https://newrepublic.com/article/147...ial&utm_medium=facebook&utm_campaign=sharebtn

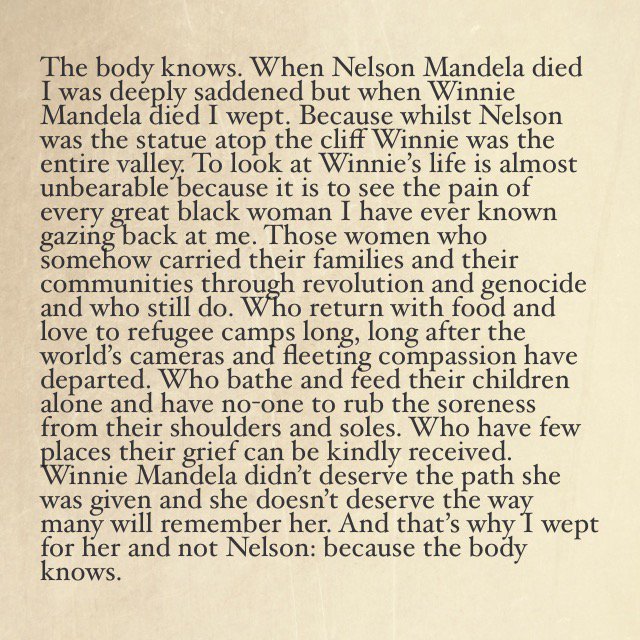

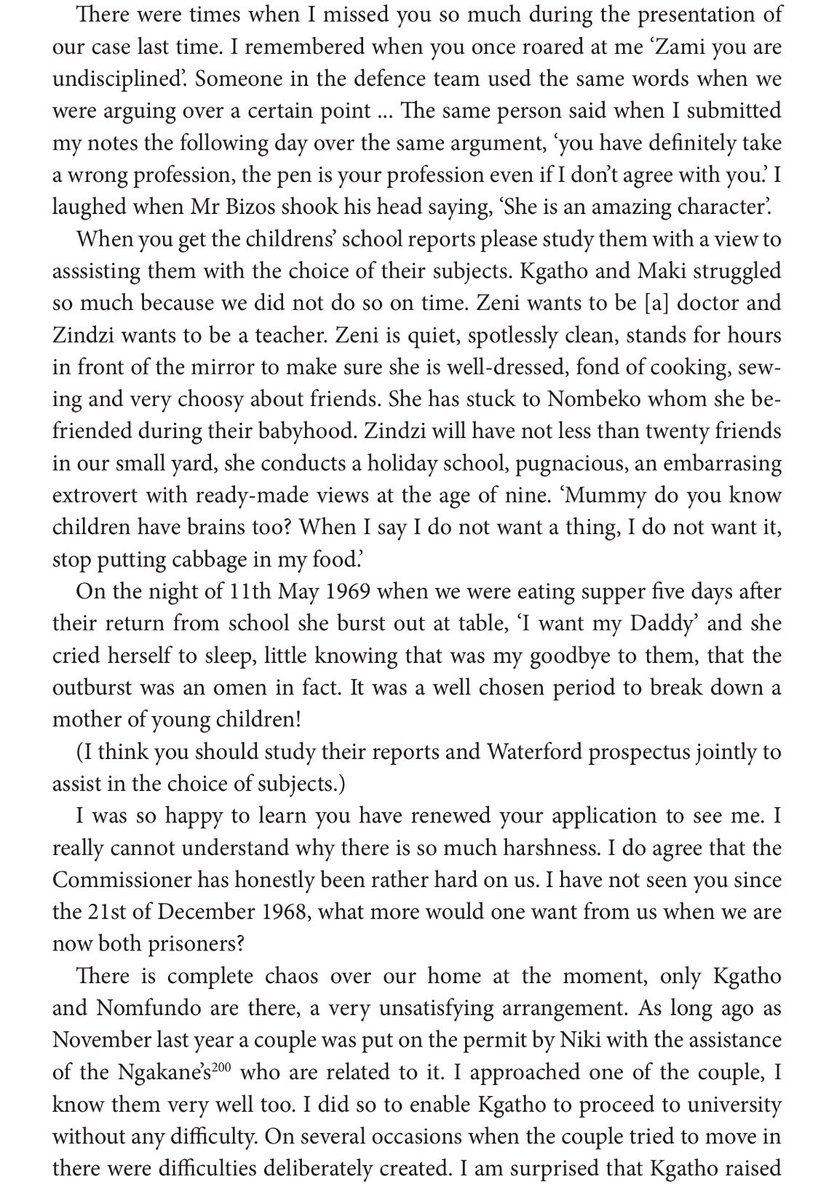

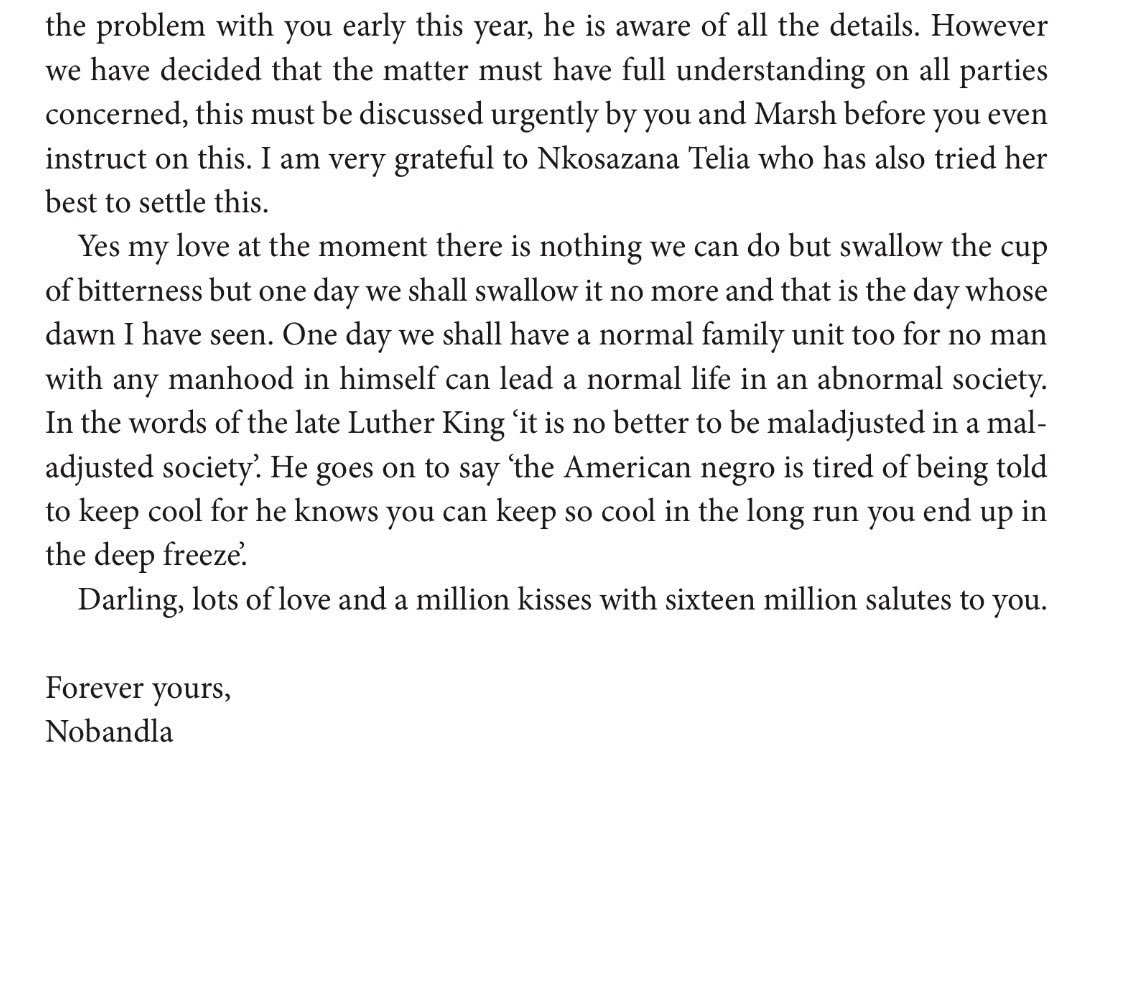

The Scapegoating of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela

On the strange afterlife of a figure who embodied post-apartheid South Africa’s contradictions and failings

By EVE FAIRBANKS

April 5, 2018

Updated on April 5 at 6:44 AM.

