It is murder. White power brings more disease, virus, and death.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

CORONAVIRUS: HE KNEW; HE LIED; & at Least1,150,427 IN THE USA HAVE DIED - ((NEW VIRUS - NEW WARNINGS !!!))

- Thread starter QueEx

- Start date

Doctors try to untangle why they're seeing 'unprecedented' blood clotting among Covid-19 patients

CNN

By Elizabeth Cohen

Wed April 22, 2020

(CNN)Dr. Kathryn Hibbert's Covid-19 patient in the intensive care unit was not doing well. As his blood pressure plummeted, she tried to insert an intravenous line into an artery in his wrist.

A blood clot clogged the tubing.

Frustrated, Hibbert tried again with a new needle. A blood clot clogged up that line as well.

It took three tries to insert the IV.

"You just watch it clot right in front of you," said Hibbert, director of the medical intensive care unit at Massachusetts General Hospital. "It's rare to have that happen once, and extremely rare to have that happen twice."

Hibbert and other doctors are finding that some patients infected with the novel coronavirus have a propensity towards developing blood clots, which can be life threatening if the clot travels to the heart or lungs.

"The number of clotting problems I'm seeing in the ICU, all related to Covid-19, is unprecedented," Dr. Jeffrey Laurence, a hematologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, wrote in an email to CNN. "Blood clotting problems appear to be widespread in severe Covid."

Laurence and his colleagues looked at autopsies on two patients and found blood clots in the lungs and just beneath the surface of the skin, according to a study published last week. They also found blood clots beneath the skin's surface on three living patients.

In the Netherlands, a study found "remarkably high" rates of clotting among Covid patients in the ICU.

An international consortium of experts from more than 30 hospitals gathered to consider the issue. Their conclusion: It's unclear exactly why, but coronavirus patients may be predisposed to having clots.

"This is one of the most talked about questions in Covid right now," said Dr. Michelle Gong, chief of the division of critical care medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City.

At Montefiore, they've started to put all Covid-19 patients on low doses of blood thinners to prevent clots, Gong said.

Not all hospitals have taken that step -- but they're still concerned.

"It's out of the norm, and we're wondering, are blot clots one of the reasons why these patients are dying," said Dr. Todd Rice, an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

'Alarming' rates of blood clots

Being in the intensive care unit, sick and lying still, can be a perfect storm for blood clots for any patient.

"Even before Covid, we're on high alert for suspicion of clots in the ICU because they're at high risk," Gong said.

Even so, doctors have a hunch that Covid patients might be clotting even more than other ICU patients.

The Dutch study of 184 patients in the ICU with Covid-19-related pneumonia found that more than 20% were having clotting issues. A study of 81 similarly ill patients in Wuhan, China, found a 25% incidence of clots.

Dr. Behnood Bikdeli, who helped coordinate the international coalition of physicians looking into the clotting issue, called those numbers "alarming."

Bikdeli, a cardiovascular medicine fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said there are three major reasons why Covid-19 patients might have an especially high risk of clotting.

Doctors say it's hard to know exactly what's behind what they're seeing with Covid-19 patients in the ICU.

"My gut tells me there are probably a subset of Covid patients who have really abnormal clotting behavior, that this is happening more frequently than we would expect it to," said Hibbert, an instructor at Harvard Medical School.

She quickly added, though, that doctors' gut feelings are "notoriously misleading" and that studies need to be done to get to the bottom of exactly how common clotting is among coronavirus patients.

www.cnn.com

www.cnn.com

CNN

By Elizabeth Cohen

Wed April 22, 2020

(CNN)Dr. Kathryn Hibbert's Covid-19 patient in the intensive care unit was not doing well. As his blood pressure plummeted, she tried to insert an intravenous line into an artery in his wrist.

A blood clot clogged the tubing.

Frustrated, Hibbert tried again with a new needle. A blood clot clogged up that line as well.

It took three tries to insert the IV.

"You just watch it clot right in front of you," said Hibbert, director of the medical intensive care unit at Massachusetts General Hospital. "It's rare to have that happen once, and extremely rare to have that happen twice."

Hibbert and other doctors are finding that some patients infected with the novel coronavirus have a propensity towards developing blood clots, which can be life threatening if the clot travels to the heart or lungs.

"The number of clotting problems I'm seeing in the ICU, all related to Covid-19, is unprecedented," Dr. Jeffrey Laurence, a hematologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, wrote in an email to CNN. "Blood clotting problems appear to be widespread in severe Covid."

Laurence and his colleagues looked at autopsies on two patients and found blood clots in the lungs and just beneath the surface of the skin, according to a study published last week. They also found blood clots beneath the skin's surface on three living patients.

In the Netherlands, a study found "remarkably high" rates of clotting among Covid patients in the ICU.

An international consortium of experts from more than 30 hospitals gathered to consider the issue. Their conclusion: It's unclear exactly why, but coronavirus patients may be predisposed to having clots.

"This is one of the most talked about questions in Covid right now," said Dr. Michelle Gong, chief of the division of critical care medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City.

At Montefiore, they've started to put all Covid-19 patients on low doses of blood thinners to prevent clots, Gong said.

Not all hospitals have taken that step -- but they're still concerned.

"It's out of the norm, and we're wondering, are blot clots one of the reasons why these patients are dying," said Dr. Todd Rice, an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

'Alarming' rates of blood clots

Being in the intensive care unit, sick and lying still, can be a perfect storm for blood clots for any patient.

"Even before Covid, we're on high alert for suspicion of clots in the ICU because they're at high risk," Gong said.

Even so, doctors have a hunch that Covid patients might be clotting even more than other ICU patients.

The Dutch study of 184 patients in the ICU with Covid-19-related pneumonia found that more than 20% were having clotting issues. A study of 81 similarly ill patients in Wuhan, China, found a 25% incidence of clots.

Dr. Behnood Bikdeli, who helped coordinate the international coalition of physicians looking into the clotting issue, called those numbers "alarming."

Bikdeli, a cardiovascular medicine fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said there are three major reasons why Covid-19 patients might have an especially high risk of clotting.

One is that vast majority of patients who become severely ill with coronavirus have underlying medical problems, such as diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure. These patients -- whether they have coronavirus or not - have a higher tendency to clot than healthy patients.

Second, one way coronavirus can kill patients is through a "cytokine storm," where the body's own immune response turns on itself. Patients experiencing that storm, because of coronavirus, influenza, or any other reason are at a higher risk for clotting.

The third reason is that there could be something about the novel coronavirus itself that's causing clots.

Doctors say it's hard to know exactly what's behind what they're seeing with Covid-19 patients in the ICU.

"My gut tells me there are probably a subset of Covid patients who have really abnormal clotting behavior, that this is happening more frequently than we would expect it to," said Hibbert, an instructor at Harvard Medical School.

She quickly added, though, that doctors' gut feelings are "notoriously misleading" and that studies need to be done to get to the bottom of exactly how common clotting is among coronavirus patients.

Doctors try to untangle why they're seeing 'unprecedented' blood clotting among Covid-19 patients | CNN

"The number of clotting problems I'm seeing in the ICU, all related to Covid-19, is unprecedented," one New York doctor said in an email to CNN. "Blood clotting problems appear to be widespread in severe Covid."

Doctors try to untangle why they're seeing 'unprecedented' blood clotting among Covid-19 patients

Young and middle-aged people, barely sick with covid-19, are dying from strokes

Doctors sound alarm about patients in their 30s and 40s left debilitated or dead. Some didn’t even know they were infected by COVID-19.

People walk around Times Square as screens are illuminated as part of the “Light It Blue” initiative to honor health care workers, during the outbreak of the coronavirus disease in New York City on April 23, 2020. (Eduardo Munoz/Reuters)

Washington Post

By Ariana Eunjung Cha

April 24, 2020

PLEASE NOTE

The Washington Post is providing this important information about the coronavirus for free. For more free coverage of the coronavirus pandemic, sign up for our daily Coronavirus Updates newsletter where all stories are free to read.

