David Chase returns to the masterpiece he’s been unable to escape since it went off the air 14 years ago.

www.vulture.com

ow Do You Follow The Sopranos?

David Chase returns to the masterpiece he’s been unable to escape since it went off the air 14 years ago.

By

Matt Zoller Seitz@mattzollerseitz

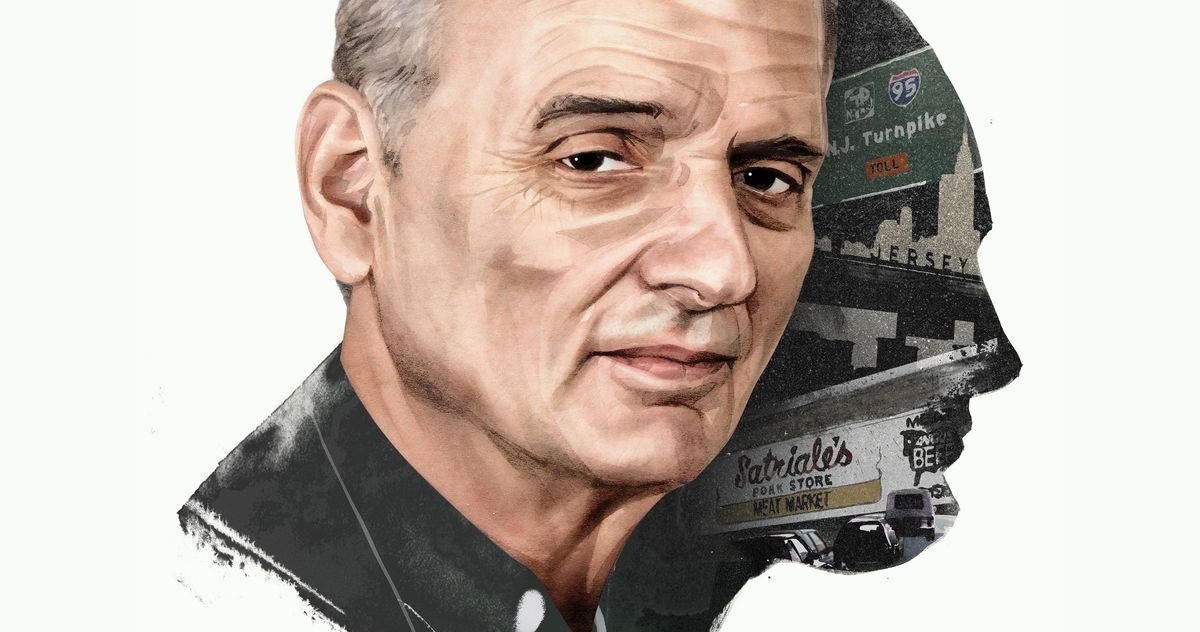

Illustration: Hellovon

David Chase is telling stories again. The 76-year-old creator of

The Sopranos is seated at the kitchen table of a production office in Santa Monica, eating takeout Mexican food and telling me about the time his paternal grandfather, Joseph Fusco, confessed to killing a man. Fusco told the story to a then-12-year-old Chase, who had been sent to Fusco’s apple farm in Hudson, New York, for a week during summer vacation. They were sitting in the kitchen one night after dinner, green apples piled in a bowl between them. “He was telling me he murdered a guy in Buffalo,” Chase recalls. “They got in an argument in a bar. They went outside.” Things escalated — Fusco hit him in the head with a brick. The other guy was a

romano — Roman — though not from his grandfather’s area. “Fusco was bad news. Bad guy.” Chase pauses a moment, staring at his rice and beans in a Styrofoam box. “Who knows if it’s true?” he says finally. “But why would you tell that to an 12-year-old kid who’s staying with you? Who the fuck does that?”

My Week In

New York

A week-in-review newsletter from the people who make

New York Magazine

.

Everything about the anecdote is uncut Chase, from the intensifying violence of the confrontation (you can imagine Chase’s grandfather grabbing the brick off a pile in the bar’s parking lot after realizing he might lose the fight) to the chilling mundanity of a then-middle-aged man relating it to his grandson. It makes me think of all the horrific but realistically awkward brutality meted out during

The Sopranos’ eight-year run — Tony (James Gandolfini), eyes swollen from having Raid sprayed into them, killing another mobster by strangling him and smashing his head against a tiled kitchen floor. It’s also the kind of moment that happens throughout the series’s forthcoming prequel,

The Many Saints of Newark, a panoramic gangster film set in the late ’60s and early ’70s in Newark, New Jersey, directed by Alan Taylor and co-written by Lawrence Konner, both

Sopranos veterans. The film follows junior mobster Christopher Moltisanti’s (Michael Imperioli) father, Newark mob soldier Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola), who was discussed in the original but never portrayed onscreen.

