.

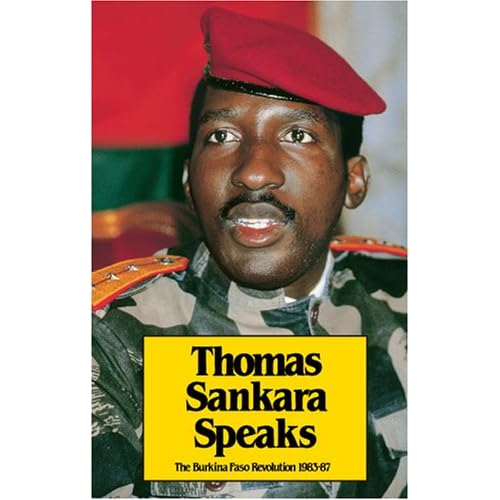

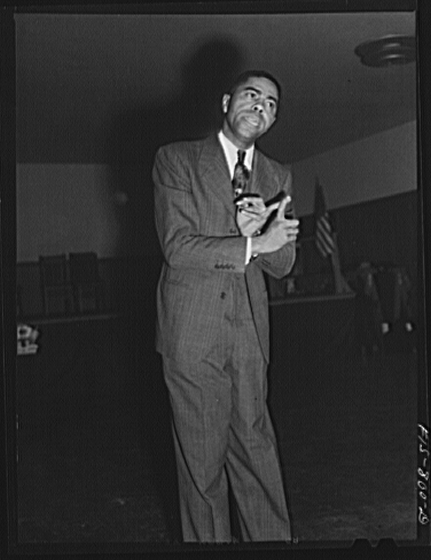

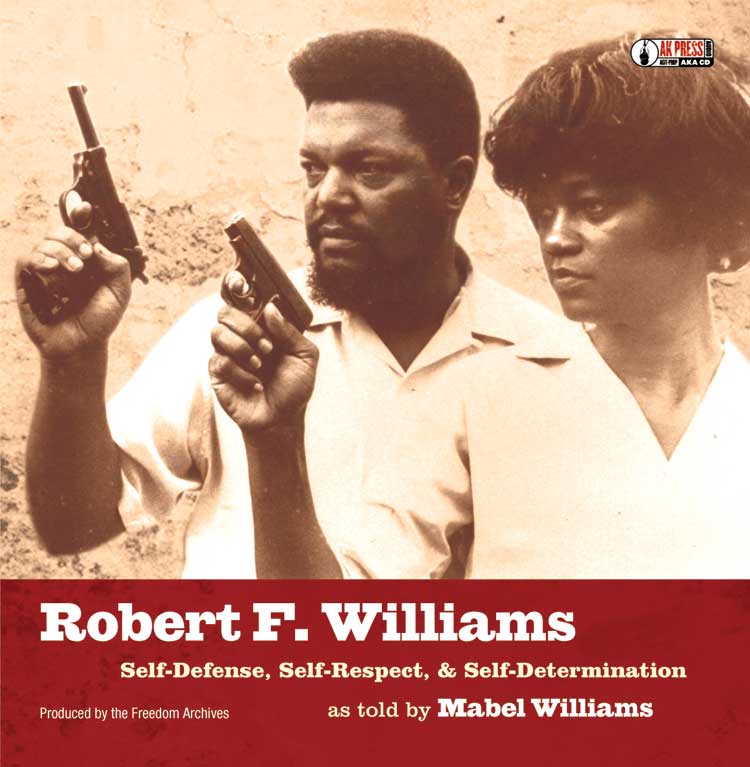

George S. Schuyler

February 25, 1895 - August 31, 1977

Writer, Conservative

source:

The Hoover Institute

LAST YEAR, Random House republished Black No More, a satirical novel by George S. Schuyler (pronounced sky-ler). First published in 1931, the book is a clever story about what would happen if blacks could change their skin color at will. It sends up both race obsessed whites and the leading black figures of the day. All of this is unremarkable — that is, until the reader sees the anonymous biographical note on Schuyler that opens the new edition. We learn that Schuyler was born in Rhode Island in 1895, had parents who "stressed the values of hard work, self-reliance, and determination," and that Schuyler was once "one of this country’s most eminent black journalists." The title of his autobiography: Black and Conservative.