Thomas Oxley wasn’t even on call the day he received the page to come to Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital in Manhattan. There weren’t enough doctors to treat all the emergency stroke patients, and he was needed in the operating room.

The patient’s chart appeared unremarkable at first glance. He took no medications and had no history of chronic conditions. He had been feeling fine, hanging out at home during the lockdown like the rest of the country, when suddenly, he had trouble talking and moving the right side of his body. Imaging showed a large blockage on the left side of his head.

Oxley gasped when he got to the patient’s age and covid-19 status: 44, positive.

The man was among several recent stroke patients in their 30s to 40s who were all infected with the coronavirus. The median age for that type of severe stroke is 74.

As Oxley, an interventional neurologist, began the procedure to remove the clot, he observed something he had never seen before. On the monitors, the brain typically shows up as a tangle of black squiggles — “like a can of spaghetti,” he said — that provide a map of blood vessels. A clot shows up as a blank spot.

As he used a needlelike device to pull out the clot, he saw new clots forming in real-time around it.

“This is crazy,” he remembers telling his boss.”

Stroke surge

Reports of strokes in the young and middle-aged — not just at Mount Sinai, but also in many other hospitals in communities hit hard by the novel coronavirus — are the latest twist in our evolving understanding of its connected disease, covid-19.

Even as the virus has infected nearly 2.8 million people worldwide and killed about 195,000 as of Friday, its biological mechanisms continue to elude top scientific minds. Once thought to be a pathogen that primarily attacks the lungs, it has turned out to be a much more formidable foe — impacting nearly every major organ system in the body.

Until recently, there was little hard data on strokes and covid-19.

There was one report out of Wuhan, China, that showed that some hospitalized patients had experienced strokes, with many being seriously ill and elderly. But the linkage was considered more of “a clinical hunch by a lot of really smart people,” said Sherry H-Y Chou, a University of Pittsburgh Medical Center neurologist and critical care doctor.

Now for the first time, three large U.S. medical centers are preparing to publish data on the stroke phenomenon. The numbers are small, only a few dozen per location, but they provide new insights into what the virus does to our bodies.

A stroke, which is a sudden interruption the blood supply, is a complex problem with numerous causes and presentations. It can be caused by heart problems, clogged arteries due to cholesterol, even substance abuse. Mini-strokes often don’t cause permanent damage and can resolve on their own within 24 hours. But bigger ones can be catastrophic.

The analyses suggest coronavirus patients are mostly experiencing the deadliest type of stroke. Known as large vessel occlusions, or LVOs, they can obliterate large parts of the brain responsible for movement, speech and decision-making in one blow because they are in the main blood-supplying arteries.

Many researchers suspect strokes in covid-19 patients may be a direct consequence of blood problems that are producing clots all over some people’s bodies.

Clots that form on vessel walls fly upward. One that started in the calves might migrate to the lungs, causing a blockage called a pulmonary embolism that arrests breathing — a known cause of death in covid-19 patients. Clots in or near the heart might lead to a heart attack, another common cause of death. Anything above that would probably go to the brain, leading to a stroke.

Robert Stevens, a critical care doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, called strokes “one of the most dramatic manifestations” of the blood-clotting issues. “We’ve also taken care of patients in their 30s with stroke and covid, and this was extremely surprising,” he said.

Many doctors expressed worry that as the New York City Fire Department was picking up four times as many people who died at home as normal during the peak of infection that some of the dead had suffered sudden strokes. The truth may never be known because few autopsies were conducted.

Chou said one question is whether the clotting is because of a direct attack on the blood vessels, or a “friendly-fire problem” caused by the patient’s immune response.

“In your body’s attempt to fight off the virus, does the immune response end up hurting your brain?” she asked. Chou is hoping to answer such questions through a review of strokes and other neurological complications in thousands of covid-19 patients treated at 68 medical centers in 17 countries.

Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, which operates 14 medical centers in Philadelphia, and NYU Langone Health in New York City, found that 12 of their patients treated for large blood blockages in their brains during a three-week period had the virus. Forty percent were under 50, and they had few or no risk factors. Their paper is under review by a medical journal, said Pascal Jabbour, a neurosurgeon at Thomas Jefferson.

Jabbour said many cases he has treated have unusual characteristics. Brain clots usually appear in the arteries, which carry blood away from the heart. But in covid-19 patients, he is also seeing them in the veins, which carry blood in the opposite direction and are trickier to treat. Some patients are also developing more than one large clot in their heads, which is highly unusual.

“We’ll be treating a blood vessel and it will go fine, but then the patient will have a major stroke” because of a clot in another part of the brain, he said.

The 33-year-old

At Mount Sinai, the largest medical system in New York City, physician-researcher J Mocco said the number of patients coming in with large blood blockages in their brains doubled during the three weeks of the covid-19 surge to more than 32, even as the number of other emergencies fell. More than half of were covid-19 positive.

It isn’t just the number of patients that was unusual. The first wave of the pandemic has hit the elderly and those with heart disease, diabetes, obesity or other preexisting conditions disproportionately. The covid-19 patients treated for stroke at Mount Sinai were younger and mostly without risk factors.

On average, the covid-19 stroke patients were 15 years younger than stroke patients without the virus.

“These are people among the least likely statistically to have a stroke,” Mocco said.

Mocco, who has spent his career studying strokes and how to treat them, said he was “completely shocked” by the analysis. He noted the link between covid-19 and stroke “is one of the clearest and most profound correlations I’ve come across.”

“This is much too powerful of a signal to be chance or happenstance,” he said.

In a letter to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine next week, the Mount Sinai team details five case studies of young patients who had strokes at home from March 23 to April 7. They make for difficult reading: The victims’ ages are 33, 37, 39, 44 and 49, and they were all home when they began to experience sudden symptoms, including slurred speech, confusion, drooping on one side of the face and a dead feeling in one arm.

One died, two are still hospitalized, one was released to rehabilitation, and one was released home to the care of his brother. Only one of the five, a 33-year-old woman, is able to speak.

Oxley, the interventional neurologist, said one striking aspect of the cases is how long many waited before seeking emergency care.

The 33-year-old woman was previously healthy but had a cough and headache for about a week. Over the course of 28 hours, she noticed her speech was slurred and that she was going numb and weak on her left side but, the researchers wrote, “delayed seeking emergency care due to fear of the covid-19 outbreak.”

It turned out she was already infected.

By the time she arrived at the hospital, a CT scan showed she had two clots in her brain and patchy “ground glass” in her lungs — the opacity in CT scans that is a hallmark of covid-19 infection. She was given two different types of therapy to try to break up the clots and by Day 10, she was well enough to be discharged.

Oxley said the most important thing for people to understand is that large strokes are very treatable. Doctors are often able to reopen blocked blood vessels through techniques such as pulling out clots or inserting stents. But it has to be done quickly, ideally within six hours, but no longer than 24 hours: “The message we are trying to get out is if you have have symptoms of stroke, you need to call the ambulance urgently. ”

As for the 44-year-old man Oxley was treating, doctors were able to remove the large clot that day in late March, but the patient is still struggling. As of this week, a little over a month after he arrived in the emergency room, he is still hospitalized.

13 Do's and Don'ts for Avoiding Germs at the Grocery Store:

Do wear a mask

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommend wearing masks or face coverings when going out to public settings like the grocery store or pharmacy. Try these homemade mask patterns. If you're over 60 or are immunocompromised, look into grocery stores with senior shopping hours.

Don't handle items unless you absolutely have to

How many people felt that avocado before you did? Do your best to avoid handling produce and other items while you're shopping. Make your best guess and follow the rule we set for our kids with a bowl of communal snacks: if you touch it, it's yours.

Do bring your own wipes

Grocery stores are paying special attention to store cleanliness, but they can't always keep up with every cart and handle. Bring your own disinfectant wipes to wipe down anything you need to touch like doors, carts and freezer handles.