In the 14 years since

The Sopranos ended, Chase has only done one other project: the 2012 rock-and-roll roman à clef

Not Fade Away. He started to write a

Sopranos movie in the summer of 2018, following 11 years of turning down requests from Warner Bros. to make a theatrical spin-off. “Even when Jim was alive, there was talk about doing a literal prequel, with us playing ourselves maybe ten years earlier,” recalls Imperioli, who reprises the role of Christopher as a disembodied voice in a cemetery. “Jim was like, ‘What, are we gonna wear wigs and girdles, like

Star Trek?’ ” Chase was also wary — ever since

The Sopranos, all Hollywood wanted from him was more gangster stories. His attitude was “never — but also, never say never.”

Gandolfini’s death, in 2013, didn’t shut the door. He settled on Dickie Moltisanti as a way to reenter the

Sopranos universe without rehashing the same characters and situations.

The Many Saints is a fall-of-the-old, rise-of-the-new gangster picture, with Dickie struggling to hold on to his position in changing times. But the emotional backbone of the movie is Dickie’s toxic mentorship of the young Tony, played as a teenager by

Gandolfini’s son, Michael. It’s in this plotline that Chase gets to revisit themes that were at the center of the show: the familial, biological, cultural, and historical forces that shape our personalities, for better or worse, in large ways and small, often without our consent or even our knowledge, and how the arc of each person’s life starts to seem incoherent and absurd once you realize it’s all just a collection of poorly sourced, often self-serving anecdotes about people who might not even be alive to corroborate the facts.

Chase has an image as a pessimist provocateur, and he played that up during the run of the show. He did cameos as a bored Italian sneering at

Sopranos character Paulie Walnuts in a Naples café and the voice of God tormenting Tony. He sat for magazine portraits that suggested marble sculptures of doomed Roman senators. He has a look that makes people ask “What are you so depressed about?” even if he isn’t actually sad in that moment. He’s got a warm, lighthearted, even goofy side. Chase loves bad puns and slapstick mayhem. If he takes a liking to you, he’ll text or call just to stay in touch, sometimes at unexpected moments. He’s quick to laugh — an almost childlike giggle that becomes a doubled-over cackle when the jokes turn really dumb. But from my perspective — that of someone who has known David for more than 20 years, ever since I was writing about TV for the Newark

Star-Ledger, the paper that the bathrobe-clad Tony Soprano used to pick up at the end of his driveway — I sense depths of melancholy whenever he circles the reality that he’s pushing 80 and can’t tell all his untold tales in the time he has left, and that even if he could, he’d have trouble getting them made.

From left: James Gandolfini and David Chase. Photo: Getty ImagesMichael Gandolfini and David Chase. Photo: Barry Wetcher/HBO/Barry Wetcher

David is as complicated as any of his fictional creations. He’s a hardware-store owner’s son who had few artistic role models in his family and tried in his youth to be a rock-and-roll musician and then a film director. He settled into network-TV writing in the 1970s and later moved to cable, where he created an uncategorizable series that transformed the industry. “It really challenged movies as vehicles for characterization, honestly,” says Corey Stoll, who plays young Uncle Junior in

The Many Saints. “It’s rare that you could reach the depths of characterization in two hours that you could with 86 hours of a show as complex as

The Sopranos.”

