Should You Get the COVID-19 Vaccine if You Have Sickle Cell Anemia?

Meg Burke, MD

Meg Burke, MD, is a board-certified physician and medical writer. She is a practicing primary care geriatrician.

February 4, 2021, 1:55PM (PT)

Key takeaways:

Infection with COVID-19 is a new and serious threat for people with sickle cell anemia. The virus can take advantage of the weakened immune systems of people with the disease and cause devastating harm.

Luckily, there are steps that at-risk people can take to minimize their risk of infection with COVID-19. Medical advances, including vaccines and new treatment protocols, are bringing hope that we can provide more protection to people with sickle cell anemia (and other high-risk conditions) while there is still ongoing community spread of the virus.

This piece addresses the unique challenges that individuals with sickle cell anemia are facing during this pandemic and why they should prioritize getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

What is sickle cell anemia?

Sickle cell anemia (also called sickle cell disease) is a disorder of red blood cells. People are born with sickle cell anemia (you cannot catch it).

Red blood cells carry oxygen from your lungs to the rest of your body. In sickle cell anemia, the red blood cells are a different shape and size than normal red blood cells, which can lead to serious issues. With even a small problem (like not drinking enough water or getting a minor infection), people who have sickle cell anemia can feel very sick. They may require hospitalization for treatment and pain control. They can also develop complications like acute chest syndrome, which can be deadly.

Who is most likely to be diagnosed with sickle cell anemia?

Almost 100,000 people in the United States have sickle cell anemia. Most of the people diagnosed are Black or African American. About 1 in every 365 Black or African American babies born in the United States has sickle cell anemia.

Don't miss out on savings!

Get the best ways to save on your prescriptions delivered to your inbox.

By signing up, I agree to GoodRx's terms of service and privacy policy, and to receive marketing messages from GoodRx.

Are people with sickle cell anemia at a higher risk for severe COVID-19?

Yes, they are. People with sickle cell anemia who have COVID-19 infection are more likely to be hospitalized and to require intensive level care (ICU) in the hospital. They are also more likely to die from COVID-19 than people without sickle cell anemia.

One study followed 178 people with sickle cell anemia and COVID-19 infection. The average age of people in the study was less than 40 years old. Sixty-nine percent of people needed to be treated in a hospital, and 7% of them died.

Is the COVID-19 vaccine safe for people with sickle cell anemia?

Yes, the COVID-19 vaccine is safe for people with sickle cell disease.

All routine vaccines for adults and children are recommended for people with sickle cell anemia. There are studies that show that two common vaccines, the pneumococcal and influenza (“flu”) vaccines, are effective in people with sickle cell anemia. People with sickle cell anemia should be prioritized as a high-risk group to receive the yearly influenza vaccine.

There are many similarities between the COVID-19 vaccines and other vaccines that work for people with sickle cell anemia. So there is no reason to think that the COVID-19 vaccines would not be safe or effective in people with sickle cell anemia. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that people with sickle cell disease be prioritized to receive the vaccine (more on this later).

How does the COVID-19 vaccine work?

