired military personnel and students over 18; $8 for children ages 6-18; free for children 5 and younger; and free for members of the History Museum of Mobile.

While the tour schedule for Saturday is booked up, other public events coincide with the opening. Details follow.

Opening weekend highlights:

9 a.m. Friday, July 7: A building dedication for the Africatown Heritage House will take place in the Memorial Garden outside the facility at 2465 Winbush St. The hourlong program will feature remarks from dignitaries including Mobile County District 1 Commissioner Merceria Ludgood; Lisa D. Jones, executive director of the Alabama Historical Commission; state Sen. Vivian Davis Figures; state Rep. Adline Clarke; Mobile County Commission president Connie Hudson; Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson; Mobile City Councilman William Carroll; Altevese Rosario, vice president of the Clotilda Descendants Association; History Museum of Mobile Director Meg McCrummen Fowler; and pastors from each of the three historic Africatown churches. The event also will feature a performance by the African Cultural Alliance of Egbe Oya.

7 a.m. Saturday, July 8: The Africatown Plateau Pacers will hold their second annual community 5k walk. While the event is not a part of the official Heritage House program, it offers an opportunity to walk through historic Plateau and Africatown and learn about the Plateau community. The walk starts at Kidd Park, 800 East St. Registration without a T-shirt is $15, $25 or $27 with shirt. To register in advance, visit

raceroster.com. Proceeds benefit the Pacers’ scholarship fund. For information, visit the

Africatown Plateau Pacers page on Facebook.

8 a.m. Saturday, July 8: The Clotilda Descendants Association will hold “The Landing,”

an annual ceremony commemorating the arrival of the 110 captives carried aboard the Clotilda. The ceremony will be held under the Africatown Bridge, with shuttle service available from Union Baptist Church starting at 7:30 a.m. The site of the ceremony can be found by searching for 101 Bay Bridge Road. Attendees are asked to arrive at the site by 8 a.m. in order to avoid disrupting the 8:15 a.m. ceremony.

10 a.m. Saturday, July 8: The Africatown Heritage House opens to the public. According to information release by Mobile County, “Entrance will be granted to timed ticket holders only. The exhibit will close at 5 p.m. Opening day is sold out. Absolutely no one will be admitted on July 8 without a pre-booked, timed ticket.”

11 a.m. Saturday, July 8: An Africatown Community Day celebration will be held on the grounds of the Robert L. Hope Community Center from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. The event is free and open to the public. Planned attractions include: Egungun masquerade parade and performance by the African Cultural Alliance of Egbe Oya; musical performances by the Vigor High School marching band, the Voices of Africatown Mass Choir, Symone French, and Ted Keeby & the MoJazz Band; spoken-word performances; children’s activities; food trucks; and drumming workshops by Wayne Curtis and the Mobile Area Africatown Drummers.

According to information released by Mobile County, “Attendees are encouraged to bring lawn chairs. There will be limited tent seating. Umbrellas and pop-up tents are allowed, but the City of Mobile does not allow stakes in the Hope Center lawn.”

Winbush and Edwards streets will be closed to through traffic on July 8. Bus and golf cart shuttles to the Hope Center and the adjacent Heritage House will run from parking lots at several sites: First Hopewell Missionary Baptist Church at 664 Shelby Street, Yorktown Missionary Baptist Church at 851 East Street, Union Missionary Baptist Church at 506 Africatown Boulevard, Shell Bayou Elks Lodge at 456 Africatown Boulevard, the ACDC Farmers Market site at Shelby Street near Tin Top Lane and Mobile County Training School’s baseball field on McKinley Street.

According to the county, “Drivers should not block any Africatown street when parking and please respect the private property within the neighborhoods near the celebration site. There will be no parking at the Robert Hope Community Center or Africatown Heritage House or on the following streets for bus and shuttle access: Edwards St., Edwards Ave., Shelby St., Tin Top Lane, Green St., Susie Ansley St., Peter Lee St.” Parking also is “highly discouraged” at the Kidd Park swimming pool because of an event there.

More on Africatown:

Worries over Clotilda owner’s artifacts surface ahead of Africatown Heritage House opening

Africatown ancestors honored on anniversary of Clotilda’s arrival

Mobile holds first public meeting on design of Africatown Welcome Center

Heritage House tours are booked up on Saturday as the facility opens, but other ceremonies and celebrations offer a chance to participate.

www.al.com