But any expectation that David would have industry carte blanche after the end of

The Sopranos disappeared once the streaming revolution came, shifting the media spotlight away from anti-hero-driven stories set in some version of reality and recentering it on unscripted dramas, competition shows, and blockbuster documentary series; epics like

Game of Thrones and

The Crown, where the sheer hugeness of the production was part of the appeal; and shows that celebrated compassion and kindness, like

Parks and Recreation, Schitt’s Creek, and

Ted Lasso. “I read an article the other day about

Ted Lasso. It basically went, ‘Thank you, Ted Lasso, for relieving us of all these scumbags!’ ” David says, then laughs. “I wanted to say, ‘I wasn’t the one making you watch those other shows, the ones with all the scumbags! You did that to yourself!’ ”

Even as David has worked diligently behind the scenes to try to get different sorts of projects into the pipeline, it seems like he has made peace with the fact that

The Sopranos was the big one, the first-line-in-the-obituary work, the

Citizen Kane of TV, add your own superlatives here, and, inevitably, a hothouse of critical and scholarly analysis (including the book I co-wrote with Alan Sepinwall,

The Sopranos Sessions) and a fandom as belligerent as anything surrounding Marvel, DC, or

Star Wars. (People still fight online over whether

the finale’s cut-to-black means Tony died.) David has participated in

Sopranos podcasts, including

Talking Sopranos, the one co-hosted by former cast members Imperioli and Steve Schirripa; he reads new essays on

The Sopranos and eagerly discusses them with former

Sopranos collaborators. During the lockdown, a number of pieces were published by queer and trans writers embracing the show, like Chingy Nea’s

“The Sopranos Belongs to the Gays Now” and P. E. Moskowitz’s

“I Couldn’t Imagine Being Happy. But I Could Imagine Being Carmela.” When I asked David if he agreed with the premise that masculinity and femininity were performances, he laughed and said, “They are absolutely performing, and it is often absurd.”

David Chase is Schrödinger’s showrunner, of two minds on almost everything. Outwardly, he expresses deep gratitude for

The Sopranos’ medium-altering success, but I’ve always sensed ambivalence about the realization that it created a bottomless appetite for more

Sopranos stories, not necessarily more David Chase stories.

David has been annoyed for years by news articles and a Wikipedia entry (belatedly corrected) stating that his father changed the family’s name from DeCesare to Chase. This was especially painful for David in the early aughts, when Italian American anti-defamation activists protested

The Sopranos. Some treated the creator’s anglicized last name as evidence that he was an assimilated, sellout Italian — the kind Tony Soprano denounced as “a

medigan.” What really happened was a love story. It unfolded long before his father was born.

David Chase’s grandmother Teresa Melfi — as in

Sopranos shrink Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) — was once married to a man named DeCesare. “His real name was Guillermo or Joseph, I don’t know — let’s call him Keith,” David says dismissively. Teresa Melfi, then 29, and Keith DeCesare, who was much older, were living in Providence, Rhode Island, in the 1920s when they rented an upstairs room to a 19-year-old Italian immigrant named Joe Fusco, future killer of that poor bastard up in Buffalo. Joe and Teresa started an affair that continued in secret for years. Teresa had two children by Joe, which she passed off as her husband’s — “the fake DeCesare kids,” David calls them. These were David’s future father, Henry, and his future aunt, Evelyn. “After that, Fusco and my grandmother cleared out of Providence and took all the kids and moved to Newark and changed the name to Chase so they couldn’t be tracked,” he says.

David rarely tells that story as it occurred. But he alluded to it on the show in the subplot in which Paulie Walnuts learns that the woman he always thought was his mother was really his aunt. Paulie’s birth mother’s last words are the same ones Teresa Melfi spoke to Henry Chase, David’s father, on her deathbed: “I was a bad girl.”

I point out that he has sort of retold the story again in

The Many Saints in coded form. The movie begins with Dickie’s loathsome father, Newark mobster “Hollywood” Dick (Ray Liotta), going to Italy and bringing back a much younger bride, Giuseppina Bruno (Michela De Rossi). It’s clear she and the younger Dickie are attracted to each other, even though Dickie tries to act disinterested, and that the tension is going to cause serious problems. “What do you mean?” David says immediately when I float this theory. He thinks about it for a moment, then laughs. “Holy shit. Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah — my grandmother fucking the lodger!”

Both

The Many Saints and

The Sopranos are really David Chase stories: seriocomic generational yarns about how your family fucks you up no matter how much you love them, lean on them, and come to their aid in crisis. “What I connect to is what’s always at the heart of a

Sopranos story,” says Vera Farmiga, who plays the young version of Tony’s mother, Livia. “A nutty family filled with heated arguments and hurtful disputes, picking fights and pressing each other’s buttons, and the unconditional love that binds them together in a giant mess.” These family sagas are embellished with crime elements and therapeutic concepts as well as constant talk of the parceling and distribution of money, a vulgar ritual that David finds characteristically American and fascinating. But the heart is always the relationships between family members, biological or criminal, and how the pathologies of families and the cultures that shape them can warp sacred bonds into something nasty and sad: ground zero for the next generation’s curses and blessings.