In fact, Schuyler, who died in 1977, was one of the great anti-communists of the twentieth century — it would not be an exaggeration to call him the black Whittaker Chambers (Schuyler, like Chambers, even began his career as a socialist) — as well as a remarkable journalist. In his worldliness and disdain for cant, he was second only to H.L. Mencken, his friend, mentor, and a man who referred to Schuyler as "perhaps the best of all the Aframerican journalists." He was, as one of his old colleagues put it, "a friend to the high priests and the Platos of the streets." Black and Conservative, long out of print, is a classic.

Even in a culture whose media and publishing are dominated by liberal elites, it’s remarkable how completely Schuyler’s name has disappeared from history. A trip to the Library of Congress reveals that he is nowhere to be found in the Contemporary Black Biography, Who’s Who Among African-Americans, or the Dictionary of American Negro Biography. The Internet yields as much information on Schuyler’s daughter Philippa, a child prodigy who would grow up to die tragically in Vietnam. There was only one copy of Black and Conservative in the entire Washington, D.C., public library system. Clerks at several area bookstores had never heard of George Schuyler.

There is, however, a long entry for Schuyler in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. The entry was written by Nickieann Fleener of the University of Utah. Fleener does a fair job summarizing Schuyler’s life. She itemizes Schuyler’s vita: associate editor, columnist, and reporter for the Pittsburgh Courier, once one of the nation’s premier black newspapers, from 1924 to 1966; "one of the first black journalists to gain national prominence in the twentieth century"; and a man who thought of himself as "a citizen of the world as well as a black man." Schuyler "traveled extensively during his career of over fifty years," and "was one of the first black reporters to serve as a foreign correspondent for a major metropolitan newspaper," the New York Evening Post. He was "particularly familiar with social, economic, and political conditions in Africa and Latin America. . . . Because of [Schuyler’s] unique position in the black press, the strength of his satirical style, and the diversity of his subject matter, numerous newspapers and magazines sought his work through the late 1960s. However, Schuyler’s dogmatic conservatism ran in absolute contrast to the philosophies expressed by virtually every major spokesperson of the civil rights movement. As the movement grew, the outlets for Schuyler’s work shrank until he was in virtual obscurity at the time of his death in 1977."

What Fleener doesn’t do, however — what only a reading of Schuyler can do — is give a sense of Schuyler’s writing style. He was called "the black Mencken," and with good cause: He was astringent, authoritative, patrician, funny, and brutally honest in a way that has become impossible for most working journalists today. Schuyler refused, in the most delightful way, to countenance nonsense. Here, from a piece published in the American Mercury in 1939, he tackles blacks’ resistance to the wooing of communists:

Naturally the communists regarded Negroes as sure-fire converts, and have proselyted them these twenty years. They have tried every bait, device, dodge, and argument to win black adherents. Holding interracial dances, defending Negroes afoul of the law, bulldozing landlords, inundating Negroes with "literature," staging countless demonstrations and marches, endorsing Father Divine, nominating black nobodies for office, and courting Negro leaders.

But despite this prodigious activity, the American Negro remains cold to communism. With the communist indictment of traditional mistreatment of black America by white America, he agrees. But he rejects the Muscovite cure. During his three-century struggle to avoid extermination, he has developed certain special techniques of survival, and most communist methods run counter to them. He is suspicious of any program that over-simplifies his problem by ignoring shadings and nuances, and recommends identical tactics in Birmingham and Buffalo.