Don't bring your family

The more people you have with you, the more likely someone will pick up a bug. And let's be honest; grocery shopping with kids is hard enough as it is. Designate one member of the family to shop or look into a grocery delivery service.

Do use electronic payment

If your store accepts Apple Pay or other types of electronic payment, use 'em. If you need to use a debit card, be sure to wipe it down with a disinfectant wipe when you get home. If you have to touch your phone to the sensor for electronic payment, wipe it down as well.

Don't ask for a receipt

Help protect yourself and your cashier by declining a paper receipt. This cuts down on the contact time and ensures that you won't have to touch each other. Some stores provide emailed receipts.

Do relax your standards for reusable bags

Reusable bags are great for the environment but also provide another surface that could transmit germs from your house to the store and vice versa. Many stores aren't allowing them now because they're often difficult to clean; choose paper at the checkout.

Don't go in without a plan

The days of lazily strolling around the grocery store until dinner inspiration hits are gone for now. Try to minimize your time out in public by walking into the grocery store with a detailed list so you can get in and get out quickly. Not sure where to start? Here are some tips for how to stock a pantry.

Do be friendly

This is a great time to give your fellow shoppers the benefit of the doubt. We're all under higher levels of stress right now, and a little kindness can go a long way. Smiling at someone who's 10 feet away won't put you at risk, and remember, we're all in this together.

Who knows? That person you smile at may be one of the shopping angels serving your community.

Don't buy ripped or damaged packages

It's important to inspect your packages of meat and prepped veggies all the time but especially now. If you notice a tear in a product, bring it to one of the store employees (wearing your mask of course) so that they can discard it.

Do have a backup plan for your ingredients

It's no surprise that many of the items on your list may be low-stock or sold out once you arrive at the store. Think through some backup options so that you can still get everything you need. If you're stocking your pantry, these creative substitutes can help.

Don't forget your own hand sanitizer

Keep a bottle of hand sanitizer in your car to use as soon as you finish grocery shopping. Most stores now provide a large bottle of hand sanitizer but everyone at the store is touching the same dispenser. Once you return home, wash your hands with soap and water.

Do wipe down your phone

Most of us use our phones to keep a grocery list or pay for our items, and it can pick up germs along the way. Be sure to clean your phone if you pulled it out at the store.

.

Do wear a mask

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommend wearing masks or face coverings when going out to public settings like the grocery store or pharmacy. Try these homemade mask patterns. If you're over 60 or are immunocompromised, look into grocery stores with senior shopping hours.

Don't handle items unless you absolutely have to

How many people felt that avocado before you did? Do your best to avoid handling produce and other items while you're shopping. Make your best guess and follow the rule we set for our kids with a bowl of communal snacks: if you touch it, it's yours.

Do bring your own wipes

Grocery stores are paying special attention to store cleanliness, but they can't always keep up with every cart and handle. Bring your own disinfectant wipes to wipe down anything you need to touch like doors, carts and freezer handles.

Don't bring your family

The more people you have with you, the more likely someone will pick up a bug. And let's be honest; grocery shopping with kids is hard enough as it is. Designate one member of the family to shop or look into a grocery delivery service.

Do use electronic payment

If your store accepts Apple Pay or other types of electronic payment, use 'em. If you need to use a debit card, be sure to wipe it down with a disinfectant wipe when you get home. If you have to touch your phone to the sensor for electronic payment, wipe it down as well.

Don't ask for a receipt

Help protect yourself and your cashier by declining a paper receipt. This cuts down on the contact time and ensures that you won't have to touch each other. Some stores provide emailed receipts.

Do relax your standards for reusable bags

Reusable bags are great for the environment but also provide another surface that could transmit germs from your house to the store and vice versa. Many stores aren't allowing them now because they're often difficult to clean; choose paper at the checkout.

Don't go in without a plan

The days of lazily strolling around the grocery store until dinner inspiration hits are gone for now. Try to minimize your time out in public by walking into the grocery store with a detailed list so you can get in and get out quickly. Not sure where to start? Here are some tips for how to stock a pantry.

Do be friendly

This is a great time to give your fellow shoppers the benefit of the doubt. We're all under higher levels of stress right now, and a little kindness can go a long way. Smiling at someone who's 10 feet away won't put you at risk, and remember, we're all in this together.

Who knows? That person you smile at may be one of the shopping angels serving your community.

Don't buy ripped or damaged packages

It's important to inspect your packages of meat and prepped veggies all the time but especially now. If you notice a tear in a product, bring it to one of the store employees (wearing your mask of course) so that they can discard it.

Do have a backup plan for your ingredients

It's no surprise that many of the items on your list may be low-stock or sold out once you arrive at the store. Think through some backup options so that you can still get everything you need. If you're stocking your pantry, these creative substitutes can help.

Don't forget your own hand sanitizer

Keep a bottle of hand sanitizer in your car to use as soon as you finish grocery shopping. Most stores now provide a large bottle of hand sanitizer but everyone at the store is touching the same dispenser. Once you return home, wash your hands with soap and water.

Do wipe down your phone

Most of us use our phones to keep a grocery list or pay for our items, and it can pick up germs along the way. Be sure to clean your phone if you pulled it out at the store.

.

NY Times Gets Destroyed For Absolutely Unbelievable Trump Disinfectant Tweet: 'Some Experts Say...'

Blue-Check Twitter savaged The New York Times over a tweet and an article that carried the mind-boggling suggestion that only "some experts" believe that President Donald Trump's suggestions about the internal consumption of disinfectant are dangerous.

Why the Coronavirus Is So Confusing

A guide to making sense of a problem that is now too big for any one person to fully comprehend

Why the Coronavirus Is So Confusing

A guide to making sense of a problem that is now too big for any one person to fully comprehend

Should You Get an Antibody Test?

A user’s guide to the immune system

JAMES HAMBLINMAY 1, 2020

GETTY / THE ATLANTIC

The road to ending social distancing is less contentious than it may seem. Many priorities are clear: Invest in comprehensive testing for the coronavirus, in effectively treating the disease, and in vaccine development and production. Invest in research to understand transmission of the virus, and precisely how to prevent it.

The fundamental mystery to solve is how people develop immunity, the key to which will be testing for antibodies in the blood. Identifying antibodies will help inform contact tracing; determine the effectiveness of vaccines; and clarify who may be susceptible to re-infection, and at what point, and why.

Antibody tests (sometimes referred to as serology) have begun rolling out across the country, to much fanfare. Last week, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced an “aggressive” deployment of tests—and early numbers have suggested that about 15 percent of people in the state have antibodies to the coronavirus. Some pundits and armchair immunologists have implied that high rates of antibodies mean that cities could reopen quickly. Some take the apparently high number of asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 to mean the disease is not that bad, and that social-distancing measures have proved to be an overreaction.

This is false hope, going beyond what science can yet say. The basics of immunity—mechanisms most of us haven’t thought about since high-school biology, if ever—have suddenly been politicized to the point that they seem much more confusing than they actually are.

So I thought a basic FAQ might be of use.

What is serology?

The study of serum. It mainly involves adding sero to the beginning of words (seroprevalence, seropositivity, seroprotection). These words are going to be a part of our lives for the next year or two, and they may sound technical, but basically all you have to do is subtract sero to understand them. Prefixes like that are a trick that doctors use to sound smart and justify our student loans, but basically it means “we’re talking about antibodies.”

What does it mean if I have antibodies?

If you have antibodies to any virus, it means you’ve been exposed to that virus (or a vaccine for it). Your body remembers that exposure and will recognize the virus if you get exposed again. But having antibodies doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be able to fight off a second infection. For that, you need sufficient numbers of antibodies, and they need to be effective antibodies. We don’t yet know the degree to which people with coronavirus antibodies are protected from getting COVID-19 a second or third time.

Do antibodies kill the virus?