Hamilton veteran Leslie Odom Jr., who plays Dickie’s rival Harold McBrayer, expands the word

family to include the nation, which is likewise obsessed with past glories and lineage and in denial about its crimes. Odom, who modeled his performance on his own grandfather Lenny, who migrated from South Carolina during Jim Crow looking for job opportunities, says that, to him,

The Sopranos is “about who gets to be an American, and that’s all about how you get to be in the family and what you have to do to stay in it.”

I wasn’t the one making you watch those other shows, the ones with all the scumbags! You did that to yourself!

The Dickie-centric

The Many Saints echoes the cycle of malignant parenting laid out in the series: Greek tragedy as black comedy. Nivola compares Dickie’s story to that of Oedipus Rex: The main character starts to understand his own primary role in his misfortunes, predicts a bad end for himself, and takes steps to prevent it, but the gods intervene to make sure he succumbs anyway. So too in the original: The characters are responsible for their own misery, but they also seem cursed. The hateful family matriarch, Livia (Nancy Marchand), plots filicide and nearly gets asphyxiated by her own son, a brute who subsequently almost throttles his stalkerish girlfriend, Gloria Trillo (Annabella Sciorra), who is essentially his mom reincarnated. Tony eventually asphyxiates his own surrogate son, Christopher, in a crime of opportunity following a car wreck. Even dead, Christopher is justifiably pissed at being betrayed by a surrogate father, describing Tony as “the guy I went to hell for.” Seeing Dickie’s story play out makes

The Sopranos feel like a horror movie about generational trauma replaying itself: A gangster is murdered before his young son can know him, and three decades later, that same son, who has grown up to become a gangster just like his dad, is murdered before his young daughter can know him. In David’s world, as in ours, the curse of bad parenting is forever paid forward.

The surrogate-father relationship between Dickie and young Tony is a preview of the relationship Tony will have three decades later with Chrissy. Dickie acts as an emotional sounding board for Tony and recognizes that the boy’s intelligence and dynamism marks him as a person who should have a life beyond crime; but at the same time, Dickie revels in Tony’s hero worship and basks in his appreciation after he gifts the boy high-end stereo speakers that fell off the back of a truck. It’s a mirror of adult Tony’s behavior on the series, trying to tough-love Chrissy into going into rehab and prove himself a reliable enough leader to take over the family someday, while at the same time drafting him for mob hits, body disposals, and, most harrowingly, the cover-up of the murder of his own fiancée. Chrissy, like Tony before him, is human clay, misshapen by an older adult whose pure love is poisoned by greed, ego, and rage.

I ask David if his own immediate family was ever violent like the ones depicted on

The Sopranos. He says no, not like that, but there was emotional violence from his mother, Norma, who had Livia Soprano’s knack for prying her way into people’s minds, and from his father, Henry Chase, who wasn’t a raging bull like Johnny Boy Soprano but had a temper and spanked David sometimes (“I guess these days that’s considered violence”). After the show ended, he backtracked on the easily digestible narrative he’d served up to the press in the early days, about what a miserable, destructive person his mother had been and how scarring it was growing up with her. “After some reflection, I came to the conclusion that, basically, I had a happy childhood,” he now says. When I press him on that assertion, it becomes clear he’s talking mainly about growing up middle class and educated in mid-20th-century American cities and suburbs, not about living with his mother, who “was hysterical, but she was also hysterically funny,” as he once told

60 Minutes.

“Isn’t that how it always goes, though?” he says simply when I ask if it’s possible to reconcile the contradictions. “Nothing is ever just one way.”

I’ve noticed this a bit more in the time I’ve known David — this tendency to examine things up to a point and then back away. It’s striking because although

The Sopranos expressed that sensibility in the characters it created and the stories it told, David didn’t — at least not consistently. Our conversations in the early years were more like arguments or attempts to answer a question or solve a problem. David seems increasingly inclined to let things roll off his back and then tell me another story.