A few months after I moved to South Africa in 2009, I expressed the wish to meet Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Nelson Mandela’s ex-wife, to a friend of mine. This friend was a political activist who’d been present at many epochal moments of the struggle against apartheid in the 1980s and the remaking of the nation in the 1990s. Eager to get me acquainted with the country’s history, he normally answered nearly every message I wrote to him within the hour. Except for my request about Winnie. Several notes and text messages about Winnie got no reply, until finally he called me back. In a pained voice, he asked, “Aren’t you sure you wouldn’t rather meet Graca”—Nelson Mandela’s third, less controversial wife?

When Winnie died this week, one South African friend of mine wrote of her “tremendous love and admiration” for Madikizela-Mandela on Facebook. “Thank you Winnie Mandela for what you sacrificed for all of us,” the country’s leading educator, a university professor, wrote. South Africa’s most famous radio host declared her “the gold standard of rage as moral uprightness.” “Rest as you lived, fiercely in power,” a fourth friend, an academic, said. The plaudits were as loving overseas. The Women’s March

released a statement, and Jennifer Hudson and Forest Whitaker

tweeted praise.

The outpouring of emotion at Madikizela-Mandela’s death startled me, because it ran in contrast to the mix of emotions expressed towards her while she was alive. Unfortunately, I never got to meet the “Mother of the Nation,” as she was honorifically called. But reading the local papers over the years, I got the impression she was a person—maybe

the person—the country didn’t like to think about too much, or too deeply.Another friend, who offered to bring me to see Winnie in the township of Soweto just a couple weeks ago—she was generous with guests, especially the poor—whispered to me that, when I met her, I would hear “truths” that South Africa liked, as a country, to avoid. Another black South African writer I know lamented to me that, while she was alive, some people who liked to think of themselves as “savvy” treated her as “a bit of a joke, or someone to subtly ignore.” She didn’t represent South Africa abroad. When I visited the house she once shared with Nelson Mandela in Soweto, an official with the African National Congress (ANC)—the movement she and Mandela co-created—told me that it was “too bad” Winnie still had some authority over the house, because the detritus of her real life interfered with the house’s “coherence” as a historical monument. He complained that the house didn’t “look right” because it wasn’t appropriately “preserved.”

Indeed, Winnie interfered with the whole South African story. She came to represent what might have happened if a different turn had been made at a fork in the path. Never imprisoned on Robben Island but exiled from Johannesburg and put under house arrest by the white-run police in the 1980s, she broke with the ANC’s dedication to nonviolence and encouraged a harder stand, including pursuing supposed collaborators with the white regime; this stance led to the gruesome 1989 murder of a 14-year-old black boy in her charge, Stompie Sepei. She never agreed to completely forgive white or wealthy South Africans like her husband did; she also held to account leaders of color she believed had chummed up too much with elites and their institutions. A few years ago, she

told a British writer that Mandela had sold out and negotiated a “bad deal” for black people. She dared to call Archbishop Desmond Tutu, one of the few leaders everybody in the world can celebrate for his unbending faith in the power of “joy,” a “cretin.” At her 1997 Truth and Reconciliation hearing, discussing her alleged involvement in the killing of Sepei, writers noted with awe—and some fear—that her face remained impassive, as if she refused to admit there was anything tragic or unjust about the possibility of such an event, even as she declined to say how much she had been involved.

The same “rage” hailed this week as the “gold standard” was treated with ambivalence while she lived. Winnie’s recent political activism included helping a young politician named Julius Malema, who criticizes the ANC for corruption and for allowing the world’s worst economic inequality to persist in South Africa, and who’s routinely mocked as a dope or a crazy radical by pundits of all colors. She supported a youth movement that pushes for free university education and shuts down South African universities with sometimes-rowdy marches. The same education leader who this week lauded Winnie’s “sacrifices” has

railed against this movement for its “complete disregard for education authority” and tendency to wallow in a “pity pool of past grievances.” The radio host who praised Winnie’s “rage” also recently

warned South Africa that Malema could be the country’s “own Donald Trump.”

In later years, Winnie was relegated to tabloids for her

financial battles with Mandela’s family after his death and her glamorous appearance at her 80th birthday party, leading Twitter to

snark that she must have had Botox or plastic surgery. Now she can do no wrong; alive, she sometimes could do little right. If she took a fancy plane, she herself was mocked as a corrupt sell-out. If she spoke out about politics or supported a protest, she was intemperate. “Winnie likes to be in the limelight for all the wrong reasons,” a black letter-writer to Johannesburg’s main newspaper groused two years ago.