Antibodies are proteins that float around in your blood and, essentially, look for things that are not right. If a virus has invaded and hijacked your cells to make thousands of clone viruses, for example, that’s not right. But the abnormality can be tricky to identify, because viruses can hide within our own cells. When a new, unknown invader proves difficult to distinguish, the body sometimes gets desperate and calls out the entire immune-system military—and also the National Guard, and the Boy Scouts, and anyone who has a pitchfork or a torch. The process can be fatal. Antibodies help prevent this by detecting the virus, or virus-infected cells, and binding to their surfaces, signaling the immune system to destroy only them. This allows for a precise, targeted killing that doesn’t do too much harm to healthy organs. The next time we see the virus, essentially, we just send out the Navy SEALs.

Will everyone develop antibodies?

Most humans have antibodies to the four coronaviruses that cause common colds, and it’s expected that antibodies to the new coronavirus will reliably develop in most people who are exposed to it. The question is how long they will last, and how consistently they’ll be effective at preventing a second case of the disease (if they are effective, they’ll be considered “neutralizing antibodies”). Typically you start producing some antibodies shortly after getting a virus. One kind, known as IgG, has reliably shown up on antibody tests in the second week of a COVID-19 infection. If this coronavirus is like other coronaviruses, another kind of antibody, known as IgM, will show up around the same time. The as-yet unanswered question is how long they will stick around.

How long do antibodies last?

We don’t know, but other coronavirus antibodies tend to last a few years. After the SARS coronavirus outbreak, in 2001, one study found that only 9 percent of people had antibodies six years after getting sick. They take time to develop, and they form only after you’ve been exposed to the virus. They are your blood’s unconscious memory of past infections. With most viral outbreaks, at least some of us have some degree of prior exposure—and, therefore, protection. But none of our immune systems has that memory this time around.

Do I have to get sick from the coronavirus to get antibodies?

No. This is the principle behind vaccination, whereby we try to create a situation that exposes you to enough of a virus that you develop antibodies, but not enough that you get sick. But it’s not clear that every exposure to the coronavirus will lead to antibodies. Though the amount of the virus that people are exposed to does seem to affect how sick they get, we don’t yet know how much the virus needs to replicate inside you before you develop antibodies.

How reliably do antibodies fight off the coronavirus?

This is the central question to answer in the coming months. Usually antibodies work very reliably, but in some cases they barely help, and in certain diseases having some antibodies is worse than having none. This is known as immune enhancement, a phenomenon that may or may not prove relevant with this coronavirus; it is worth keeping in mind when people suggest that antibody tests are currently painting a clear picture of who is totally protected from the disease.

Can I use someone else’s antibodies?

There is a lot of hope that this could be a useful treatment for people who get sick from COVID-19, or for very high-risk people who get exposed to the virus. We inject people with antibodies to prevent diseases like tetanus, so the idea isn’t unprecedented. Those antibodies instantly help neutralize the toxins in your blood after you step on a rusty nail, so you don’t have to endure two weeks of severe muscle spasms and lockjaw while your body makes its own. The approach is being studied now for this coronavirus; Tom Hanks even donated some of his antibody-laden plasma to the cause. But injected antibodies don’t stay with us long. For lasting protection, you need to make your own antibodies.

Should I get an antibody test right now?

I would recommend it, but only if you’re part of a research study where your results are contributing to an understanding of what results actually mean. Otherwise, it’s generally not advisable to get tests unless we know what to do with the results, and we don’t yet. We don’t even know if most of the tests that have come on the market are accurate. There are now more than 150 tests, most of which have not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Why does FDA approval matter?

The FDA is maybe best known for its role in helping make sure that drugs are safe and effective before they go to market. But the FDA does the same for tests, too. That includes nasal-swab tests to detect the coronavirus during an infection, and blood tests to detect antibodies after an infection. The approval process slows down the availability of tests, but the idea is that patients and doctors should have some assurance that the tests they’re using are at least somewhat accurate. Even the coronavirus antibody tests that are “approved” right now by the FDA are only being used under a special “emergency use authorization,” for which standards are looser than usual. The others could be total scams. You can sell almost anything and call it a coronavirus antibody test right now; the market is operating mostly on an honor system.

What makes one antibody test better than another?

The two key features are sensitivity and specificity. A test has to be sensitive enough not to miss the antibodies if they’re actually present, but specific enough not to accidentally show a positive result.

How could a test be positive if I don’t have antibodies?

These tests work like magnets that attract antibodies, trying to pull them out of a small sample of blood. But the magnet needs to be precise. When it’s not, other antibodies could stick to it, and you could get a false positive result. This is one of the things that is typically vetted during the FDA approval process. False positives could compromise a test’s ability to guide life-and-death decisions about how to reopen society.

Can a test say whether I have enough antibodies to be protected?

This is measured in a specific type of antibody test known as a titer, which doesn’t just determine whether you have antibodies but counts the number in your blood. So the key questions will be what level is adequate to confer immunity, and under what conditions do people develop that adequate level? How reliably can we assume that if you have any antibodies, you are immune? That would mean you’re not only seropositive but seroprotected.

Why are we putting so much emphasis on antibody testing if the results don’t necessarily mean I’m superhuman?

Right now, the antibody tests are being used to help map out where the coronavirus has spread, like tracking the footprints it has left. Combined with other types of research, this information will eventually help identify who is most susceptible to infection, and why. Even if we can’t tell individuals that they are totally protected, we could theoretically begin to allocate scarce resources away from a city where 50 percent of people have antibodies to one where only 5 percent of people do.

That means if we have a lot of positive antibody tests, we can stop social distancing?

One day, yes, hopefully. But the tests aren’t good enough yet, and we don’t know how many people with antibodies are truly protected from the coronavirus. Antibodies wane over time, and not everyone has the same, lasting response to disease or vaccination—as we’ve seen with diseases like measles and hepatitis B. We don’t know how reliably people who are infected by the coronavirus develop effective antibodies. Figuring that out requires longer-term studies of who gets sick twice, and what sort of antibody response is needed to prevent that.

What percentage of people would need to have antibodies—effective ones, in effective amounts—to completely reopen society?

That comes down to the concept of herd immunity. With a disease like measles, not everyone has complete immunity by way of vaccination (because people’s antibody response to the vaccine waned over time, or because they have refused vaccination in the first place). But except for occasional, local outbreaks, we still collectively have enough antibodies that the virus can’t take hold and cause a pandemic. In the same way, the annual flu season ends as we approach herd immunity to that year’s strain of influenza.

The percentage of people required to reach herd immunity varies based on the virus. For a more contagious virus, we need higher percentages of the population to be immune. Determining that percentage comes down to the “basic reproductive number,” or R0, which is the average number of people who will catch a disease from any given contagious person. There’s still disagreement about what that number is for the new coronavirus, but at the moment many experts estimate that it’s between two and three. In any case, one basic approximation of herd immunity is when you multiply the R0 by the proportion of the population that is not immune and the result is less than one.

Does all the mask-wearing and social distancing mean we’re going to take longer to get to herd immunity?

Those basic measures can and have helped to lower the R0. If we keep doing them, we could have a relatively low percentage of immune people and still open businesses back up, because the disease would effectively be less contagious. People would get COVID-19, but we wouldn’t be flirting with catastrophic exponential growth.

What’s the best estimate for the percentage of immune people across the United States right now?

Given the caveat I keep repeating—that it’s truly impossible to say—the best guesses are all in the single digits. The rate of positive antibody tests varies widely from place to place. And those tests are limited and we don’t know what they mean. In Chelsea, Massachusetts, a small, early study appeared to show a roughly 30 percent positive rate, while in Santa Clara County, California, the positive rate was about 3 percent. In either case, there’s no evidence that we are near herd immunity. And, again, these studies weren’t meant to measure immunity; they were only meant to measure exposure. Measuring immunity will mean seeing how many of the people with antibodies end up getting sick again.

Should we give up for now on coronavirus antibody tests? I’ve lost hope.