During our talk in Santa Monica, David revisits one of his greatest hits, about a housepainter who lived near his hometown of North Caldwell, New Jersey, whom he calls John Pucillo — “the town idiot, in a way: addicted to every kind of fucking drug, would accost people in restaurants and interrupt rock-and-roll shows, a maniac.” If the man’s story doesn’t ring a bell for

Sopranos fans, it’s because David never told it directly (and, on the advice of his lawyer, uses a pseudonym to describe him). He took it apart like a sculptor dismantling a junker car, using the scrap for a half-dozen pieces spanning 25 years. In the 1970s, David says, Pucillo gave drugs to a young woman who was associated with a “mid-level” mobster and was subsequently whacked by a couple of young hoods who wanted to impress said mobster; they invited Pucillo to a house to estimate the cost of painting the garage, murdered him on the spot, drove the corpse to some nearby woods for burial, then abandoned Pucillo’s car in a Newark airport parking lot. A few days later, paranoid that a hiker had seen them, they went back to the woods, dug up the body, and reburied it elsewhere. They were caught and eventually confessed to the crime. This Coen-brothers-like story of delusional dimwits gave David and

The Sopranos writing staff material for multiple story arcs, including the shooting of Christopher in “Full Leather Jacket,” the near-lethal tantrum of Mustang Sally in “Another Toothpick,” and the death of Adriana in an episode titled “Long Term Parking.” David also used pieces of the Pucillo murder when he was a young writer on

The Rockford Files in the 1970s, in an episode he now describes as a “backdoor pilot” for

The Sopranos. He has been strip-mining stories of his family and former community for five decades now.

The lode is so rich it’s far from depleted. He wants to write a movie based on the story of his grandmother, the lodger, and the origin of the Chase family name. In 2012, he reteamed with HBO to make

A Ribbon of Dreams, about two men and a woman who meet on a movie set in the 1910s, sparking the creation of two entertainment-industry dynasties that span the evolution of motion pictures up to the present day (he ultimately said no because of the low budget that was offered). He and another Chase Films producer, Nicole Lambert, currently have a pilot for a series called

Strategic Service about how women flooded into the workplace during World War II. Other unproduced David stories are features or seeds of features, smaller in scale. Stuff in the filing cabinet, waiting for the light of day. Unfortunately, it appears the entertainment industry is even less interested in his pitches for intimate films about plausibly real human beings than it was when he was struggling to break into the movie business in the 1980s.

Does he think his chances of a green light would improve if he tossed some

Sopranos connections into the projects, however contrived or obligatory? “That’s not a question I really want to ask myself,” he says. During the show’s run, he batted around an idea for an episode about a Rutgers University graduate student who stops by the Soprano home to gather material for a longitudinal study and inadvertently reveals a family secret to Tony: that one of his dad’s stints in prison was really a stay in a mental hospital. Depending on how

The Many Saints does, David could picture dusting off the story of Johnny Boy Soprano’s time in a psych ward and seeing if anyone wants it, but it’s clear that it’s not a burning obsession for him right now.

I ask him if he could ever picture doing a “gangster-adjacent” show about northern New Jersey in the 1960s that used familiar characters to lure people in but was mostly about a noncrime world populated by characters from David’s notes and files. He seems flattered even one person would wish for such a show. “Do you think somebody would want to watch that?” he asks me skeptically. “Honestly?”

The Sopranoswill be forgotten, because eventually everything will be, including you and me.

It’s a shame

Not Fade Away came and went without much fanfare. The film’s lack of crime elements throws the David Chase–ness of the rest of it into sharper relief and offers a glimpse of what a world filled with Chase films and series might look like. Set in North Jersey in a time frame that overlaps with that of

The Many Saints, it’s about a Chase-like rock-and-film-loving teenager (John Magaro, who would go on to play young Silvio Dante in

The Many Saints) who gradually turns into his adult self without being cognizant of all the signposts of his development. I call it “the David Chase secret decoder ring” for understanding David’s mentality as a storyteller who likes to put unreconciled contradictions in front of audiences and let them sit with them and who is fanatically determined to avoid doing what the audience probably wants or expects. I recommend

Not Fade Away to any

Sopranos fan who insists that the cut-to-black ending of

The Sopranos can only mean “Tony got shot.”

Not Fade Away has a similarly opaque finale and includes a scene in which characters representing the young David Chase and his then-girlfriend and future wife, Denise Kelly, go to an art-house theater to watch Michelangelo Antonioni’s

Blow-Up — the head-scratcher ending of which was a major influence on

The Sopranos — and discuss how the lack of musical score in a scene makes them feel.