After a century of listening to black hustlers with Valhallas for sale, the Negro has become wary of schemes for instant salvation. Such movements have habitually attracted only the lunatic fringe, goaded by a handful of disgruntled opportunists. Marcus Garvey, with his incomparable Back-to-Africa set-up, could only corral 30,000 members. More jeers than cheers currently greet the amphigories of Father Divine, and the followers of kindred dark-town messiahs are noisier than they are numerous. Even the Negro clergy no longer wields the old-time influence. . . . In short, the Aframerican is perhaps the most cynical fellow in the Union, and is less likely than the white proletarian to sign a death warrant in a moment of emotional intoxication. True, he only has his life to lose, but he wants to hold on to that.

Schuyler was a tireless worker with an intellect invigorated by books, ideas, and learning. Born in Providence, R.I., then raised in Syracuse, N.Y., his father died when he was three, and his mother remarried a cook and porter for the New York Central Railroad. His mother taught him to read and write before he entered grade school. From the beginning, he was a bookworm. In 1912 Schuyler dropped out of school and joined the army, where he served in Seattle and Hawaii. After his discharge in 1919, Schuyler moved to New York City and then back to Syracuse. There he did part-time odd jobs, which left him time to read. It was around then that Schuyler became interested in socialism. It’s important to emphasize that he was interested — not enamored, bedazzled, or swept off his feet. The biographical notices on Schuyler don’t often make this distinction. Schuyler was an intellect who would travel miles simply to kick around ideas with other intellectuals, and after 1917 the exciting, if insane, ideas that were percolating were socialist ideas.

In 1922 Schuyler returned to New York City. He buried himself in the New York Times, the Nation, the New Republic, and the socialist newspaper the Call, and he soon became involved with the black socialist group Friends of Negro Freedom, led by A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen. Schuyler got a job as an assistant at the Messenger, the journal of the organization. He soon began writing a monthly column, "Shafts and Darts: A Page of Calumny and Satire." His writing caught the eye of Ira F. Lewis, the manager of the Pittsburgh Courier, the black weekly with the second largest circulation in the country. In 1924 Schuyler began to write a column for the Courier for three dollars a week. He would become associate editor and editor of the New York edition of the paper. His association would last until 1966, when the paper unceremoniously disassociated itself with Schuyler following his criticism of Martin Luther King.

While the few accounts of Schuyler’s life note that it was some time in the mid-1920s that he rejected communism, Black and Conservative reveals that Schuyler might have disdained Marxism from the beginning. In it he recalls laughing with putative Bolshevik Philip Randolph about "some Socialist cliche or dubious generalization." Even more skeptical was Chandler Owen, cofounder of the Messenger. Schuyler describes Owen as "a facile and acidulous writer, a man of ready wit and agile tongue endowed with the saving grace of cynicism. He had already seen through and rejected the socialist bilge, and was jeering at the bolshevist twaddle at a time when most intellectuals were speaking of ‘the Soviet experiment’ with reverence. . . . He dubbed the Socialists as frauds who actually cared little more for Negroes than did the then-flourishing Ku Klux Klan."

Schuyler’s work soon caught the attention of H.L. Mencken, who would become his lifelong friend and correspondent. The journalist of their kind is now extinct — the polemicist (not pundit) who had not gone to an Ivy League school (indeed, who had avoided higher education entirely) and who was also a working journalist with a great gift for telling a story. Mencken and Schuyler were great debunkers. They were also not afraid of the nuts and bolts of good journalism. Indeed, to simply regard Schuyler as a combustive editorial writer does serious disservice to his vast body of work and experience. Some of the best parts of Black and Conservative are accounts of Schuyler’s time living with a group of bums in the Bowery in New York City and of his labors at odd jobs to get by.

Like Mencken, Schuyler also traveled to the South and wrote about it as an outsider. In 1925, the Courier sent him on a tour to boost readership below the Mason-Dixon line and report on conditions of blacks in the South. "Next to being strictly honest," he wrote in the American Mercury, "there is no more trying state in this humdrum republic than being simultaneously a Negro and a traveler." In Black and Conservative he recalls that he traveled by bus from town to town in the Jim Crow South, armed only with the barest statistics about the place — population, transportation facilities, sources of employment. He soon developed a routine he would use on assignment for the New York Post in Liberia, Latin America, and Europe. He would first interview a cab driver who would take him on a tour of the town, then talk to a local barber, bellboy, landlord, and policeman. The next day he would interview town officials. It’s the kind of shoe leather journalism rarely practiced anymore.