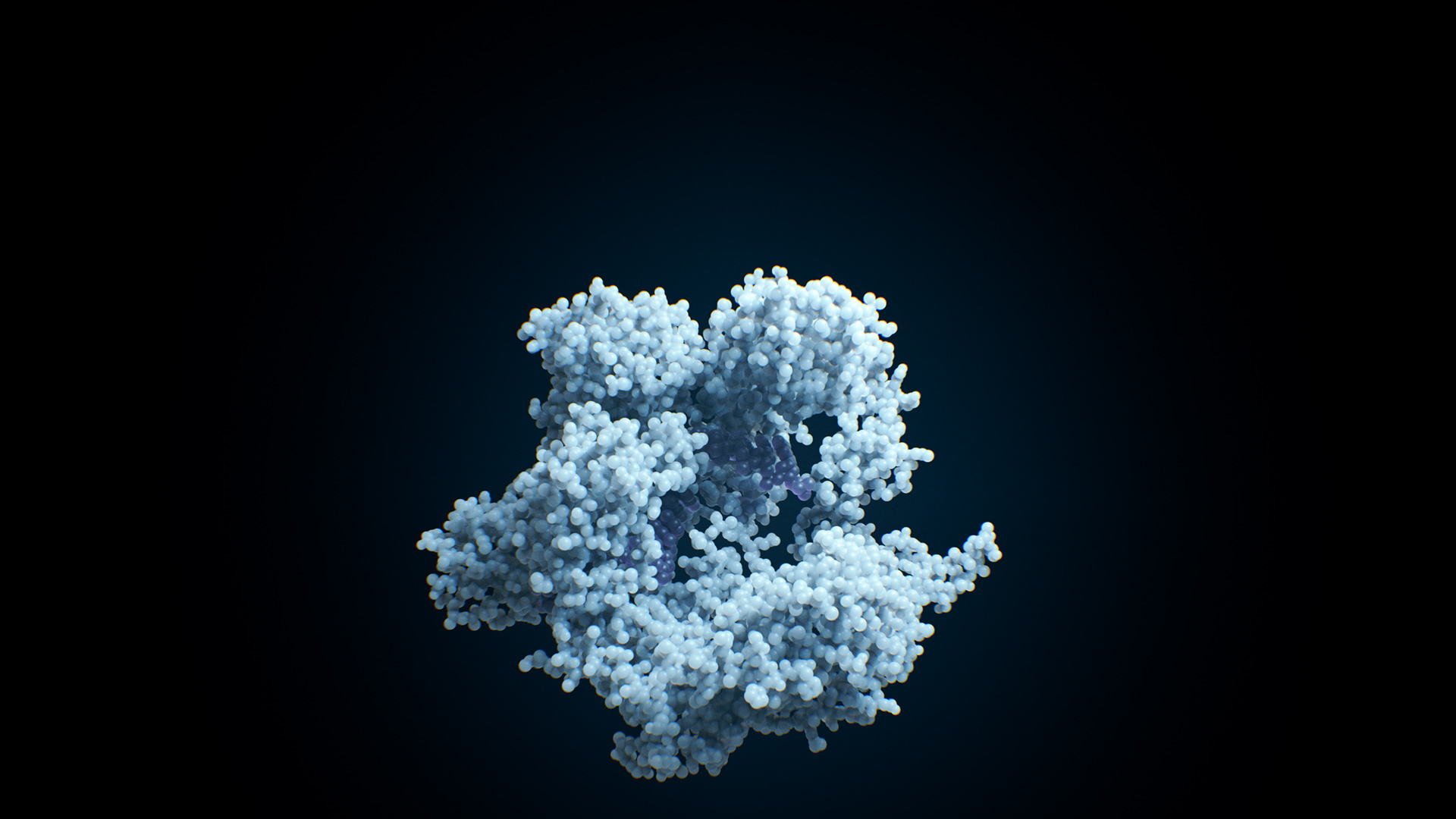

The two FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccines, Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, work by giving your cells “directions” for how to make a small piece of protein that belongs to the COVID-19 virus. Once the small piece of protein is made, your immune system (the system in your body that fights infections) recognizes this protein as something it has never seen before.

This kicks your immune system into gear to start making tools (“antibodies”) to fight off the virus. It makes a small number of antibodies after the first dose of the vaccine, and even more antibodies after the second vaccine because it is better prepared to respond to the protein.

Then, when and if you are exposed to the COVID-19 virus, your body already has the tools to fight it off and prevent you from developing symptoms and serious illness from the actual virus.

Are people with sickle cell disease considered high priority for COVID-19 vaccination?