No, this is how immunity works in most infectious diseases—it involves uncertainty. There are always questions about exactly how many antibodies are required to prevent an infection, and how long they last. We act based on averages and best estimates across populations. But at an individual level, none of us is suddenly rendered invincible. We may only ever be able to say that, for example, 80 percent of people who have a positive coronavirus antibody test are truly adequately protected. But when the prevalence of disease falls—because so many of us have been sick, or get vaccinated, or simply practice good hygiene—that number becomes enough to effectively protect us. In keeping with the recurring theme of this pandemic, we’re all in this together.

JAMES HAMBLIN, M.D., is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He is also a lecturer at Yale School of Public Health and author of the forthcoming book Clean.

Seriously, how STUPID do they think Americans are?

From the New York Times: "As President Trump presses states to reopen their economies, his administration is privately projecting a steady rise in coronavirus infections and deaths over the next several weeks, reaching about 3,000 daily deaths on June 1 — nearly double the current level."

Read more: https://nyti.ms/2WptTx3

From the New York Times: "As President Trump presses states to reopen their economies, his administration is privately projecting a steady rise in coronavirus infections and deaths over the next several weeks, reaching about 3,000 daily deaths on June 1 — nearly double the current level."

Read more: https://nyti.ms/2WptTx3

Seriously, how STUPID do they think Americans are?

Thousands of deaths a day stupid ???

.

Mute

Trump’s Press Sec called out for saying Trump would NEVER let COVID enter US

Health

The 7 Most Dangerous Spots You Can Catch Coronavirus

THE CURVE MAY BE FLATTENING, BUT THERE ARE STILL HIGH RISK LOCATIONS WHERE COVID LURKS.

By COLBY HALL

MAY 2, 2020

iStock

iStock

Stay-at-home guidelines might be lifting in a few places, but a number of states are still seeing an increase in coronavirus cases. Even if you're thoroughly washing your hands, maintaining six feet of distance from others, and scrubbing your surfaces daily, the fact is that your risk of contracting COVID-19 is still significant.

There are a number of everyday locations that pose a particularly high risk of contracting the potentially deadly virus. Here are the places that could increase your odds of contracting COVID-19. And for more risks to avoid right now, check out 10 Health Risks You Can't Afford to Take Amid the Coronavirus.

1. Inside an elevator

The COVID-19 contagion can not only live on metal surfaces for three days, according to research from the National Institutes of Health, but it can also live in aerosol form for up to three hours. So poorly ventilated, crowded, confined spaces—like elevators—are a COVID-19 outbreak waiting to happen. Even if you're riding in an empty elevator, you're exposed to air that could have been coughed in or sneezed in by infected individuals just before you. That is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests all individuals should wear masks outside of their homes. And if you want to make your own mask, check out The 7 Best Materials for Making Your Own Face Mask, Backed by Science.

2. At the grocery store checkout counter

Grocery store clerks are not only on the frontlines of the battle against this pandemic, but many are actually dying after contracting the virus, due to frequent exposure. It turns out that the one place in the grocery store where people are most at risk of contracting COVID-19 is the checkout counter, according to a recent CNN report. So wear gloves and a mask at the grocery store and keep your distance from others, including the staff.

3. Riding on airplanes

As we previously mentioned, the conditions most conducive to the spread of COVID-19 are unventilated and crowded spaces. A recent study out of Japan, from the country's National Institute of Infectious Diseases, found that the odds that a primary case of COVID-19 was transmitted in a closed environment was nearly 19 times greater compared to an open-air environment. The research has not yet been peer-reviewed, but we can all agree that there is no space more confined than an airplane. Flying has almost always come with the worry of catching someone else's germs, and the same concern holds true for the coronavirus. And for more ways air travel is changing amid the pandemic, check out 13 Things You May Never See on Airplanes Again After Coronavirus.

4. Taking crowded subways and buses

Speaking of confined spaces and travel, mass transit systems lead the league in variables friendly to spreading germs. In fact, a 2011 study published in the journal BMC Infectious Diseases showed that those who took mass transit were six times more likely to contract a respiratory illness than those who didn't. Wearing masks and gloves goes a long way in helping you avoid contracting COVID-19 or any contagion, but if you can avoid the buses, subways, and trains, please do. And for more ways mass transit is changing, check out 8 Things You May Never See on Public Transit Again After Coronavirus.

5. Going to a public restrooms

If you are venturing outside of your home, please be sure to use your bathroom before heading out the door. Public bathrooms are another place you want to avoid amid the pandemic, seeing as COVID-19 can easily be spread via oral-fecal transmission and some of the earliest coronavirus symptoms appear to be gastrointestinal.

6. Visiting hospitals

Hear us out on this one. According to recent research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the concentration of the coronavirus lends itself to it being more contagious. So, similar to the situation with grocery store clerks, being exposed more often to COVID-19 increases your risk of getting it. The reason why health officials are warning the public to avoid hospitals unless absolutely necessary is twofold: 1) It avoids overloading hospitals so that health care workers are in a position to treat the severely ill, and 2) It helps you avoid getting infected if you do not have COVID-19.

7. Staying too close to a family member with COVID-19

A recent study out of China, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, looked at 318 COVID-19 outbreaks in the country in which there were three or more cases identified. The researchers found that homes were "the dominant category," with 254 of the 318 outbreaks stemming from houses. (The other categories were transport, food, entertainment, shopping, and "other.") So if a roommate or family member in your home has COVID-19 symptoms and/or tests positive, be sure that they're isolating themselves from everyone else.

.

And for more COVID-19 info to know, check out 25 Coronavirus Facts You Should Know by Now.

The 7 Most Dangerous Spots You Can Catch Coronavirus

THE CURVE MAY BE FLATTENING, BUT THERE ARE STILL HIGH RISK LOCATIONS WHERE COVID LURKS.

By COLBY HALL

MAY 2, 2020

Stay-at-home guidelines might be lifting in a few places, but a number of states are still seeing an increase in coronavirus cases. Even if you're thoroughly washing your hands, maintaining six feet of distance from others, and scrubbing your surfaces daily, the fact is that your risk of contracting COVID-19 is still significant.

There are a number of everyday locations that pose a particularly high risk of contracting the potentially deadly virus. Here are the places that could increase your odds of contracting COVID-19. And for more risks to avoid right now, check out 10 Health Risks You Can't Afford to Take Amid the Coronavirus.

1. Inside an elevator

The COVID-19 contagion can not only live on metal surfaces for three days, according to research from the National Institutes of Health, but it can also live in aerosol form for up to three hours. So poorly ventilated, crowded, confined spaces—like elevators—are a COVID-19 outbreak waiting to happen. Even if you're riding in an empty elevator, you're exposed to air that could have been coughed in or sneezed in by infected individuals just before you. That is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests all individuals should wear masks outside of their homes. And if you want to make your own mask, check out The 7 Best Materials for Making Your Own Face Mask, Backed by Science.

2. At the grocery store checkout counter

Grocery store clerks are not only on the frontlines of the battle against this pandemic, but many are actually dying after contracting the virus, due to frequent exposure. It turns out that the one place in the grocery store where people are most at risk of contracting COVID-19 is the checkout counter, according to a recent CNN report. So wear gloves and a mask at the grocery store and keep your distance from others, including the staff.

3. Riding on airplanes

As we previously mentioned, the conditions most conducive to the spread of COVID-19 are unventilated and crowded spaces. A recent study out of Japan, from the country's National Institute of Infectious Diseases, found that the odds that a primary case of COVID-19 was transmitted in a closed environment was nearly 19 times greater compared to an open-air environment. The research has not yet been peer-reviewed, but we can all agree that there is no space more confined than an airplane. Flying has almost always come with the worry of catching someone else's germs, and the same concern holds true for the coronavirus. And for more ways air travel is changing amid the pandemic, check out 13 Things You May Never See on Airplanes Again After Coronavirus.