The Sopranos didn’t have a score either. It used needle-drop songs sparingly, and often in a Kubrick-Scorsese, pushing-against-the-drama way, because David hated how most Hollywood productions were constantly “helping” the story along. “I want people to think and feel, but I don’t want to tell people what to think or how to feel,” he once told me. It’s like the ending of

Citizen Kane: What nearly everyone thinks is the solution to the main character’s enigma is, to quote Orson Welles, “dollar-book Freud,” burning up the instant we lay eyes on it. “So it was the sled, huh,” says Adriana in an episode in which Carmela’s film club screens

Kane, ribbing the sorts of viewers who, in just a few years, would insist that the final cut-to-black could only mean one thing. “He shoulda told somebody.”

Critics took

Not Fade Away seriously, but some reviews treated it as a curiosity, an afterthought, or a kind of post-

Sopranos indulgence. There were complaints that it was too rushed, too blurry with character and incident, and too coy about letting the audience know what the story meant to the storyteller. David worries that some of the same complaints could be applied to

The Many Saints of Newark. “A lot of people said of

Not Fade Away, ‘It should’ve been a series,’ ” David says. “Some people are already saying that about

The Many Saints of Newark. I find myself reading that and thinking,

Why? Why should it have been a series? Because the story takes place over a long period of time? Because there’s too many characters? I have a screenplay I spent a year and a half on, and my agent and one other person who have read it have said it’s overwhelming, it’s too much. Too many stories. To me, it’s a story about a girl and her boyfriend.”

When you’ve created one of the greatest TV shows of all time, the criticisms are often comparisons. But David waves away my suggestion that the success of

The Sopranos was a curse as well as a blessing. “I have nothing but gratitude for the show’s success and all that it’s brought me, and to my mind, it’s all blessings,” he says. But over the years, I’ve listened raptly as he has described a film or show he’s developing, only to be disappointed along with him when the industry didn’t think it was worth funding. That’s life, of course. If

The Sopranos has taught us anything, it’s that the universe could not care less what any of us wants.

When I ask David if he thinks

The Sopranos will stand the test of time like some of the popular artworks that captured his imagination when he was starting out, he quickly says “no.” “In the end,” he says, “nothing stands the test of time. Not art, not film, not music. TV seems to have a shorter shelf life than some other art forms. Of course

The Sopranos will be forgotten, because eventually everything will be, including you and me.” He acknowledges the monumental nature of his achievement while constantly reminding us — and himself — that monuments crumble. Sometimes he sounds like Tony’s wife, Carmela (Edie Falco), in “Cold Stones,” the season-six episode in which she visits Paris with her friend Rosalie Aprile (Sharon Angela) and comes to terms with the inevitability of death and the ephemerality of her life compared with the sweep of history. “We worry so much,” she sobs. “Sometimes it feels like that’s all we do. But in the end, it just gets washed away.”

David recently relocated from New York to Santa Monica with his wife because he wants to be closer to his daughter, the actress Michele DeCesare (whom

Sopranos fans may know as Meadow’s friend Hunter Scangarelo). And also because “I just felt that New York was changing. There was scaffolding everywhere you wanted to walk. They were constantly building these new buildings that were 50 stories high. There still used to be great little bars and restaurants and great little stores that survived, selling different kinds of cheese or something. Now that’s all gone. It was all becoming a mall.”

And what can you do, really? Not much. That’s part of the human story: accepting what you have no control over and moving ahead as best you can.

By way of illustration, David tells another story, about the time that

Mad Men creator and former

Sopranos producer Matthew Weiner asked legendary TV producer Norman Lear to tell him the greatest lesson he ever learned. “Lear said, ‘The two words that came way too late in my life were ‘Over. Next,’ as in, ‘That’s over …

Next!’ And then he said, ‘Don’t wait till you’re my age to learn that.’ ”

Niggas sound mad because there wasn't enough gunplay, violence, and someone gettin' shot up in the final episode. I guess niggas was expecting a Tony Montana ending. I'm not excited or upset about the ending, it ending in a way that just makes you wonder. Shooting and violence is easy to watch, but I think David Chase made you think and wonder.

I feel duped. I don't care how creative and genius the ending may be. I didn't like it. If Tony got killed, I want to see him killed.

I feel duped. I don't care how creative and genius the ending may be. I didn't like it. If Tony got killed, I want to see him killed.