The CDC recognizes sickle cell anemia as a condition that puts people at high risk for serious illness from COVID-19. They recommend that adults 16 to 64 years old with sickle cell anemia receive the vaccine in Phase 1c. This is after Phase 1a (healthcare providers and long-term care residents) and Phase 1b (people ≥75 years old and essential workers who are not healthcare providers). Currently in the United States, each state is deciding their priority groups for giving out the vaccine on their own.

Can the COVID-19 vaccine interact with any medications for sickle cell disease?

We don’t know the answer to this question. We do know that the most common medication used to treat sickle cell anemia, hydroxyurea, does not affect the immune response that comes from other commonly used vaccines. People on other medications that treat sickle cell anemia, such as voxelotor and crizanlizumab, should discuss their unique situation and the COVID-19 vaccine with their healthcare provider.

Other considerations for people with sickle cell disease

There are two groups of people with sickle cell disease who either are not able to receive the vaccine or must wait before they take it.

Under age 16

The current COVID-19 vaccines are not approved for anyone under age 16, including people with sickle cell anemia. There are currently active trials looking to see how safe the vaccines are and how well they work in people younger than 16 years old. Vaccine recommendations will be reconsidered once the vaccines are approved for this group.

Already had COVID-19

The approved vaccines are safe to give to people who have already had COVID-19 infection. But people who have received certain treatments, including monoclonal antibodies or convalescent plasma, should wait at least 90 days from the last day of treatment to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. This is to prevent the treatment that they received from making the vaccine less effective.

How can people with sickle cell anemia protect themselves against COVID-19 until vaccination is possible?

People with sickle cell anemia should follow all CDC guidelines to protect themselves against COVID-19 infection before they receive the vaccine. The three most important guidelines are below:

People with sickle cell anemia are at increased risk for serious COVID-19 infections. We have safe and effective vaccines that protect against COVID-19 infection. People over age 16 with sickle cell anemia should prioritize receiving their COVID-19 vaccine when it is available to them.

.

Meg Burke, MD

Meg Burke, MD, is a board-certified physician and medical writer. She is a practicing primary care geriatrician.

February 4, 2021, 1:55PM (PT)

Key takeaways:

- Sickle cell anemia can put you at increased risk of serious complications from COVID-19.

- All routine vaccines are safe, effective, and strongly recommended for people with sickle cell anemia.

- Adults and children over 16 years old with sickle cell anemia should get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Infection with COVID-19 is a new and serious threat for people with sickle cell anemia. The virus can take advantage of the weakened immune systems of people with the disease and cause devastating harm.

Luckily, there are steps that at-risk people can take to minimize their risk of infection with COVID-19. Medical advances, including vaccines and new treatment protocols, are bringing hope that we can provide more protection to people with sickle cell anemia (and other high-risk conditions) while there is still ongoing community spread of the virus.

This piece addresses the unique challenges that individuals with sickle cell anemia are facing during this pandemic and why they should prioritize getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

What is sickle cell anemia?

Sickle cell anemia (also called sickle cell disease) is a disorder of red blood cells. People are born with sickle cell anemia (you cannot catch it).

Red blood cells carry oxygen from your lungs to the rest of your body. In sickle cell anemia, the red blood cells are a different shape and size than normal red blood cells, which can lead to serious issues. With even a small problem (like not drinking enough water or getting a minor infection), people who have sickle cell anemia can feel very sick. They may require hospitalization for treatment and pain control. They can also develop complications like acute chest syndrome, which can be deadly.

Who is most likely to be diagnosed with sickle cell anemia?

Almost 100,000 people in the United States have sickle cell anemia. Most of the people diagnosed are Black or African American. About 1 in every 365 Black or African American babies born in the United States has sickle cell anemia.

Don't miss out on savings!

Get the best ways to save on your prescriptions delivered to your inbox.

By signing up, I agree to GoodRx's terms of service and privacy policy, and to receive marketing messages from GoodRx.

Are people with sickle cell anemia at a higher risk for severe COVID-19?

Yes, they are. People with sickle cell anemia who have COVID-19 infection are more likely to be hospitalized and to require intensive level care (ICU) in the hospital. They are also more likely to die from COVID-19 than people without sickle cell anemia.