4. Taking crowded subways and buses

Speaking of confined spaces and travel, mass transit systems lead the league in variables friendly to spreading germs. In fact, a 2011 study published in the journal BMC Infectious Diseases showed that those who took mass transit were six times more likely to contract a respiratory illness than those who didn't. Wearing masks and gloves goes a long way in helping you avoid contracting COVID-19 or any contagion, but if you can avoid the buses, subways, and trains, please do. And for more ways mass transit is changing, check out 8 Things You May Never See on Public Transit Again After Coronavirus.

5. Going to a public restrooms

If you are venturing outside of your home, please be sure to use your bathroom before heading out the door. Public bathrooms are another place you want to avoid amid the pandemic, seeing as COVID-19 can easily be spread via oral-fecal transmission and some of the earliest coronavirus symptoms appear to be gastrointestinal.

6. Visiting hospitals

Hear us out on this one. According to recent research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the concentration of the coronavirus lends itself to it being more contagious. So, similar to the situation with grocery store clerks, being exposed more often to COVID-19 increases your risk of getting it. The reason why health officials are warning the public to avoid hospitals unless absolutely necessary is twofold: 1) It avoids overloading hospitals so that health care workers are in a position to treat the severely ill, and 2) It helps you avoid getting infected if you do not have COVID-19.

7. Staying too close to a family member with COVID-19

A recent study out of China, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, looked at 318 COVID-19 outbreaks in the country in which there were three or more cases identified. The researchers found that homes were "the dominant category," with 254 of the 318 outbreaks stemming from houses. (The other categories were transport, food, entertainment, shopping, and "other.") So if a roommate or family member in your home has COVID-19 symptoms and/or tests positive, be sure that they're isolating themselves from everyone else.

.

And for more COVID-19 info to know, check out 25 Coronavirus Facts You Should Know by Now.

COVID-19 is now believed to attack kids, kidneys, hearts, and nerves, not just lungs

May 11, 2020

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) saidSunday that three New York children have died and 73 have become gravely ill with an inflammatory disease tied to COVID-19. The illness, pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, has symptoms similar to toxic shock or Kawasaki disease. Two of the children who died were of elementary school age, the third was an adolescent, and they were from three separate counties and had no known underlying health issues, said New York health commissioner Dr. Howard Zucker. Cases have been reported in several other states.

New York City health officials warned about the disease last week, but health providers were alerted on May 1 after hearing of reports from Britain, The New York Times reports. Symptoms have included prolonged high fever, racing hearts, rash, and severe abdominal pain. Dr. David Reich, president of Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, said the five cases his hospital treated started with gastrointestinal issues and progressed to very low blood pressure, expanded blood pressure, and in some cases, heart failure. "We were all thinking this is a disease that kills old people, not kids," he told The Washington Post. Cuomo made a similar point.

It isn't just children struggling with arterial inflammation. In fact, for a virus originally believed to primarily destroy the lungs, COVID-19 also "attacks the heart, weakening its muscles and disrupting its critical rhythm," the Postreports. "It savages kidneys so badly some hospitals have run short of dialysis equipment. It crawls along the nervous system, destroying taste and smell and occasionally reaching the brain. It creates blood clots that can kill with sudden efficiency."

Many scientists now believe coronavirus wreaks havoc in the body through some combination of an attack on blood vessels, possibly the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels, and "cytokine storms," when the immune system goes haywire. "Our hypothesis is that COVID-19 begins as a respiratory virus and kills as a cardiovascular virus," Dr. Mandeep Mehra at Harvard Medical School tells the Post.

Read more about the different ways COVID-19 attacks the body at The Washington Post. Peter Weber

May 11, 2020

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) saidSunday that three New York children have died and 73 have become gravely ill with an inflammatory disease tied to COVID-19. The illness, pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, has symptoms similar to toxic shock or Kawasaki disease. Two of the children who died were of elementary school age, the third was an adolescent, and they were from three separate counties and had no known underlying health issues, said New York health commissioner Dr. Howard Zucker. Cases have been reported in several other states.

New York City health officials warned about the disease last week, but health providers were alerted on May 1 after hearing of reports from Britain, The New York Times reports. Symptoms have included prolonged high fever, racing hearts, rash, and severe abdominal pain. Dr. David Reich, president of Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, said the five cases his hospital treated started with gastrointestinal issues and progressed to very low blood pressure, expanded blood pressure, and in some cases, heart failure. "We were all thinking this is a disease that kills old people, not kids," he told The Washington Post. Cuomo made a similar point.

It isn't just children struggling with arterial inflammation. In fact, for a virus originally believed to primarily destroy the lungs, COVID-19 also "attacks the heart, weakening its muscles and disrupting its critical rhythm," the Postreports. "It savages kidneys so badly some hospitals have run short of dialysis equipment. It crawls along the nervous system, destroying taste and smell and occasionally reaching the brain. It creates blood clots that can kill with sudden efficiency."

Many scientists now believe coronavirus wreaks havoc in the body through some combination of an attack on blood vessels, possibly the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels, and "cytokine storms," when the immune system goes haywire. "Our hypothesis is that COVID-19 begins as a respiratory virus and kills as a cardiovascular virus," Dr. Mandeep Mehra at Harvard Medical School tells the Post.

Read more about the different ways COVID-19 attacks the body at The Washington Post. Peter Weber

‘I give advice according to the best scientific evidence’ — Watch Dr. Fauci clap back at Sen. Rand Paul for doubting his COVID-19 expertise and suggesting kids go back to school

via NowThis Politics

via NowThis Politics

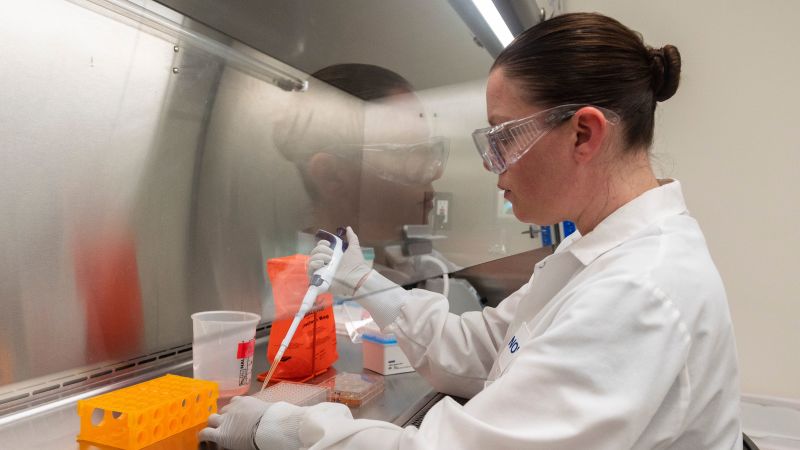

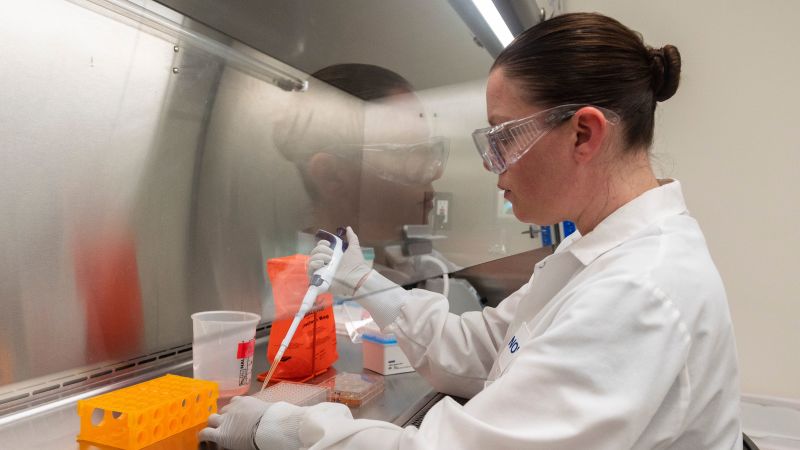

Early results from Moderna coronavirus vaccine trial show participants developed antibodies against the virus

CNN

By Elizabeth Cohen, Senior Medical Correspondent

Mon May 18, 202

(CNN) Study subjects who received Moderna's Covid-19 vaccine had positive early results, according to the biotech company, which partnered with the National Institutes of Health to develop the vaccine.