It’s a relief to admire the memory of bravery rather than bravery itself. Winnie in the flesh was a symbol of the uneasy implications and contradictions that lie underneath vague and sweeping calls for things like “resistance”: that the urge to resist, truly and fully embraced, can lead to or even demand violence; that justice can afflict the comfortable, and that the comfortable might include us. Some of those now singing Winnie’s praises make their livings from institutions that might well be shattered if the implications of her political vision were carried to their full conclusion: mining corporations, elite educational institutions. Others live lifestyles whose foundations would be undermined by an honest reckoning of the message she delivered about the dangers of capitalism and of ideologies that insist that happiness is available to everybody, rich or poor, without the need for broad, unsettling, even violent changes to the basic structures of political, economic, and cultural power.

One affluent Johannesburg acquaintance who posted heartbroken messages about Winnie also recently wrote on Facebook that she believed happiness comes down to “raw juicing, “sparkling mountain spa water,” “water aerobics,” and $415 “pamper packages” at a Johannesburg resort. “The difference between an ordinary life and an extraordinary one is only a matter of perspective,” she wrote, and “the extent of your wealth [doesn’t] matter.” Well, Winnie believed that the extent of people’s wealth did matter, and that the poor should be encouraged to demand it—even from people like my Johannesburg acquaintance.

Njabulo Ndebele, who wrote a novel based on the story of Madikizela-Mandela’s’s life, in 2016 penned an

astonishing essay revealing the visceral unease he felt when forced to finally meet her in person. Even while writing the novel, he had avoided doing so for reasons not entirely clear to himself. He found that he was put off by her bodyguards’ worshipful attitude, wondering if it wasn’t the kind of adulation that had historically produced “domineering monsters.” He felt unnerved by her charisma. And he asked himself, if Winnie “does not resolve [her] contradictions ... What is to be believed about her? How reliable can she be? Can she ever be trusted?”

I wondered, reading the essay, whether Ndebele wasn’t also directing these questions at himself. Anybody vested with new power in post-apartheid South Africa wrestles with whether they’ve sold out—with how much they really differ from the power- or status-hungry people they fought against when they were less privileged. Some, commending Madikizela-Mandela now, insist that her flaws should be forgiven because of what the country did to her: exile her, torment her, ignore her voice. The apartheid-era country, they mean. But that offsets the blame. It was post-apartheid South Africa that set her before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for murder, put her on trial for racketeering,

declared her the “Mugger of the Country” in a headline in one of the most widely-read newspapers in Johannesburg, and exiled her by, at times, “subtly ignoring” her.

In history, the scapegoat wasn’t a person who was lambasted over and over; it was a figure, a donkey or a person, that was sent out into the wilderness heaped with symbols of society’s sins in order to expiate them. There’s something of that, strangely, in the tributes to Winnie. Alive, she put a face on and a voice to the country’s failings. She exposed the tension between wanting to preserve norms of respectability and South Africa’s beguiling story and its awareness that it might have betrayed its promises to the most powerless. Now, dead, the messages of her life and beliefs can be acknowledged—but also carried off with her safely into the afterlife, leaving the living less worried that she’ll go off in a direction they can’t predict or do something “intemperate.”

The movie star Noemie Harris, who played Madikizela-Mandela in the 2013 Nelson Mandela biopic

Long Walk to Freedom,

confessed to The Telegraph that she felt “terrified” to meet Winnie and was relieved to find that she “loves gardening and is at peace.” In other words, Winnie was defanged, no longer making her “limelight”-hogging claims that freedom had not, in fact, nearly yet been achieved in South Africa. It was a revealing fantasy: one that imagined a version of Madikizela-Mandela in which she felt contented, as if her vision for South Africa had been realized.

It’s far easier to commend her in death than it was in life, when her still-living presence—her capacity to act—contained the possibility that she would align with new allies or take real actions that would make people uncomfortable. Remembering her allows them to pretend that, somehow, that other fork in the road was really taken, that Winnie’s message was duly heard and received. The house in Soweto that the ANC official lamented for its changeability can finally be still, a perfect picture.

Upon Winnie’s death, many South Africans and foreigners tweeted the phrase “Rest in power.” It’s a strange phrase, because the powerful don’t actually rest. Some years ago, the South African poet Vangi Gantsho got it more on the mark: “

You fought until your name became unspoken,” he wrote about Winnie. Only now that Winnie Madikizela-Mandela is physically powerless is she fully permitted to rest in power.

Eve Fairbanks’ writing has appeared in

The New York Times Magazine,

The New Republic, and other publications.

@evefairbanks

@Cee_Webb

@Cee_Webb