In 1926, Schuyler became the chief editorial writer for the Courier. That same year the Nation published his article, "The New Negro Art Hokum." In it, Schuyler dismembered the movement, then at its apex, known as the "Harlem Renaissance." Supporters of the movement claimed that the explosion of art, from paintings to literature to jazz, represented a new and distinctly black form of aesthetic expression. Hooey, wrote Schuyler.

As for the literature, painting, and sculpture of Aframericans — such as there is — it is identical in kind with the literature, painting, and sculpture of white Americans — that is, it shows more or less evidence of European influence. In the field of drama little of any merit has been written by and about Negroes that could not have been written by whites. The dean of Aframerican literature is W.E.B DuBois, a product of Harvard and German universities; the foremost Aframerican sculptor is Meta Warrick Fuller, a graduate of leading American art schools and former student of Rodin; while the most noted Aframerican painter, Henry Ossawa Tanner, is dean of American painters in Paris and has been decorated by the French Government. Now the work of these artists is no more "expressive of the Negro soul" — as the gushers put it — than are the scribblings of Octavus Cohen or Hugh Wiley.

This, of course, is easily understood if one stops to realize that the Aframerican is merely a lampblacked Anglo-Saxon. If the European immigrant after two or three generations of exposure to our schools, politics, advertising, moral crusades, and restaurants becomes indistinguishable from the mass of Americans of the older stock (despite the influence of the foreign-language press), how much truer must it be of those sons of Ham who have been subjected to what the uplifters call Americanism for the last three hundred years. Aside from his color, which ranges from very dark brown to pink, your American Negro is just plain American. Negroes and whites from the same localities in this country talk, think, and act about the same. Because a few writers with a paucity of themes have seized upon imbecilities of the Negro rustics and clowns and palmed them off as authentic and characteristic Aframerican behavior, the common notion that the black American is so "different" from his white neighbor has gained wide currency.

What is remarkable about this passage is not only its candor and vitality, but the fact that it appeared in the Nation, a left-wing magazine (which did, however, publish a response from the poet Langston Hughes the next week). To be sure, Schuyler got his share of hate mail; some of the funniest parts of Black and Conservative are his responses to left wingers demanding that he be fired. But until the late 1960s, his career was never in jeopardy. He seemed to have come from an era when mainstream newspaper and magazine editors were made of sterner, less pusillanimous and politically correct stuff.

In fact, Schuyler was even rewarded by the black community for his talent; from 1937 to 1944 he was the business manger of the NAACP, an organization whose left-leaning ways he never hesitated to criticize. Black and Conservative shocks and delights on page after page not only as a fascinating story told by a master stylist, but as an example of a journalist working with genuine and absolute freedom of expression. Not freedom of expression as understood by the modern newspaper world, but real freedom — the ability to denounce, with genuine verve, intensity, and hostility, ideas that one sees as bunk. So much of modern editorial writing has become what the Wall Street Journal recently called it — cardboard. Schuyler was a dynamic mural. After a trip to Liberia, he flatly announced that the African country was not ready for self-rule. When the black leader W.E.B. DuBois became editor of the communist magazine the New Masses in 1946, Schuyler squared off: "Agitation is the food and fuel of Communists and all of its organs of propaganda. So when Dr. DuBois joins the New Masses he is more definitely than ever committed to that policy. . . . After all, perhaps it is appropriate that DuBois should join Stalin’s literary gendarme where inconsistency, backbiting, and charlatanism are crowning virtues and political irregularity is the only vice." Imagine such an item running in a newspaper today.