If future studies go well, the company's vaccine could be available to the public as early as January, Dr. Tal Zaks, Moderna's chief medical officer, told CNN.

"This is absolutely good news and news that we think many have been waiting for for quite some time," Zaks said.

These early data come from the Phase 1 clinical trial, which typically studies a small number of people and focuses on whether a vaccine is safe and elicits an immune response.

The results of the study, which was led by the National Institutes Health, have not been peer reviewed or published in a medical journal.

Moderna, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is one of eight developers worldwide doing human clinical trials with a vaccine against the novel coronavirus, according to the World Health Organization. Two others, Pfizer and Inovio, are also in the United States, one is at the University of Oxford in Britain, and four are in China.

Moderna has vaccinated dozens of study participants and measured antibodies in eight of them. All eight developed neutralizing antibodies to the virus at levels reaching or exceeding the levels seen in people who've naturally recovered from Covid-19, according to the company.

Neutralizing antibodies bind to the virus, disabling it from attacking human cells.

"We've demonstrated that these antibodies, this immune response, can actually block the virus," Zaks said. "I think this is a very important first step in our journey towards having a vaccine."

A vaccine specialist who is not involved in Moderna's work said the company's results are "great."

"It shows that not only did the antibody bind to the virus, but it prevented the virus from infecting the cells," said Dr. Paul Offit, a member of the NIH panel that's setting a framework for vaccine studies in the US.

While the vaccine had promising results in the lab, it's not known if it will protect people in the real world. The US Food and Drug Administration has cleared the company to begin Phase 2 trials, which typically involve several hundred of people, and Moderna plans to start large-scale clinical trials, known as Phase 3 trials, in July, which typically involve tens of thousands of people.

Offit said before the pandemic, vaccine developers would typically test out their product in thousands of people before moving on to Phase 3, but that Moderna is "extremely unlikely" to have vaccinated that many by July, since they've only vaccinated dozens so far.

He said it makes sense to Moderna to move into Phase 3 without vaccinating that many people, given that Covid-19 is killing thousands of people each day.

"This is a different time," Offit said.

In January, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases, said it would take about 12 to 18 months to get a vaccine on the market. Zaks said he agreed with that estimate for Moderna's vaccine, putting a delivery date somewhere between January and June of next year.

In the Moderna study, three participants developed fever and other flu-like symptoms when they received the vaccine at a dose of 250 micrograms. Moderna anticipates the Phase 3 study on dosage will be between 25 and 100 micrograms.

So far, the Moderna study subjects who were vaccinated even at 25 and 100 micrograms achieved antibody levels similar to or even higher than people who naturally became infected with coronavirus.

But it's not clear whether natural infection confers immunity to re-infection, and so similarly it's not clear whether vaccination confers immunity.

"That's a good question, and the truth is, we don't know that yet," Zaks said. "We are going to have to conduct formal efficacy trials where you vaccinate many, many people, and then you monitor them in the ensuing months to make sure they don't get sick."

CNN's Devon Sayers contributed to this report.

www.cnn.com

www.cnn.com

.

CNN

By Elizabeth Cohen, Senior Medical Correspondent

Mon May 18, 202

(CNN) Study subjects who received Moderna's Covid-19 vaccine had positive early results, according to the biotech company, which partnered with the National Institutes of Health to develop the vaccine.

If future studies go well, the company's vaccine could be available to the public as early as January, Dr. Tal Zaks, Moderna's chief medical officer, told CNN.

"This is absolutely good news and news that we think many have been waiting for for quite some time," Zaks said.

These early data come from the Phase 1 clinical trial, which typically studies a small number of people and focuses on whether a vaccine is safe and elicits an immune response.

The results of the study, which was led by the National Institutes Health, have not been peer reviewed or published in a medical journal.

Moderna, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is one of eight developers worldwide doing human clinical trials with a vaccine against the novel coronavirus, according to the World Health Organization. Two others, Pfizer and Inovio, are also in the United States, one is at the University of Oxford in Britain, and four are in China.

Moderna has vaccinated dozens of study participants and measured antibodies in eight of them. All eight developed neutralizing antibodies to the virus at levels reaching or exceeding the levels seen in people who've naturally recovered from Covid-19, according to the company.

Neutralizing antibodies bind to the virus, disabling it from attacking human cells.

"We've demonstrated that these antibodies, this immune response, can actually block the virus," Zaks said. "I think this is a very important first step in our journey towards having a vaccine."

A vaccine specialist who is not involved in Moderna's work said the company's results are "great."

"It shows that not only did the antibody bind to the virus, but it prevented the virus from infecting the cells," said Dr. Paul Offit, a member of the NIH panel that's setting a framework for vaccine studies in the US.

While the vaccine had promising results in the lab, it's not known if it will protect people in the real world. The US Food and Drug Administration has cleared the company to begin Phase 2 trials, which typically involve several hundred of people, and Moderna plans to start large-scale clinical trials, known as Phase 3 trials, in July, which typically involve tens of thousands of people.

Offit said before the pandemic, vaccine developers would typically test out their product in thousands of people before moving on to Phase 3, but that Moderna is "extremely unlikely" to have vaccinated that many by July, since they've only vaccinated dozens so far.

He said it makes sense to Moderna to move into Phase 3 without vaccinating that many people, given that Covid-19 is killing thousands of people each day.

"This is a different time," Offit said.

In January, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases, said it would take about 12 to 18 months to get a vaccine on the market. Zaks said he agreed with that estimate for Moderna's vaccine, putting a delivery date somewhere between January and June of next year.

In the Moderna study, three participants developed fever and other flu-like symptoms when they received the vaccine at a dose of 250 micrograms. Moderna anticipates the Phase 3 study on dosage will be between 25 and 100 micrograms.

So far, the Moderna study subjects who were vaccinated even at 25 and 100 micrograms achieved antibody levels similar to or even higher than people who naturally became infected with coronavirus.

But it's not clear whether natural infection confers immunity to re-infection, and so similarly it's not clear whether vaccination confers immunity.

"That's a good question, and the truth is, we don't know that yet," Zaks said. "We are going to have to conduct formal efficacy trials where you vaccinate many, many people, and then you monitor them in the ensuing months to make sure they don't get sick."

CNN's Devon Sayers contributed to this report.

Early results from Moderna coronavirus vaccine trial show participants developed antibodies against the virus | CNN

Volunteers who received Moderna's Covid-19 vaccine had positive early results, according to the biotech company, which partnered with the National Institutes of Health to develop the vaccine.

.

Here's where we stand on getting a coronavirus vaccine

By Holly Yan, CNN

Mon June 8, 2020

(CNN) While coronavirus keeps spreading and killing with impunity, the world waits for a vaccine that could quash the pandemic.

But details and timelines keep shifting. Here's the latest on where we stand in the race for a vaccine:

"By the beginning of 2021, we hope to have a couple of hundred million doses," Fauci said.

Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, gave a similar forecast: "If all goes well, maybe as many as 100 million doses by early 2021" would be possible, Collins said.

But many doctors say getting an effective vaccine out by January is a highly ambitious goal.

"Everything will have to go incredibly perfectly if that's going to happen," said Dr. Larry Corey, an expert in virology, immunology and vaccine development.

Why does it take so long to develop a vaccine?

Vaccines have to go through multi-phase trials to make sure they're effective and safe.

Typically, a vaccine takes eight to 10 years to develop, said Dr. Emily Erbelding, an infectious disease expert at the NIAID.

Here's how the process typically works

First, a vaccine is usually tested in animals before humans. If the results are promising, a three-phase trial in humans will begin:

Phase 1: The vaccine is given to a small group of people to assess safety and, sometimes, immune system response. If things go well, researchers move on to:

Phase 2: This phase increases the number of participants -- often into the hundreds -- for a randomized trial. More members of at-risk groups are included. "In Phase II, the clinical study is expanded and vaccine is given to people who have characteristics (such as age and physical health) similar to those for whom the new vaccine is intended," according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If the results are promising, the trial moves to:

Phase 3: This phase tests for efficacy and safety with thousands (or tens of thousands) of people. The substantially larger number of participants in this phase helps researchers learn about possible rare side effects from the vaccine.