One study followed 178 people with sickle cell anemia and COVID-19 infection. The average age of people in the study was less than 40 years old. Sixty-nine percent of people needed to be treated in a hospital, and 7% of them died.

Is the COVID-19 vaccine safe for people with sickle cell anemia?

Yes, the COVID-19 vaccine is safe for people with sickle cell disease.

All routine vaccines for adults and children are recommended for people with sickle cell anemia. There are studies that show that two common vaccines, the pneumococcal and influenza (“flu”) vaccines, are effective in people with sickle cell anemia. People with sickle cell anemia should be prioritized as a high-risk group to receive the yearly influenza vaccine.

There are many similarities between the COVID-19 vaccines and other vaccines that work for people with sickle cell anemia. So there is no reason to think that the COVID-19 vaccines would not be safe or effective in people with sickle cell anemia. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that people with sickle cell disease be prioritized to receive the vaccine (more on this later).

How does the COVID-19 vaccine work?

The two FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccines, Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, work by giving your cells “directions” for how to make a small piece of protein that belongs to the COVID-19 virus. Once the small piece of protein is made, your immune system (the system in your body that fights infections) recognizes this protein as something it has never seen before.

This kicks your immune system into gear to start making tools (“antibodies”) to fight off the virus. It makes a small number of antibodies after the first dose of the vaccine, and even more antibodies after the second vaccine because it is better prepared to respond to the protein.

Then, when and if you are exposed to the COVID-19 virus, your body already has the tools to fight it off and prevent you from developing symptoms and serious illness from the actual virus.

Are people with sickle cell disease considered high priority for COVID-19 vaccination?

The CDC recognizes sickle cell anemia as a condition that puts people at high risk for serious illness from COVID-19. They recommend that adults 16 to 64 years old with sickle cell anemia receive the vaccine in Phase 1c. This is after Phase 1a (healthcare providers and long-term care residents) and Phase 1b (people ≥75 years old and essential workers who are not healthcare providers). Currently in the United States, each state is deciding their priority groups for giving out the vaccine on their own.

Can the COVID-19 vaccine interact with any medications for sickle cell disease?

We don’t know the answer to this question. We do know that the most common medication used to treat sickle cell anemia, hydroxyurea, does not affect the immune response that comes from other commonly used vaccines. People on other medications that treat sickle cell anemia, such as voxelotor and crizanlizumab, should discuss their unique situation and the COVID-19 vaccine with their healthcare provider.

Other considerations for people with sickle cell disease

There are two groups of people with sickle cell disease who either are not able to receive the vaccine or must wait before they take it.

Under age 16

The current COVID-19 vaccines are not approved for anyone under age 16, including people with sickle cell anemia. There are currently active trials looking to see how safe the vaccines are and how well they work in people younger than 16 years old. Vaccine recommendations will be reconsidered once the vaccines are approved for this group.

Already had COVID-19

The approved vaccines are safe to give to people who have already had COVID-19 infection. But people who have received certain treatments, including monoclonal antibodies or convalescent plasma, should wait at least 90 days from the last day of treatment to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. This is to prevent the treatment that they received from making the vaccine less effective.

How can people with sickle cell anemia protect themselves against COVID-19 until vaccination is possible?

People with sickle cell anemia should follow all CDC guidelines to protect themselves against COVID-19 infection before they receive the vaccine. The three most important guidelines are below:

- Wear a mask that covers your mouth and nose when you are around anyone outside of your household.

- Stay distanced from other people, even when you are wearing a mask. The closest that you should get to other people is 6 feet, but farther away is better.

- Avoid any crowded spaces or unnecessary travel.

People with sickle cell anemia are at increased risk for serious COVID-19 infections. We have safe and effective vaccines that protect against COVID-19 infection. People over age 16 with sickle cell anemia should prioritize receiving their COVID-19 vaccine when it is available to them.

.