Indeed, it’s hard to read much Schuyler and not be awed by the fierce clarity and wisdom — of a kind often absent from dialogue about race today. In 1950 Schuyler was a delegate to the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an anti-communist group (that, as Schuyler explains, had more than a few communists in it). His address, "The Negro Question Without Propaganda," is a masterpiece of perspicacity and pure level-headedness. "Actually," Schuyler wrote, "the progressive improvement of interracial relations in the United States is the most flattering of the many examples of the superiority of the free American civilization over the soul-shackling reactionism of totalitarian regimes. It is this capacity for change and adjustment inherent in the system of individual initiative and decentralized authority to which we must attribute the unprecedented economic, social, and educational progress of the Negroes in the United States." The piece was distributed to every U.S. embassy and entered into the Congressional Record. Schuyler rewrote the piece as "The Phantom American Negro," emphasizing in the new draft that the media were presenting the American public with of blacks as perpetually aggrieved, angry, rebellious, and revolutionary. This picture, claimed Schuyler, was simply false. It was reprinted by 17 magazines the world over, including Reader’s Digest.

Black and Conservative is also a tragedy, not because of what is in it, but because of what happened just a year after its 1966 publication. In 1928 Schuyler married Josephine E. Lewis, the white daughter of a prominent Texas family. In 1932 they had a daughter, Philippa, who became Schuyler’s deepest source of joy. Philippa Schuyler was a child prodigy. Her iq was 185, and she could read and write at two and a half. At three she could play the piano, and at four she was composing classical music. She performed on the radio at age five, and at 13 wrote a piece of music, "Manhattan Nocturne," that she performed with the New York Philharmonic. At the 1944 New York World’s Fair, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia declared June 19 "Philippa Duke Schuyler Day." She would write several books and win 27 music awards. She was profiled by Joseph Mitchell in the New Yorker. Mitchell was taken with Philippa, but referred dismissively to her father as the author of "a rather angry column for the Pittsburgh Courier." Philippa was also a great beauty. According to the Washington Post, "for hundreds, thousands of black kids in the 40s and 50s, she was a role model, a reason to take piano lessons."

She would also die young. In the mid-1960s, Philippa had grown tired of touring to play classical concerts and decided to follow in her father’s footsteps. It was 1964 and by then the civil rights movements had begun to become entangled with the militant black power movement. That year Schuyler was dumped from the Courier for his opposition to Martin Luther King receiving the Nobel Peace Prize (an opposition that was wrong, in my view, because of its refusal to differentiate between King’s nonviolent crusade and the combative black power movement). Schuyler spent the last years of his career writing columns for the Manchester Union Leader and film reviews for the John Birch weekly Review of the News.

Philippa traveled to Vietnam as a correspondent for the Union Leader. She would also play a few concert dates. On May 9, 1967, she was killed in a helicopter crash while trying to transfer Catholic schoolchildren to safety. She was 35. Schuyler must have been devastated, although he didn’t show it. Union Leader publisher William Loeb described Schuyler at the funeral as "a composed man. Whatever he felt inside he knew that a gentleman doesn’t bare [his feelings] to the rest of the world." How tragic that a man who dedicated his entire life to fighting communism would lose his only daughter to ts scourge. His wife died two years later.

George Schuyler died in 1977. As the liberal black writer Ishmael Reed notes in his introduction to Black No More, in the last few years of Schuyler’s life it was considered offensive in black circles even to interview the old newspaperman. Yet history has turned out differently than Schuyler’s adversaries thought. The West won the Cold War, and people seem increasingly capable of coming around to the truth that communism was one of the great unambiguous evils of our century — that in their evil hearts there was no difference between fascism, Nazism, and communism. This is what Schuyler wrote in 1937:

What seems to have escaped the generality of writers and commentators is that all three forms of government are identical in having regimented life from top to bottom, in having ruthlessly suppressed freedom of speech, assembly, press and thought, and in being controlled by politicians. . . . What is new about these forms of government is that they are controlled by politicians with a reformer complex; ex-revolutionists who have gained power and have nobody to curb their excesses. . . . The politicians, being the only class in society that is charlatan enough to offer a cure for everything, are quick to see the opportunity. They promise the suffering people everything if elected to office, as Lenin promised, as Mussolini promised, as Hitler promised and as our Big Boss promised.

Order requires regulation, regulation requires regimentation, regimentation is based on a plan, nothing must interfere with the operation of the plan if it is to be successful; criticism of the plan might conceivably hinder operation and must therefore be squelched.

We are rapidly approaching this form of State in this country and practically have it in all but name. It won’t be long now.

Maybe it will take a while yet — at least while the writings of George Schuyler remain available, even if only in the dark recesses of the last library in town.

source:

http://web.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap9/schuyler.html

PAL: Perspectives in American Literature - A Research and Reference Guide - An Ongoing Project

© Paul P. Reuben

(To send an email, please click on my name above.)

Chapter 9: George Samuel Schuyler (1895-1977)

Outside Links: | GSS Papers | Heath Anthology Introduction |

Page Links: | Primary Works | A Brief Chronology | Selected Bibliography 10980-Present | MLA Style Citation of this Web Page |

| A Brief Biography |

Site Links: | Chap. 9: Index | Alphabetical List | Table Of Contents | Home Page | April 6, 2007 |

Primary Works

"Negro-Art Hokum." The Nation, June 16, 1926.

Racial Intermarriage in the United States: One of the Most Interesting Phenomena in Our National Life. According to my research so far, it was first published as an article in The American Parade in 1928, then (c. 1929) as a Little Blue Book, some time before his Black No More. (contributed by Virginia Berger, May 17, 2003)

Slaves Today: A Story of Liberia, 1930

Black no more: a novel (1931). New York: Modern Library, 1999. PS3537 .C76 B56

Black Empire, An Imaginative Story of a Great New Civilization in Modern Africa, 1937-38

Fifty Years of Progress in Negro Journalism, 1950.

Black and Conservative (autobiography), 1966.

"The Reds and I." American Opinion, March 1968.

"The Negro-Art Hokum." Within the Circle: An Anthology of African American Literary Criticism from the Harlem Renaissance to the Present. Ed. Angelyn Mitchell. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1994. 51-54.

"Phylon Profile, XXII: Carl Van Vechten." Remembering the Harlem Renaissance. Ed. Cary D. Wintz. NY: Garland, 1996. 154-60.

| Top |Chronology of Schuyler's Work (from Michael W. Peplow)

1926 "The Negro-Art Hokum" in The Nation and "Seldom Seen" in The Messenger

1927 "Blessed are the Sons of Ham" in The Nation, March 23; "Our White Folks" in The American Mercury, December; and "Our Greatest Gift to America" in Ebony and Topaz: a Collectanea, ed. Charles S. Johnson, (New York: Opportunity; National Urban League, 1927), 122-24.

1928 "Woof" in Harlem, November; "Racial Intermarriage in the United States" in The American Parade, Fall

1929 "Keeping the Negro in His Place" in The American Mercury, August; "Emancipated Woman and the Negro" in The Modern Quarterly, Fall

1930 "A Negro Looks Ahead" in The American Mercury, February; "Traveling Jim Crow" in The American Mercury and Reader's Digest; "Black Warriors" in The American Mercury, November and in Slaves Today: A Story of Liberia

1931 Black No More, his novel, is published.

1932 "Black Art" and "Black America Begins to Doubt" in The American Mercury

1934 "When Black Weds White" in The Modern Monthly and Die Auslese

1937 Black Empire, An Imaginative Story of a Great New Civilization in Modern Africa is published

1944 "The Caucasian Problem" in What the Negro Wants, Rayford Logan, ed. U of North Carolina, 1944

1951 "The Phantom American Negro" in The Freeman, April 23

1956 "Do Negroes Want to be White?" in The American Mercury, June 1956

1959 "Krushchev's African Foothold" in The American Mercury

1966 Black and Conservative, his autobiography, is published.

1968 "The Reds and I." American Opinion, March 1968.

1973 "Malcolm X: Better to Memorialize Benedict Arnold" in American Opinion, February 1973

Selected Bibliography 1980-Present

Ferguson, Jeffrey B. The Sage of Sugar Hill: George S. Schuyler and the Harlem Renaissance. New Haven: Yale UP, 2005.

Leak, Jeffrey B. ed. Rac[e]ing to the Right: Selected Essays of George S. Schuyler. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P 2001.

Peplow, Michael W. George S. Schuyler. Boston: Twayne, 1980. PS3537.C76 Z83

| Top |George Schuyler (1895-1977): A Brief Literary Biography

A Student Project by Leslie Mefford

He wrote the first full length satire by a black American; he was one of the most distinguished, productive and controversial black newspapermen; he was a muckraking journalist, international correspondent, a critic and book reviewer; he was George S. Schuyler, and his accomplishments are very impressive (Peplow, 9). However, even with all of his endeavors, Schuyler has almost vanished from history. He is missing from the Contemporary Black Biography, Who's Who Among African-Americans, and the Dictionary of American Negro Biography. There is only one copy of his autobiography, Black and Conservative, in all of Washington D.C.'s public libraries, and numerous bookstore have never even heard of George S. Schuyler (Judge, policy). It is remarkable how a man that carries so many fascinating life achievements seems to have never existed; but he did.

George S. Schuyler was born on February 25, 1895 in Rhode Island. He grew up in Syracuse, New York with his parents who taught him self-discipline, independence , thrift and industry (Peplow, 18). Schuyler was quick to learn and knew how to read and write before he began school. At a young age he was a booklover; he "was a tireless worker with an intellect invigorated by books, ideas and learning" (policy). His father died when Schuyler was about three, but his mother remarried. He attended school in Syracuse until 1912 when he joined the army at age seventeen. Schuyler was assigned to the segregated Twenty-fifth U.S. Infantry Regiment stationed in Seattle (Reed, introduction, Black No More). He stayed with the army for seven years, and it is during these years that he developed his journalism skills. He would later write of his army days in "Woof," "Black Warriors" and Black and Conservative (19). He came back to New York and was involved with the black socialist group Friends of Negro Freedom (v).

Schuyler married Josephine E. (Lewis) Cogdell in 1928. Lewis was a wealthy white woman who came from a distinguished family in Texas. The Schuyler family had one child -- a daughter named Philippa. She was a child prodigy with an IQ of 158. She could read and write at the age of two and a half, and by the time she was four she was composing classical music for piano, which she had played since she was three (policy). Philippa died in 1967, and her death devastated Schuyler. It is ironic that she died in Vietnam during the war since Schuyler completely disagreed with communist ideas and committed his life to fighting it. She was killed in a helicopter accident while she was transporting Catholic children to safety (policy). Schuyler's wife died shortly after in 1969.

A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, who also led the socialist group Friends of Negro Freedom, claim to have revealed Schuyler to the world with their publication The Messenger (Peplow,21), which Schuyler work for five years. Schuyler was gaining a reputation; and his work caught the attention of Ira F. Lewis -- the manager of the Pittsburgh Courier had a job with that paper until 1966 (policy); Schuyler worked in publication almost his entire life. With his name out in the public eye, Schuyler decided to become part of the Harlem Renaissance and began publishing work "supporting the new 'radical' ideas of immediate manhood rights, equal consideration before the law, and an end to lynchings, Jim Crow, and second class citizenship (21). He was known as an iconoclast which is someone who degrades anything others may hold as sacred or condemns respected values or societies; satire came second nature to Schuyler, and he made a good living at it. Schuyler makes this statement about his work, and why he writes: "Whatever I think is wrong, I shall continue to attack. Whatever is right, I shall continue to laud....I have always been more concerned with being true to myself than to any group....I shall continue to pursue this somewhat lonely and iconoclastic course". Black organizations were not happy with Schuyler's attitude and often called him an Uncle Tom. He infuriated enough people to let everything he had done in his life be forgotten: his work, contributions of satire in literature, his journalism, everything, and perhaps this is why finding out about him is so difficult; nobody cared to hear him anymore.

| Top | Schuyler's work grabbed the interest of H. L. Mencken who worked as a "lampooning social critic" for American Mercury (Reed, vi) and would later be Schuyler's mentor. Schuyler was called "the black Mencken;" he was harsh, convincing, posh, amusing, and brutally honest. Mencken would publish several of Schuyler's works in American Mercury. The two became life-long friends; "they were not afraid of the nuts and bolts of good journalism" (policy). Mencken referred to his friend as "'perhaps the best of all the Aframerican journalists'" (policy). Mencken was not the only one to find Schuyler's writing appealing; W. E. B. Du Bois found the "thinly disguised caricatures of black leaders" (including himself) amusing in Schuyler's novel Black No More a book that established a "mythical solution to the race problem" (Reed, vi). Black No More was published in 1931.

Schuyler had become completely conservative by the 1960s and started to publish his controversial works like "The Reds and I" in American Opinion which was a publication put out by the John Birch Society. During this time Schuyler was attacked by The Crisis for statements he made criticizing Martin Luther King. He also was nominated, at this time, to run against Adam Clayton Powell in the 1964 Congressional elections, although unsuccessful (vi).

Schuyler did not completely aggravate everyone, and in fact, he pleased the black community with his talent; from 1937 to 1944 he was the business manager of the NAACP, which he never hesitated to criticize (policy).

The man had a lot to say and had a style all his own. He wrote about his life in his autobiography Black and Conservative which was published in 1966. Schuyler had strong beliefs and he dedicated his life to those beliefs. William Loeb states: "'My impression of George is one of a greatly balanced individual whose judgment and dedication and devotion to principle is so strong that he has no intention of being swayed by praise or criticism. An iconoclast. Lonely, perhaps, but a man we should listen to'" (Peplow, 30). "John Henrik Clarke perhaps best explained Schuyler's life when he observed: 'I used to tell people that George got up in the morning, waited to see which way the world was turning, then struck out in the opposite direction. He was a rebel who enjoyed playing that role'" (Reed, vii). George Schuyler died in New York in 1977.

| Top | Chronology (from Michael W. Peplow)

1895 George S. Schuyler is born on February 25

1912 Served in the army until 1919

1923 Assistant editor for The Messenger until 1928

1924 Worked for Pittsburgh Courier until 1966

1928 Married Josephine (Lewis) Cogdell (name varied in research)

1930 Began Young Negroes' Cooperative League

1932 Edited The National News

1934 Special publicity assistant to NAACP until 1935

1937 Became business manager for The Crisis

1943 Associate editor of The African

1960 Interviewed for Oral History Collection at Columbia University

1961 Joined the John Birch Society

1964 Nominated to run against Adam Clayton Powell

1965 Was attacked editorially in The Crisis

1966 Stopped writing for Pittsburgh Courier

1968 Received American Legion Award

1969 Received Citation from Catholic War Veterans and in May his wife died

1972 Received Freedoms Foundation Award

1977 George S. Schuyler died on August 31

Works Cited

Judge, Mark Gauvreau. "Justice to George S. Schuyler." Policy Review, April 5, 2001.

http://www.policyreview.com/aug00/Judge_print.html

Lewis, David Levering, ed. The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader. New York: Penguin Books, 1994. 654.

Peplow, Michael W. George S. Schuyler. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980. Whole book used.

Schuyler, George S. Black No More. New York: The Modern Library, 1999. v-xiii.

MLA Style Citation of this Web Page

Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 9: George Schuyler." PAL: Perspectives in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide. URL:

http://web.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap9/schuyler.html (provide page date or date of your login).

Further reading at George Samuel Schuyler on Wikipedia