What are the dangers of rushing the process?

History has shown that vaccines developed or distributed in a hurry can lead to unintended consequences:

'Operation Warp Speed' is fueling vaccine fears, 2 top experts say

-- In 2017, a rushed campaign to vaccinate about 1 million children for mosquito-borne dengue in the Philippines was stopped for safety reasons. The Philippine government indicted 14 state officials in connection with the deaths of 10 vaccinated children, saying the program was launched "in haste."

-- In 1976, the US was dealing with a novel swine flu outbreak. President Gerald Ford's administration ignored a warning from the World Health Organization and vowed to vaccinate "every man, woman and child in the United States" against the new virus. After 45 million people were vaccinated, researchers discovered a disproportionately high number of them -- about 450 people -- had developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare disorder in which the body's immune system attacks the nerves, leading to paralysis. At least 30 people died.

But overall, vaccines are critical to help preventing disease and death. The WHO estimates vaccines save between 2 million to 3 million lives a year.

So how do we safely speed up the process?

"No vaccine is going to be put forward unless it's been checked out very thoroughly, both in terms of 'Is it safe?' and 'Does it protect you?'" said Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health.

Scientists are trying to find safe ways of speeding up the typical processes. For example:

-- In Seattle and Atlanta, researchers planned to test animals and humans at the same time, instead of animals before humans, according to the health news website Stat.

-- Some vaccines could be mass produced before the trials have even finished. "We're going to start manufacturing doses of the vaccines way before we even know that the vaccine works," Fauci said.

AstraZeneca can now make 2 billion doses of a coronavirus vaccine

If the vaccine trials are successful, millions of doses would be ready to go -- potentially saving lives immediately instead of waiting months for production to ramp up. But if the trials aren't successful, the stockpile of pre-made vaccines could go to waste.

Fauci said one vaccine candidate, made by the biotech company Moderna in partnership with NIAID, should go into a final stage of trials by mid-summer. The plan is to manufacture doses of the vaccine before it is clear whether they work, making close to 100 million doses by November or December, Fauci said.

Scientists should have enough data by November or December to determine if the vaccine works, Fauci said.

Another vaccine candidate, made by AstraZeneca, is underway in the UK and will follow a similar schedule.

Who's making the vaccines?

Dozens of research teams from around the world are working to develop or test coronavirus vaccines. As of early June, there were more than 120 candidate vaccines, the World Health Organization said.

Some are farther along in their trials than others. As of June 4, 10 vaccine candidates were in human trials -- four in the US, five in China, and one in the UK, the WHO said.

"Because we have a number of these (trials), and they all use a different strategy, I am optimistic that at least one, maybe two, maybe three will come through looking like what we need," Collins said.

"We want to hedge our bets by having a number of different approaches, so that it's very likely that at least one of them -- and maybe more -- will work."

Who participates in the trials?

Trial participants are typically volunteers who have not previously been infected with the virus.

Neal Browning, a network engineer in Washington state, said he volunteered because of "the pain that the world is suffering from."

"I can see the deaths. And I feel like anybody else who was in my shoes and close to the research facility and was a healthy person, I hope, would step up and do the same thing for mankind," he said.

Why these volunteers chose to participate in a coronavirus vaccine trial

Why these volunteers chose to participate in a coronavirus vaccine trial

Browning was one of 45 participants in the first phase of Moderna's vaccine trial. He said the 45 participants were broken down into three groups of 15.

One group got a small, 25-microgram dose of the vaccine.

After two weeks, that group showed no major adverse effects from the vaccine. So "the second group -- which got four times that, at 100 micrograms -- was introduced to their dose of the vaccine," Browning said.

After the second group showed no major problems, the third group got 10 times the dosage of the first group -- 250 micrograms.

Browning said he has received two doses of the experimental vaccine and felt "completely normal" afterward.

He said the trial will likely involve a "challenge study, where people will be exposed to the actual virus, so that it's not just academic and we can make sure that ... the vaccine is actually effective."

Browning said he didn't tell his family he was going to volunteer for the study until the last minute, and now they think it's "pretty cool that Dad's doing something like this."

"I think it's important for them to learn that as a member of society, you need to help do whatever you can," he said.

How much would a coronavirus vaccine cost?

This has not been firmly established. The aid group Médecins Sans Frontières -- or Doctors Without Borders -- has urged world leaders to demand pharmaceutical companies sell any successful Covid-19 vaccines at cost price -- that is, without profit.

"Everyone seems to agree that we can't apply business-as-usual principles here, where the highest bidders get to protect their people from this disease first while the rest of the world is left behind," said Kate Elder, MSF senior vaccines policy adviser.

As of early June, governments and philanthropic organizations have given over $4.4 billion to pharmaceutical corporations for the research and development for Covid-19 vaccines, MSF said.

How effective or long-lasting will the vaccine be?

Not all vaccines are created equal. If you get vaccinated against polio, you're probably protected for life. But if you get a flu shot, you might still get the flu that season (though probably with less severe symptoms). And you'll need a different flu shot the next season.

Researchers say at this point, there's no way to predict how effective or long-lasting a novel coronavirus vaccine would be.

But like some vaccines, multiple doses might be needed to get the desired immune response. Collins said the Phase 3 trials will reveal whether one or two injections will be necessary.

Are we sure we'll get an effective Covid-19 vaccine? No. While researchers are optimistic, there's no guarantee.

Coronavirus may not be mutating, but experts say there's still potential for danger

"There are some viruses that we still do not have vaccines against," said Dr. David Nabarro, a professor of global health at Imperial College London.

"We can't make an absolute assumption that a vaccine will appear at all, or if it does appear, whether it will pass all the tests of efficacy and safety."

And if people don't develop long-lasting immunity against the new coronavirus, a vaccine might never work well.

What should we do if we don't get a Covid-19 vaccine?

Nabarro said, "It's absolutely essential that all societies everywhere get themselves into a position where they are able to defend against the coronavirus as a constant threat, and to be able to go about social life and economic activity with the virus in our midst."

CNN's Maggie Fox, Robert Kuznia, Elizabeth Cohen, Jen Christensen, Shelby Lin Erdman and Rob Picheta contributed to this report.

www.cnn.com

www.cnn.com

.

By Holly Yan, CNN

Mon June 8, 2020

(CNN) While coronavirus keeps spreading and killing with impunity, the world waits for a vaccine that could quash the pandemic.

But details and timelines keep shifting. Here's the latest on where we stand in the race for a vaccine:

When will a Covid-19 vaccine be available to the public?

No one's sure yet, but the target is sometime in early 2021.

Vaccines in development around the world are in various stages of testing. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said he's confident one of the vaccine candidates will be proven safe and effective by the by the first quarter of 2021.

But it's not clear which candidate shows the greatest promise yet.

In the meantime, the US government is helping companies such as Moderna ramp up development of their candidate vaccines so that if they're proven to work safely, they can be rolled out quickly.

"By the beginning of 2021, we hope to have a couple of hundred million doses," Fauci said.

Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, gave a similar forecast: "If all goes well, maybe as many as 100 million doses by early 2021" would be possible, Collins said.

But many doctors say getting an effective vaccine out by January is a highly ambitious goal.

"Everything will have to go incredibly perfectly if that's going to happen," said Dr. Larry Corey, an expert in virology, immunology and vaccine development.

Why does it take so long to develop a vaccine?

Vaccines have to go through multi-phase trials to make sure they're effective and safe.

Typically, a vaccine takes eight to 10 years to develop, said Dr. Emily Erbelding, an infectious disease expert at the NIAID.

Here's how the process typically works

First, a vaccine is usually tested in animals before humans. If the results are promising, a three-phase trial in humans will begin: